Bats in the bedroom

Spooky season coincides with increased human-bat encounters.

Around 3 a.m. on Labor Day, Sara Woolery was awakened by her cats running around her bedroom.

“The cats were racing around the bedroom, leaping on and off the bed, which sort of disturbed my sleep, but didn’t wake me up fully. And then one of the cats stopped at the base of my feet and was just turning in really tight circles over and over again,” Woolery says. “That woke me up.”

Worried something was wrong with the cat, she got up, went to it and “was like, ‘Luna, what’s going on? Are you okay?’ And she’s still turning tight circles over and over again.” Woolery then realized the cat was tracking something in the bedroom. She turned on the light and saw a bat flying in circles around her bed.

“So, I panicked a little bit,” she says. “I think the bat was a lot more freaked out than I was, but it was still like… when you get woken up at 3 a.m. you’re plunged into semi-crisis mode.” [Full disclosure, Woolery and I work together at a bakery, which is how I heard this story.]

Morgan Pike, communications coordinator at Public Health Madison and Dane County (PHMDC), tells Tone Madison in an email that PHMDC animal services team says there was “an uptick in ER visits for potential bat-human exposures in August [and] September, but that is expected this time of year.”

“Mid-August is usually the peak time for bat activity and possible exposures,” Pike writes. “It coincides with increased bat activity, as bats are migrating and getting ready for hibernation. This is also when bat pups are learning to fly.”

“It’s at that point where they start to not only learn how to fly on their own, forage on their own, and then explore everything that there is to offer, not only in the roost itself, but outside,” says Paul White, a mammal ecology who specializes in bats at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR). “And so that’s when they will slip into places.”

Woolery grabbed her cats and left the bedroom, careful to shut the door behind her. Her partner, a night owl, was still awake downstairs. Woolery recalls they discussed whether to try to trap the bat to test for rabies, but the main question was how. Also, if they trapped the bat and sent it in for rabies testing, it would be killed. Considering that and the fact that it was still 3 a.m., Woolery decided to just let the bat go.

“I feel like the bat’s had a hard time,” she says. “It’s not the bat’s fault.”

She went back into the bedroom, opened a window, removed the screen, shut the door, and left to go sleep elsewhere, hoping the bat would find its way back outside.

“I kept telling myself that I’m not afraid of bats, because I’m normally not,” she says. “They’re just a little freaky when they’re flying really fast around your bedroom.”

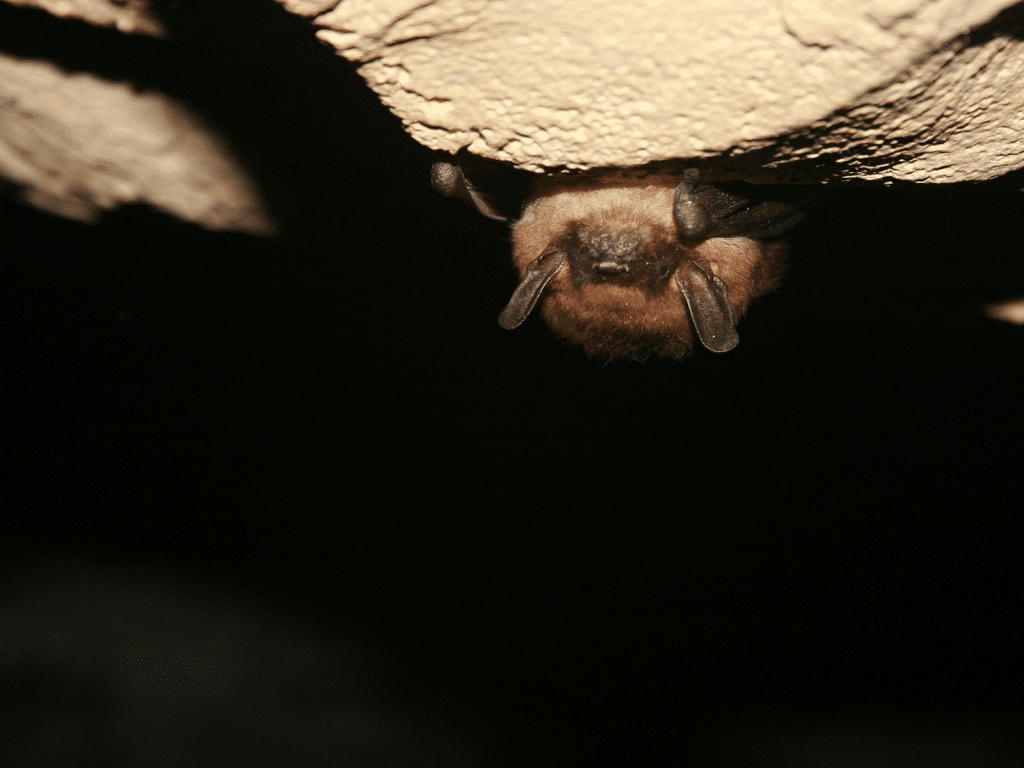

Wisconsin has six bat species, but only two are likely to come into close contact with humans—the little brown bat and the big brown bat. Little brown bats tend to hibernate in caves, mines, and other similar sites. If you encounter a bat in a house, barn, Bascom Music Hall (during Tone Madison Music Editor Steven Spoerl’s talk with the authors of Songs For Other People’s Weddings for the Wisconsin Book Festival), or a bat house, odds are it’s a big brown bat.

Unlike other animals known for getting into people’s homes, White says big brown bats, which typically eat insects, don’t have the jaw strength to gnaw their way into openings. But they can slip into openings as big as a half inch or greater, which in older homes—like Woolery’s East Side home, which was built in 1929—are more common than residents may realize. Older homes may have small gaps along their rooflines, or where their rooflines intersect with chimneys and vents, that bats can get into fairly easily.

White says the DNR typically sees another uptick in potential human-bat encounters in the lead-up to the Christmas season.

“Because they’re, in many cases, hibernating, and they’re in these dark recesses of homes, basements, crawl spaces, attics, that type of thing, that are not often visited,” White says. “And then only when holiday decorations are put up or taken down, is when people might actually find them.”

If you do find a bat in your home, Finke emphasized that you should “never touch it with your hands.” If you do want to try to catch it, she recommends using a plastic tub and piece of cardboard. Or you could contact PHMDC’s Animal Services department for help.

When Woolery woke up the next morning, the bat had left her bedroom (and been replaced by hoards of mosquitos, which was a whole other issue). She did some research online and learned that, because she was sleeping when she encountered the bat, public health offices recommend getting the Rabies Post Exposure Prophylaxis (RPEP), a series shots that include the rabies vaccine and, if the person has never been vaccinated for rabies before, human rabies immune globulin (HRIG). HRIG is made from antibodies against the rabies virus and protects the body from infection in the time it takes the body to make its own antibodies.

The county or state doesn’t have great data on how many bat-human encounters happen or the circumstances of those encounters, but one reason may be that bats are not a major threat to humans. White cites research that found 1% of the wild bat population carries rabies at any given time, but with bats that are flying around homes or other indoor spaces, “it is those bats that are acting odd, un-bat-like, right?—those are the ones that are concerning.” While Woolery thought it was unlikely the bat had bitten her, she decided not to take the risk and to get the RPEP. Rabies is extremely deadly, and by the time symptoms are present, it’s probably too far along to treat. Another indicator of the uptick in human-bat encounters: the UW Health clinic closest to her told Woolery they didn’t have enough of RPEP and she had to go to another clinic.

A UW Health representative tells Tone Madison in an email, “I checked into this with our pharmacy team, and we have an appropriate supply of rabies vaccine shots on hand.”

“Lots of people told me, when I was like, ‘Do I really need to go get a rabies vaccine?’ They’re like, ‘Yes, you should just go get one,'” Woolery says. “I told the story to a lot of people, they were like, ‘Oh, bats used to come in my college house all the time, and nobody ever said anything about getting rabies vaccines.’ So I feel like that awareness has changed.”

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.