“Welcome Poets” provides a portal into the Wisconsin places that shaped Lorine Niedecker’s identity

A meditation on the 20th-century Wisconsin poet’s artistic impact, in relation to Poet Laureate Nicholas Gulig’s own six-part series that screens at Art Lit Lab on October 18.

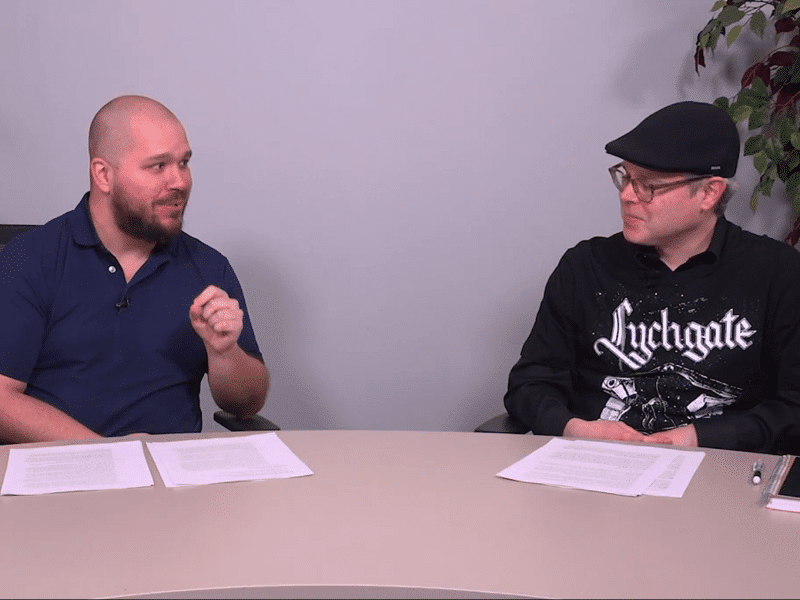

A new PBS Wisconsin six-part documentary series, Welcome Poets, is bringing renewed attention to one of Wisconsin’s most distinctive literary voices of the 20th century, poet Lorine Niedecker. These episodes of approximately 10 minutes each, and totaling one hour, will screen on Saturday, October 18, at 7 p.m. at Arts + Literature Laboratory with producer Colin Crowley and 2023-2024 Wisconsin Poet Laureate Nicholas Gulig in attendance.

The series follows Gulig as he shares how Niedecker’s minimalist style and attention to place shaped his own writing and identity. Episodes collectively convey how both poets, through their work and experiences, contributed to Wisconsin’s literary heritage, while emphasizing the city of Fort Atkinson as a source of poetic inspiration.

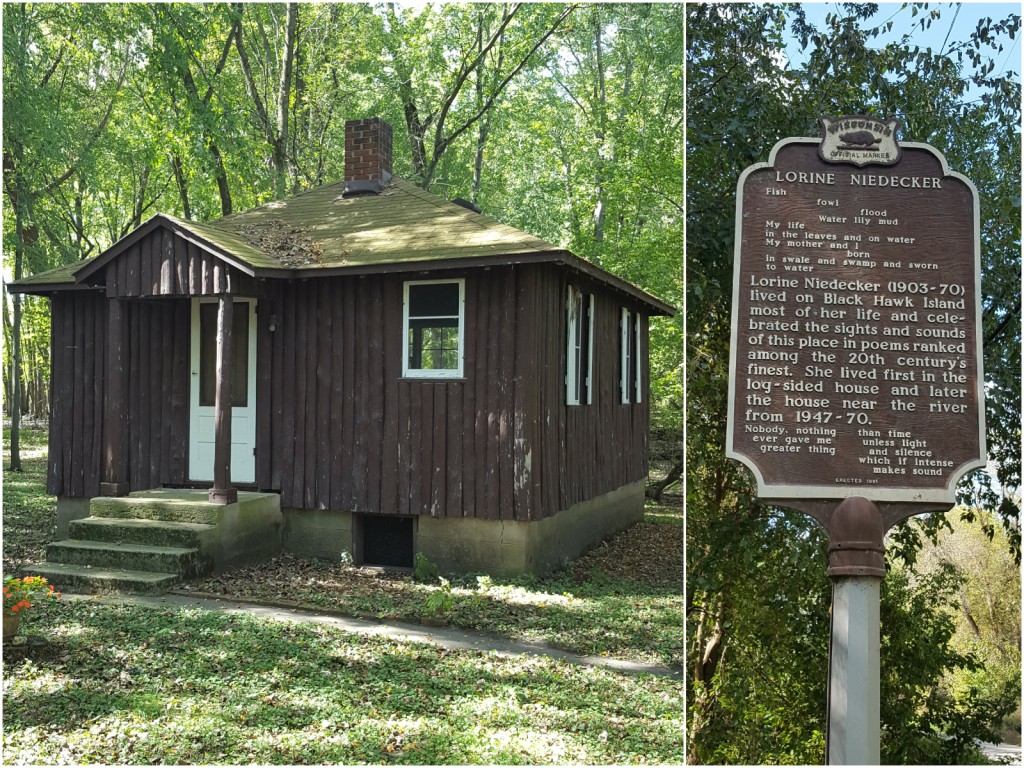

When I first learned about Welcome Poets, I felt an immediate kinship with Gulig’s quest. Like him, I grew up in a small river town in Wisconsin and was drawn to writing and poetry from a young age. Discovering Lorine Niedecker’s work set me on my own poet’s pilgrimage to Fort Atkinson to better understand her life and writing.

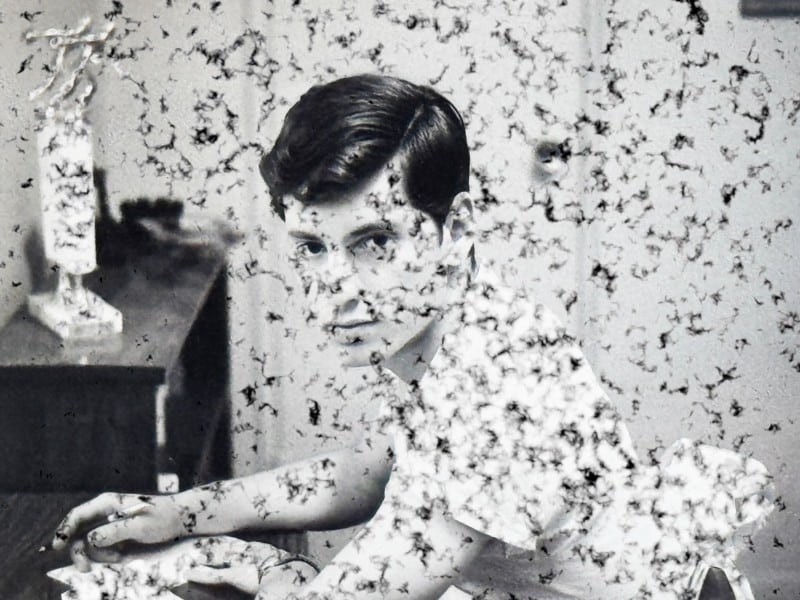

I didn’t actually encounter Niedecker’s poetry until adulthood, and I was stunned that such a powerful, original voice had escaped my attention. I was drawn to her work for the intensity of her observations and her ability to convey so much with so few words. Her autobiographical poem, Paean To Place, uses minimal, carefully spaced lines to evoke a flow of memory and landscape. Niedecker allows silence and simplicity to carry the emotional weight of her reflections and experiences.

Niedecker was also a deeply fascinating person: a reclusive woman who spent most of her life in relative poverty, working modest jobs while quietly producing some of the most precise, emotive poetry of the century. Even as a literature student at UW–Platteville, where I took a modern poetry class as an elective, Niedecker’s name never appeared during my studies. Here was someone often called “the Emily Dickinson of the 20th century,” writing in my own state, and I had never learned about her.

Much of Niedecker’s poetry was familiar and highly relatable. Her work felt like another voice from a world I knew: quiet, rural, shaped by water and economic precarity. My childhood home in Prairie du Chien sat near the Mississippi River, and seasonal flooding was a regular reminder of the power of water: beautiful, life-giving, uncontrollable, destructive.

Both our towns were defined by 19th-century U.S. military forts (Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien and Fort Koshkonong near Fort Atkinson) that played a role in displacing Wisconsin’s Indigenous tribes. Both communities remember Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak), the Sauk chief who resisted the theft of his people’s lands, and so we each grew up—albeit separated by several decades—surrounded by reminders of colonialism and its lasting impact. In her poetry, Niedecker wrote about Black Hawk and explored questions of land: its ownership, its loss, and the ways we can belong to and be shaped by it. These were questions I returned to repeatedly in my own thinking about place and identity.

As I read more of Niedecker’s work, my fascination deepened. I began referencing her in my own writing, experimenting with how much meaning could exist in the fewest possible words. In her poem Poet’s Work, she writes: “Grandfather advised me: Learn a trade / I learned to sit at desk and condense / No layoff from this condensery.“ The poem reflects her dedication to writing and editing as both labor and vocation, and it is one I have often remembered in my own work.

Another line from one of her untitled poems, “What would they say if they knew I sit for two months on six lines of poetry?” reveals something more intimate and vulnerable: the quiet uncertainty that can accompany creative endeavors. That tension between persistence and self-doubt is a feeling many artists recognize (including myself).

Between 2017 and 2019, I attended poetry festivals and workshops celebrating Niedecker. During these trips, I explored Fort Atkinson, and discovered the places that inspired her writing. At the Hoard Historical Museum, a room devoted to Niedecker displayed several of her watercolor paintings, offering another window into her world.

A few blocks away, at the Dwight Foster Public Library, I spent time in the Niedecker Room, perusing her personal library (what she called her “Immortal Cupboard”), which had been donated after her death in 1970. (In 2024, remaining books in Niedecker’s library were moved, and they are now housed at the Hoard Historical Museum.) I noted titles such as George Orwell’s 1984 and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court, which I also keep on my bookshelf. I also noticed her interest in politics and philosophy, with works by Robert La Follette, Erich Fromm, Marcus Aurelius, and David Hume. And of course, there was poetry: classics by Emily Dickinson, Sappho, and Walt Whitman, as well as from contemporaries like Louis Zukofsky and Cid Corman.

What struck me most, though, was how many of her books consisted of collections of letters. Niedecker’s library features books that contain the correspondence of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Franz Kafka, Sigmund Freud, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Lord Byron, among others. To me, this suggests that Niedecker was drawn not only to the finished works of writers and thinkers, but to the raw, private exchanges that revealed their personal lives and inner worlds.

So many of Niedecker’s interests were similar to my own. Some of the same writers who helped shape my thinking had also shaped hers, and in that overlap, I felt a connection. Looking through her library made her seem less like a distant literary figure and more like a kindred spirit, navigating similar questions about art, politics, and the human condition.

Watching Gulig’s journey in Welcome Poets brought my own experiences full circle. His reflections on Niedecker’s attention to place echoed what had drawn me to her work. Her poetry taught me the importance of observing the world around us and how the landscapes we inhabit, and our perceptions of them, can shape both voice and identity.

Welcome Poets shows the ways in which Niedecker’s influence continues to ripple outward, carried by writers who find that her work reflects some of their own creative questions. Discovering Lorine Niedecker was more than uncovering the legacy of a local poet; it was encountering a voice that echoed my own search for belonging, language, and expression. Her words, and projects like Welcome Poets, remind us that art endures in the landscapes that shape us, and that even the quietest voices can persist across time.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.