“The Elephant Man” imbues a transcendent portrait of a tortured outsider with deep compassion

David Lynch’s haunting sophomore feature kicks off the summer season at UW Cinematheque on June 25.

David Lynch’s haunting sophomore feature kicks off the summer season at UW Cinematheque on June 25.

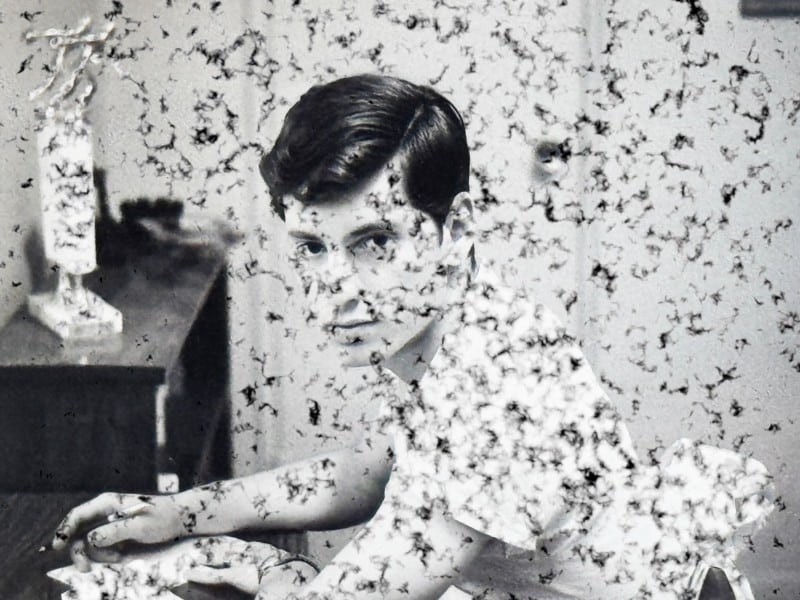

“Life!… is full of surprises.” David Lynch had only made one feature—the deliriously radical cult sensation Eraserhead (1977)—when he received his first Hollywood assignment. Though the film established Lynch as a significant new voice in independent cinema, not many people had actually seen it at the time. Eraserhead found a home as a midnight movie in New York City, which allowed it to attract a small group of devotees (as well as the attention of auteur filmmakers as diverse as John Waters and Stanley Kubrick). Compared to Lynch’s directorial debut, The Elephant Man (1980) proved to be a project on an entirely new level.

With this haunting, heartwarming, humanist horror movie set in Victorian London, Lynch made the leap from obscurantist experimental microbudget filmmaking to mainstream commercial cinema—without compromising the power of his singular artistic vision. Despite its classical linear narrative and elegant formality, The Elephant Man clearly prefigures the populist surrealism that would come to define Lynch’s oeuvre in the ’80s and ’90s.

The Elephant Man tells the real-life story of Joseph Merrick (named “John” in the film, played by John Hurt), who suffered from a rare genetic condition called neurofibromatosis, causing tumorous growths in his bones and leaving him grotesquely deformed. Merrick eked out a living exhibiting his body in an itinerant freak show until he was rescued by Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins), a London surgeon who provided a tranquil residence for him and introduced him to high society.

UW Cinematheque kicks off its summer series on Wednesday, June 25, at 7 p.m., with a new 4K DCP restoration of Lynch’s second feature. In tribute to the well-beloved American cultural icon who passed away in January of this year, in July, the Cinematheque will also present a program of Lynch’s short films and a 35mm print of Mulholland Dr. (2001). These latter two screenings will be followed by in-person discussions with Mary Sweeney, who has a long history of creative collaborations with Lynch. Sweeney visited 4070 Vilas Hall three years ago to introduce his idiosyncratic biographical road movie The Straight Story (1999), which she produced, edited, and co-wrote. (Among other topics, she talked about Lynch’s connections to Madison.)

How did it happen that an unknown 33-year-old American avant-garde filmmaker found himself in London, surrounded by the crème de la crème of British actors, directing a prestige picture? In his 2018 memoir Room To Dream, Lynch recounts the origins of his involvement with The Elephant Man. He asked producer Stuart Cornfeld if there were any screenplays that he could possibly direct. They met at a coffee shop in Beverly Hills, and Cornfeld told Lynch that he had four potential scripts. “The first one is called The Elephant Man,” he said. Lynch recalls that it was as though “a hydrogen bomb went off in my brain.” Although he had never heard of Merrick, Lynch responded to the title alone and knew right then and there that he was going to do the film. (He never did find out what those other three scripts were.)

As Lynch read the script, he became captivated by Merrick’s story. About why he was drawn to the subject, he said: “Loving textures to start off with, and this idea of going beneath the surface was intriguing to me. There is the surface of this elephant man, and beneath the surface is this beautiful soul.” In an interview from the 2005 edition of filmmaker and writer Chris Rodley’s book Lynch On Lynch, the artist elaborates on his fascination with Merrick and describes the papillomatous growths on his body as “slow explosions.”

While The Elephant Man might now seem like an outlier in Lynch’s career, it bears the stamp of his essence. Lynch imbues his striking, transcendent portrait of Merrick with deep compassion and a keen sense of the duality of human nature, while masterfully evoking the atmosphere of London in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution. The incredible, almost mythical tale of the so-called “Elephant Man” provided abundant raw material for the artist to refine his distinctive cinematic style. Throughout his filmography, Lynch penetrated the surface of reality to explore the absurd mystery of the strange forces of existence.

“Human beings are like little factories,” Lynch states in Lynch On Lynch. “They turn out so many little products. The idea of something growing inside, and all these fluids and timings and changes, and all these chemicals somehow capturing life, and coming out and splitting off and turning into another thing . . . it’s unbelievable.”

As The Elephant Man unfolds, the mood shifts between the clinical clarity of daytime and the distorted, carnivalesque realm of nocturnal horrors. The mix of research, location, and Lynch’s fevered imagination creates an image of 19th-century London that is eerily reminiscent of the dystopian industrial hellscape in Eraserhead. (Richard Brody of The New Yorker described it as “history on the edge of the unconscious.”) Against this stark, otherworldly urban backdrop, Merrick seems to embody the spiritual disfigurement of the era. (And no, I will not elaborate on that.)

A timeless work of dark beauty, The Elephant Man stands out as Lynch’s most conventional, collaborative, and history-based film, as well as his greatest commercial and artistic success. It was nominated for eight Academy Awards and brought the director an exponential increase in public and critical recognition. In bringing this poignant tale of the ultimate tortured artist to vivid life on the big screen, Lynch—another kind of romantic outsider—revealed his beautiful soul to the world.

Editor’s note: In the film, the real-life Joseph Merrick is named John Merrick. The image caption and review have been updated to reflect that fact. This is related to Frederick Treves mistakenly listing Merrick’s name as “John” rather than “Joseph” in his 1923 book The Elephant Man And Other Reminiscences.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.