You would think we would care

A violent arrest on Willy Street and our unconscionable blind spots.

A violent arrest on Willy Street and our unconscionable blind spots.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

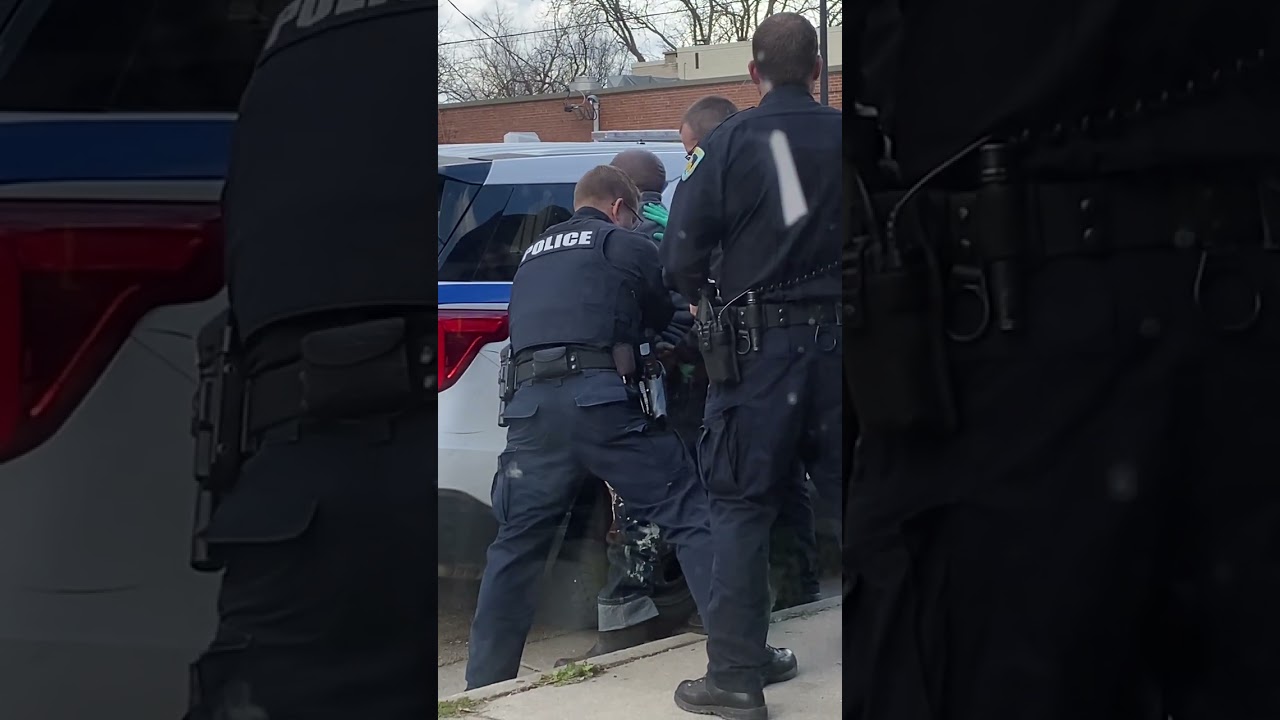

Are you disturbed about Madison police wrestling an elderly Black man to the ground in front of customers at a Willy Street diner? Because that happened, on November 21 at Willaby’s Cafe, 1351 Williamson St. It seems the only reason anyone is talking about it at all is that poet and writer Natasha Oladokun happened to be there that day. Oladokun took video of the arrest and drew attention to it on social media, and reached out to several City of Madison officials.

Oladokun spent several days trying to figure out whether the man had any access to care and services once he was released from jail. She followed up further, criticizing City officials for a lack of follow-through and critiquing the restaurant’s owner, Nathan Prince, over a Facebook post he made after the arrest. But if not for this one lone, persistent voice—the only other Black person in the place at the time—absolutely insisting that we pay attention to it, and that it should trouble our conscience as a city, would it have registered at all?

Madison365‘s Rodlyn-mae Banting (also a Tone Madison contributor) published a story about the incident last week, doing some much-needed reporting into the aftermath of the incident and the questions it raises. Why, for one, did the police show up, and not representatives from Madison’s Community Alternative Response Emergency Services (CARES) team, a relatively new program designed to handle behavioral health incidents? Banting spoke with Oladokun, Prince, and Madison’s Police Civilian Oversight Board chair Shadayra Kilroy-Flores.

In short, Willalby’s staff called the police on a customer, Willie Triplett, after a verbal altercation. Oladokun’s video picks up at the point that an officer is already there, trying to handcuff Triplett. Triplett shifts or takes a step—not fast, and not going anywhere. The officer, still holding onto Triplett’s hands behind his back, shoves Triplett to the floor and repeatedly says “quit resisting”—the way cops do when they’ve already begun manhandling people unnecessarily—as he wrestles Triplett onto his stomach and straddles him in the diner’s front doorway. After about a minute of this, a second officer shows up, gets down on the ground in the doorway, and, after some more “stop resisting” bullshit, holds Triplett down as the first officer finishes handcuffing him. They haul him outside, and shove him up against a squad car, and search his pockets.

And more cops keep showing up over the next few minutes. Oladokun, still recording, notes the presence of “five cops and four cop cars.” For this one guy who appears to have been in some sort of crisis and wasn’t physically violent. I’m sure the cops can give us a procedural explanation as to why this was all perfectly normal and rational, which just means that we’ve made all sorts of decisions along the way that made this outcome likely. And this happened at a time when Madison and Dane County both have alternate responses in place, for the express purpose of handling these situations safely without sending in armed cops.

What’s frustrating is that we don’t even know why CARES didn’t respond to this particular call. The service is still not available 24/7, but this incident happened during its 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. weekday operating hours. Based on Batning’s reporting, the staff who called 911 didn’t know to ask for it. That doesn’t fully explain it—this is an emergency service, and sometimes the callers will not be in a rational state of mind. As Dan Fitch noted in a 2022 story for Tone Madison about CARES and a similar program at UW-Madison, “Neither co-responder program has any option for a caller to explicitly request an unarmed response without police. Dispatchers make that decision based on their estimate of whether the situation is non-violent.” Later in the story, Fitch goes on to keep unpacking that blind spot:

Police are not trained mental health experts, and we should not expect them to be. But these pilots are currently limited in scope, and the power to decide who the co-responder team responds to and who the police respond to is somewhat hidden away, at the Dane County 911 dispatch and [UW-Madison Police Department] dispatch respectively. We need transparency in the future to ensure bias isn’t creeping in. Who, exactly, gets the privilege of this response style?

This still leaves us with the police as the default response to all sorts of situations. The default point of intake, such as it is, for people who need help. Try to get help in Madison, for someone, say, who is having a mental-health crisis, or someone who is stuck in a domestic-violence situation. Call around to the various private care agencies and non-profits that work on those issues. Try the City and County agencies, outside of law enforcement, that deal with health or social services on some level. Odds are very good that they’ll all ultimately tell you to call 911 and summon the police. You then really have to weigh that decision. Will the cops show up and hurt somebody? Will their mere presence make things worse? Will they just end up wasting time and accomplishing nothing at all? I’ve had some experiences trying to get anyone but the cops to step into situations like this, and it’s left me with even less faith in the system than before.

Here is the passage that jumped out at me the most in Banting’s story:

Prince admits to not having known about the services that the CARES team offers prior to this situation.

“I didn’t know about the CARES program,” he said. “I honestly had thought after George Floyd and everything, that MPD had done de-escalation [training].”

Kilfoy-Flores pointed out that this lack of knowledge isn’t unusual for the average Madison business owner, let alone community members at large.

So much of Madison’s self-image as a city works like this: people fill in the blanks by, at best, assuming we’ve already made more progress than we actually have, and, at worst, substituting wishful thinking. It’s not one person’s failing, either. It implicates all of us, or at least those of us who don’t bear the full brunt of bad policy in our day-to-day lives.

In my 18 years living in Madison, I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had with thoughtful, engaged, well-meaning people that have hit this kind of dead end. We end up talking past each other because one or both of us had a completely unexamined preconception about how well our community handles a given issue. Transit, housing protections, funding for all sorts of community needs, you name it. This rarely comes down to dishonesty or wilful self-deception. More often, it just doesn’t occur to us—again, those of us insulated by one form or another of economic or social advantage—that Madison could be screwing up that bad on the issue at hand. The question then becomes: Why aren’t we more inquisitive about it? Why do we settle for a comforting lack of answers? The resulting complacency creates even more obstacles to addressing the drivers of racial inequality in Madison. How do we move people to act when we can barely get the discussion started?

This dynamic is especially entrenched when it comes to policing. It doesn’t help that MPD is so invested in touting itself as a somehow exceptionally enlightened, assiduously de-escalating, progressive police department. (Which is kind of like being an enlightened medieval barber—hand me the humane, data-driven, community-based leeches, will you please?) It doesn’t help that credulous local media commentators keep buying that line, year after year, no matter how many troubling incidents pile up. (OK, at this point we are in the realm of dishonesty and wilful self-deception, at least at the institutional level.) So, of course a more casual observer—someone who doesn’t have to worry much about the cops hassling them or people they care about, or someone with a busy life—will likely buy it, too.

The prevailing narrative, well, prevails. But incidents like this remind us that we don’t have an excuse to look away. Where is our follow-through? When will we learn that when we are too easily satisfied with too little action, we leave people at the mercy of violent systems?

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.