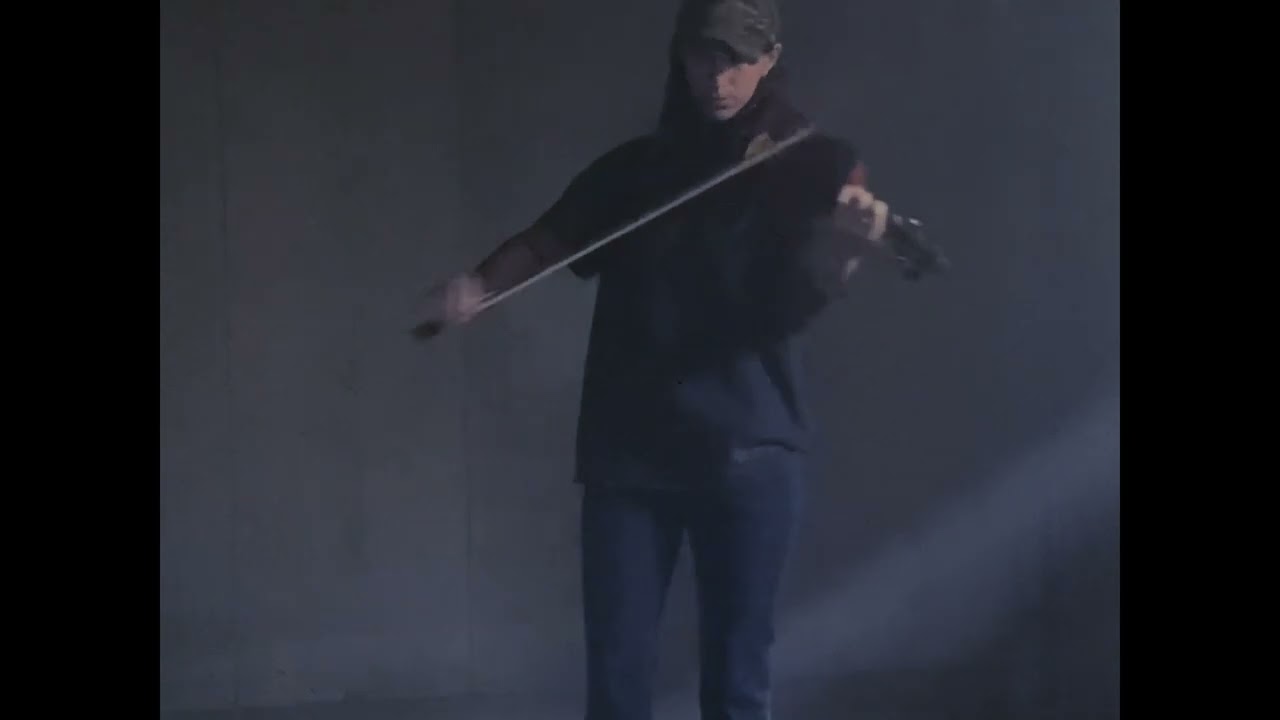

Elori Saxl’s “Drifts And Surfaces” excels in economical arrangement

The New York-based ambient artist talks with us about the artistic potency of Madeline Island.

The New York-based ambient artist talks with us about the artistic potency of Madeline Island.

An electronic pulse rings out, accentuated by an ethereal synth drone that evokes the presence of wind. The effect is mesmeric and chilling. Tonally icy and gently desolate in overall feeling, the first few seconds of New York-based ambient artist Elori Saxl’s latest album, Drifts And Surfaces, create a vivid impression. Saxl’s 2021 debut, The Blue Of Distance, incorporated field recordings of the environment of Madeline Island, the largest of northern Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands group in Lake Superior. This time around, Saxl doesn’t use field recordings but has nonetheless managed to create an album that feels more spiritually reflective of the Bayfield Peninsula and its island neighbors at Wisconsin’s northernmost tip. Those locations inhabit Saxl’s work, which continues to pay particularly close attention to the lake.

Drifts And Surfaces is made up of three distinct pieces, each springing from a different commission: “Drifts I,” “Drifts II,” and “Surfaces.” “Drifts I” was commissioned by Third Coast Percussion of Chicago, “Drifts II” was commissioned by the Brooklyn-based trio Tigue, and “Surfaces” was commissioned by the Guggenheim for a retrospective on the eight-decade career of American painter Alex Katz. Ultimately, Saxl saw each of these works as spiritual relatives, despite their distinct underlying origins. The instinct was dead-on. Drifts And Surfaces, whether intentional or not, forms a formidable whole.

“Drifts I” effectively establishes Drifts And Surfaces‘ wintry aesthetic, which Saxl sustains for the duration of the release’s 24-minute runtime. Every second of the album teems with an inescapably lived-in sense of isolation, further buoyed by Saxl’s compositional prowess. Drums—which come courtesy of Matt Evans—are manipulated to sound like ice cracking. Drones ebb and flow in the same manner as an uneasy current. A deeply unsettling unknown stalks the album’s periphery, but Saxl cloaks it in a palpable sense of awe. There is horror lying in wait on Drifts And Surfaces, but there’s also an abundance of beauty. And if you’ve ever visited Lake Superior during a particularly cool period, the presentational accuracy is as disquieting as those moments can feel.

“If you fall in[to Lake Superior], you risk dying in a matter of minutes. There’s also this sense—once you get outside of the Apostle Islands and you’re in the lake—that you could be swept away into nothingness and nobody would find you,” notes Saxl during a virtual conversation with Tone Madison. Saxl’s upbringing has made her particularly aware of the lake’s lethal duality, which is translated expertly through the bulk of her discography. “Surfaces,” the album’s closing track, is especially emblematic of this awareness. Henry Solomon’s baritone saxophone and Robby Bowen’s glass marimba prod Saxl’s synths, creating a warm and delicate tension. Dread and serenity intertwine across the track, which presents the unmistakable allure inherent to the large bodies of water that help define Wisconsin.

Saxl’s acute articulation of these dynamics, somewhat unsurprisingly, comes from direct experience and a long history with the area. As a child, Saxl says she “grew up mostly in Minneapolis” but would spend summers at her family’s residence on Madeline Island. As an adult, Saxl has been returning to the residence in winter, when the island’s population decreases from its approximate summertime size of 2,500 to just over 200. Through jumping back and forth between New York and Wisconsin, the ambient composer has carved out a genuine appreciation for the state and its odd tics. (During our conversation, Saxl relayed a sincere fondness for Madison’s long-defunct all-ages music and arts venue The Project Lodge, where she used to play shows.) She currently—and accurately—tells people that she’s “splitting time” between the states. Upstate New York is Saxl’s current place of residence.

Enshrining that degree of change as a common exercise seems to have impacted Saxl’s appreciation of the present, which is baked into Drifts And Surfaces‘ proverbial fabric. “Blue Distance was memory. Drifts And Surfaces was present-tense, and trying to really capture what my everyday life was like at that time, which [was when] I was actively living next to Lake Superior,” she says, marking out a critical difference between the two releases. Whether in dealing with hard documentation or abstract expressionism, Saxl’s output has been enormously gripping.

“I’m incredibly influenced by my surroundings. A sense of northern climate is deeply embedded in who I am. I am influenced by what I’m currently around,” says Saxl, ruminating on the profundity of Madeline Island and its surroundings. It’s an influence that manifests on Drifts And Surfaces in arresting fashion. It’s an album that should immediately feel like home to many Wisconsinites, who will undoubtedly find a measure of solace in Saxl’s unlikely tribute to the state’s intimidating—and occasionally overwhelmingly harsh—natural beauty.

Saxl sat down with Tone Madison in early September to discuss how the environment influences her work, the long and winding process of assembling Drifts And Surfaces, embracing a punk ethos, and why she’s not interested in virtuosity.

Tone Madison: Can you tell us about how you’ve been splitting time between New York and Wisconsin?

Elori Saxl: Well, I grew up mostly in Minneapolis. My family has a place on Madeline Island in Wisconsin, so I grew up spending summers there. As a teenager, I would spend whole summers there and work in, like, every job possible there. And then, since I lived in New York, I’ve basically spent every winter on the island. I did that for maybe seven years, and then just fully, coincidentally, right before the pandemic, I moved to the island full-time. And then the pandemic. [I] ended up staying for the next three years straight, and now I’m back to splitting between New York and the island. At some point I just felt that my life [would] be a balance of living between those two places. And sometimes it’s years at a time, you know? So I was like, “I’m just gonna start saying it’s a split,” because it is. But it’s a multi-year split.

Tone Madison: It’s interesting that of all of the times of the year to be in Wisconsin, you’ve been choosing winter.

Elori Saxl: Totally. I mean, I think at first it started somewhat logistically. Because sure, it was a time that no one else in my family wanted to be in the house, and so it was just easy. But then at some point I just fell so deeply in love with winter up there. And, yeah, it’s just a really, really special time. Especially with the lake, it’s just so unique to be up there. And I also love that it’s a [much] smaller community. It’s like a tenth of the size [it is in summer]. And the summer up there is great, but it’s extremely distracting and social, and bugs are [out]. Everything is making noise at that time in the winter. It’s focused and quiet. It’s so beautiful.

Tone Madison: In your work there seems to be a really, really deep-rooted affection for Lake Superior. If you had grown up elsewhere and come to that area without the benefit of those memories, do you think your connection to it would still register as a profound one?

Elori Saxl: Wow. I… hard to know. Yeah, I mean, I think I have a comfort there and a sense of it feeling like home. Every time I think I’m starting a new project with a completely new theme, it keeps coming back to that place. And I think I’ve come to really understand over time that it’s a really deep part of who I am and how I see the rest of the world.

But in terms of a profound or awe-inspiring experience, I do think there’s something that is immediately felt there, regardless of history. Just because of the size and the temperature. Especially when it’s… I mean, yeah, there’s a couple months in the summer that it feels sort of like a vacation land. But the rest of the year, if you fall in, you risk dying in a matter of minutes. There’s also this sense—once you get outside of the Apostle Islands and you’re in the lake—that you could be swept away into nothingness and nobody would find you. So I think there’s a very palpable sense of power and I think you feel small in a way that is somewhat rare these days as a human, to really feel small. So yeah, I do think that awe is somewhat immediately felt.

Tone Madison: It seems like when you’re creating, you’re favoring nature-focused moments. A lot of musicians I’ve talked to haven’t been as conscientious of environment in the composition and creation process, opting to fixate on a more self-contained emotive feeling or response. When you’re composing, do you find yourself differentiating between emotion, environment, and moment, or is that something you approach as a composite whole?

Elori Saxl: I think in general, I’m incredibly influenced by my surroundings. A sense of northern climate is deeply embedded in who I am. I am influenced by what I’m currently around. But I have spent time in places like [Los Angeles], and there’s something that is fighting against my natural sort of resonance.

With the two albums that I’ve put out, it was a little bit different. The way that I was engaging with place was a bit different between the two. With The Blue Of Distance, I was using actual field recordings from places. So in some way, it was more literal. But in the other sense, with that project, I was thinking a lot about memory and the ways that specifics of a place and time start to erode through our memory and also through digital technology. With Drifts And Surfaces, the idea was to really try to capture the present tense as specifically as I could.

Blue Distance was memory. Drifts And Surfaces was present-tense, and trying to really capture what my everyday life was like at that time, which [was when] I was actively living next to Lake Superior. On the other hand, I wasn’t using any field recordings, so it’s all much more just an abstract impression of the place or my interpretation of that place.

Tone Madison: That certainly speaks to the intentionality of Drifts And Surfaces. Were there any unexpected musical byproducts of those attempts to communicate those semi-abstract, overarching ideas? If so, was any of it incorporated into the work?

Elori Saxl: Oh man. Well, I think one thing that has been interesting has been [that] when I wrote those pieces, it was I had thought a lot about what I wanted to try to do ahead of time. But when I actually was writing them, it was [like I was an] improv visitor. I wrote it in, like, one fell swoop.

In the promotion of this record, I went back and was just looking through videos on my phone of like scenes from that time when I was writing it. [Of] videos of ice breaking apart and forming these waves. Or of taking the Windsled—which you take in the shoulder season—to get over to the island, which is like a boat with a big fan on it that glides across the lake. It’s incredibly noisy. In all of these videos, there was just this sense of noise and abrasion.

When I was mixing these pieces, I was thinking a lot about distortion and deterioration, and wanting the pieces to have this sense that they were in the dirt and crumbling and falling apart. It was at that point [that there was a] feeling that I just, like, felt right in my soul. But watching these videos, I [realized] all of this noise was really present during this time. Especially winter life on the island, it’s either natural sounds, like the waves that really just become like noise, or this man-made machinery that’s super noisy. Or plows scraping on ice. Just endless noise.

That was one thing [that] made its way through that I hadn’t been aware of in an analytical way at the time. And I don’t know, I think it’s really easy to get focused on nature in these places in a sort of romantic way. But thinking about this made me realize just how much other stuff is going on. And it’s not pleasant, all this other stuff going on.

Tone Madison: What was the timeline for Drifts And Surfaces, from conception to release?

Elori Saxl: This was like a really long-reaching and meandering project. I began working on [Drifts] in 2018. I was commissioned by this percussion group—Tigue—that’s based in Brooklyn. We worked on it for a year, and that ended in them doing a live performance of it in New York in 2019. And so that was, I guess, technically, the beginning of this whole project. But, yeah, then it basically went from there.

Let’s see: pandemic happened. Then I did this piece for Third Coast Percussion. It was an expansion on those same ideas. Once I had that part, it helped me sort of reframe the first part. I actually ended up fully redoing the entire thing to make the two of those pieces fit together as one bigger piece. Then Surfaces was this commission from the Guggenheim Museum—completely unrelated—for this retrospective on Alex Katz. I made it, like, responding to those paintings. All those pieces, I thought the end result was just the live performances or installations of the music.

I wish I had [been] thinking this through a little bit more in advance, but like a year after I’d finished all of it, I was like, “Oh, I do feel like these all sort of fit together thematically.” Thinking about this idea of capturing the present tense [made me think] I should put it together on an album and put it out. I went through an entire another phase of taking what had been pieces for live performance, which I [have different standards for]. What it needs to accomplish is a bit different than recorded music. There’s just different things I want to make sure are happening if it’s going to be an album. [Something that is] listened to in headphones at home. And so then it was another full year of tweaking things to kind of get the sounds to feel satisfying to me.

Tone Madison: How did you assemble the other musicians who appear on this record? Were they people you had in mind from the jump?

Elori Saxl: So, the two percussion pieces, “Drifts I” and “[Drifts] II.” Those were commissions from people that were asking me to write it, but I ended up actually not using any of the recordings of those people. I just felt that there were things that were happening with an electronic version of those, or sample-based versions, that I was more satisfied with. And then in terms of Surfaces, those were just Henry Solomon, who’s playing baritone saxophone. Robby Bowen is playing glass marimba. [They] are just two good friends and collaborators. And Robby had just purchased that glass marimba, which is a pretty unusual instrument, and he had been posting a bunch of videos on Instagram. And I was like, “Wow, that’s so beautiful.”

This happened to be the same time that I was starting on that commission. I felt like this idea of glass, the Alex Katz paintings deal so much with the reflections on water and surfaces of materials. So glass was an extremely obvious [point]. There’s no depth to that connection. It was just like, “Oh, glass, that’s an interesting material to represent these things.” And the sound is beautiful. So I invited him in. And then Henry is a good friend and frequent collaborator, and I love his playing. I also felt like having a woodwind instrument that has breath involved in it [was important]. Especially how Henry plays. You can really feel the humanness behind his playing. That felt like an interesting way to represent a human throughout the ideas.

Tone Madison: Both “Drifts” and “Surfaces” were commissioned for different purposes. When you are creating for a commission versus when you are creating for essentially public consumption, are there different weights to the pressures that you are feeling?

Elori Saxl: Yes. I find commissions are extremely helpful for me, because mostly, there’s a deadline, and secondly, there are really clear constraints or goals. Skills that the music needs to accomplish. I think when I’m working on work that’s just for myself, I love so many different things that it’s so hard for me to decide where to put my focus. The personal demons’ voice criticisms just get so loud. If there’s no due date, I’ll just sort of let them win. But if there’s a deadline, then it’s like, “Well, I have no choice. I have to turn in something.” And then, [I] pretty much always end up being satisfied with what I made. It’s something that I’m endlessly trying to figure out how to trick myself into feeling. But yeah, there is a different way. I think it’s all mental in the end.

Tone Madison: I’d assumed it may have been slightly different. With something like the Guggenheim Katz commission, you’re effectively tied into being a partial representative or key voice in another artist’s legacy, which seems like it would be an exciting-but-terrifying ordeal. But I do see how pure self-creation’s vast expanse of freedom could be scarier than something with set restraints.

Elori Saxl: I mean, it’s interesting. I think with the Guggenheim thing, the way that it was framed was like, I am responding to this person’s work. So if I was the curator for that job, I think I would be incredibly stressed with representing them properly. But I think with this, if there was a framing of [the music being] me responding to his work, and if I get it wrong, that’s it’s fine, you know? Something that I’ve discovered for myself this past year is that if I’m writing music and it’s just for me, I start thinking that this whole entire endeavor is all about me. I get really uncomfortable and pretty creatively blocked. But if I think, like, “Okay, I’m gonna play this show with my friend who plays cello. Let me write some music that allows him [to shine].” Then I can, bang pieces out endlessly.

With a commission, I love the part of it that’s researching who I’m writing for, figuring out what they’re good at, figuring out what’s interesting to them. And then making a piece that’s specifically built for that person to shine. Even though it’s ultimately my name on it at the end of the day, [a commission is] sort of the exact same thing [as a non-commissioned record], but it mentally frames it in a way that I’m much more comfortable with.

Tone Madison: Is there anything that we haven’t talked about that you would like to touch on, or anything from this conversation you’d like to expand on?

Elori Saxl: Well, just since you’re the Wisconsin representation here… Someone else recently had asked me about the influence of the Island. One thing I was just thinking about is [that] on the Island, it’s inherently isolated, which leads to definitely some bad things. But also a lot of good things, in that people are just really resourceful and good at problem-solving with the things that they have. Because often, to get a piece of lumber or something that you need for a project, it’s multiple days away from happening. So people are really good at both sharing resources and coming up with creative solutions.

There’s this very humble energy that feels very tied to the Midwest. Especially to the Northwoods. You just do stuff, and you don’t make a big deal out of it. And something [about] moving back from Wisconsin to New York [that] has been really challenging for me is [that] there’s a lot of people that are into similar things, like foraging mushrooms. But they’ll make an Instagram account for it or something. Versus on the island, you just do it, and it’s not a big deal. You go home and it can be a private thing. So I have been thinking about how this part of the character of this part of the country [has] really influenced how I like to move through the world and also how I like to make music. I’m never really interested in virtuosity. I’m much more interested in a creative and economical arrangement of pieces based on what I have.

Tone Madison: I have semi-frequent discussions with artists—who tend to lean towards punk—about a dynamic that I’ve chalked up to “feel-based” versus “technique-based.” I’ve always found myself naturally gravitating far more strongly towards the former. And virtuosity is impressive, but it often lacks emotional resonance. Drifts And Surfaces has that resonance, which makes some of what you’re saying here ring especially true.

Elori Saxl: Yeah. And it’s funny, I’ve never been super into punk music, but growing up in the Midwest, I feel like the punk scene is the dominant scene, you know? And it has been really interesting thinking about ways in which that feels like it’s bubbling up through my work. [Especially] in terms of ethos: figure out a way to do whatever you want to do and just do it.

Growing up in high school, everyone around me—and myself—[were] going on DIY tours through the Midwest, and it was no big deal. It’s just what you did. So I think that ethos has always been really important. And lately, some of the sounds are seeping in, but applied to a very different [form]. I’m making music that’s very much not-punk, but I feel like there’s like a distortion and grit that feels like it’s connected.

Tone Madison: There’s connective tissue there, for sure. So, Drifts And Surfaces took about five years to officially come together. Are you giving yourself a break or do you have new work on the horizon?

Elori Saxl: There’s a bunch. This project was, in some ways, unintentionally, the dam that was blocking a lot of stuff. And there’s a bunch of stuff about to come out. I’ve been working on some scores for film and television. Some more collaborative music, instrumental music, and then also some dancier music.

On September 24, I’m announcing a score that I’m releasing as a vinyl record that’s for a PBS TV series about environmental issues in Southern California that will be coming out in mid-November. I’m really excited about the music. And the album artwork is by this guy, Collin Fletcher, who is also someone who I’ve found and really connected with. [Fletcher also comes] from a punk DIY background, and is now [a graphic designer on] records for, like, Charli XCX and Post Malone. We really bonded over this, like, sort of photocopy Xerox aesthetic. So, yeah, really excited about that.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.