Three video artists tap into personal histories in the 150 Artists x 150 Years exhibition

Chele Isaac, Toby Kaufmann-Buhler, and Aaron Granat reveal the creative depths of their works, which are on display through February 28 at Central Library.

Photosynthesis. Hyperthymesia. Aphantasia.

Three nouns—one chemical process and two conditions—first appeared in the Merriam-Webster or Oxford English Dictionaries in the years 1898, 2006, and 2015, respectively. Divided by a century and then a decade, these year-defining words are thematically united under new video art and experimental films by Chele Isaac, Toby Kaufmann-Buhler, and Aaron Granat, which are available for viewing on the first and third floors at Madison Public Library (MPL) through the end of February.

They’re part of the expansive MPL exhibition, 150 Artists x 150 Years, under the curatorial purview of the Madison Bubbler. Reaching seven of the library system’s nine branches, the rubric of the project, which opened in mid-November, guided local and former Madison artists to create original work based on a randomly assigned word that entered the lexicon between the years of 1875 and 2024. This includes everything from “feel-good” a century and a half ago to the most recent “kintsugi” (pottery repair).

In more traditional gallery spaces that predominantly feature illustrations, paintings, sculpture, and photographs, digital video-art installations are fewer in number and demand a different, sustained level of engagement in their looped playback. But the act of experiencing them in tandem can also yield more intimate connections and meaningful responses in the Central Library’s atrium and open floor plan, as they force you to stand still for more than a few seconds to fully sink into the evolution of the artist’s perspective.

That is heavily emphasized in Isaac’s photo><synthesis (2025), which creatively riffs on the derivation of the term for the plant process of converting sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water into food. The five-minute-and-40-second video plays on repeat on an approximately 60″ TV mounted on the library’s first floor wall behind the “Too Good To Miss” reading tables. Isaac, who’s had abstract work exhibited at Madison Museum of Contemporary Art and collaborated with writer Quan Barry in 2023 for the Midwest Video Poetry Fest, focused intensely on the night-blooming cereus, a flowering cactus.

“It was the last plant I helped my mom re-pot, and it was a scraggly little mess that hardly seemed worth the effort. She said that one day it’d be beautiful. I had no idea what it was until it started blooming a year after she passed,” Isaac writes in an email to Tone Madison, a testament to her own process of discovery.

Watching the silent installation is like a slow-motion, kaleidoscopic version of Isaac Sherman’s a shifting pattern (2024). Where Sherman takes a mesmerizing strobe-light approach to floral photography, Issac opts for something more dreamlike or almost inkblot-like in photo><synthesis, the cereus’ pointed white petals softly shifting in the depth of field and shutter speeds in diffused fluorescent lighting. The subsequent frames are equally breathtaking, in the way Isaac superimposes mirroring images with petals folding into one another. The effect is of complete transformation, which makes the familiar sight of a flower and its parts—stamen, pistil, and ovules—appear like the abdomen of an insect, or cattails and tall grass in a marsh at night.

That is really what the installation evokes: nocturnal imagination. A 10-second sequence of a flower dropping into view in the top part of the frame in Issac’s video has the same momentous weight of a descending alien spacecraft in a big-budget feature film. And those are just a few striking analogies. In Issac’s reality of filming photo><synthesis, she paints a larger-than-life sensorial picture of experience: “The blooms open at night and die by morning. The fragrance is insane—jasmine. It’s visited by bats and large night moths… She’s enormous. Over sixty blooms in the course of five days.” Isaac reminds us of the boundless beauty and inspirations of the natural world.

150 Artists x 150 Years’ other two video works at Central Library offer a coincidentally intriguing pairing on human memory, and employ stereo sound (via headphones) to communicate that scope of human experience. Both Kaufmann-Buhler’s Eye Sees Time (2025) and Granat’s Aphantasia (2025) are displayed on an iPad and computer monitor, respectively, which are mounted on white pedestals along the west-facing wall on the library’s third floor (outside the Community Room 301 and 302) in the Diane Endres-Ballweg Gallery.

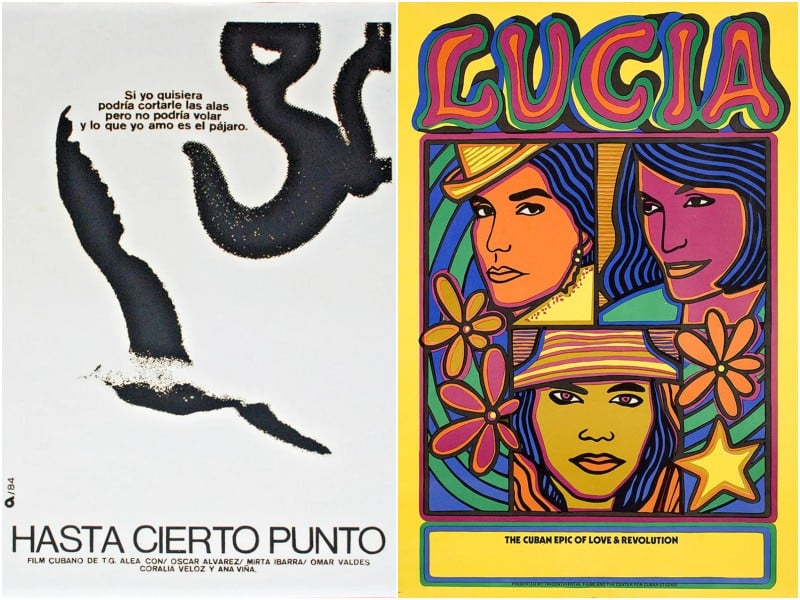

Kaufmann-Buhler, who lived in Madison for nearly 10 years and is now based in Lafayette, Indiana, translated the “hyperthymesia” term (recalling memories in vivid detail) into a four-minute video loop of blinking eyes, with six per horizontal row in a partly clipped four-by-four grid. To a degree, it evokes the pop art of Andy Warhol and the trippy tradition of extreme close-ups of the human eye throughout cinema history, but Kaufmann-Buhler navigates a more permeable and experimental landscape. The photo strip-like presentation will be familiar to anyone who can clearly conjure his exhibitions of the 2010s at the Watrous Gallery and Little Monroe Gallery as well as his subsequent visit to Madison in 2018.

While Kaufmann-Buhler has been away from the city’s art scene for some time, he writes to Tone Madison via email that he’s “kept up with the big art opportunities here” through invitation from MPL. The 150 Artists x 150 Years project, in particular, spoke to him because he was given a word that entered the English dictionary in 2006, the first year he lived in Madison. “[That] became as important to me in conceptualizing the work as the word choice,” he writes.

Thus, the basis for Eye Sees Time stems from works-in-progress during that time frame nearly 20 years ago. “Back then,” he explains, “I developed this method of video construction, ‘matrix frames,’ essentially inspired by the timeline-oriented methodology of digital video-editing.” Since the mid-2000s, though, Kaufmann-Buhler has steadily refined his craft, and so he treated Eye Sees Time as a kind of amalgamation and dialogue between versions of himself then and now. More recently, he’s been tinkering with real-time analog video synthesis. “I wanted to bring these methods together as a kind of collapse (or telescoping) of time, which I think connects to the involuntary memory condition,” Kaufmann-Buhler concludes.

On the surface, Eye Sees Time is the most simplistic of the three videos in the exhibition; but its depth of beauty is revealed in its subtle editing tricks and vertical, dissecting strips of color, and further elevated through the sonic software-processed oscillations of the singing saw, one of Kaufmann-Buhler’s preferred instruments for installation work.

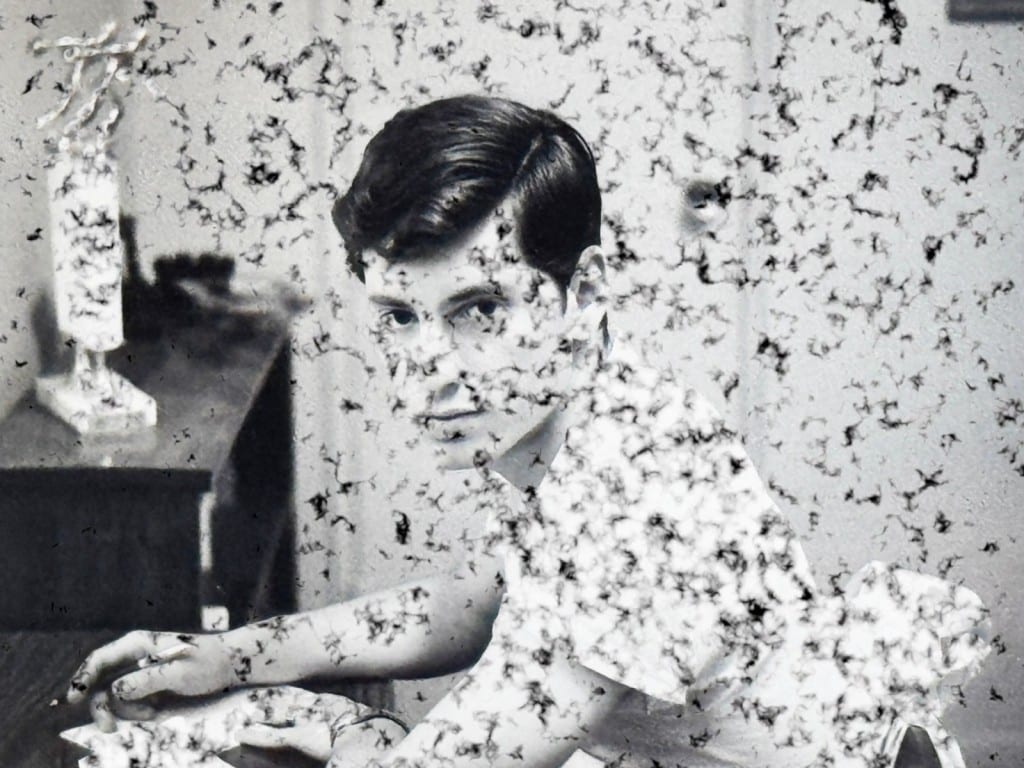

Just 15 feet away, Granat’s 10-minute Aphantasia is the most narrative- and audio-focused of the trio, and so it is more closely associated with the experimental short documentary format. Opposite Kaufmann-Buhler, Granat’s word prompt of the title refers to the absence of one’s ability to mentally visualize.

In his opening reception speech from this past December, Granat said that constructing a work from that word was quite serendipitous, because his father Michael discovered that he suffers from aphantasia. “I remember its entrance into the lexicon in 2015 really brought things into clarity for him, allowing him to situate himself relative to a greater spectrum of mental perceptual experience,” Granat said.

From the opening seconds of Aphantasia, Granat engages in a voiceover dialogue with Michael about the condition, over a static black-and-white photo dated May 1967. A few seconds later, the voice of Granat’s mother Kathy cuts in, reciting a chapter excerpt of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship Of The Ring. The verbalized words bring Michael back to a time in his graduate studies when he read the fantasy epic; and, through this stirring communication with Kathy, Michael realizes that others could mentally visualize a world for the terrain and voices for Hobbit characters in a way he could not. “The information’s there, but the graphics board is corrupted,” Michael tells his son in analogy, trying to best articulate the approximation of his awareness.

While Granat has often worked in a collaborative capacity, especially this decade, he undertakes this project as a solo endeavor, which reflects its association with immediate family. But Aphantasia is further testament to the range of Granat’s artistic vision, and reminds Madisonians that his potential has yet to be fully tapped. Whether tethering his skill to choreography, documentary, or live collagist mixing, he’s committed to expanding the possibilities of visual narrative.

Here, Granat intelligently and empathetically simulates his father’s “spiritual life,” as he says, by adding digital debris to this archival photo. The frayed black particles act as static, swarming the lightness of the image and obfuscating parts of his human form (and other recognizable objects in the frame like a trophy). In Granat’s aforementioned speech, he reinforced that by saying, “The imagery in the video is my attempt to aestheticize my own experience with mental images. I searched for unique ways to depict the fragility and instability of discernible imagery when viewed through the lens of cognitive analysis. The fluctuations, dissipation, and erosion of form into noise.”

As the conversation with his father and mother continues in Aphantasia, Granat inserts slides of other family photos—one of Michael as a baby from around 1950 and others from the 1980s—that are always slightly askew, positioned at a corner edge or at an extreme close-up, wavering in the approximation of blurry vision or painterly, impressionistic haze. The effect carries with it an ephemeral beauty, and Granat’s post-production choices complement Michael speaking of his amateur photography. To him, the hobby is less about permanence, filling an photo album’s pages, or frame-fitting than it is about the present state of being. “It’s a process of paying attention and creating things that are visually pleasing in the moment… I don’t have any sense of nostalgia,” Michael says in the film. In today’s climate, the expression is aspirational. Michael doesn’t feel any lack, nor does Granat’s work here.

Absorbing the scope of the MPL collaboration with the Bubbler in the 150 Artists x 150 Years exhibition can feel overwhelming, but the ideas explored in various mediums bridge time and space (and place) by dozens of current and former Madison-based multimedia artists. These three perceptive video works by Chele Isaac, Toby Kaufmann-Buhler, and Aaron Granat at the Central branch facilitate artistic connections between memory, language, and personal and/or family history in ways that should be celebrated and meaningfully engaged with at your opportunity—particularly as our reality seems to become increasingly shaped by virtual, fracturing distortions.

Editor’s note: The paragraph detailing Michael’s “The Fellowship Of The Ring” experience in “Aphantasia” has been corrected.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.