The Dane County Jail scrambles to back up its case for eliminating paper mail

County Supervisors are asking some tough questions about a proposed contract with prison-telecoms vendor Smart Communications.

County Supervisors are asking some tough questions about a proposed contract with prison-telecoms vendor Smart Communications.

Dane County Supervisors are now considering a contract that would bring the dehumanizing practice of mail scanning to the Dane County Jail, and put the county in business with a scandal-wracked vendor. Currently, elected officials are weighing the decision without being able to evaluate the Dane County Sheriff’s Office’s (DCSO) claims that the jail needs to eliminate physical mail in order to keep out drugs and other contraband. They are missing some key information: Reliable data on how much contraband enters the jail, how much of it gets in through the mail, and any evidence that mail scanning has reduced harms in other jurisdictions.

Since 2017, prison systems and jails around the country have increasingly deprived incarcerated people of most or all paper mail. This has given for-profit prison telecom vendors yet another opportunity to charge a literally captive population for the ability to communicate with the outside world. Personal mail addressed to a prisoner at a jail or prison that has adopted the practice is digitally scanned. Legal mail and other forms of “privileged mail” enjoy a higher level of Constitutional protection, but can still be inspected and scanned in an inmate’s presence.

Practices vary across vendors and facilities, but prisoners view scanned copies of their mail on tablets or computer kiosks, or receive secondhand paper copies. They never touch the actual envelopes, letters, cards, or photos, which are retained and eventually destroyed. Vendors may also charge prisoners and/or senders for various mail services.

Prisoners’-rights advocates have stressed the emotional and mental-health impact that mail scanning has on incarcerated people. Physical mail helps prisoners maintain a richer sense of connection with family and friends, which in turn helps them lead stabler lives after getting out, which in turn reduces recidivism. Prisoners around the country have frequently complained about getting low-quality or even illegible scans, delayed mail, and the sadness of not being able to physically hold a family photo or a child’s drawing.

Crucially, mail has remained an inexpensive form of communication even as it’s become common practice to charge incarcerated people inflated prices for all sorts of things—commissary items, money transfers, electronic messaging, ebooks, phone calls, and so on. Prisoners don’t have the luxury of shopping for these things on the open market. They have to buy from whichever vendors their facilities contract with.

Evidence suggests that mail scanning has done little to stem the very real problem of overdoses and deaths in prisons, and that prison staff are a much more common conduit for contraband.

Prison officials and vendors invariably say that their main justification for mail scanning is to keep out contraband. That argument has focused particularly on drug-soaked paper. Prisoners’-rights advocates and even a few academic studies acknowledge that prisoners smoke or ingest “drug strips.” But there is scant data on how much of that gets in through mail. Scientific and medical experts also reject the claim—spread through a rash of credulous media reports across the country—that prison staff are falling ill from drug poisoning after merely inspecting mail that allegedly contains drugs.

As Tone Madison first reported in February, DCSO, which operates the jail, has been looking for a vendor that can provide “jail resident communication services,” which would add mail scanning to offerings that currently include phone calls, video calling, and tablets. DCSO’s current contract, with ViaPath, was extended to November 1. The ViaPath contract, approved in April 2020, initially included mail scanning too. ViaPath never got those services up and running for Dane County, and the contract was amended in 2022 to remove provisions dealing with mail scanning.

Dane County’s Public Protection and Judiciary Committee (PPJ), which consists of seven County Supervisors, discussed the mail-scanning proposal during its February 25 meeting while the County was still awaiting bids. After soliciting bids from multiple vendors for a new contract, DCSO decided to go with Smart Communications, based in Florida’s Tampa Bay area. The contract is currently under review and faced some tough questions from PPJ at its June 17 meeting. Several Supervisors spoke with unusual openness about the unsavory reputation of for-profit prison vendors and their reservations about Smart Communications itself. Eight members of the public (including one of the authors of this story, Dan Fitch) registered to speak in opposition to the contract, and nine more registered in opposition without signing up to speak. No one registered in favor.

PPJ voted to postpone any formal action on the contract to its July 22 meeting, but brought it up to discuss on June 30. If PPJ approves it, the contract would go next to the County Board’s Personnel & Finance Committee for review. Then it will require a majority vote of the full County Board for approval. If it passes, the jail would aim to implement mail scanning by January 1, 2026. The contract itself was not made available to committee members or the public until the day before the June 17 meeting.

Supervisors take a skeptical first look

Under this contract, personal mail addressed to Dane County Jail inmates would be sent to Smart Communications’ “digital mail processing center” in Seminole, Florida. The contract calls for Smart to retain original copies for at least 60 days before shredding them. Legal mail would still come directly to the jail, where staff would then open and inspect it in front of the recipient and scan it on a Smart-provided scanner. Inmates would then have access to a digital scan of the legal mail on a tablet, or a paper printout. (This part of the contract doesn’t spell out what would happen to original copies of legal mail after scanning.)

“Stuff having to be sent to Florida is insane,” District 10 Supervisor and PPJ member Keith Furman wrote in an email to Tone Madison ahead of the June 17 meeting. “Residents not being able to get physical items like a photo is insane.”

Other PPJ members are skeptical, but not ready to reject mail scanning if there’s a chance of it preventing harm. District 11 Supervisor and PPJ chair Richelle Andrae summed up that view during the June meeting. “I definitely recognize the rationale for not mail scanning. And I am not willing to take on the risk to say no mail scanning, and then there is an overdose in the jail that could have been prevented. That, that is a hypothetical that I’m very concerned about, when there are real implications. And we have competing evidence on this, from what I gather tonight,” Andrae said. “I just think that we’re in a difficult position on that, and I recognize that there are definitely real concerns that residents and family members had. And am I willing to say for sure [that] I’m willing to make that or recommend that policy choice to the Sheriff’s Office about mail? I’m not comfortable with that.”

District 20 Supervisor Jeff Weigand, the County Board’s resident right-wing gadfly, was the one PPJ member who took a solidly pro-mail-scanning stance. “Is it a relatively small amount of times that we catch something that someone shouldn’t have?” Weigand asked. “Yeah, but it’s also a really, really small percentage of time that someone kills themselves in the jail, and that’s something that we should try to stop.” (Gray responded to Weigand’s comments with a quick aside—”Fine argument for gun control!”—as Andrae briskly kept the conversation moving.)

Supervisors also asked how Smart Communications would handle sensitive user data—likely prompted by concerns about exposing people to ICE or other federal law enforcement ,and exploitative AI practices. Captain Jan Tetzlaff, who worked on crafting the RFP and evaluating proposals for the contract, took the lead on answering the committee’s questions on behalf of DSCO.

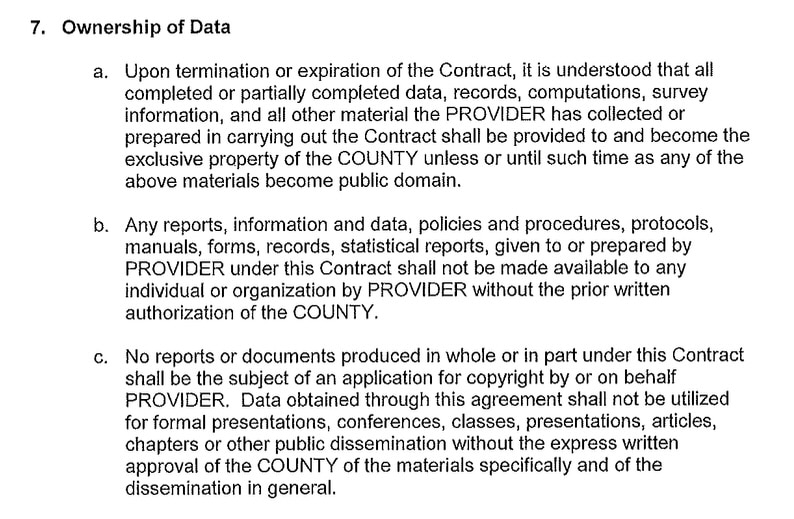

Tetzlaff tried to reassure PPJ that Dane County would own any data the new system generated. In fact, the language of the contract is not that simple. The “Ownership of Data” section of the contract places restrictions on how Smart can use or share certain data—but these terms don’t cover all the different types of data that could be generated, and don’t explicitly forbid Smart using them for whatever else it wants. It states that upon “termination or expiration” of the contract, the data will become the “exclusive property” of the county. What this section never clearly spells out is who would own the data during the contract.

Some language in the contract would, at least on paper, address some of the most common complaints about mail scanning. It requires Smart to “convert mail into high-definition, color, digital files” and to get scans of mail to the jail “the same day it is received at the scanning facility.” The contract does not spell out how DCSO will hold the contractor to these terms, and how responsive jail staff will be to any inmate complaints.

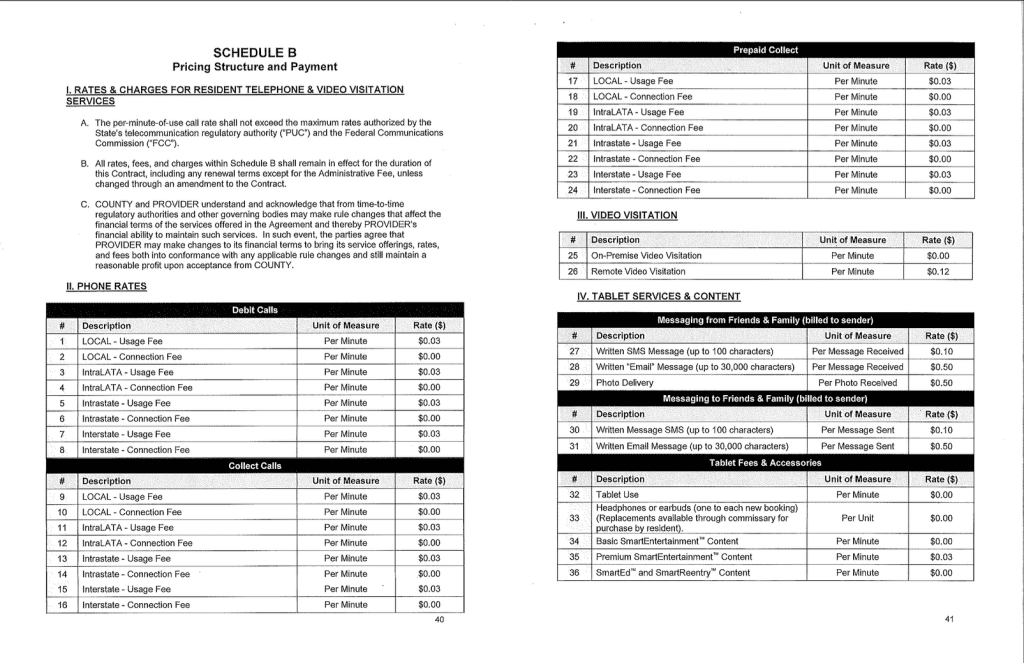

As for what inmates will pay and what they’ll get—well, that’s complicated, thanks to changing regulations and the ever-evolving business models of the prison-telecoms industry.

A “Trojan horse” business model

Nationwide relief for exorbitant inmate phone and video-calling rates was on the way, until it wasn’t. A July 2024 FCC ruling placed new caps on rates for phone and video calling in prisons and jails. For jails in Dane County’s size range (“average daily populations of less than 1,000 incarcerated people”), those took effect on April 1—but for jails with existing telecoms contracts, the FCC built in a grace period that can extend as far as January 1, 2026. As a result, the rate caps haven’t taken effect yet, in Dane County or a lot of other jurisdictions. And on June 30, the FCC reversed course, announcing that it would push back compliance deadlines until April 1, 2027.

The FCC’s 2024 ruling dealt only with phone and video calling—not with rates for the other things Smart and its competitors offer, like paid messages, photos, or the various media purchases and subscriptions available on tablets. That’s important, because the less these companies make from calls, the more their bottom lines will depend on other offerings. Even in Minnesota, which made phone calls free for inmates in state prisons starting in 2023, there’s money to be made. The Lever estimated that, “an ever-increasing array of non-phone prison services” still generated almost $3 million in revenue for private contractors and hundreds of thousands of dollars in kickbacks for the Minnesota Department of Corrections in 2023.

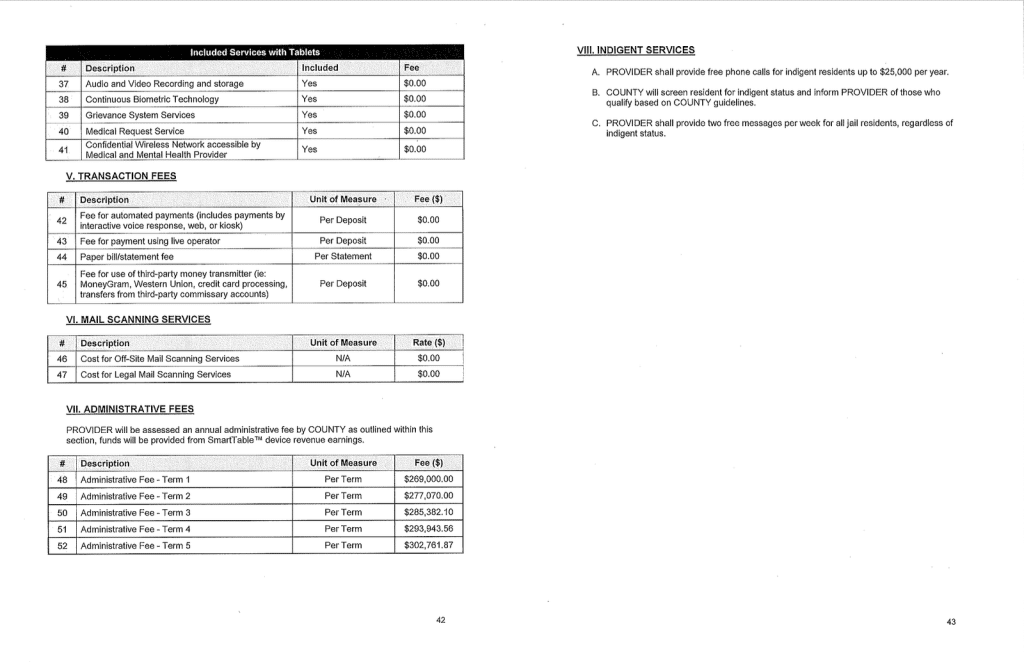

The pricing tables in Smart’s proposal comply with the now-imperiled rate caps, sometimes even dipping lower. Smart plans to charge $0.12 per minute for video calls, in comparison to ViaPath’s current $0.25 per minute video charge. In addition, the contract would require Smart to provide up to $25,000 worth of free phone calls for indigent inmates per year. It also requires Smart to give all inmates two free messages per week.

Providers generally call cheaper, shorter messages “texts” or “SMS” because that’s how the public thinks of them; however, both kinds of messages go through the provider’s systems and appear on a tablet as plain text, usually stripped of emoji and formatting. (Can’t have anyone expressing themselves too much.) Smart plans to charge $0.10 per message of 1000 characters or less (“SMS”) and $0.50 per message of 1,000 to 30,000 characters (“email”). For comparison, ViaPath currently charges $0.15 for messages with 2,000 characters or less in Wisconsin’s state prisons.

In its pricing tables for Dane County, Smart Communications proposes to provide the mail scanning itself for free. That’s because Smart and its competitors build their business model around selling inmates on a whole suite of paid services, and ideally selling clients on an array of accompanying software tools. Commonly, these vendors provide tablets for free as well. In a deal like this, Smart wouldn’t get most of its money directly through Dane County’s coffers. In fact, Smart would pay the county an annual fee, ostensibly making up for the staffing and IT costs the county incurs while implementing these services. For companies like Smart, the real value is securing exclusive access to a captive market.

The proposed contract includes educational content pricing, but it’s unclear what these “Basic SmartEntertainment™” and “Premium SmartEntertainment™” packages include. Those terms don’t appear on Smart’s page about its tablets. No prices are locked in for music, books, movies, or any of the other “rented” content people can access via their tablet. This may allow Smart to jack up prices at will, and leaves the county with no control over how much our yet-to-be-adjudicated poor folks in jail will get bilked.

And Smart Communications would have a chance to raise phone and video calling rates—though it would need the county’s approval—if the FCC or a court threw out the 2024 rate caps entirely. This is a real possibility, given all that the Trump Administration has done to weaponize the FCC and erode its independence. A clause in the contract’s pricing section states:

COUNTY and PROVIDER understand and acknowledge that from time-to-time regulatory authorities and other governing bodies may make rule changes that affect the financial terms of the services offered in the Agreement and thereby PROVIDER’s financial ability to maintain such services. In such event, the parties agree that PROVIDER may make changes to its financial terms to bring its service offerings, rates, and fees both into conformance with any applicable rule changes and still maintain a reasonable profit upon acceptance from COUNTY.

In court testimony quoted in a March 2025 story from The Lever, Smart Communications CEO Jonathan Logan called his company’s MailGuard product a “Trojan horse,” and explained the business logic of not charging directly for mail scanning: “We actually… make more money by giving [MailGuard] away for free and getting all the revenue-generating services.” Left unsaid is that the inconvenience of mail scanning might also prompt more inmates and their outside correspondents to just cave and use more paid electronic messaging. Indeed, Smart’s proposed contract with DCSO mentions that Dane County can later opt into the new smartwatch product Smart is pitching for inmates—which serves as both a messaging device and a surveillance device. Logan has touted it as “the most advanced technology ever created for the corrections industry.”

Where’s the data?

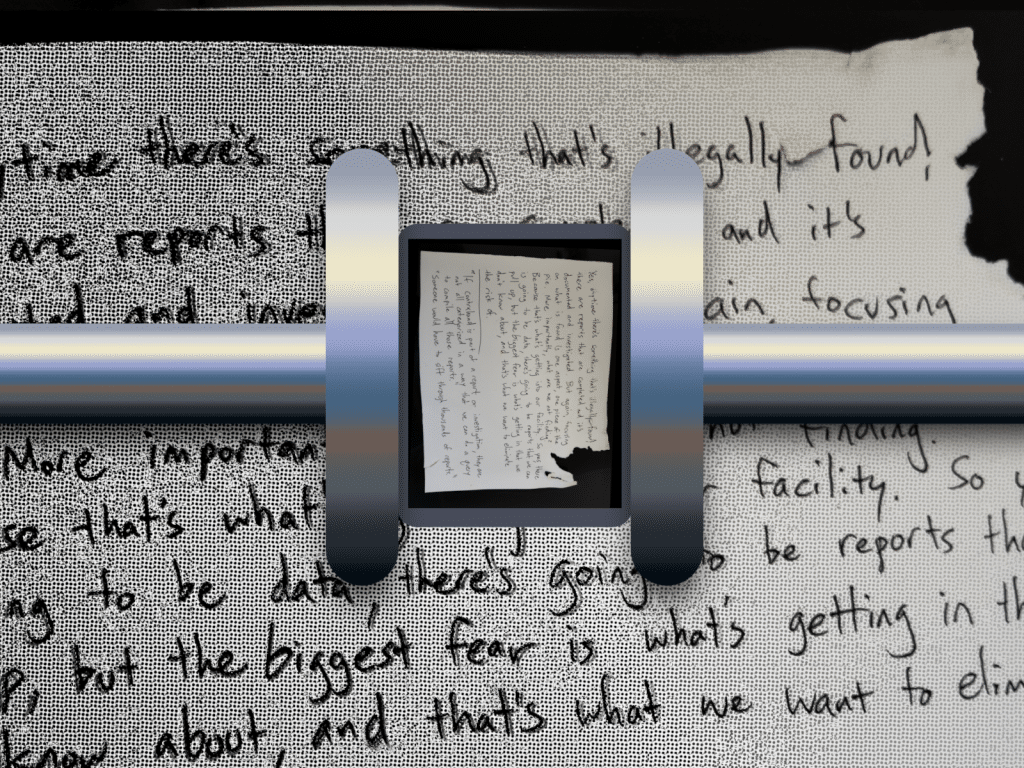

PPJ members still don’t have answers to questions they asked DCSO at February’s meeting. During the February meeting, two committee members—Andrae and District 36 Supervisor David Peterson—specifically asked Sheriff Kalvin Barrett for data on contraband entering the jail and more information on drug-tainted paper. Barrett’s replies indicated that DCSO could and would provide that data:

Richelle Andrae: Thank you, Sheriff. I think something that would help me wrap my mind around this particular component would be a little bit more data. You mentioned some specific cases where there was some drug [or] dangerous substance coming in through the mail. Would that be any type of data your office has collected in the past—like we know that this many pieces of mail actually did have a substance use issue that we found in the last year—something like that, to help me understand the scope of that concern?

Kalvin Barrett: Yes, anytime there’s something that’s illegally found, there are reports that are completed and it’s documented and investigated. But again, focusing on what is found is one aspect, one piece of the pie. More importantly, what are we not finding? Because that’s what’s getting into our facility. So yes, there is going to be data, there’s going to be reports that we can pull up, but the biggest fear is what’s getting in that we don’t know about, and that’s what we want to eliminate the risk of.

Nearly five months later, DCSO has provided the committee with only partial and verbal answers about contraband data—and is claiming that a more comprehensive data set either doesn’t exist or would be too laborious to dig up. At the same time, DCSO officials are referring to vague or generalized figures in an effort to bolster their case. Elected officials are sizing up the proposal without even a reliable estimate of how much contraband deputies find at the jail, how much of it consists of dangerous drugs, how much comes in through mail as compared to other channels, or what DCSO has determined from follow-up investigations about these incidents.

Tone Madison also asked DCSO spokesperson Elise Schaffer for contraband statistics in a February 18 email, and received no response to that question. After some follow-up in June, Schaffer wrote back: “We do not keep a record specific to contraband in the jail.”

Asked for clarification, Schaffer wrote that DCSO doesn’t keep aggregate data of jail contraband incidents or categorize reports in a way that would allow it to filter out those incidents specifically. “If contraband is part of a report or investigation, they are not all categorized in a way that we can do a query to compile all of those reports,” Schaffer says. To get that data, Schaffer explains, “someone would have to sift through thousands of reports.”

Provided with the above transcript excerpt of an exchange between Andrae and Barrett, Schaffer replied: “I don’t know what the Sheriff is planning to present at a future PPJ meeting. My guess is he will have examples to provide, but it won’t be hard statistics/data.”

Tone Madison filed an open records request with DCSO in February seeking data on reported contraband incidents at the jail since 2015, and internal policies/guidelines dealing with contraband. DCSO has provided a couple of policy documents, but records staff says it’s still working on the main part of the request.

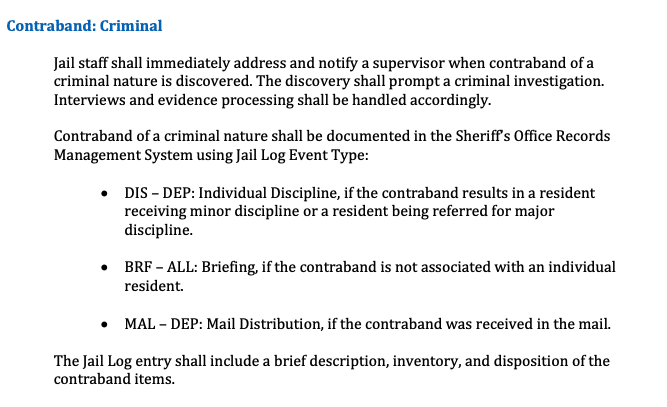

But DCSO’s own policies require staff to keep records of contraband they find, whether it’s “criminal” contraband like drugs, or contraband that is legal but not allowed in the jail. DCSO’s Security Services Manual includes specific procedures for handling contraband and processing inmate mail. (DCSO provided copies of these chapters in response to our open records request.) The manual’s contraband policy clearly instructs jail staff to log and categorize these incidents in a specific way:

Contraband of a criminal nature shall be documented in the Sheriff’s Office Records Management System using Jail Log Event Type:

- DIS – DEP: Individual Discipline, if the contraband results in a resident receiving minor discipline or a resident being referred for major discipline.

- BRF – ALL: Briefing, if the contraband is not associated with an individual resident.

- MAL – DEP: Mail Distribution, if the contraband was received in the mail.

The Jail Log entry shall include a brief description, inventory, and disposition of the contraband items.

Contraband of a criminal nature shall be documented in the Jail Log as described above and with an incident report in accordance with Sheriff’s Office Policy & Procedure 600.06 – Incident Documentation. The incident report shall include a description, inventory, and disposition of the contraband.

If jail staff are following this policy, then—at least in theory—DCSO must have some way to pull up incidents involving mail and incidents that resulted in discipline or criminal charges. Asked about this, Schaffer counters that the tagging system described above still doesn’t enable a comprehensive way to pull up contraband incidents. “The searches for data are only as good as the information recorded…there could be something discovered, but if the deputy doesn’t use the word contraband to describe it, it won’t show up in a search,” Schaffer says.

Asked point-blank whether this is an acknowledgement that DCSO’s records are incomplete or unreliable, Schaffer responds: “I wouldn’t put it that way. We’ve been clear that we have not historically tracked the specific data you are requesting (incidents of drugs entering the jail through the mail).”

The Security Services Manual also states that the discovery of criminal contraband “shall prompt a criminal investigation.” Elsewhere, the Mail policy section of the manual states that “The Mail Clerk shall notify a supervisor anytime criminal contraband is received in the mail.”

During February’s meeting, Barrett told PPJ members about “a situation where K3, which is a synthetic drug, was found on a letter that was trying to come into our jail. But the great work of our deputies was able to scan that, identify it, test it, and confirm that it was an illegal substance trying to come into our jail.” Barrett didn’t provide any other details about this anecdote at the time. Schaffer says Barrett was referring to an October 12, 2024 incident in which deputies, acting on a tip, conducted a search and found legal papers in one inmate’s cell that “tested positive for K3,” and that some of the papers “had corners torn off.” But Barrett’s description—”trying to come into our jail”—implies that deputies intercepted the letter before it reached its intended recipient. Schaffer describes deputies finding these papers after the inmate had received them and torn off pieces.

“It does not appear that charges were filed,” Schaffer adds about this incident. Asked for additional details on this incident, Schaffer provided a case number and suggested filing a records request for the reports. Tone Madison has filed that request and is still awaiting a response.

Numbers are key for evaluating DCSO’s pitch for mail scanning, particularly given a few other statements Barrett made at the February PPJ meeting. At one point, he said: “They’re finding new ways to get things into our facility, and so by going from screening to scanning, it completely eliminates any possibility of anything illegal coming into our jail system from the outside.” This is a head-scratcher: If the first part of that statement is true (and it is, because people who smuggle things are indeed always trying to get past evolving security measures), then the second part could not possibly be true. Barrett later told PPJ members that “The number-one way that illegal drugs get into facilities across the country is, if not through the individual, it’s through the mail.” Tone Madison asked Barrett, in a February 28 email, if he could share any data he relied on in making this statement. Barrett has never responded.

Data on contraband, overdoses, Narcan use, and criminal referrals would also shed light on the effectiveness of measures DCSO is already taking.

At least some of the sifting Schaffer mentions has taken place. When Furman, during the June meeting, pressed Tetzlaff on the committee’s earlier requests for data, she replied: “[We] haven’t specifically been tracking it, as far as the drugs coming in, but I did have a staff member review the reports that we have on file for a variety of different incidents. And […] since 2021, I have 10 cases where we have definitively identified drugs in the jail that appear to have come from a mail source.” Tetzlaff went on to note that “in 2024, we had 40 incidents that were tagged as drug-related in the jail.” Tone Madison asked Schaffer to comment on or confirm the numbers Tetzlaff shared; as of our deadline Schaffer has not addressed those questions directly.

This Schrödinger’s-data situation has also begun to haunt other local media coverage of the mail-scanning proposal. Barrett told Channel 3000 in a June 30 report: “While the numbers may not show a significant amount of illegal controlled substances coming in, that’s because there’s a high likelihood that we’re missing them, and that’s what’s even scarier.” The story never specifies what “the numbers” are or how Barrett obtained them. Barrett has a fair point when he notes that DCSO is likely missing some contraband that comes in. Any data set dealing with criminal activity is inherently incomplete, because the authorities never find out about an unknown (but significant) number of crimes. This fact has never stopped police from using what data they do (or don’t?) have to argue for preferred policy outcomes—as Barrett has just demonstrated.

Tetzlaff’s numbers do not convince former District 33 Supervisor Dana Pellebon that mail scanning is necessary. While serving on the County Board from 2022 to 2024, Pellebon worked to broker compromise on the prolonged effort to build a new Dane County Jail, advocating for a smaller facility overall and pushing DCSO to adopt more humanitarian reforms.

“We shouldn’t change an entire mail system that is a meaningful personal connection to family for the two pieces of mail a year, out of thousands, that may have contraband,” Pellebon says. “The low numbers show that the system in place is working and that the Sheriff’s Office is handling this with care and precision.”

When PPJ met again on June 30, Tetzlaff elaborated on these numbers—though not by much, and it’s still not clear how they were derived or how they square with Schaffer’s explanation that data is hard to extract from jail logs. Tetzlaff told the committee that the jail handles about 16,900 pieces of mail per year. From year to year, she offered the following numbers about drug investigations:

2022: 36 drug investigations. 2 tied to mail. 2 from unknown sources. Used Narcan 13 times

2023: 46 drug investigations. 3 tied to mail. 6 were unknown sources. Used Narcan 16 times.

2024: 41 drug investigations. 4 tied to mail. 7 from unknown sources. Used Narcan 27 times.

2025: 11 drug investigations. 1 tied to mail. 2 from unknown sources. Used Narcan 6 times.

This suggests that jail staff have allegedly found drugs in less than one percent of the mail items they’ve inspected in the past three and a half years. DCSO still has not claimed, even anecdotally, that drugs coming in through the mail have been responsible for any overdoses or deaths.

During the June 30 meeting, supervisors pushed for more information on how contraband enters the jail. Barrett replied: “I would suggest that if we’re going to have a specific conversation in regards to how people are smuggling drugs into our jail facility, I’d prefer to do that in a closed session, just for safety purposes moving forward.” This didn’t happen, because the meeting agenda didn’t include notice of a closed session and the committee would first need to figure out a legal justification for a closed session.

Wisconsin’s open meetings law allows for government bodies to meet in closed sessions only under certain circumstances. Vague claims of “safety purposes” do not suffice. One provision in the law allows closed sessions when “considering strategy for crime detection or prevention,” but at this point the committee was already having an open discussion about preventing drug smuggling in the jail, and the prevention strategy in question is clearly spelled out in the contract. A broader discussion of jail staff bringing in drugs would not necessarily cut it, unless it dealt with specific investigations or disciplinary proceedings. Finally, the Wisconsin Department of Justice’s Open Meetings Law Compliance Guide notes that “mere inconvenience, delay, embarrassment, frustration, or even speculation as to the probability of success would be an insufficient basis to close a meeting.”

Additionally, DCSO has publicly disclosed at least some information about drug smuggling in the jail before: In 2022, DCSO accused a woman of trying to use a contact lens case to smuggle drugs into the jail. When the jail acquired two full-body scanners in 2018, coverage in local media outlets quoted several different DCSO officials who discussed various smuggling methods, like swallowing balloons or, as Channel 3000 put it when paraphrasing a comment from Schaffer, hiding things in “private areas.” A broader discussion of how contraband gets into the jail would not require DCSO to discuss any sort of dangerous or new information that would outweigh the public interest of transparency..

Dr. Elizabeth Salisbury-Afshar, an addiction medicine doctor at UW Health and a professor who teaches in the UW-Madison Addiction Medicine Fellowship Program, says she is not familiar with any publicly available data on how contraband is brought into carceral facilities. When asked about evidence for scanned mail reducing overdoses, Salisbury-Afshar says, “I think it’s hard to measure impact here. I think this is hard to study, and I’m not familiar with any group that has studied this in a scientifically rigorous way.” On the topic of what makes our community safer, Salisbury-Afshar stresses the need for a holistic approach. “We know that ensuring people have access to naloxone, and ensuring that people with a diagnosis of opioid use disorder have access to medications are both very effective interventions to reduce risk of overdose death at the time of release,” she tells Tone Madison. “Linkage to ongoing care in the community is crucial, and to do that people need insurance […] Beyond that, we know there are many things people need to be successful in recovery: housing, steady income, strong social networks, and supports.”

In all fairness, Barrett and his predecessor Dave Mahoney have supported harm-reduction and medication-assisted treatment approaches to the opioid epidemic—which do have a lot of data on their side—not just restrictive contraband measures. Mahoney was advocating for a Narcan program at DCSO as early as 2014, and oversaw a 2016 pilot program that administered Vivitrol to 20 inmates. Barrett has expanded on efforts to offer medication-assisted treatment and voiced his support for Public Health Madison and Dane County’s rollout of harm reduction vending machines. Still, treatment and diversion programs aren’t available to everyone Dane County locks up or prosecutes. More restrictive measures impact the jail’s entire population.

Andrae asked Barrett, during PPJ’s February discussion of mail scanning, to address the human impact of the practice. “Is there any concern that with scanning of mail, that residents in the jail would not be able to engage with their family members?” she said. “You know, you’re receiving a card, it feels different than if you’re just getting something on your iPad, perhaps, and maybe there’s a good efficiency argument to say, ‘We actually get this to you faster if a machine is doing it.’ And there’s a timely component to that. But is that a concern that weighs into this tradeoff consideration at all or no?”

Barrett answered: “There’s not a concern from the Dane County Sheriff’s Office.” After some back-and-forth, Barrett elaborated, arguing that the goal of preventing overdoses outweighs the drawbacks: “While I do understand and respect that there is a component to physically touching something, our ultimate goal is to make sure that that individual is alive to read whatever is coming through.”

The point isn’t lost on PPJ members, but they still have only a vague measure of the problem. Tetzlaff’s numbers suggest that 10 out of 134 drug investigations in the jail since 2022 were tied to mail. That leaves the public and elected officials in the dark about what happened in the other 124 cases.

A touch of panic

Much of the argument for mail scanning (and for other restrictions on inmates’ access to books, packages, and in-person visits) centers around claims that drug-soaked paper endangers corrections staff who inspect or handle inmate mail.

Scientific and medical experts have repeatedly debunked claims that people can overdose on opioids by accidentally touching or simply being near them. They keep having to debunk these claims, because cops, politicians, and media outlets keep spreading stories about first responders overdosing, falling ill, needing Narcan, and/or being hospitalized after accidental exposures. Toxicologists have surmised that people in these situations are suffering not from drug poisoning but from panic attacks. That’s because it’s close to impossible for powder or liquid fentanyl to permeate skin and enter the bloodstream in significant amounts, unless it’s in a patch specially formulated for transdermal delivery. One toxicologist in 2022 went so far as to experiment on himself to make this point, after accidentally spilling an IV bag of liquid fentanyl solution on his hand.

An entire subgenre of this panic focuses on prison guards getting sick after handling paper allegedly tainted with opioids, synthetic cannabinoids, MDMA, or amphetamines. Again, doctors and toxicologists say not so fast.

“There’s simply no danger of somebody getting sick from incidental exposure to cannabinoids, including synthetic cannabinoids, like your K2 and your spice, or amphetamines, methamphetamine, and also MDMA, which we also call molly or ecstasy, in that category,” says Andrew Stolbach, an emergency room doctor and professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “There’s no danger of people getting unintentionally or accidentally exposed.”

DCSO hasn’t made any anecdotal claims (at least that Tone Madison could find) about any such incidents happening to staff at the Dane County Jail. Tetzlaff claimed during the June 30 PPJ meeting that mail scanning “reduces the danger for our staff in searching the mail,” but didn’t specify why she thinks it’s dangerous now. Jail policy requires staff to wear protective gloves while searching inmate mail, and requires that the mail clerk provide naloxone and additional protective equipment.

It’s key for media outlets to follow through, because there are still no scientifically proven incidents of the kinds of exposures these stories describe. As Stolbach and his co-authors put it in a 2020 journal article examining media reports about opioid exposures among first responders, “Seemingly, the only ‘proof’ of exposure was that the victims thought they were exposed.” That’s because they weren’t exposed, because that just isn’t how these drugs work.

“These materials [synthetic cannabinoids, amphetamines, and MDMA], just like opioids, are not absorbed well through skin at all—only in trivial, clinically insignificant amounts,” Stolbach tells Tone Madison.

Stolbach often confronts an understandable question: Even if you can’t get exposed to dangerous quantities of drugs this way, what’s so wrong with erring on the side of caution? For one thing, unfounded fears could make people go beyond scientifically justified precautions, which means they might hesitate to intervene in life-or-death situations.

“If somebody [is having an] opioid overdose and they’re not breathing, every second counts. Every second they’re not breathing, they’re dying,” Stolbach says. “And we worry that people are going to get the message that incidental exposure to drugs is gonna make you sick, just being around drugs is going to make you sick, people are gonna be afraid to help people by treating them with Narcan, aka Naloxone, and get them breathing again, by putting them in a position where they can breathe better.”

From Stolbach’s perspective, the accidental-exposure myth also does a disservice to prison and jail staff. This is a bit ironic, because prison-guard unions are among the leading voices spreading fears about these exposures and pushing for the broader adoption of mail scanning. But Stolbach wants to reassure guards that they can handle inmate mail without overdosing on drugs.

“If I was somebody working in a prison, if I was somebody working in a jail, somebody that had to handle inmate mail, I would have no concern about getting sick or absorbing any of [these drugs] unintentionally,” Stolbach says. “It’s better for them if they can do their jobs without worrying about things they don’t need to worry about.”

Scientific and medical researchers have published a few studies focusing specifically on drug-soaked paper in jails and prisons—and they do consider it a growing public-health threat. These don’t address claims about accidental exposure. Instead they’ve focused on the “severe health outcomes” drug strips can cause for inmates who smoke or ingest them and improved testing for synthetic cannabinoids. A 2019 study from the Allegheny County, Pennsylvania Medical Examiner’s office does note an incident in which local jail staffers fell ill after a “possible exposure to synthetic cannabinoids,” but doesn’t focus on the question of whether or not those drugs actually made them ill.

Profit, surveillance, and scandal

As journalist Nitish Pahwa detailed in a 2023 piece for Slate, the modern prison-telecoms industry began to take shape after the breakup of the Bell System’s telephone monopoly in the 1980s. At the same time, the modern war on drugs and wave after wave of “tough on crime” policies pushed the United States’ prison population into a decades-long surge. This created a business opportunity for other private players to provide telecoms services for incarcerated people, create new surveillance tools, and sweeten the deal with kickbacks to government clients. It grew into a multi-billion-dollar sector, with publicly traded giants ViaPath and Securus on top.

A privately held challenger to ViaPath and Securus, Smart Communications has been especially ambitious about promoting mail scanning, and has even patented a system for it. The company estimated that it earned about $70 million in revenue in 2024, the Tampa Bay Business Journal reported in February.

Smart Communications has also punched above its weight when it comes to demonstrating three main reasons that for-profit prison vendors warrant more scrutiny from elected officials, regulators, and the broader public:

–One, the ethical implications of profiting from inmates and their families: A March 2025 story from The Lever details a bruising family feud behind the company, noting along the way that Logan owns a $10 million yacht named Convict and several luxury cars. (Logan is quoted in the story noting that his Rolls-Royce is 10 years old, in an apparent attempt to upend reporter Katya Schwenk’s preconceptions about rich people. Seriously. Read the whole piece, it’s breathtaking.)

–Two, the cozy, conflict-of-interest-prone relationships these companies cultivate with law enforcement: The Appeal reported in 2022 that Smart had courted five different sheriff’s offices around the country with offers of Caribbean cruises and other travel expenses. The Lever‘s story also touches on this, and links to a federal court filing that describes a sheriff’s captain in Arkansas rebuffing a similar proposal from Smart, stating that it “was borderline criminal and definitely was unethical.” We could not find the word “cruise” in Smart’s proposed contract with Dane County, so that’s one good sign. But it does offer to give up to four Dane County staff members free registration for Smart Communications’ “Annual User Conference.”

–Three, the tendency of their technologies to expand the surveillance of an already heavily surveilled population: In 2021, Motherboard obtained an unsuccessful proposal for the Virginia Department of Corrections in which Smart offered to maintain a searchable database of information on both prisoners and their outside correspondents.

Like just about every company in this space, Smart presents its work as a humanitarian effort to help inmates connect with their families and friends, instead of an expansion of our technofeudalist panopticon. The Lever also notes that Logan served jail time after pleading guilty in 2008 to a felony charge of aggravated stalking. In the story, Logan points to this as the inspiration for Smart Communications and says, “I know the pain that [incarceration] causes.” Still, it wasn’t a crime of poverty that landed Logan in jail. The story details a wealthy upbringing. The criminal charges stemmed from a dispute in which Logan was accused of impersonating a business associate in a series of “erotic services” postings on Craigslist.

The most unusual feature of the June 17 PPJ meeting—aside from elected officials in Dane County actually trying to exercise some oversight of law enforcement—was the sheer dismay that Supervisors openly expressed about the reputation of a potential County contractor and about the prison-telecoms industry as a whole. Several committee members had clearly seen at least some of the reports linked above.

“I recognize that many of the companies in this space are as shady as the one that we’re currently under consideration,” District 14 Supervisor and PPJ member Anthony Gray said at the meeting. “But for me, this isn’t a financial question. It’s really a question of Dane County values. Do we want to be in a position where we’re allowing a private-sector company to milk the residents that are under our care as a mechanism for them to reach out to the community and their own families? I don’t think so.”

Gray went on to reflect on his own experiences as an attorney practicing criminal and business law. “One of the things I see in my day job is what happens when inmates and residents are not able to connect with whomever they love outside of the judicial system, it has a deleterious impact on their behavior,” Gray said. “If I were a Sheriff, I would much rather be around someone who’s in regular communication with their mother, father, sister, brother, pastor, whoever it is that they use to decompress, than someone who is isolated, alone, and growing increasingly frustrated.”

In response, Tetzlaff emphasized the nuts-and-bolts rationale for selecting one vendor over others, saying that DCSO found Smart’s offerings best suited to the jail’s needs. “I’m not familiar with their reputation, except for what I’m hearing here,” she said.

As the discussion went on, Peterson said: “What little research I did, it was very disheartening to see how some of the leadership in both of these companies [ViaPath and Smart Communications] operates…it leaves a pit in my stomach.”

If, as a county, we really care about the end goal of reducing harm, we should look at other places where mail scanning is not the panacea its boosters claim. In Wisconsin prisons, mail scanning did not stop a series of deaths that got a warden and other workers arrested. In Pennsylvania, mail scanning led to pleased officials, but poor quality photos that disconnected incarcerated people from their lifelines. And in fact, overdoses did not decrease.

In the end, it always comes back to the money. The sheriff claims mail scanning is about harm reduction, but true harm reduction would involve figuring out how to keep poor people connected to their community, with less folks in cages: getting people real, uncoercive addiction help, and the support they need to flourish. Mail scanning gets the sheriff easier surveillance, and it gets a shady corporation a foot in the door to squeeze money out of an unfortunate, largely helpless population, many of whom are theoretically still innocent until proven guilty.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.