What will the future of cinema look like?

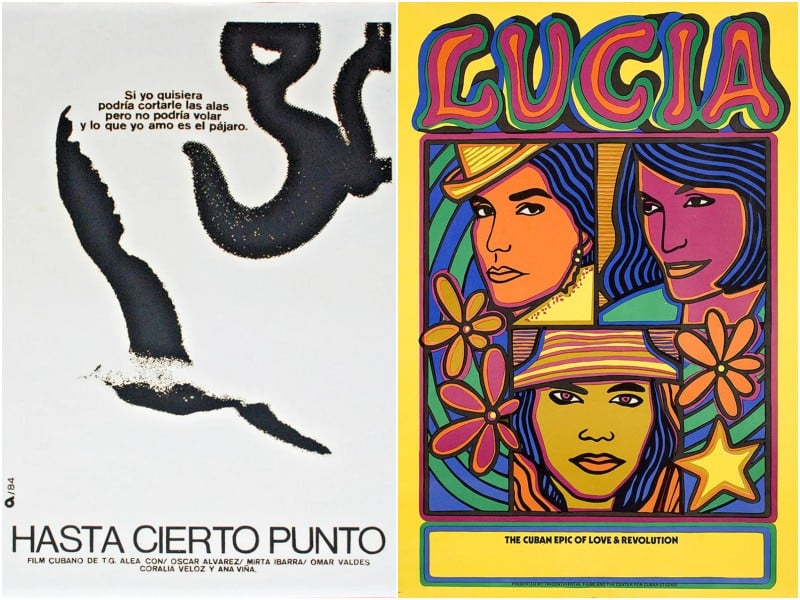

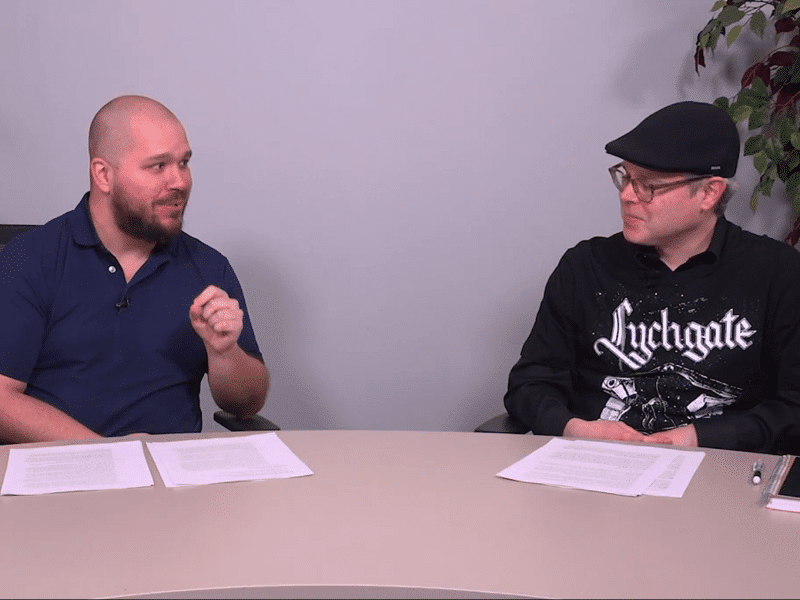

Film editor Grant Phipps and contributor Maxwell Courtright effusively ponder a question suggested by filmmaker Gina Telaroli.

Film editor Grant Phipps and contributor Maxwell Courtright effusively ponder a question suggested by filmmaker Gina Telaroli.

Film writing in Madison is too often tethered to immediately forthcoming events in the downtown area. If you blink, you’ll miss the one and only chance to see the films those pieces preview. As part of a specific effort to direct attention away from things that seem to have a measured arts-calendar expiration date, Tone Madison will be publishing more pieces that put its writers in open conversations, or “cinemails” as we’re tagging them, about assorted film topics over a period of time. That could mean dishing on a newer commercial release, expounding on a recent theatrical or streaming experience that they felt compelled to share, or something more broadly philosophical about the movies.

For this first edition of this conversational column, Tone Madison contributor Maxwell Courtright accepted the challenge of the latter, and plunged into a dialogue with film editor Grant Phipps. They pondered the future of cinema as it relates to this present, perplexing, ever-changing year.

Grant Phipps to Maxwell Courtright

subject: future of cinema

As this year’s Cannes was commencing in mid-May, I came across a tweet by NYC filmmaker Gina Telaroli concerning Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, which may be a monument or monstrosity. (It premiered May 16, and after facing distribution hurdles, Lionsgate will be releasing it in US theaters in the fall.) “I am insanely excited for MEGALOPOLIS but anything that costs 150 million isn’t the future of cinema.”

For further context on the film, Coppola had been striving to bring this epic film to fruition for more than four decades. He actually conceived of the evermore prescient fall-of-Rome/fall-of-the-United States narrative idea before the release of Apocalypse Now in 1979. After studio negotiation failures, Megalopolis became an entirely self-funded endeavor. Coppola sold his Sonoma County wineries and invested $120 million’s worth of earnings from that sale into the film’s budget. Exact reports of the budget remained somewhat unclear, but with marketing factored in, it likely exceeded $150 million.

With that knowledge, Telaroli’s comment led me to wonder: what will the future of cinema look like? Or will it just die out, as many have prognosticated throughout the 20th century and first quarter of this century?

Prior to the success of Inside Out 2 in June, the attendance and box-office numbers of the first five-plus months of the year were discouraging. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, in particular, saw incredibly diminishing returns, even after a sluggish opening during the extended Memorial Day weekend. Commentators and people concerned with the health of movies jumped on those reports, and what they may mean. But it will also be interesting to study complete year-end assessments when they become available in December and early January. Without a moviegoing event like last summer’s “Barbenheimer,” it’s hard to ascertain the media spin on the situation, and what various sources will declare, and how they will define the future of movies and movie theaters.

I’m hoping our conversation might also reveal some of the similarities and differences between the scenes in the cities where we’re currently living (as you, a one-time Madison resident, now reside in Chicago, and I live in Madison).

Maxwell Courtright to Grant Phipps

re: future of cinema

I agree with Telaroli’s take here, and would caution anyone against investing too heavily in what the “future” of cinema really is. I remember people saying similar things about the first Avatar when it came out in 2009, which arguably did more to hasten cinema’s death than bring in any sort of meaningful future.

I loved Challengers, and I’m glad that it had a long run at theaters (almost two months in Chicago as of this writing, with a physical media release the week of July 7). Whatever one thinks of it or finds it lacking, it worked wonderfully as big-screen entertainment, with not just beautiful but distinctive faces filling up the screen in real, embodied performances. This used to be what people went to the movies for, and some still do. But I think this is an interesting film for considering the “future” of cinema, since most of its good qualities (star charisma, snappy script, handsome cinematography) are so classical. This is, in most eras, a “good” movie, and its success among other, more bloated summer fare might be instructive: this is the type of film that many (i.e. franchise) films try to be, a sort of comedy/drama/romance/action hybrid, but just one that manages to stick the landing on each of its disparate forms of entertainment. I keep a running list of my favorites of the year and this is currently number one at least partly for this reason; it’s the most total movie I’ve seen this year.

I don’t have much of an issue accessing things I want to see in Chicago, though there are issues at any scale of distribution. I don’t like when Netflix-made films like Hit Man are barely available in theaters (and only at Alamo Drafthouse in Chicago, where I will not go despite their sporadically-good programming) or the fact that the new Tsai Ming-liang film Abiding Nowhere showed only for a single screening on a Monday morning. But these frustrations are pretty self-contained; and more and more, my favorite things in any given year are things I encounter (and may only exist on) the internet anyway.

My running second-favorite film of the year is a sports film of a different kind: Rob Taro’s new survey of Japanese skateboarding, Timescan 2. The video is a great showcase of skating, especially in its imaginative and most-viral section by the legendary Gou Miyagi. But what sets it apart is its creative editing and photography, intercutting skate footage with rapid celluloid cut-ups that feel borrowed from a Kurt Kren film. Experimental editing isn’t really a new thing in skate videos, and this one especially has the feel of Alien Workshop’s pioneering video-art-laden videos in the ’90s and 2000s.

Gosha Konyshev’s Skatefilm from this year similarly explodes the already-slippery form of the skate video by presenting an anthology of short films about skating, all created in different styles. While Russian and Japanese skate videos are maybe not the “state of the art” with film, I do think skate videos—specifically their formally untethered quality that positions them somewhere among sports dramas, cinema verite, and pornography—provide a blueprint for a possible future of film.

Something like The People’s Joker or the films of Jane Schoenbrun gaining such positive traction in the wake of Hollywood’s multiverse-craze supports this: Like the franchise films, these multimodal works also provide a sort of ur-artistic experience, in this case reflecting the complications of their makers instead of studio shareholders.

What this means for theater-going is unclear, as this type of work rarely makes it there in the first place (and only did selectively, after a bunch of legal back-and-forth in The People’s Joker‘s case). But I think there’s a will for more individual and challenging filmmaking in wide release; people just have to know about it. I think more attempts at massive IP integration will have to implode before the popular will for destination entertainment drives the industry in a major way, but we might already be part-way there if the studios can figure out a way to astroturf another “Barbenheimer” and make that summer-release strategy more of a trend.

You seem understandably pretty worried about the current theatrical scene, which I know has not served Madison well at all. It’s more of an economic question but, do you have any ideas for solutions? Alternative screening/venue setups, event integration, etc.

Grant Phipps to Maxwell Courtright

re: re: future of cinema

Am I as excited for Megalopolis as Telaroli? No, more like intrigued. But one of the reasons I picked her simple post-Cannes premiere reaction for a prompt is that it provides so many entries to discuss what films are being made right now, who’s making them, and what cinema means to each of us.

I would also add that we shouldn’t invest much of anything into a passion project made by one of the New Hollywood masters like Francis Ford Coppola, who turned 85 this past April, immortal as he (and his work) may seem. The process of funding Megalopolis was an ordeal in itself, and one that Lewis Peterson teased in his concluding sentences of the One From The Heart Reprise preview we published in February.

A Coppola model is patently unrealistic for, let’s say, every single aspiring and emerging filmmaker (lol), even those already blood-bound to the industry. Lately, I just feel like we aren’t actually hearing from filmmakers; we’re hearing from filmmakers as they’re filtered through the AI jargon of studios-corporations, who’ve tried to mold them in their desperation to make something, anything, that might attain cultural “permanence.” We saw this widely in its infant stages about a decade ago, when Disney and Universal were hand-plucking indie directors to helm their cinematic universes and franchises. Which might have originally been a noble thought, but capitalism can’t allow that, and I’d say most successes translated to the merely numerical. I don’t need to ask Lewis about his thoughts on Jurassic World, for instance, because I already know it’s one of his least favorite movies of all time.

In New York City, Film at Lincoln Center (FLC) has a recurring “New Directors/New Films” festival, which should be a model for every midsize city in North America. I realize that’s a bold assertion: FLC is in Manhattan, a kind of cinema epicenter and home to over 1.5 million people (and closely surrounded by other densely packed boroughs). But to me, that represents possibility. That’s hearing from filmmakers. Would it translate to Madison? Attendance is often driven by personal and local connection, and I wonder what sustained interest in a series like that would look like.

I will say that, last year, UW Cinematheque came pretty damn close to achieving a relative, scaled model with its fall premiere series on Thursdays (August 31 through November 16); and I’d be curious to see the attendance for those versus other series, or donations in response to that series versus others. The problem is that those screenings that Mike King programmed (and wrote little blurbs for) are always on the same day of the week. There’s only one show time for each film. Cinematheque can’t operate like a multiplex, so if you’re typically unavailable then, you’ll miss the vast majority. (And that’s not even accounting for parking downtown, a veritable shitshow at the moment.)

What I’m ultimately attempting to communicate is that I believe the future of cinema to be not-quite microbudget, but nearing mid-budget, and definitely more localized than in the prior century and prior decades this century. We’ll have simultaneously less of a consensus in establishing top-10 lists (truly a good thing after the homogeneity of 2023, my god), and more of a necessity for word-of-mouth promotion. And I know the latter isn’t a foreign concept in the awareness and breakout success of those mid-budget sorts of productions, if we consider certain horror and comedy flicks released between the late 1990s and late 2000s. This is a different era, though. Still true is that cinema’s survival requires that sort of attention, not just blindly following the path that a studio has laid out where the mood template and the narrative arc are known before even stepping through the front doors of the theater.

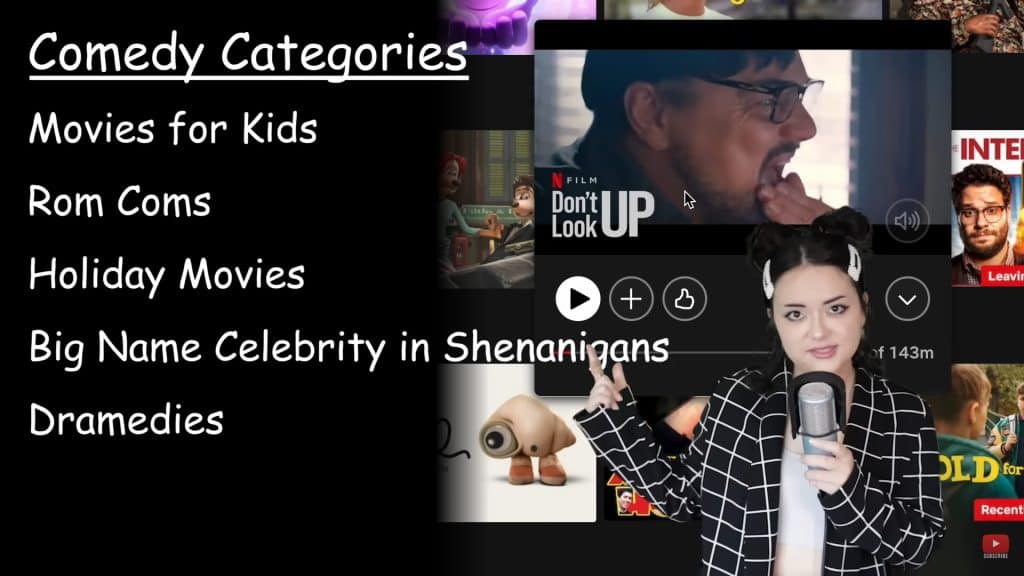

That kind of thinking in terms of movie-branding was perhaps inevitable, but it’s done damage to the experience long-term. Even younger audiences recognize this, like multihyphenate YouTuber Gabi Belle, whose primary output isn’t even cinema-related, but recently commented on the sad state of feature comedies. That part of movie culture doesn’t really exist right now. Writer and filmmaker Patrick H. Willems documented all this in a compelling and well-researched video episode in October 2023 about the intersection of suspects in the “death” of cinema. It no longer seems like speculation after all the erroneous prognostication throughout the 20th century; we can’t be surprised to learn that greed and risk-aversion are the two primary contributors to quality decline.

The kind of spectacle that movie studios are trying to achieve right now also can’t be compared to the medium of video games, which are as mainstream as they’ve ever been, partly because they have emulated big-screen entertainment. But it’s also because of live-streaming platforms that now allow so many people to watch a winsome personality play something for the first time, reducing the barrier to entry. Not only can I play a game, but I can watch others play it, too, compare strategies, and consider the game’s constructs (with challenge runs and custom-made modifiers) in a way that I wouldn’t if I were just picking up a controller to finish something myself.

Further, games are simply better at conveying spectacle and establishing a visceral link to the player/viewer and generating a sense of reward from that spectacle. Furiosa, for all its incredible stuntwork that’s on the level of the lauded Fury Road, can’t replicate that. I’m specifically thinking of Elden Ring and its recently released expansion, Shadow Of The Erdtree. Not only is the art direction in that game un-fucking-touchable, but the voice acting is nearly unanimously better than anything you’ll probably hear by live actors in a comparable movie.

Forgive my tangential fawning here, but I don’t think that movies striving for classic spectacle can continue to be a winning formula in the 2020s and 2030s, if we want to project that far. Games, even if they aren’t of that kind of caliber, are, in their present and future state, capable of doing spectacle better. That’s why I think cinema’s future has to be in the hands of smaller artists, working people who may/may not be directly supporting one another, bringing ingenuity to the fold in a way that the microbudget scenes of the 2010s did. (I owe a lot to Brandon Colvin and the Micro-Wave Cinema Series for that, surely.) These hypothetical but also very real people—’cause I know they’re out there—are more diverse and creatively envigored; they haven’t yet been conditioned by the industry to adopt antiquated methods and yield to algorithms or whatever metric corporate lords are using these days to feign relatability. Even if a major studio offers 10 of them a $15-million budget at best, the chances of their vision becoming realized with sincere innovation and newfound perspective is considerably higher than if studios put all their eggs into a $150-million basket.

I don’t know if these are solutions so much as meditations and wishes. It’s understandable to see an uptick in genre fare and action cinema in any cinema spot/venue around town, any town, but the expectation set by those films can be a turn-off for me, where it’s appealing for the average person. (Sorry to be contrarian, but I tend to rail against expectations set by fare that self-applies genre for built-in audiences.) We need to have more people—women, younger and gender non-conforming people—involved in programming movies in Madison, generally. And more people programming movies in places that are equipped for professional projection, not just relying on hooking up an HDMI cable to a projector and a laptop playing a 1080p (or worse) .mp4 file in VLC Player.

I’ve seen some cool and unusual spaces hosting movies in the past couple years, but most of the equipment boils down to that. We need to persuade all the wealthiest arts patrons around here that it’s not just about a cavalcade of outdoor music festivals during the summer months. Cinema needs to be tethered to the growing downtown community, even if films in question don’t necessarily hail from this community. The international can be in conversation with the local, and that scope makes things most interesting.

But all said here, thanks so much for the thorough response, Max. You’ve given me some idea of what’s going on in another Midwestern city, while bringing in your knowledge of Madison from your time here. With how often you frequent Chicago theaters, how much attention do you see put on this sort of local connection to Chicago filmmakers? If it’s persistent, it’s probably less forced and segmented than here due to the sheer population and makeup of Chicago compared to Madison. But I’m sure there are other differences, too, especially in terms of who is doing the programming.

With regard to your to-be-topped Challengers, I saw it with an engaged audience during its opening weekend, and I think I told you in person that I had some issues with it (what the hell was with that windstorm scene? so poorly executed), but noted some of its incredible, intimate sequences and duo of competing male co-leads. It does feel like a very complete movie in your framing, because it ticks many boxes, or parts of the court in this metaphor; but I’m wondering if its resonance is a result of the promise of ping-ponging sexual tension between the three characters/actors. And it just so happens that director Luca Guadagnino and writer Justin Kuritzkes generally harness that effectively to convey both poignant drama and hilarious passive-aggression on and off the court. I also thought about the “three tickets for Challengers, please” meme on socials, and the role in that inevitable marketing in simply getting people to show up, a kind of microcosm of last year’s “Barbenheimer.” Will that really be essential for the mainstream success of cinema in the future? For another conversation, maybe, but I think it can be an essential component in who goes to see certain films (versus who simply notices them); it’s the 21st century version of “word of mouth.”

Maxwell Courtright to Grant Phipps

re: re: re: future of cinema

I do think a more atomized filmgoing public (which, outside of the critical world, is already well underway with the feudal system of streaming services that fewer and fewer people wholly subscribe to) will help to diversify criticism and things like year-end lists. One possible downside of that, though, is that a dearth of perspectives on each new film coming out does limit the critical depth that might be explored. Like in scientific research, there’s value to a plurality of writing on any one topic even (or especially) if that writing reifies similar readings.

But one thing I bristle at with under-covered films is that what is written is not always helpful to a reader that hasn’t seen the film, or one who has and wants some more context. If, for instance, two people total have covered a film, one totally loving it and one totally hating it, that’s not exactly a helpful body of criticism to those trying to get the lay of the land. Should that matter to a viewer? Not necessarily, and maybe I’m overestimating how critical literature would guide viewers.

I Saw The TV Glow is another instructive example of this: a film that’s produced a lot of interesting criticism specifically by underrepresented voices, people who may or may not have had an opportunity to see the film if not for its wider release. If the critical literature on this film was only from a handful of trades employing established critics who saw it at a festival, you might not even know the film is (explicitly, textually!) about trans people. The film, then, does or does not find its audience, and is doomed to be “rediscovered” perennially along with everything else not in the top 10% of box office earners.

“Not only can I play a game, but I can watch others play it, too, compare strategies, and consider the game’s constructs (with challenge runs and custom-made modifiers) in a way that I wouldn’t if I were just picking up a controller to finish something myself.”

This opens an interesting avenue for cinema too, where there’s an extra layer inviting the individual in, potentially holding a hand if they need it but ultimately serving more like an in-depth experiential trailer of the thing. I don’t know that the same could be easily done with cinema, but one imagines a Mystery Science Theater 3K-type movement of creators doing the same thing on Twitch. This would obviously be a compromised way to view a film for the first time, to say nothing of the potential copyright issues, but it would likely be a step-up from the current social media trend of encountering a film mostly through isolated clips, screenshots, and related memes. But yes, certainly microcinemas are the way. Recently, the 30-something capacity Sweet Void Cinema in Chicago has hosted a series of experimental screenings programmed by Josh Minsoo-Kim, including an eight-screening run of dozens of Stan Brakhage films, all of which sold out quickly. Brakhage is certainly as “name” an experimental filmmaker as they come and it remains to be seen if this is repeatable for other films and filmmakers. But with this model, there’s a pretty clear ceiling on the money that can be made, and the smaller non-profit loop more closely mirrors how DIY record labels are structured (undergirded with lots of unpaid labor, of course).

Grant Phipps to Maxwell Courtright

re: re: re: re: future of cinema

Some very trenchant and intriguing thoughts here, Max. I particularly like your take on the depth of critical exploration. I think I’d be willing to trade bad movies for less people writing about them, though. I realize that’s reductive as hell, but if there’s a more diverse group of movies circulating, perhaps that means critics and journalists themselves will be as well. Obviously, they don’t exactly correlate, but art-makers and their audiences are interrelated.

Film criticism isn’t a science, though I know you don’t mean it that way in your analogy. Maybe the not-even-underlying concern in your words is: are we doing enough to recruit new writers and voices in the modern-cinema landscape? How do we get more people in the habit of writing about film beyond what passes for a Letterboxd review these days? I covered this in my sort-of review of Evil Does Not Exist in May, so I’ll not dwell on that further.

“The dearth of perspectives” is probably more suited to a conversation about the state of journalism, but it seems reasonable to say that if you care about the quality of movies, you should care about the quality (and depth) of writing. I’m less concerned with the barometer of opinion. They may not build statues of critics, but I don’t think there are many living professional critics who have that thirst for recognition. We should encourage engaged people to share, regardless of their opinion on a particular movie, because views might actually crystallize and evolve through their own writing process.

These days I’m fed a lot of video essays about the state of film on YouTube based on my watch history. In the time since we started this thread, Tom van der Linden of Like Stories Of Old published a 40-minute piece about the death of cinematic curiosity. Without going on too much of a tangent here, van der Linden posits that, all of us, arguably, in some capacity, are reaching for the comforts of films that are clearest in their premises, and looking for relatability in characters above all (also part of the aforementioned, because it translates to the easily understood and agreed with).

Van der Linden references a couple broader essays by critics Caitlin Quinlan and Jeremy D. Larson, and extrapolates to consider the problem of overstimulation. And I don’t know how we solve that other than when we reach points of mental and physical fatigue and have to engage with something simpler or, even perhaps, non-media. So I guess it’s especially strange to me to regard challenging, overstimulating-by-design (and not overtly relatable) films like Megalopolis being made by some of the most renowned living filmmakers. We’re in the post-post-irony era, maybe evident by the existence and popularity of films like Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), which perhaps temporarily plugged a gap that was left by bigger-budget spectacles post-2019. But works like this can’t be sustained or produced routinely with any sort of quality control, and so the future of cinema has to be less aspirationally epic in that sense. And, if the most recent reports are true, maybe the future of cinema in theatrical exhibition is also wrapped up in these fast-paced, family-friendly animation franchises. While I haven’t seen Inside Out 2 and Despicable Me 4, I kinda wonder what about them is resonating with audiences. Or is it just that easily agreed-upon thing I referenced with van der Linden?

Games, at least as they currently exist, require a different kind of engagement than watching movies. I mean, yeah, that’s not controversial at all. But I find the medium both more active and passive at the same time. Active in that they require near-constant input and strategy, but passive in that their linearity can be disrupted, even in any so-called linear game. Players can disengage from subconscious thought or simply park the character/avatar in a corner of a map while taking an advised 10-minute break every hour (but no one does that, lol). As I said, I feel like if people are seeking action spectacle, it’s just a little easier to get that fix from games.

Watch parties have existed for a while, and the whole MST3K-like scenario-becoming-phenomenon you envision isn’t out of the question for film. But you’re also right to say it’d be distracted viewing, because the people who’d be in those chats would be looking more for contextual validation in reaction to some moment in the movie rather than just letting things unfold and processing them throughout the course of 90 to 130 minutes or whatever. Kind of reminds me of the current problematic trends on Letterboxd, where one-line memes are the norm, and the easiest takes to engage with have the most “likes.” Perhaps I’ve found myself juggling a multithreaded connection to van der Linden’s commentary, lol.

In the end, I hope we’ve thought about some of the industry’s trends and contradictions, and envisioned not only what we might like to see in the world but also a realistic idea of audience (and critical) engagement. I feel like film nerds or cinephiles seemingly exist in more cloistered or closed-off echo chambers compared to music nerds or audiophiles, and I hope putting these elongated texts out there in public, on a publication that isn’t exclusively or even really remotely devoted to film, can help others engage in dialogue with their own communities. Whether they watch movies sort of casually or seek out some of the more adventurous fare around our cities (Madison, Chicago) and, yes, on streaming platforms, they should know their interest is integral to shaping the future of the medium and its form.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.