A new Wisconsin law undermines the transparency pitch for police body cameras

Act 253 contradicts open-records norms, and now it’s time for law enforcement to put it to use.

Act 253 contradicts open-records norms, and now it’s time for law enforcement to put it to use.

A new Wisconsin law could provide an easy out for law enforcement agencies who pledged that the adoption of body-worn cameras would bring greater transparency, accountability, and trust.

The Republican-controlled Wisconsin Legislature passed the measure, which allows law enforcement agencies to charge public records requesters for the cost of redacting video or audio material, in early 2024. The State Senate passed 2023 Wisconsin Act 253/Senate Bill 789, in January on a largely party-line vote (one Republican, District 11 Sen. Steve Nass, voted against it, and one Democrat, District 22 Sen. Bob Wirch, voted for it). The law then cleared the Assembly in February with near-universal support, on a 94-3 vote. Democratic Governor Tony Evers signed it into law on March 29.

This is the first time in Wisconsin’s history that state open-records laws have embraced redaction fees.

There are a few exceptions—namely for requesters who agree to provide “written certification to the authority that the requester will not use the audio or video content for financial gain.”

In another first for Wisconsin public-records laws, Act 253 gives authorities a way to punish records requesters—providing for a $10,000 fine if a records requester is deemed to have sought an exemption from the redaction fees under false pretenses.

The law, which drew the opposition of the open-records advocates at the Wisconsin Freedom of Information Council, media-industry groups including the Wisconsin Newspaper Association and the Wisconsin State Journal editorial board, and the ACLU of Wisconsin, is vague enough that it could intimidate or hinder a wide variety of public-records requesters—including journalists, or anyone else whom law enforcement agencies could accuse of making money from public records.

Just weeks after Act 253 became law, the Madison Police Department (MPD) launched a long-awaited body camera pilot program in its North District (which encompasses a large area of the north and east sides). The Dane County Sheriff’s Office (DCSO) is planning to launch its own pilot program later this year.

A new law untested in Dane County, or anywhere else

The UW-Madison Police Department (UWPD), which adopted body cameras in 2015, has already begun using the law to charge redaction fees, making no exception for journalistic inquiries—as Tone Madison discovered when a freelance contributor filed an open-records request for body camera footage in late May.

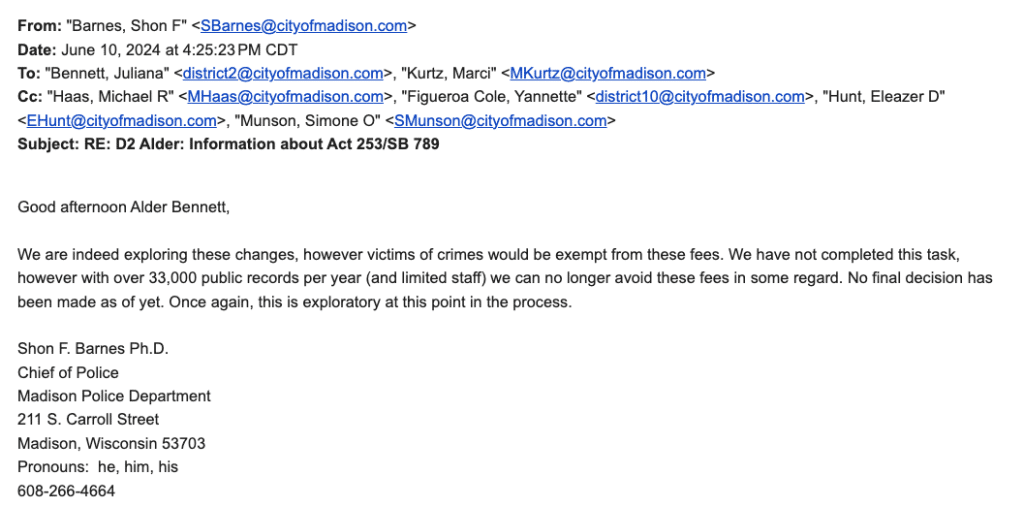

MPD, meanwhile, has not yet implemented Act 253, in part because Madison’s city-level open records ordinance explicitly prohibits redaction fees. Judging from comments MPD Chief Shon Barnes made in a June 10 email to District 2 Alder Juliana Bennett, the department is considering ways to get around that obstacle:

We are indeed exploring these changes, however victims of crimes would be exempt from these fees. We have not completed this task, however with over 33,000 public records per year (and limited staff) we can no longer avoid these fees in some regard. No final decision has been made as of yet. Once again, this is exploratory at this point in the process.

Act 253 provides an exemption “if the requester is an individual directly involved in the event to which the requested records relate,” meaning crime victims are already exempted from fees under the new law.

Barnes did not reply to Tone Madison‘s request for comment for this story.

(MPD spokesperson Stephanie Fryer was more circumspect in a June 11 email to Tone Madison: “We are reviewing and discussing our practices, but nothing is imminently changing.”)

Bennett is one of the most vocal critics of police on the Madison Common Council, but says Act 253 wasn’t on her radar until earlier this month.

“I am concerned with the very clear barriers to equity, accountability, and transparency should MPD use this policy,” Bennett says. “I would ask Chief Barnes and MPD to consider and respond to those issues with an alternative plan that did not play upon existing structures of inequality.”

District 8 Alder MGR Govindarajan says he hasn’t heard anything from MPD about these potential changes, but also opposes redaction fees. (Govindarajan is a UW-Madison student and his district encompasses the campus, though as a city official he doesn’t have any authority over UWPD.)

“Wisconsin’s Open Records laws are there to promote transparency. Allowing agencies to require a fee for redactions—something the requester has no control over—goes directly against transparency,” Govindarajan says. “I would hope to see agencies drop any fee requirement associated with redactions, especially if they are related to the press, which should have a right to this information.”

DCSO is at an even earlier stage in its own adoption of body cameras, and has yet to decide how to deal with the new law.

Dane County’s ordinances don’t mention redaction fees one way or another, because state law has never explicitly authorized them before; a spokesperson for the Sheriff’s office tells Tone Madison the county has not yet developed a policy on redaction fees.

A carve-out from a “presumption of complete public access”

The implications of Act 253, a novel law in Wisconsin’s history and one that cuts against US public records norms, are potentially vast. It’s an outlier in Chapter 19, Subchapter II of the Wisconsin Statutes, where most of our state’s open-records protections live, which declares that its open-records provisions “shall be construed in every instance with a presumption of complete public access.”

But now Act 253 is tucked right in there, explicitly spelling out instances where that presumption doesn’t hold.

Before the passage of Act 253, state law allowed government agencies to charge fees for a few specific tasks like copying, mailing, or transcribing a record. (For instance, if you file a records request with a City of Madison department, city staff will often put the files on a thumb drive and charge you a few bucks for the cost of the drive.)

Police went to bat for Act 253 precisely because it’s a departure from the norms of Chapter 19.

The new law is a direct response to the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling in a dispute between the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, which was seeking records from the Milwaukee Police Department, and the City of Milwaukee, which wanted to charge more than $3,000 for the labor cost of redacting the requested police reports.

The newspaper sued, and the court—otherwise bitterly divided—held unanimously that Chapter 19 did not allow government agencies to charge redaction fees.

To get around this ruling would require an act of the Legislature.

From the federal Freedom of Information Act on down to most state and local records laws, the prevailing norm is that the government cannot and should not obstruct an open-records request based on the motives of the requester. The why of it is just not supposed to matter: The government can withhold or redact records for any number of other reasons. But generally speaking, if it can release a record, then that record belongs to everyone. The government can’t dictate how people use it once it’s out in the open. A public record is not private intellectual property.

The new law’s provisions around “financial gain” invite police agencies to assess the motives of people seeking body camera footage, and what they are likely to do with it, then decide whether or not to charge those people redaction fees. Longtime Madison journalist and Wisconsin Freedom of Information Council President Bill Lueders summed up just how unusual this is in a February statement opposing the new law: “The bill does not state who decides whether a particular use constitutes forbidden financial gain or on what basis it would be decided. Either way, the provision disregards one of the fundamental principles of the state’s Open Records Law—that it should not matter who is seeking a given record or why.”

Act 253 does provide some exemptions, mainly for people who pledge not to use the records for “financial gain,” records related to “a shooting involving an officer of a law enforcement agency,” and (again) people who are “directly involved” in an incident related to the records. And the “financial gain” provision exempts people who might seek to gain money in the form of damages from a civil suit—meaning the law does not impact people seeking video or audio material to use in court.

Instead, it specifically impacts people seeking records through open-records requests—including members of the media, activists, or any curious member of the public.

Legislation by and for police

Drafted and co-sponsored by a cohort of former law enforcement officers in the state legislature, the legislation quickly earned the support of all of the state’s major police unions and police advocacy organizations, which lobbied in support of the bill.

One of the bill’s main authors, Republican District 23 Sen. Jesse James, currently works part-time as a police officer in the Chippewa County village of Cadott, and previously served as the chief of police in Altoona. Several of the other Republican legislators who authored or co-sponsored the bill are former police officers, including District 21 Sen. Van Wanggaard, District 86 Rep. John Spiros, and District 72 Rep. Scott Krug. Another, District 18 Sen. Dan Feyen, has a legislative district office in—get this—the lobby of the Fond du Lac Police Department. The text of the bill doesn’t mention body cameras specifically, but proponents of the bill complained that public requests for body-cam footage cost too much and eat up too much staff time.

These complaints match a familiar pattern that has played out all over the country. Police departments have been adopting body cameras at a rapid clip over the past decade. Chiefs and sheriffs often lead the charge for these programs, lobbying for funds and promising that cameras will increase transparency, accountability, and community trust.

But once people start asking for the resulting video, those very same police leaders balk at the financial and PR implications of releasing it.

For instance, Wisconsin’s largest police union, the Wisconsin Professional Police Association (WPPA), has vocally advocated for body cameras—and for the law restricting public access to body-camera footage. WPPA executive director Jim Palmer urged Madison to pick up the pace on MPD’s body camera pilot after the Common Council allocated funding for it, asking Capital Times reporter Allison Garfield in a February 2023 article: “How much is the public trust worth? It’s hard to put a dollar amount on that.” The transparency and trust fostered by such a program, as Palmer presented it then, would outweigh the potential costs.

Palmer must have rediscovered his frugality when Act 253 was working its way through the Legislature. In a January 2024 interview with Milwaukee public-radio station WUWM, he defended the idea of charging redaction fees: “There are some extraordinary costs associated with fulfilling public-records requests when it comes to body-worn camera video evidence. I think it’s important for agencies to be able to recoup some of that.”

The American public has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on body cameras but seen very little body camera footage, as ProPublica found in two investigative stories published in December 2023. Some police agencies around the country have claimed that they can’t release body camera footage at all, or have tried to evade public scrutiny by claiming that all the footage is evidence, rather than public record. The resulting thicket of new policies has weakened the already toothless, if well-intentioned, body of American open-records law.

At best, this represents short-sighted policymaking: Police didn’t prepare for the implications of generating thousands upon thousands of hours of footage that could be subject to open-records requests, even though they asked for this problem. At worst, it’s a bait-and-switch: Body cameras may or may not deliver greater transparency, but the sunk costs give police additional leverage to demand more funding and staffing.

Either way, it begs the question of why police didn’t factor in these downstream costs when pushing for body-camera funding in the first place. If they couldn’t put a dollar amount on public trust, why not ask for adequate resources to process footage for public release? It’s not surprising to see a bit of a mismatch at MPD or DCSO, departments just getting started with body cameras. But UWPD has used body cameras for nine years, and still has limited staff devoted to this downstream work. “We have two people who work on records requests,” says UWPD spokesperson Marc Lovicott. “Our Professional Standards Lieutenant oversees them, but the two staffers are the main ones who work on requests. To share an example of their workload, they responded to 831 public records requests last year and 777 requests in 2022.”

Wisconsin’s redaction-fee law has been on the books for less than three months. It consists of about 400 words and relies on broad terminology. It has not yet been tested in court. Police around Wisconsin looking to implement the law have received no legal guidance from the Wisconsin Department of Justice. In this new and uncertain landscape, Wisconsin police have even more latitude than before to obstruct access to body camera footage by charging prohibitively expensive fees or interpreting the law as favorably as possible. Anyone who’s sought a lot of public records—journalists, activists, attorneys, obsessively curious citizens—knows that government officials will often apply open-records law incorrectly, or sometimes just brazenly disregard it. Unless you have the means to sue, you have little recourse. Police have even more strategies to block transparency, like the selectively applied “open investigation” gambit. This new law hands another blank check to people who already have a tall stack of them.

“We’ve seen across the country that there’s a number of different justifications that law enforcement use to hide audio and video footage,” says Amanda Merkwae, Advocacy Director at the ACLU of Wisconsin (which lobbied against Act 253, as did the Wisconsin Newspaper Association). “One of the ways that that footage can be hidden is by making it available only at a cost-prohibitive fee, or using different justifications to hide release of the footage as long as possible. When police are given the discretion to publicly release favorable body camera footage but withhold negative footage using whatever justification they’re using, police body cameras essentially become nothing more than a police propaganda tool.”

Police understand that high fees can dissuade members of the public from seeking records. Sometimes they even admit it in emails that are, themselves, public records, as a detective at the Wauwatosa Police Department did in 2016. The current and former cops who supported Act 253 were not so blunt. In written testimony submitted to a legislative committee, Rep. Spiros wrote that “Senate Bill 789 does not change access to public records that are currently available under the open records laws.” Written testimony from the Wisconsin Chiefs of Police Association hit this talking point twice, stating “This proposal makes no other changes to the current statutorily defined open records process and does not impact access to records,” and later, “This legislation does not impact access to this information.”

When asked what she thinks of these assertions, Merkwae says: “That’s bullshit. I think they know it is absolutely not how it is going to play out.”

Records with a side of punishment

Under the new law, records requesters can ask for an exemption to redaction fees if they provide “written certification” that they won’t use the records for “financial gain.” But if the police think you’ve done this under false pretenses, they can subject you to a forfeiture of $10,000, per violation, if a county District Attorney goes along with it.

This punitive threat is highly unusual in open-records law. People seeking public records accept a number of risks—denials, hefty copying fees, redactions, bureaucratic runarounds. But they almost never take on the risk of the government punishing them for making the request for the wrong reasons. Again, the reasons generally aren’t supposed to matter in the first place.

“I’m not aware of any other provision like this,” says Adam Marshall, a senior staff attorney with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP), considering the punitive fine provision in a national context.

“It’s very unusual. There’s nothing like it in Wisconsin’s law,” says Tom Kamenick of the Wisconsin Transparency Project, a Port Washington-based law firm that focuses on open-government issues. Wisconsin law already limited the rights of incarcerated people to request public records. But even then, Kamenick points out, “there’s no penalty provisions if you lie and say, ‘I’m not incarcerated’ or something when you’re making a request.”

Wisconsin’s greater body of open records law already provides for punitive measures, but going the opposite direction. An official who “arbitrarily or capriciously denies or delays response to a request or charges excessive fees” can be fined. Up to $1,000. (A court can also award punitive damages to a plaintiff in an open-records lawsuit.)

That’s right: Act 253 has created an open-records landscape where members of the public face 10 times the punishment the government faces for running afoul of the law.

And members of the public don’t even have the hope of being fined less than the maximum, in this case. “Notice that it doesn’t even say a forfeiture of up to $10,000, like almost all criminal and civil provisions with penalties say,” Kamenick says. “It just says $10,000.”

If you get fined under Act 253, you get fined for the whole $10K, period. The new law also draws no distinction between requesters who knowingly, intentionally provide a false certification and those who do it by accident. This makes it exceptionally harsh and rigid, even compared to other state laws designed to dole out punishment.

With or without Act 253, various processing charges can add up and create a real barrier to open-records access. It’s already an intimidating thing for most people to navigate. But in a worst-case scenario, a requester who doesn’t want to pay up can walk away empty-handed without fear of being punished. The new law raises the stakes, making a request for police video or audio downright frightening.

“It’s designed to really scare people off and discourage them from even making a record request,” Kamenick says.

In Dane County, it would ultimately be up to District Attorney Ismael Ozanne whether or not to pursue the $10,000 fine for requesters accused of violating Act 253’s “financial gain” provision. Ozanne did not respond to questions about whether he would enforce such a provision.

What does it all mean?

No one actually understands how Act 253 should work in practice, nor could they. The agencies already using it, or thinking about using it, are relying on advice from their attorneys. UWPD spokesperson Lovicott says his department “has worked with our internal experts, along with experts with the UW-Madison Office of Legal Affairs, to determine how it impacts related records requests that our department receives.” MPD has consulted the Madison City Attorney’s office, says Assistant City Attorney’s Adriana Peguero, the office’s open-records specialist. However, both Peguero and Lovicott say they haven’t seen any guidance from the Wisconsin Department of Justice on how to interpret the law.

Additionally, some of the pivotal language in Act 253 is essentially undefined in this particular legal context. Several other seasoned open-records experts (some attorneys, some not) spoke with Tone Madison for this story, and each of them expressed various degrees of confusion about what this thing actually means.

“This law was not well-written,” Kamenick says. “It was not well-thought-out.”

It’s the state Attorney General’s job to determine the state’s official interpretation of a law, at least until the courts weigh in. Wisconsin AG Josh Kaul has not yet offered his reading of Act 253, nor has the state DOJ’s Office of Open Government (OOG).

The OOG provides extensive guidance that government officials all over Wisconsin can use to make sure they’re complying with open-records and open-meetings laws. It publishes the Wisconsin Public Records Law Compliance Guide, a 99-page manual that attempts to translate all the relevant statutes and case law into something like practical advice. The latest edition of the Compliance Guide came out in May 2024, but doesn’t mention Act 253 at all. It states that “An authority may not charge a requester for the costs of deleting, or ‘redacting,’ non-disclosable information included in responsive records.” This is still true for everyone except law enforcement. But the state DOJ has yet to give Wisconsin police and corrections agencies any guidance about how to use their new authority to charge redaction fees. (OOG did not respond to a request for comment for this story.)

State legislators, among other officials, can ask the state AG to issue formal opinions on the meaning of state statutes. I asked the office of my Assembly member, District 76 Rep. Francesca Hong (one of three Assembly members who voted against the bill), if they’d be willing to reach out to the DOJ for an opinion on Act 253. Hong’s office contacted the DOJ and the state’s Legislative Reference Bureau (LRB). As of this article’s publication, the DOJ has not responded, but LRB analyst Spencer Johnson did send back a memo, writing that the new law “does not explicitly mandate how DOJ or any other law enforcement agency is to implement its provisions.”

The memo also states: “We are unsure how DOJ interprets this act.”

As police around Wisconsin amass a relatively new form of public records, Kaul’s DOJ has shown little leadership on matters of government transparency. Kaul hasn’t officially weighed in on an open-records question since 2021, when he issued an advisory on the implications of Marsy’s Law, a constitutional amendment that purported to protect the rights of crime victims.

Kamenick, of the Wisconsin Transparency Project, says that Kaul’s DOJ has been lax about open-records guidance generally, even when it comes to informally responding to inquiries from ordinary Wisconsin residents. “Frankly, that’s also something that this Attorney General has been dropping the ball on, because that’s been taking a year-plus, typically, to get a response on a letter request like that. And frankly, responses have gotten less and less useful,” Kamenick says. “It’s a lot of boilerplate, mostly taken from the Compliance Guide.” Under Kaul, the DOJ has also itself fallen behind on handling open-records requests, as the Wisconsin Examiner‘s Henry Redman reported in March 2023.

There’s also no clear, agreed-upon way to define “financial gain” when it comes to a public records request in Wisconsin. This is the phrase that could cost requesters $10,000, but Act 253 does not clearly define it. Nor does anything in Wisconsin’s open-records laws—up to this point, the statute hasn’t made any distinctions based on how a given requester intends to use a record. “‘Financial gain,’ as used in Wis. Stat. § 19.35 (3) (h) 3. a., is not defined under the act nor elsewhere in Chapter 19,” LRB analyst Johnson wrote in the memo to Rep. Hong’s office. “However, note that Wis. Stat. § 19.35 (3) (h) 3. a. also provides that ‘an award of damages in a civil action’ does not constitute ‘financial gain.'”

The Wisconsin Supreme Court has repeatedly declined to limit records access based on whether or not a requester could make money from the records. It has even pushed back against an arcane inverse of Act 253’s provisions. In an 1887 ruling in Hanson v. Eichstaedt, the Wisconsin Supreme Court “rejected the old common-law rule that a person had to have a specific, personal interest in a public record to get access,” as Kamenick sums it up.

As the RCFP’s Adam Marshall puts it, this new law “really doesn’t define [‘financial gain’] affirmatively, in any way.” For now, it’s entirely up to individual police agencies and the attorneys representing their respective local governments to determine who is using public records for financial gain under Act 253, leaving the door open to a broad interpretation that could ensnare all manner of requesters working in the public interest.

Could it apply to a non-profit advocacy group that solicits donations? An academic researcher who eventually makes some income from a book that cites police video or audio? An individual activist who gathers mutual-aid contributions on Venmo? A freelance writer pursuing the notoriously lucrative career path of journalism? If someone makes money from a project that incorporates these records somehow, is there any way to prove that they specifically made money because of the inclusion of those records? And when a body-cam video makes it onto the internet via a requester who somehow exists outside the transactional current that ensnare us all, what’s to keep anyone else from using that footage for financial gain?

In reporting this story, I’ve come across precisely one semi-specific example of the kind of “financial gain” police are supposedly looking to discourage with the new law: People slapping body-camera footage on YouTube to make easy ad revenue.

The Badger State Sheriffs’ Association complained about this practice in written testimony in support of Act 253: “For example, one Wisconsin sheriff recently reported that they are being inundated with requests for squad/body camera video from YouTubers who make money by sharing law enforcement videos on their YouTube channel. In fact, the YouTubers submitted six requests over the course of one night!” (This written testimony doesn’t back up the anecdote with anything remotely specific, which is stupid because public records requests are themselves matters of public record.) Wausau police chief Matthew Barnes and Democratic District 71 Rep. Katrina Shankland also railed against the YouTubers while stumping for the bill. UWPD spokesperson Lovicott also mentioned the YouTube example in a recent conversation with me about Tone Madison‘s open-records request.

It’s important to note that public records are not private intellectual property. If a government record is appropriate to release publicly, then it belongs to everyone. A YouTuber making a quick buck from these materials is, well, just the cost of having a modicum of transparency in our society.

The Federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) does allow the government to charge more fees to “commercial use” requesters. But in contrast with Act 253’s sloppy application of “financial gain,” FOIA actually goes to the trouble of defining what “commercial” means in the context of the law. It also differentiates between commercial requesters and several other categories of requesters, including educational institutions, non-commercial scientific institutions, and members of the news media. This is important, because a free society with a free press must be able to distinguish between a given media outlet’s business model and its civic function.

“Even in the federal FOIA, there are certain references to commercial requesters or commercial use of records,” RCFP staff attorney Marshall says. “But courts have interpreted that to not include members of the news media, including for-profit news media, because the purpose of news media requesting and disseminating information is primarily to inform the public.”

Wisconsin’s open-records laws, pre- or post-Act 253, don’t explicitly set the news media aside as a special class of requester. That is in part because, pre-253, they didn’t set aside financial gain or any specific purpose for different treatment. Again, the state’s courts have historically defended the notion that a records requester’s motivation doesn’t matter. Kamenick points to the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 1965 ruling in State ex rel. Youmans v. Owens, which stated “That [the plaintiff’s] motivation in seeking inspection is to benefit his newspaper [the Waukesha Freeman] and permit it to publish the material gained therefrom is immaterial.” In 1969, Wisconsin Attorney General Robert Warren even issued a formal opinion that explicitly defended commercial uses of public records: “The right to inspect and copy public records is in general extended to those who are engaged in the business of searching public records and furnishing to customers the information which is to be gained therefrom.”

Both UWPD and the Madison City Attorney’s office currently interpret Act 253 such that it does not exempt news media requesters. In fact, UWPD spokesperson Lovicott claims that an earlier version of the bill exempted media outlets, “but legislators eventually removed that exemption. This action solidifies our interpretation that media organizations are not exempt.”

Trouble is, going back through the legislative history, I can’t find that earlier edition of the bill, nor an amendment that touches one way or another upon media requests. The bill’s main State Senate sponsors (James, Feyen, and Wanggaard) and their legislative staff did not reply to requests for comment about how they intended the bill to be applied to media outlets.

And whatever its authors intended, police agencies around the state have choices about how they apply Act 253—including whether to apply it at all.

“I think one thing that’s important to recognize with respect to this provision of the law as well, is that it is optional,” Marshall says. “It says a law enforcement agency may impose a fee. I would hope and expect that law enforcement entities getting requests from members of the news media would not…impose any fee because of the valuable role that the news media plays in informing the public.”

Tone Madison will continue to explore the implications of Act 253 in the weeks ahead. Our coverage will include a closer look at our experience requesting body-camera footage from UWPD and its application of the law. If you’re a community member or Wisconsin-based journalist with thoughts on the subject, please feel welcome to email me.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.