“Light Needs” and “Parallel Botany” use the film medium as a means to map plant consciousness

Jesse McLean’s feature documentary, Magdalena Bermudez’s experimental short, and three other botanical shorts screen in a Wisconsin Film Festival program on April 6.

Jesse McLean’s feature documentary, Magdalena Bermudez’s experimental short, and three other botanical shorts screen in a Wisconsin Film Festival program on April 6.

Film is an ideal medium for artists with a naturalist bent since it doubles as an archive: analog prints can make direct transfers of any desirable sight or sound. But it’s rare for films about the natural world to be about it in the most true and direct sense—meaning, there’s always a mediating person or concept in their presentation. A plant can’t explain how photosynthesis feels, because a plant doesn’t have language or consciousness. Usually, filmmakers would just diagram it or have a scientist explain it verbally, but there’s untapped potential in this unknowability of the plant’s perspective.

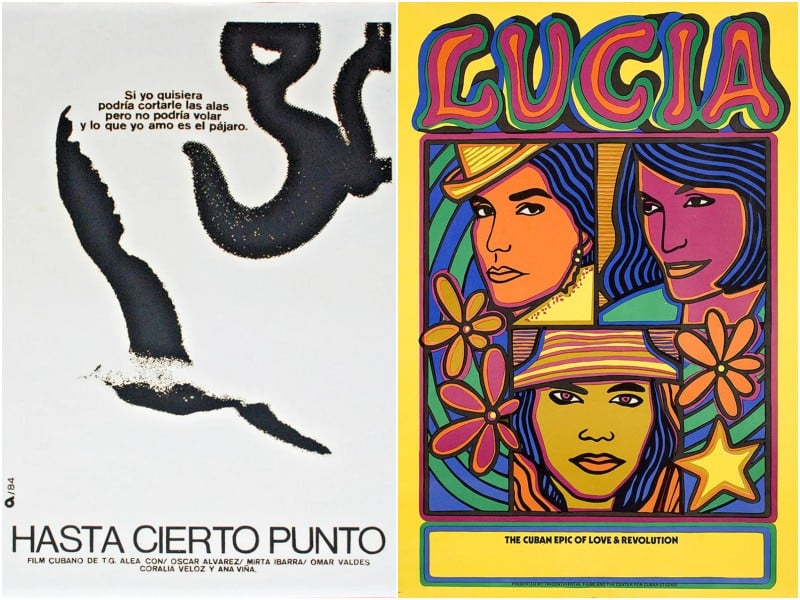

Given experimental filmmakers’ penchant for making difficult and unknowable work, it makes perfect sense that they’d be able to bridge our perceptual gap, exploring the lives of plants in unorthodox ways. And the 2024 Wisconsin Film Festival has gathered a locally sourced program, “Light Needs & Botanical Shorts,” which houses a feature-length documentary and four experimental shorts that each offer different possibilities. These films all premiere in Madison at the Chazen Museum of Art on Saturday, April 6, at 1:30 p.m. (As of publication, advance tickets are still available.)

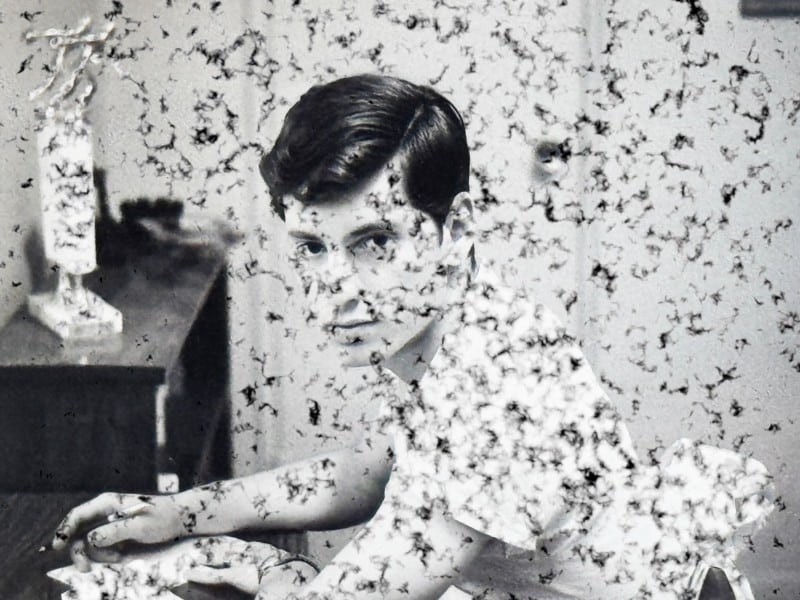

Light Needs (2023) is the feature debut for the Milwaukee-based Jesse McLean, who’s made short films and installation work since 2008. McLean’s interest in plants is focused here on the more domesticated sphere of house plants and their owners. For some interview subjects, their plants act as ties to distant people and places; for others, they’re neutral aesthetic objects. One couple argues off-camera about whether their plant is sick or not, providing a convenient metaphor for their relationship.

While these interview snippets provide some structure, the majority of the doc is spent simply observing the various subjects’ plants at home, with the camera obliquely eyeing them and sharing in their space just as their mindful or heedless owners might. McLean has said that the film “looks to shine a light on the responsibility for care towards other living beings,” and she does this by prioritizing the plants. Like its subjects, Light Needs feels like a piece of furniture, something meant to sit over there and be a reflective object. It’s a film that we share space with, and one that can gain a sort of projected sentience based on our biological connection to it.

The other naturalist short films that precede Light Needs in this film-fest program expand this scope a bit, from the loose narrative of Takahiro Suzuki’s electric moonlight & the language within the leaves (2023) to the Jodie Mack-esque abstraction of Kate Balsley’s Natura artis magistra (2022). But it’s Magdalena Bermudez’s Parallel Botany (2023) that most directly shares McLean’s interest in the incongruities of human-plant relationships.

In voiceover, Bermudez tells the story of an 1840 shipment of food between the East Indies and Holland that was thrown overboard due to crew reports that the fruit had begun reacting as if it were possessed, throbbing, hissing, and becoming discolored. Tracing an alternate future for this tragically cursed fruit, Bermudez imagines it arranged for still-life paintings instead, or dissected and diagrammed in the style of later naturalist drawings. But as she points out, cutting a plant in half does not reveal an interior, just creates two new exteriors. The desire to understand is only human, Parallel Botany seems to say, but the pursuit of knowledge down this non-human path is doomed and endless.

But that won’t stop the many artists and filmmakers from trying. As a unit, these films establish two poles of nature cinema: archival on one, and psychotronic on the other. While the dazzle of Balsley’s collage does the latter most obviously, it’s McLean and Bermudez’s considerations of the plants’ interiority (or lack thereof) that provide truly new territory for the human mind, considering the chemical baseness of plant experience that a human could hardly dream of. These filmmakers use the medium not just for artistic musing but for translation, in creating a voice for the voiceless or, in this case, consciousness for the unconscious.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.