Crises of faith and fortune in “The Phoenician Scheme”

David Boffa and Sara Batkie contemplate the spiritual and reflexive dimensions of Wes Anderson’s latest deadpan adventure.

David Boffa and Sara Batkie contemplate the spiritual and reflexive dimensions of Wes Anderson’s latest deadpan adventure.

In our “Cinemails” column, two writers exchange viewing notes on a recent theatrical or streaming experience and/or dig into something more broadly philosophical about the movies.

Nearly 30 years after his heist comedy debut feature Bottle Rocket (1996), writer-director-producer Wes Anderson is still dedicated to the particulars of his increasingly production design-focused craft. Audiences instantly recognize his aesthetic: symmetrical diorama-like set decoration, generously quarrelsome ensembles, and adventurous antics delivered with a whip-smart deadpan tone. Anderson has managed to churn out a new project every two to four years, like clockwork.

Those intervals have only seemed to tighten this decade, in arguably Anderson’s most prolific period yet. The 2020s have seen Anderson release three features plus four individually released shorts that make up the Roald Dahl-inspired anthology, The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar And Three More (2024).

The Phoenician Scheme (2025)—currently showing locally at Flix Brewhouse, AMC Fitchburg 18, and Marcus Point Cinema—premiered at Cannes in mid-May, and quickly got a wide U.S. rollout less than two weeks later. And nearly one month after that, it has stuck around in Madison area theaters. Besides the name recognition, perhaps there’s a reason: the film is the most narratively straightforward and consistently rollicking in his filmography in quite some time. And maybe its darting, whimsical charms are a temporary remedy for the brazenly corrupt ills exuding from the daily news cycle.

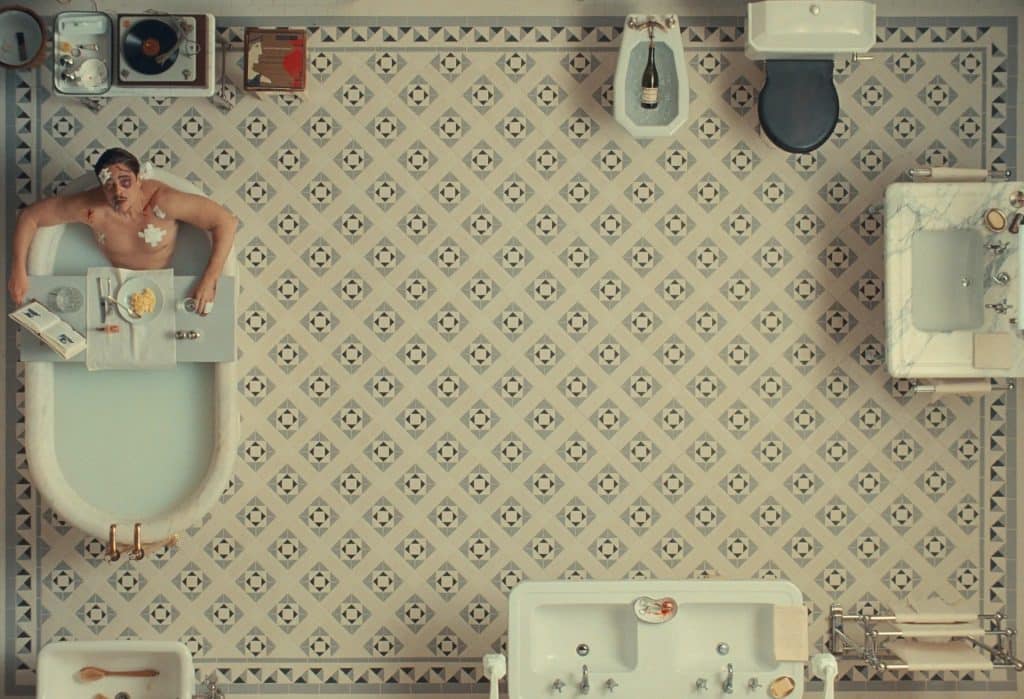

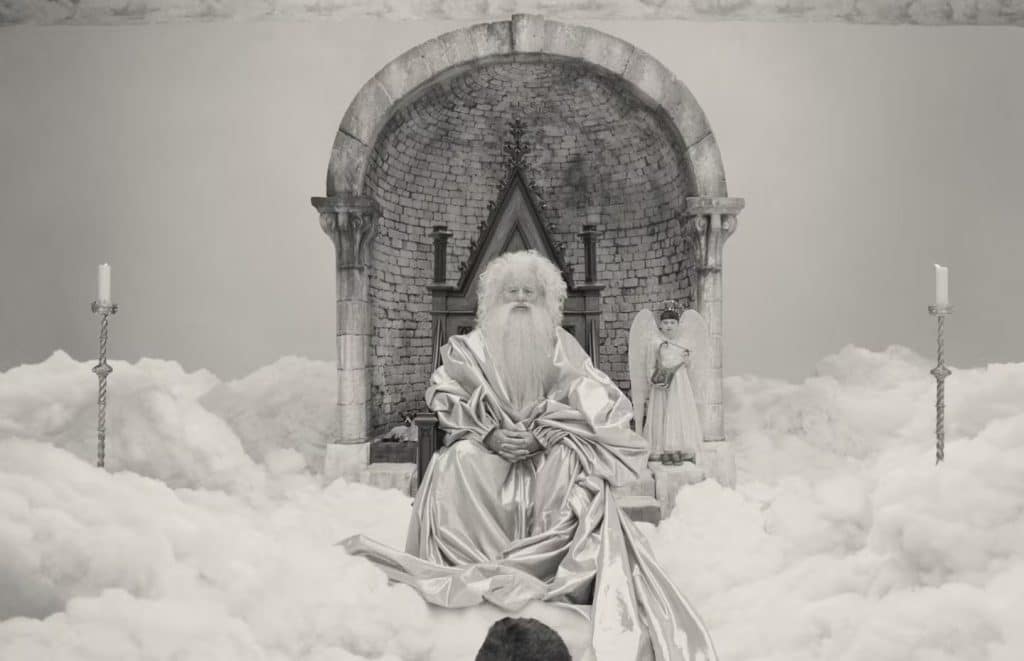

The film’s structure and presentation will be familiar to Anderson faithful, as a fantastical, subversive geopolitical caper that also functions as a precious period piece and an irony-laced family drama. High above the Balkan Flatlands in 1950, aging industrialist, smuggler, and schemer “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio del Toro) is nearly assassinated aboard his private plane. Upon miraculously surviving, he has a come-to-God moment (literally, in a black-and-white-rendered hallucination before the Heavenly gates and court). Knowing he may soon meet his maker at the hands of assassins, Zsa-Zsa decides to recruit an heir to his “business operations.” Bypassing his nine sons, he summons his estranged daughter and novitiate Liesl (Mia Threapleton, the breakout deadpan show-stealer) to his luxurious abode to go over the paper details nestled in a series of shoeboxes. At least, that’s the initial gist of it.

Within that framework and the duo’s inevitable embarking on tangible quests and wild goose chases alike, Anderson explores redemptive themes of the father figure. Of course Anderson been known to indulge in that fruitful tradition, dating back to The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), but he takes some virtuously intriguing and reinvigorating stylistic detours to explore the two principal characters’ faith—in God and each other.

Regular Tone Madison contributors David Boffa and Sara Batkie felt inspired to share their evolving reactions to the film in our first “Cinemail” in over six months and of the 2025 year. In their dialogue, Boffa and Batkie hone in specifically on the film’s lyrical turns, but also delve into the greater meaning and evolution of “style” in Anderson’s dense filmography and, amongst other things, how film as a medium conveys a complicated collective nostalgia for a bygone era. —Grant Phipps, Film Editor

Editor’s note: The following conversation contains spoilers.

David Boffa to Sara Batkie

subject: “The Phoenician Scheme” and the (stylistic) gap

My first thought after seeing The Phoenician Scheme was that this is Wes Anderson’s best film since 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, or at least my favorite since then. This film didn’t pack the same emotional punch of the earlier one, but I think the striking stylistic evolution has origins first seen in Asteroid City (2023), a film with segments whose visuals and editing style feel distinct from everything prior. It is also damn funny—I’m not sure I’ve ever actually laughed out loud this much in a Wes Anderson film—and is the most overtly political and religious in Anderson’s filmography (admittedly not a very high bar, but it’s still significant for his oeuvre).

I can’t help but start by talking about the film’s formal elements. These are easily the most salient and discussed aspects of Wes Anderson—though I also think the most misunderstood as well (and clearly the most parodied). A brilliant and adorable recent Instagram reel made by the amazing people who run the Milwaukee Public Library’s socials foregrounds some of the qualities popularly associated with the Wes Anderson aesthetic: symmetrical compositions, overhead shots of objects, snappy or deadpan dialogue delivery, very particular typography and color choices.

The immediately recognizable formal qualities of Anderson’s films are also polarizing. There are viewers for whom everything after a certain high watermark (e.g., 1998’s Rushmore, 2001’s The Royal Tenenbaums, and 2012’s Moonrise Kingdom) was a step in the wrong direction. Nestled in these criticisms are arguments that his films are increasingly just examples of Wes Anderson doing Wes Anderson—i.e., at some point he just devolved into unironic self-parody of his own signature style. Like, the style was no longer in service to the story but rather the other way around (a point I disagree with but that seems to be the claim—to see Wes Anderson actually parody himself, consider the delightful Mont Blanc commercial he recently did).

To be fair, I think Wes Anderson’s early films are brilliant. I can understand why a certain viewer might have preferred them had Anderson made 10 more Rushmores (or whatever their favorite is), but it’s clear he’s not interested in doing that.

But when I look at the director of the past few years, I’m struck by how much Anderson’s works are profoundly concerned with the nature of filmmaking and storytelling in a way that rejects the notion of him simply retreating into his own stylistic quirks. The Phoenician Scheme is just the latest expression of Anderson working through these ideas. Yes, all the usual stylistic tics are present, but so are surreal, quasi-experimental flashes of what may be Zsa-Zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro)’s visions of the afterlife. These segments—which remind me of nothing so much as certain Andrei Tarkovsky scenes in Andrei Rublev (1966) or Mirror (1975)—unsettle the film in much the same way as the black-and-white scenes from Asteroid City do.

Scenes such as these challenge what we think of as part of the Wes Anderson style. But by not conforming to what is popularly understood as that style, they are, in a sense, ignored or not admitted into discussions of his evolving formal language. Maybe the problem is with audiences unwilling to admit that someone as formally distinct as Anderson can still develop meaningfully, even while working within the particular filmic language he’s developed over the past 29 years. As a recovering art historian, I’m reminded how someone like Michelangelo spent decades iterating on a stylistic language developed in his youth, though (as with Anderson) there are people who wish he hadn’t done so. They may think Pietà is where Michelangelo peaked, and he should’ve made a dozen more rather than exploring the range of his interests.

I’ll leave it there for the moment, though I will add that I’ve only seen the film once so far (sadly, at a Marcus theater with a misaligned projector). Anderson’s films have always rewarded repeat viewings for me. With any luck, I’ll be able to squeeze in another viewing before writing more. I’m keen to hear how you responded to this film: What, if anything, resonated for you? What’s been on your mind since seeing it?

Sara Batkie to David Boffa

re: “The Phoenician Scheme” and the (stylistic) gap

I appreciate your framing of The Phoenician Scheme as part of a stylistic evolution on Anderson’s part. I was one of those viewers who was slightly frustrated by some of the meta flights of fancy that The French Dispatch (2021) and Asteroid City took, despite liking both films to varying degrees. Part of what I enjoyed so much about this one is that it felt relatively straightforward by comparison. It really zipped along for me, and I laughed a lot as well. Though I wonder if some of that lightness of tone contributed to how some friends felt, which is essentially that it “didn’t add up to much.” I agree with you that I think it’s got some bigger things on its mind regarding capitalism and faith, but I also understand where those critical viewers are coming from. It actually reminded me a lot of when the Coen brothers made comedies together [editor’s note: the Coens are currently taking a break from collaborating]. I often found I needed to sit with those longer than their more dramatic films, and I think that’s the case with Phoenician Scheme too.

I wonder if part of the resistance just comes from how consistent Anderson has been. In some ways he’s spoiled us. When you think about it, he’s one of the few auteurs of his generation, save maybe his fellow Texan Richard Linklater, who hasn’t been sucked up into the Marvel or DC machines. He’s been able to develop an extremely recognizable style and, maybe even more remarkably, get original films funded. That’s not an inconsiderable accomplishment in the current cinematic landscape. While I don’t mean to suggest he should get some kind of “pass” from audiences, I’ve also seen jokey posts on Letterboxd and Bluesky about Anderson being trapped in a prison of his own making, and it kind of rankles me a bit. His deliberate filmmaking style isn’t something he needs to be saved from. If anything, his work is like a sandbox that we’re being invited to play in, and I’m pretty happy to be there.

Moving beyond that, what I found most enjoyable about the movie was Benicio del Toro’s central performance as Zsa-Zsa Korda. As far as father figures in the Anderson canon go, he affected me almost as much as Gene Hackman’s immortal Royal Tenenbaum. Anderson has made a few films about fathers throughout his career, but the focus has notably shifted since he became one himself. Earlier works like Tenenbaums and The Darjeeling Limited (2007) skew a bit more towards the children, and how they’ve been affected (usually adversely) by flawed parenting. Building on the Jason Schwartzman character in Asteroid City, Zsa-Zsa continues Anderson’s increased interest in paternity and what it means to be responsible for someone. He’s certainly not perfect at it, but there’s a reason his mantra is, “Myself, I feel very safe.” His give and take with newfound daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton) is genuinely touching, and reminded me a lot of my relationship with my own father (who, incidentally, took me to Tenenbaums when I was in high school.)

So I definitely feel like Anderson is stretching himself artistically and thematically, even within the supposed limits of his style. But how do you think the themes of The Phoenician Scheme fit into his work overall?

David Boffa to Sara Batkie

re: re: “The Phoenician Scheme” and the (stylistic) gap

I’ve been sitting with your question about how the themes of The Phoenician Scheme fit into Anderson’s work overall. The more I reflect on this film, the more I’m surprised at how thematically rich it is, especially given how relatively straightforward it felt compared to something like Asteroid City (as you noted). The particulars of the scheme itself are convoluted—rivet price manipulation? cousin marriage?—but, in general, the film does zip along with a pretty clear goal for our protagonists. It dragged a tiny bit during the opening meeting between Korda and his lone daughter Liesl as he’s laying out the plan and trying to convince her to leave her convent and take over his business (crossbow bolts notwithstanding); but otherwise things move quickly once they get started.

Despite this snappiness and the apparent simplicity of the plot, there is a thematic richness that is on par with almost any of his other films (with the possible exception of The Grand Budapest Hotel, which somehow manages to explore nostalgia, memory, desire, friendship, violence, decadence and decay, and more in its 100-minute runtime). It’s a father-daughter story, a tale of forgiveness and redemption, a critique (maybe?) of capitalism’s inherent exploitation and its ugly interactions with state power, and a meditation on faith. Not bad for well under two hours!

The most salient thematic element, and the easiest to fit within Anderson’s oeuvre, is that of fraught paternal relationships. Like you, I also loved Benicio del Toro as Zsa-Zsa Korda. I’m not sure he resonated with the same emotional weight as Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that changes for me in the coming months and years and on repeat viewings of the film. But more so than Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004) is the film that, to me, feels the most thematically linked from a father-child relationship standpoint. Both films deal with fathers who are ambitious to the point of neglecting their parental duties, and both are about the mending of parent-child relationships—or perhaps about forging such relationships where none existed before.

A key difference between them, and one that is related to your point of Anderson becoming a father, is which character is trying to build or repair the paternal relationship. In The Life Aquatic, the son seeks out the father; in The Phoenician Scheme, the father initiates these efforts. Anderson himself, in a recent episode of The Big Picture podcast, noted how he can mark moments in his life based on those moments’ relationships to the movie he was working on at the time. I think it’s reflected in the portrayal of Zsa-Zsa’s relationship with his daughter. While Zsa-Zsa reaches out to his daughter Liesl in part to ensure she carries on his financial and business legacy, he is also doing so following a near-death experience. By the film’s end, it’s pretty clear that his relationship with Liesl is more important than anything else. Admittedly, this didn’t really affect me emotionally during the viewing experience (maybe because I’m not a father? unless you count being a dog parent…), but it is something that’s becoming more impactful the more I reflect on it. What a beautiful way to end the film, with Zsa-Zsa and Liesl playing cards together, no? In some ways, it’s the most hopeful of father-child pairings we’ve ever seen from Anderson.

Forgiveness and redemption also feel particularly thematically relevant in this film. This isn’t the first time Anderson has dealt with such issues, but in The Phoenician Scheme he gives them the added weight of theological underpinnings. Apart from the film being set in various parts of “Phoenicia” (the Levant), the religious aspects are most obviously conveyed in two ways: via black-and-white scenes of the afterlife and through Liesl’s status as a novitiate in training to become a nun. The former are clearly doing more than just having fun with visual experimentation. These scenes ground the story in specific theological and even Biblical terms—and they provide the means of redemption.

Zsa-Zsa is, by all indications, not just amoral but also immoral: he is deceptive in business dealings, happy to exploit slave labor, and possibly responsible for the murder of several wives, including Liesl’s mother. That’s a lot to overcome from a redemption standpoint, but somehow he seems to have managed it by the end of the film: I’m oversimplifying a bit, but he has “changed his ways” (e.g., by paying his workers), found God (maybe), and repaired the relationship with his daughter. I know the movie (kinda) absolves him of Liesl’s mother’s death, but I’m not entirely certain we should believe that—Korba, after all, is the one who relays this information several times to Liesl as if trying to resolve his own guilt.

Zsa-Zsa’s moral arc is only possible because of the film’s grounding in Biblical, and specifically Christian, terms. (The idea that Wes Anderson of all people somehow snuck a faith-based movie into the indie-film world is a bit hilarious, now that I think about it.) Anderson seems to drive this point home in the hilarious cameo of Bill Murray as a bearded God, which could have been pulled straight out of a Renaissance painting. In the context of Christianity, this latter role can be read as a divine extension of the father-child relationship that Anderson so often explores: the god of the film is quite literally God the Father, the ultimate source of forgiveness and redemption (at least within a Christian context).

So, if I read The Phoenician Scheme as a faith-based movie, what a move, and what a rebuttal to the notion that he’s somehow stuck in an endless loop of self-parody. But I do wonder how seriously we should take those black-and-white scenes depicting the afterlife. Do they depict some sort of “real” afterlife, or are they just Korba’s dreams and imaginings of an afterlife that he believes in? And in the end, does it really matter if the source of Zsa-Zsa’s redemption is a God that exists only in his mind?

One last thing I’d like to mention, which has no immediate bearing on the above, is how much I enjoyed Michael Cera as the Norwegian entomologist Bjørn. This is my favorite role of his since he appeared in Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). I wasn’t quite sure where he fit into the film’s themes, but as our editor has helpfully pointed out, he’s primarily there as Zsa-Zsa’s counterpoint. And more importantly, Bjørn loves and accepts Leisl almost from the start (something Zsa-Zsa must come around to).

Where do you see this film fitting within Anderson’s works, thematically or otherwise? And what sort of space does it occupy in the Anderson canon? I’ve read several critics call it a “minor” work, even if they enjoyed it; but, as I’ve argued here, I’m not so sure I agree.

Sara Batkie to David Boffa

re: re: re: “The Phoenician Scheme” and the (stylistic) gap

I understand the impulse to label Phoenician a “minor” work, though I personally would hesitate to do so since Anderson is still actively making films. And what does “minor” mean in this context, anyway? The relatively linear plot might make it seem small-scale compared to something like The Grand Budapest Hotel, which I’d personally put in my top five of his films. But it also has one of his most sprawling casts traveling to far-flung “locations,” albeit clearly built on sound stages. There’s even, as you mention, a trip to the afterlife as Zsa-Zsa envisions it, which is not something I can recall Anderson doing before. His films have featured aliens and talking dogs, but they also generally stick to our mortal plane. Why he chose this particular story to make that leap isn’t something I’m prepared to answer confidently, though the fact that Zsa-Zsa shares a last name with legendary producer-director Alexander Korda might provide a clue.

The real-life Korda had ties to Powell and Pressburger, whose A Matter Of Life And Death (1946) is an obvious touchstone for Anderson here. In that romantic drama, pilot Peter David Carter (David Niven) walks up a literal stairway to Heaven. Another cinematic influence is Orson Welles’ Mr. Arkadian (1955), which is also about a wealthy tycoon who has a fraught relationship with his daughter. Benedict Cumberbatch, Zsa-Zsa Korda’s half-brother, who shows up fairly late in The Phoenician Scheme, is styled to look like Welles. In addition to these references, The Phoenician Scheme feels in conversation with everyone from Ingmar Bergman to Jean Renoir to Chuck Jones. It’s a dizzying amount of reference points, but as with anything Anderson touches, I don’t think it’s remotely random. They’re almost all from a period of filmmaking stretching from about 1939 to the late ’50s, when the Second World War loomed large in the culture.

While there isn’t a modern conflagration that Anderson is explicitly alluding to—not yet, anyway, though we’re possibly on the verge of one—I do believe he wants us to reflect on our collective nostalgia for that bygone era. Rampant industrialism may have had a more respectable veneer back then, as evidenced by Zsa-Zsa’s impeccable personal style. But it was still predatory, and that’s not something Anderson wants us to ignore even if his approach is more gently satirical and sympathetic than accusatory. He aligns with Zsa-Zsa, as he does with all the aesthetes in his filmography—a list that could conceivably include everyone from Max Fischer from Rushmore to M. Gustave from Grand Budapest Hotel to Mr. Fox of Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009). But Anderson also seeks to question the value of aestheticism in a society that’s often ugly. Gustave can’t stave off the barbarity of encroaching fascism. Fox is literally driven underground. And Zsa-Zsa, too, must find satisfaction in his failures.

That’s ultimately where I see The Phoenician Scheme fitting into Anderson’s work overall. In film after film, he’s made clear that he believes in the power of art on its own terms, and not as something that can save us but redeem us. They are two very different things. This is simply the most overt intertwining of his style with his intentions so far. For some fatigued audiences, it might be more of the same. But for me, and I gather for you as well, David, it’s another step forward in the career of an artist who has continually refused to compromise his vision. We’re lucky viewers for it.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.