To trade in song

Bandcamp’s essential role and uncertain future.

Bandcamp’s essential role and uncertain future.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

I first started using Bandcamp in 2008 or 2009, as the local and touring artists I followed slowly began releasing music through the new platform. Even in those early days, Bandcamp had already achieved a clean, simple, user-friendly design and made it easy to buy digital music directly from a band or label. It’s hard to overstate how refreshing that was at the time. It’s also hard to overstate what’s at risk as the company changes hands for the second time.

Epic Games bought Bandcamp in 2022. In September 2023, the multibillion-dollar video-games company announced that it would cut half of Bandcamp’s staff as part of a company-wide slate of layoffs and sell Bandcamp to the music-licensing company Songtradr. In mid-October, Songtradr took the reins and extended job offers to half of Bandcamp’s staff, leaving the other half out of a job.

Those laid off included all eight members of the bargaining team representing the recently formed Bandcamp United union, 404 Media reported last week. The cuts also include half the staff of Bandcamp Daily, which launched in 2016 and quickly became the most curiosity-driven, hype-immune music journalism outlet on the internet.

All of this has prompted outrage and worried speculation from musicians, journalists, and fans. Pre-layoffs, Bandcamp had a staff of about 120 people. That’s not very big for a website that has millions of users and reports handling $193 million in sales in the past year. Will the 60 or so people remaining at Bandcamp be asked to do more with less? That’s no way for Songtradr to make good on its promise to maintain “business as usual” and integrate licensing opportunities into Bandcamp. Bandcamp Daily‘s remaining editorial team has stressed that the publication will keep going. Anyone who’s seen the do-more-with-less thing play out at a media outlet has got to feel for them right now. With some qualification, that is: Another 404 story, published Tuesday, revealed that Bandcamp editorial director J. Edward Keyes (who still has a job) made some nasty anti-union statements in May. Mostly, it just made me sad to see such ugly infighting behind such a great resource.

Bandcamp actually improved the conditions of doing business for independent musicians. It gave people tools without charging up-front. Its business model is set up to prioritize a fair payout to the artist, not payouts to the grifters and middlemen who’ve always made up a large portion of the music industry. It works for people who are hell-bent on having a full-time music career, it works for people who just want the satisfaction of putting their work out but don’t care about the business side, and it works for people at various points in between.

This is a rare approach. Usually, companies in the music business are more interested in selling artists on a chance to maybe, just possibly, leap after the brass ring. To get better at navigating conditions as they are. To become riper targets for exploitation. There is a whole ecosystem of Successories-pilled services aimed at feeding off musicians with big dreams, and it has created some of the saddest corners of the internet. For instance, the page where Songtradr CEO Paul Wiltshire showcases his own music.

Currently, musicians on Songtradr’s main service pay a monthly or annual subscription for distribution tools and a chance to get their work in front of people who need music for advertisements and other forms of Content. Music journalist Philip Sherburne put it best in an October 17 commentary for Pitchfork: “To Songtradr, which licenses mood music to advertisers and content creators, music is an add-on, an extra, a Pavlovian trigger to help brands sell more chalupas. To Bandcamp, music is unique, unrepeatable, the be-all and end-all—it’s everything.”

This is particularly frustrating when you recall the landscape Bandcamp entered upon its founding in 2007.

In the mid- and late-aughts, discovering independent music online often meant navigating the cheerful clutter of MySpace and its competitors. Anyone remember trying to listen to the music on a band’s MySpace page, but getting bombed with someone else’s music auto-playing way down in the comments? Even at the height of its Rupert Murdoch-backed dominance, MySpace was deeply unpleasant to use and just as chaotic behind the scenes (read tech journalist Julia Angwin’s book Stealing MySpace for an inside look at the shitshow). A lot of sites were trying different combinations of streaming, promotional tools, and proto-social-media features. The ones that enabled artists to sell music didn’t make it particularly smooth or convenient for the buyers.

Sometimes the search for a lesser-known act would take you across any number of platforms: CDBaby (no offense if you used it, but its online interface at that time was a real slice of hell designed to torment me, specifically), ReverbNation, PureVolume, and so on. I first heard Bon Iver’s music via a streaming site whose name I couldn’t even recall until I put the question to my Twitter mutuals: Virb.com (thanks to @akschaaf for figuring it out!). The vast ecosystem of music blogs that exploded during the decade was also a great way to hear new things. SoundCloud launched in fall 2008 and quickly attracted millions of users, but still took a few years to become a cultural force unto itself. Independent artists and labels could release music on iTunes in those days, but it could be daunting and opaque, not to mention the whole DRM thing. The subscription models of services like eMusic, for all their promise, could feel a bit convoluted. You could also Google a band name or album title and “.zip” and hope for the best.

Despite all of this competition and experimentation, some very important itches went largely unscratched until Bandcamp came along. And there’s still nothing that would quite replace it, which just ratchets up the present anxiety. By 2009 standards and 2023’s standards, it’s a snap for artists on Bandcamp to upload tracks, enter liner notes, attach album art, set prices, track sales, and get paid. The website’s format makes sense for a single or a full-length album, letting artists showcase their bodies of work in a way that feels both convenient and respectful to artistic intent. The revenue share Bandcamp takes from sales is transparent and reasonable. Even after the fees third-party payment processors take, the artist or label gets most of the money fans spend. Buyers can download their purchases in a range of different file formats, conveniently access their collections on desktop and mobile, browse album art and lyrics, and so on.

Bandcamp’s straightforward, user-friendly foundation makes up for the company’s sluggishness in developing other technical bells and whistles. For instance, Bandcamp didn’t introduce a playlist feature until February 2023, and it’s only available on the mobile app. Speaking of the mobile app, it gets the job done but doesn’t allow in-app purchases unless you’re buying a physical item. It leaves a lot else to be desired (please, when I click a Bandcamp link on my mobile browser, can it open in the app?). But these flaws just don’t seem that important, because Bandcamp does the basics so very well. It’s never had the vast development resources of Apple or Spotify. The upside to those limitations is that Bandcamp hasn’t followed the trend of algorithm-driven discovery. It has recommendations (often directly curated by artists) and best-seller charts, but encourages listeners to explore in a more active way.

This approach has made Bandcamp tremendously useful for listeners looking to follow specific musical niches, whether they’re sonic or geographic. I’ve covered Madison music on and off since 2006. For most of that time, I’ve relied heavily on Bandcamp to follow new releases, encounter local musicians I hadn’t heard of before, embed tracks in articles, and so on. It’s even helped me explore local music that happened well before my time, as artists began uploading older work and embraced Bandcamp as a platform for reissues. So much listening, so much trawling through releases with a “Madison” tag.

Of course, Bandcamp has always been a for-profit business and not an altruistic exercise. Despite all of his lofty pronouncements about not seeing music as a commodity, co-founder CEO Ethan Diamond set Bandcamp on its current treacherous path when he sold to Epic Games for an undisclosed price, no doubt securing a handsome payout for himself. Bandcamp does not have to release public financial information (it’s a privately held company, as are Epic Games and Songtradr), but Diamond has claimed that Bandcamp has been profitable since 2012. Still, the business model has coexisted with a communal spirit, an endless sprawl of musical abundance. Too bad that “leaving well enough alone” isn’t really a thing in an economic system that demands endless growth.

Concerns that Epic Games would upend Bandcamp’s ethos, or tamper disastrously with the user experience, never had time to play out in full. Well, except the obvious concern that a large company could turn around and dump its new acquisition. Epic Games re-sold Bandcamp as it laid off 16 percent of its overall workforce. In a September 28 press release announcing the sale, Songtradr pledged to “continue to operate Bandcamp as a marketplace and music community with an artist-first revenue share.” Songtradr’s actual behavior, though, fueled doubts about Bandcamp’s long-term future and even its ability to function smoothly during the transition. Wired reported on October 6 that Bandcamp staff had lost access “to many of the systems needed to do their jobs,” leaving them unable to carry out basic tasks like fixing bugs and responding to user support requests.

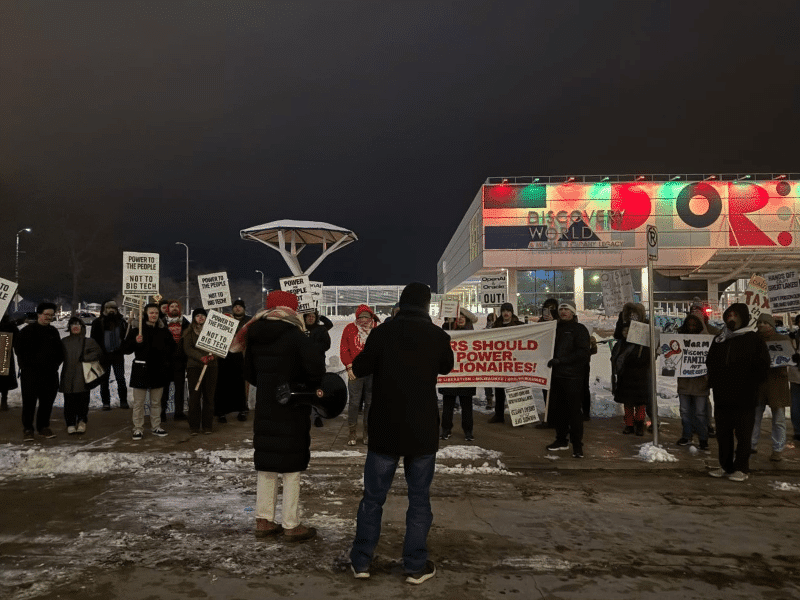

Meanwhile, Songtradr did not say whether or not it would recognize Bandcamp United, the union Bandcamp staffers officially formed with a successful May 2022 vote. (Fun fact: Bandcamp United is a part of the Office and Professional Employees International Union , or OPEIU, another local of which represents workers at Madison-based financial-services company TruStage.) The timing could not have been worse for the union: Like many unions in their first months after recognition, Bandcamp United had yet to finalize its first contract with Epic Games. Songtradr claimed that “Based on its current financials, Bandcamp requires some adjustments.” It didn’t explain how a long-profitable company got there.

Maybe Songtradr won’t mess too much with a good formula as long as people keep buying music on Bandcamp. That’s perhaps too much to hope for (see above re: leaving well enough alone). Adding a licensing angle to Bandcamp isn’t such a bad idea in and of itself, really. There’s money to be made in licensing, and I won’t judge artists for trying to get some of it when they’re getting screwed from every possible angle. The difficult part would be to align that with what Bandcamp is already doing—bringing simplicity and transparency to music-industry processes that are usually byzantine, opaque, and stacked against the artist. That, too, might be too much to hope for.

Most of the streaming and promo tools the internet has offered so far have been janky and tenuous. Bandcamp—a solid, sensible infrastructure that lets you listen to music and doesn’t torment you with ads or gimmicks or those fucking widgets—felt like it was built to last. This moment is so upsetting in part because users are confronting the possibility that Bandcamp could prove as mutable and disposable as anything else on the internet.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.