The voyeurism of “Peeping Tom” still offers a transgressive take on trauma

Michael Powell’s quintessential 1960 psychological thriller screens at UW Cinematheque on January 26.

Michael Powell’s quintessential 1960 psychological thriller screens at UW Cinematheque on January 26.

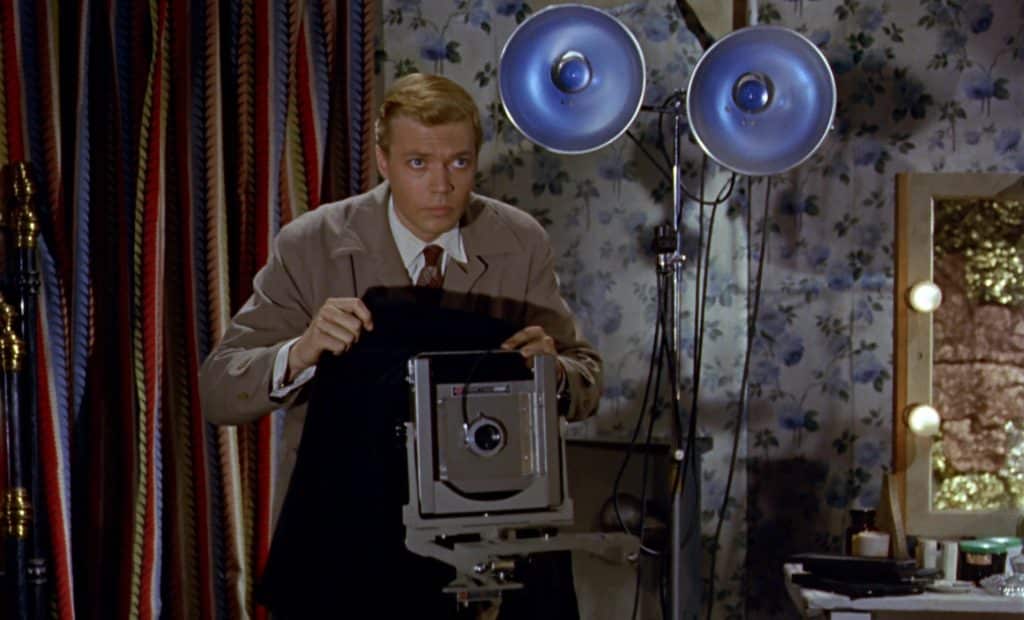

In 1960, Michael Powell directed the proto-slasher Peeping Tom, without his decades-long partner and collaborator, Emeric Pressburger. Predating Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho by only a handful of months, the film follows Mark Lewis (Karlheinz Boehm), a solitary man and member of a film crew, who photographs scantily clad women in his spare time, and secretly films and studies his killings of multiple London women. It’s a transgressive work that holds haunting questions more than 60 years later.

The film, screening in a 4K DCP restoration at UW Cinematheque on Friday, January 26, at 7 p.m., opens with an extreme close-up of a blue eye. It then cuts to a highly stylized version of a London street, which is reminiscent of the matte paintings in other Powell and Pressburger collaborations, like Black Narcissus (1947). With his eyes and camera lens, Powell immediately places audiences in the first-person perspective of our killer, as we watch Mark approach a sex worker and follow her inside. Mark captures her fear, kills her, and the film quickly cuts to him watching the film he has created in his own private theater inside his apartment. Powell has implicated us as accomplices in this act of violence.

Cinema is an art form made by perverts, sickos (laudatory), voyeurs, geniuses, monsters, visionaries; and, as the audience, we are complicit. We watch films with egregious torture, violence, and exploitation, and some of us are comforted by that. Films allow us to explore the deepest, darkest reaches of humanity, without actually having to become unsafe. In a 1999 review of Peeping Tom, Roger Ebert said that “the movies make us into voyeurs. We sit in the dark, watching other people’s lives. It is the bargain the cinema strikes with us, although most films are too well-behaved to mention it.”

Upon release, Peeping Tom ruined the well-established career of Michael Powell, but it has since been described as a masterpiece by advocates like Martin Scorsese, who’s recently explored similar themes of implicating the audience in his latest epic period drama, Killers Of The Flower Moon (2023).

Why did a film like Peeping Tom tarnish the reputation of Michael Powell, and why was Psycho met with praise since its release? Is it possible that Hitchcock heard of the negative press after a Peeping Tom screening and decided not to host his own film’s press screenings? Are Norman Bates’ mommy issues in Psycho more palatable to general audiences than Mark’s regarding his father in Peeping Tom?

While Psycho shares similar themes, is it possible that further linking voyeurism with filmmaking and moviegoing in Peeping Tom was too much for audiences to take? All these questions and more linger. Further, even, the meaning of the Old English term “peeping Tom,” with its origins in the legend of Lady Godiva, has transmogrified over centuries into lurker lingo of today.

If you respond to the shadowy devices of Peeping Tom, be sure to peep (in on) The Strangler (1970), which is screening at UW Cinematheque the following evening, January 27, at 7 p.m. Paul Vecchiali’s stylish and strange anti-giallo is a portrait of a young man who kills depressed women, the police officer who goes to extreme lengths to try and catch him, and a young woman who believes she will become his next victim. Where a traditional giallo would feature a sexy and thrilling tale about a leather-gloved killer, The Strangler emerges as a bleak character study about a man who believes himself to be doing good. Both it and Peeping Tom show two different yet similar tales of childhood trauma leading to murderous desire.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.