Andrew Fitzpatrick’s “Forest Calendar” emphasizes an inevitable cycle

The experimental musician talks us through his latest album and his Observatory series at Gamma Ray Bar.

The experimental musician talks us through his latest album and his Observatory series at Gamma Ray Bar.

On “Wall Koy,” the opening track from Andrew Fitzpatrick‘s new album, Forest Calendar, a remorseless cascade of dread acts as a weighted blanket. Before that blanket becomes too suffocating or too restrictive, a lush synth figure pokes through the knitting to offer proof of lightness as a reprieve. There is a pattern. A structure. Over the course of Forest Calendar, Fitzpatrick meticulously expands upon this dynamic.

In its first half, the album goes heavy on attack—an upward ascent of volume granted to an individual noise. In its second half, an elegiac focus on decay—a descent of volume—takes precedence. But there is still balance; Forest Calendar, in its essence, is a reflection of our own mortality and the cyclical nature of life. Even the phrase “forest calendar” suggests an ongoing loop of irrepressible beginnings and inevitable endings.

Fitzpatrick’s name should be familiar to regular Tone Madison readers, or anyone who enjoys experimental, electronic, or genre-subverting music from Wisconsin artists. He’s a current, former, or auxiliary member of Bon Iver, Volcano Choir, All Tiny Creatures, Cap Alan, Azha, and Friend (a new duo with Milwaukee-based experimental percussionist Jon Mueller), among others. Fitzpatrick has also been featured in occasional live collaborations with a number of acts, including Spiral Joy Band and Spires That In The Sunset Rise. Additionally, he’s released a sweeping array of solo work (as Noxroy and under his own name). Fitzpatrick runs lead programming for the ongoing Observatory: A Night Of Experimental Musics series on select Wednesdays at Gamma Ray Bar, and has continually deepened his own musical explorations of experimental synthesis and processed electric guitar.

Fitzpatrick draws upon all that versatility and variety in his highly improvisational solo work, which relies heavily on his intuition, deep understanding of craft, and conviction. Forest Calendar presents those qualities in an enticing package that manages to communicate a number of ideas to listeners on both micro and macro levels. There is a seemingly unavoidable narrative at play on the album—but a poignant blend of small, emotional moments on Forest Calendar goes a long way in proving the coloring is as important as the full picture.

The Amsterdam-based boutique ambient label Shimmering Moods saw something in Forest Calendar, and ultimately agreed to put out the record after Fitzpatrick floated it their way. Label head Paul—who goes by first name only—has a long and well-documented history of finding fascinating, little-known ambient, experimental, and electronic works. Forest Calendar becomes the latest in his extensive, ongoing tally. Even in this relationship, a striking reflection of an implicit relationship emerges. Shimmering Moods, Fitzpatrick, and Forest Calendar all come across as diamonds in the rough. Together, they represent a few distinct, singular visions finding purchase at a fascinating intersection of bold exploration and avant-garde impulse.

Fortunately, Forest Calendar is more than up to the task of rewarding the type of intensive scrutiny that accompanies serious investment. From the abrasive scraping and haunting whispers that cut through “Wall Koy,” to the nightmarish evolutions of those qualities in “Bat Oath,” to the unmistakable sense of disintegration embedded into “Holidays,” Fitzpatrick gives listeners a huge swath of minutiae to cling to, dissect, and consider.

Occasionally, the effect can feel a touch overwhelming. This is especially true for “Peal,” which bristles with the gentle anticipation of a violent impending storm, bringing to mind David Wingo’s score for the 2011 film Take Shelter. The track conjures images of reeds swaying in the wind, a treeline trembling in the distance, and the deliberate rippling of a slowly-forming puddle being pelted with an emergent rain. “Peal” is a masterful instance of composition, striking a balance between immediate satisfaction and long-lasting impact.

By the time Forest Calendar reaches its concluding arc—”Everglades,” “Holidays,” and “Cardinal“—the music sounds as if it’s struggling to remain intact. Buried within the decaying audio patterns is a sense of actual decay; the implicit forest established in the album’s first half now thoroughly ravaged by the brutal storm “Peal” suggested was imminent. Over that closing trio of tracks, relative silence becomes a sledgehammer. Everything becomes sharper and more staccato, and there is an absence of steady sustain. Whatever life remains in this environment now struggles to push back against a new reality. Tape hiss becomes the chirping of birds, percussive scraping becomes the frenzy of animals scavenging a barren land of ruin. But those noises also convey the possibility for new life to spring up and overtake a bleakly-rendered landscape. “Cardinal,” especially, suggests a lush overgrowth, even as an insistent death rattle dominates the track, before finally abruptly giving way in the album’s final seconds.

Forest Calendar tells a story, but it’s a narrative that Fitzpatrick insists came after the fact, while still admitting that the work does represent a journey. He never intended to foreground a grand scope of birth, death, and rebirth. All of it came about as a manifestation of the musician chasing his own artistic impulses, and following through on finalization. Whether an intentional narrative or unintentional journey, Forest Calendar represents one of the most vivid and thoughtful experimental ambient albums to come out of Madison this decade. It’s a trip worth taking.

Fitzpatrick sat down with Tone Madison in mid-February for a video call to discuss narrative, improvisation, Forest Calendar, navigating impulse, and the Observatory series.

The next Observatory show is Wednesday, March 5. Leechhawk and the Blair Fitzpatrick Russell Trio (Matt Blair, Andrew Fitzpatrick, and Tim Russell) are the performing acts.

Tone Madison: Let’s start at the end. When and how did you know Forest Calendar was complete?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: Well, I think early on in the pandemic, I undertook a much-needed organization effort. I use Logic for all my recordings, so all of my Logic recordings—which were just not really organized—there’s that massive list of [tracks with names like], “Resident equalizer with high pass filter one.” I finally had the time to go through and organize things that made sense together. I would say it was sometime in the summer of last year, spring or summer. I felt like it was a cohesive and final project.

It seemed like it was as far as I could go with those tracks, because there’s nine of them. I have an enormous amount of recordings that are kind of like in various stages of completion, like a lot of people. I realized after that organization effort that I have more than I kind of know what to do with, in a lot of ways. Those [Forest Calendar tracks] made sense together. My first release, my first solo release, was just basically guitar—treated, processed guitar—which, I keep wanting to do another one of those. [It’s] just a matter of finding the time to put finishing touches on things.

Tone Madison: Can you take us through your construction and composition process for the tracks for Forest Calendar?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: I didn’t use any guitar on this. Sometimes I’ll use barely any guitar. But I feel like I still need to mention that I use guitar. With the electronics world, especially, I use a lot of modular synthesis. There’s always different configurations of modules leading to discovery. I’m kind of trying to go through looking at [prior recordings]. Another problem is that I named the pieces pretty late in the process. So [I didn’t have things neatly ordered for] some of them.

For a lot of them, I don’t have a really, really deep connection with the name of the piece. For example, “Cardinal” is a recording of a laminator. Just a 3M Scotch laminator. My son was in this room over here in the basement, and it had this, well, there’s definitely some treating of the sound, but the basic sound—the laminator—is pretty present. But there’s also this whooshing sound. That’s the processed version of this, like, automatic rocking bassinet thing that we had. It was paired with the laminator in an interesting way. And I use a lot of computer processing.

I went back, revisited it probably sometime last year, and added a couple more layers. I’ve been using this re-synthesis process over the last couple of years. That’s been exciting for me. Running audio, just basically any audio, through this module that resynthesizes the incoming audio into a kind of limitless array of [noises]. You can really shape it into a lot of different forms. I’ve literally been enjoying just kind of re-re-amping, or re-synthesizing, or just synthesizing sounds through that. There’s a little bit of that that happened [on Forest Calendar‘s tracks]. But a lot of them are, for the most part, I would say either starting with some sort of synthesizer patch. Sometimes that involves a field recording that’s being processed within that patch. So there’s straight synthesis, and that leads to the end product.

Some of it’s recordings of, like, ice cracking and like snow. I mean, there’s so many. I believe I’m using some [recordings that] I’ve probably used several times at this point. [There’s] this recording I made in Spain with these birds that were flying really close to where I was on this rooftop, and then there’s some bells going, like a church bell, and the town courtyard. There’s at least one that has some birds on it. I’ll set up, usually, something [with] the synthesizer and record a chunk of that, and then revisit it and do some editing and embellishing. But this one was a lot of synthesizer, a lot of processor processing in the computer. Different plugins and software, I would say that for the most part.

Tone Madison: Was that experience with “Cardinal” emblematic of the overall approach to the songs on Forest Calendar? Where they were just worked on incrementally over time?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: That’s, in general, how I work. I’ll kind of construct a scenario, based on an idea. Or [I’ll be] experimenting, and document that. There was something I recorded, I think it was yesterday or two days ago, actually, that I was just like, “Oh, I haven’t messed with this module for a while.” And then that turned into two hours of trying to finish [a] three minute piece or whatever. Usually, that’s not necessarily the case. I’ll have the documented improvisation, like the live improvisation that I record, and then revisit it [when] I’m excited about it, maybe. But, [considering] life circumstances, it’s hard for me to dig in and spend hours and hours on something. It’s usually these piecemeal chunks of time trying to finish stuff.

Tone Madison: When music is explicitly improvisational, it can often be difficult to tell when a track’s complete. Did you have to fight your instincts at any point to continue minimizing or maximizing from track to track?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: I am always kind of wrestling with that. “Should I just leave it alone? Like, it needs this [tweak]. I could add this lower frequency, or in this part, I need to take 400 hertz or whatever out of here. Or I need to do some sort of… yeah, it definitely needs something.” It seems like after I record an improvisation, I don’t know what else to add to that. But that seems to be rare for me. I am never really quite satisfied, even when something’s like done.

I guess it’s a matter of time, and the amount of time on my hands. I could drive myself nuts trying to [be], like, “What is the ultimate version of this?” I’m trying to let go of the more critical aspects of my psyche, where I’m trying to be happier with what’s true to the original performance. Like the thing that I was recording a couple days ago, just following the whim or the urge to [go] “I’m gonna do this.” I’m just recording now. Just doing it, and trying not to overthink it. [Laughs.] But I’m always overthinking things in general. I’m trying to be a little healthier about that when it comes to music, especially considering how much stuff, how much recorded stuff, I’ve amassed on hard drives.

Tone Madison: So much of Forest Calendar feels akin to score work. When creating, do you take visuality into account, or does the inspiration or decision-making stem from an audio-based emotional or intellectual impulse?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: I think it is a blend of both. I don’t think I’m necessarily conscious of it, but it’s interesting. I’m thinking of some of the noisier tracks on this where it’s not, like, harsh noise. Well, maybe it is harsh noise. That’s all relative, I guess.

It’s not something I really think about, necessarily. But there is a visceral [quality] when there’s something that’s maybe more static, that can lend itself to some sort of [visual]. The sky in general, weather, whatever. Clouds or stars. But then also, like, something where there’s lots of things happening, fast, and there’s different sounds happening? That could definitely almost fully work. Or something where there could be some sort of, like, 3D or 4D object that’s morphing. And that brings up the idea of psychedelic music. I appreciate the psychedelic music descriptor, even though it’s never really used in the right context, like Jefferson Airplane.

I mean, they were a band that came about in the psychedelic era. It’s rock and roll music, ultimately, but there’s something [there]. Like the Brian Eno ambient stuff, or just any number of music like that, or David Behrman electronic. He’s someone that, like, I don’t really see it described as psychedelic music much, but it’s stuff that I feel like the pure definition of like mind-manifesting psychedelic. Where it definitely has the ability to conjure images.

Almost 10 years ago, I scored several Norman McLaren films for the Eaux Claires festival. And I can’t say that I necessarily learned from that. It seemed like my sound-making process sort of naturally worked with certain films where there were these balls or objects, different shapes going across the screen. I was doing, in some instances, very literal, like, “Oh, when this thing appears, [a certain noise] goes away. Doing [that] frame by frame, kind of. But I guess ultimately, it is like a combination where there’s a little bit of intuition, where it’s just kind of like, “Oh, these sounds work together.” But sometimes it does relate more to an image-based thing. Those approaches go back and forth, it seems.

Tone Madison: To a similar end, when you’re improvising, are you approaching that improvisation with a narrative framework in mind? Or are you relying on an emergence of potential narrative? Or does narrative construct hold less weight than other artistic considerations?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: I don’t devalue the idea of having a narrative. If I wrote more traditional songs—which I have done, but not for a while—I take that more into consideration. There’s more planning involved, I guess. With the solo stuff I do, without really thinking about it, it’s very much improvisation in the moment. Ultimately, something starts from the first track. Like, I just happened into this sound, and immediately it [clicked]. It’s usually an intuition thing. Going back to that first piece, it definitely suggested, immediately, some things, so then I followed that lead.

The narrative kind of comes into play after the fact. Like the laminator thing. That was just starting with,”Oh, that is an insane sound.” Instead of my [usual setup at that time, I used] these mics I had just gotten for really close-up recording. So like, good opportunity to use those. And [I] got the file into the computer and built from there. That’s, in general, how I work. Because improvisation is where it all comes from. Every piece that I have comes from improvisation at some base level.

Tone Madison: Forest Calendar seems to be structured in distinct halves. The first half establishes a commitment to attack and the second half foregrounds decay. Was that a sonic template-based decision or a broader narrative one?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: I don’t know if there’s a template so much, but it is the narrative. The narrative definitely is suggested after the fact. I wrestled with how to sequence the album, and there were different ways I would maybe not have done so much front-loaded attack on it. Because I feel like maybe it’s a little bit too much of an attack. Not to be cliché, [but] it’s sort of a journey. Constructing a journey after the fact with, like, “I know these are what I want to be on the album.” Going through, even though it is front-loaded with attack, I think it still does make sense. But it makes me think. I have a couple different next-album ideas, maybe in reaction to [Forest Calendar].

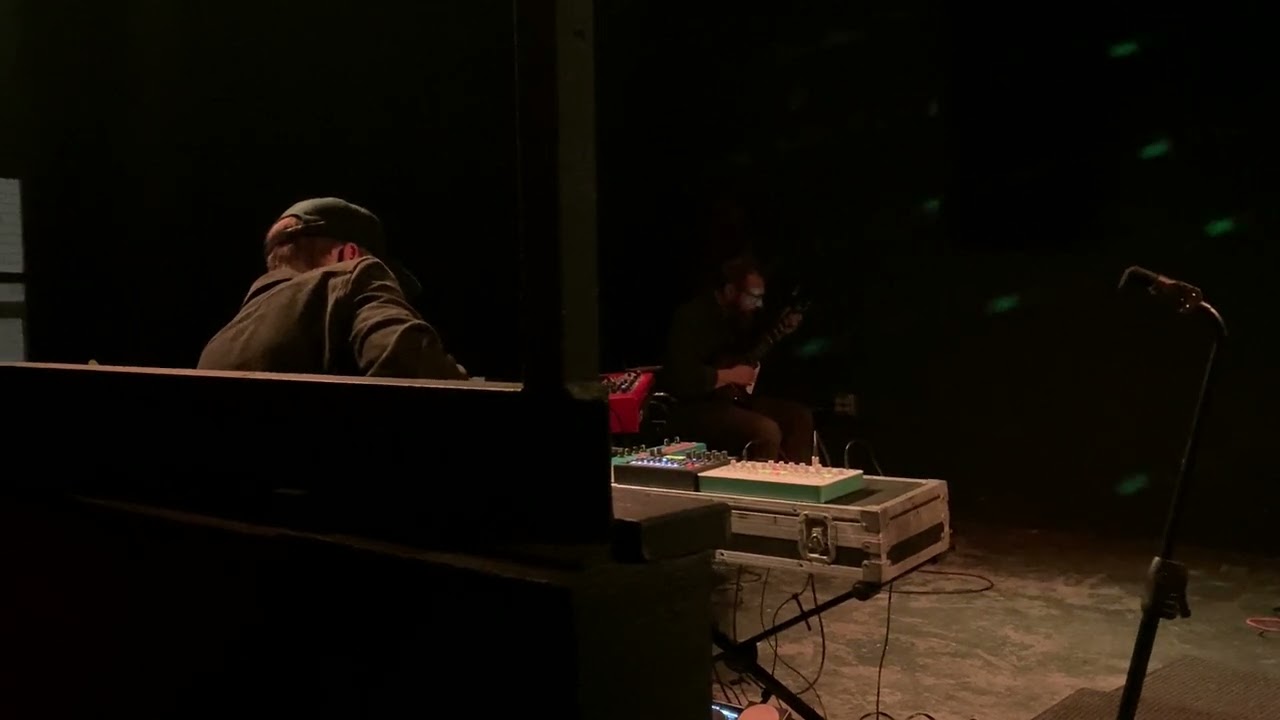

Tone Madison: When you’re not writing or performing music, you’ve been programming the Observatory series at Gamma Ray Bar. How did that come about, and what do you feel like the series is accomplishing as it progresses?

Andrew Fitzpatrick: That came about the first time I went to Gamma Ray. I was playing a show with All Tiny Creatures, Collections Of Colonies Of Bees, and The Mossmen. That was, gosh, August or September. I can’t remember when that was, but [Gamma Ray owner] Kevin [Willmott II] was like, “Hey, man, I want you to book the series we’ve started, kind of, over the course of the evening.” He picked my brain a little bit, and I was definitely hesitant initially. I don’t really consider myself [to be] great at promoting in general, but the ideas that he tossed out… As I thought about it, like, it could be interesting. It was a good opportunity, because, with Bon Iver not really playing live for the foreseeable future, it opened up a much larger space of my life that was devoted to playing music. [That space was] opened up again. So this has been a good opportunity, selfishly, for me to connect with some different collaborations that have been in different levels of dormancy or hybrid hibernation. Or that we’re active. And it’s just like, hey, good opportunity to do this.

But also Kevin, really wanting to bring something different to downtown. I mean, you know what’s up with Gamma Ray and not being Live Nation, etc. Having something, because it’s a little earlier, and, I guess we started in September or October? I think it was November, actually. So we haven’t really had any warm months for this yet, but I think he’s hoping once spring or summer rolls around, there might be some foot traffic. Like, “Oh, what’s going on here?” But [we’re] really trying to bring something different downtown. And Kevin’s [been extremely supportive].

It’s been really cool to [know] there’s places [that will be that supportive]. Madison has gone through cycles of having places where experimental music can happen, and right now, it’s pretty decent, right? But I think for playing at a bar through a really—not that it needs to be a bar—but [a small to mid-size venue that] has a really nice system, and the opportunity to be able to play through that [is great]. And he was really into the idea of collaboration happening too. We’re trying to make that a part of the night, for the most part. Like, two sets and then a collaboration between the two different acts. We’re still tweaking the format a bit. We were doing twice a month. We’re gonna start doing it once a month.

But I think that is something that should happen more often. I [was] inspired by the All The Sounds Are Done series that’s been happening at Communication. I haven’t been able to do it for the last handful of months, but starting in September of 2023, I attended several of them in a row. That was the first time that I had been able to do [or] even knew [of] anything like that existing. I grew up in La Crosse. There’s so many, like, blues open jams, but it’s like blues jam at a bar. And that’s a different thing. This, what they are doing, the way they have it set up, just… like, with Bon Iver coming off the road, now I’m going to be in Madison more. And I feel, all of a sudden, like I haven’t spent much time here. I feel sort of disconnected. And that was the first time feeling like, “Oh man, like, open things up,” as far as just like, “Oh, there’s people.”

I mean, I always know there’s people playing music around. But it’s cool to know that there’s people [who are] into exploring. I’m trying to broaden my net, too, because I know there’s people out there that I’m probably overlooking, that I hope I am not for much longer. But it’s been cool to see people regularly showing up, and people seem to be generally, genuinely appreciative. Not that I’m fishing for it at all, but people seem to be like, “Oh, this is awesome [to] have something like this.” It’s been cool.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.