There will be no “climate haven”

Unpredictable rain and extreme heat will impact all of us.

Unpredictable rain and extreme heat will impact all of us.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

Richard Keller, a UW-Madison history professor and expert on the health impacts of climate change, says he’s been “joking with relatives in Texas as far back as 2003 that as their [climate change] problem was going to be getting worse, ours was going to be getting better.”

I’ve always been skeptical of the idea that Wisconsin will be a “climate haven,” but there is a kernel of truth in it. Other regions will be much more immediately and drastically impacted. The Great Lakes region and its coveted supply of freshwater will only become more and more attractive. As Keller points out, “if you look at the fastest-growing cities in the United States in the past two decades, the vast majority of them are in regions that are under direct threat from a changing climate.”

“So if you look, for example, at communities in Arizona, in California, in the Deep South, these are places where the climate problem is getting really acutely worse on a year by year basis,” Keller says. “To the extent that insurance companies are now indicating that a place like Phoenix may be uninhabitable within our lifetimes.”

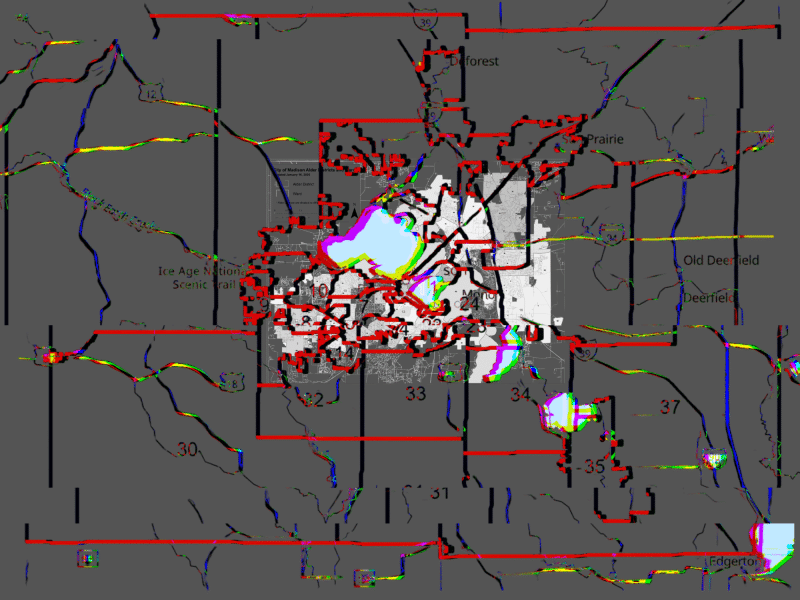

The narrative that Madison in particular is a “climate haven” has been gaining steam over the past few years. Media reports, including a 2021 Spectrum News segment, have reinforced the idea. Climate-savvy politicians including Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway have participated in, then touted those media reports, and on the cycle goes. Even climate ignoramuses on the right can’t resist the whiff of opportunism: One of our state’s top nitwits, Sen. Ron Johnson, latched on during a Senate budget hearing in April 2023. Also, Destination Madison, which receives millions in City funding, has an article using that narrative to promote tourism to Madison and Dane County, which feels pretty gross. All while U.S. migration studies find people are actually moving into more climate-vulnerable regions of the country, not to the so-called “havens.”

The narrative creates a false sense of security, a potential easy answer to this crisis, instead of doing the hard work of reducing carbon emissions. Seemingly out of spite, the summer of 2023 in Wisconsin brought a hot, dry spell that affected crops, and people across the state spent several weeks choking on wildfire smoke from Canada. While Wisconsin does a reasonably good job preventing and managing wildfires (due in large part to Indigenous forestry practices), smoke does not recognize borders, much like climate change itself.

By comparison, this past summer was milder, but it still highlighted the many problems Wisconsin will face. Wisconsin is certainly not on the same trajectory as our southern neighbors, but there are gaping holes in the “climate haven” narrative: wildfires, floods and droughts caused by unpredictable rainfall, and—probably the most overlooked and most dangerous—extreme heat.

Wisconsin, and Madison in particular, already has a housing shortage. Telling the rest of the country to come on over when it gets too hot at other latitudes will only exacerbate the problem (though it will make a lot of slumlords happy). Also, in my lived experience, a lot of Wisconsin apartments are built for winter, not summer, and certainly not the type of summers we’re already experiencing under climate change.

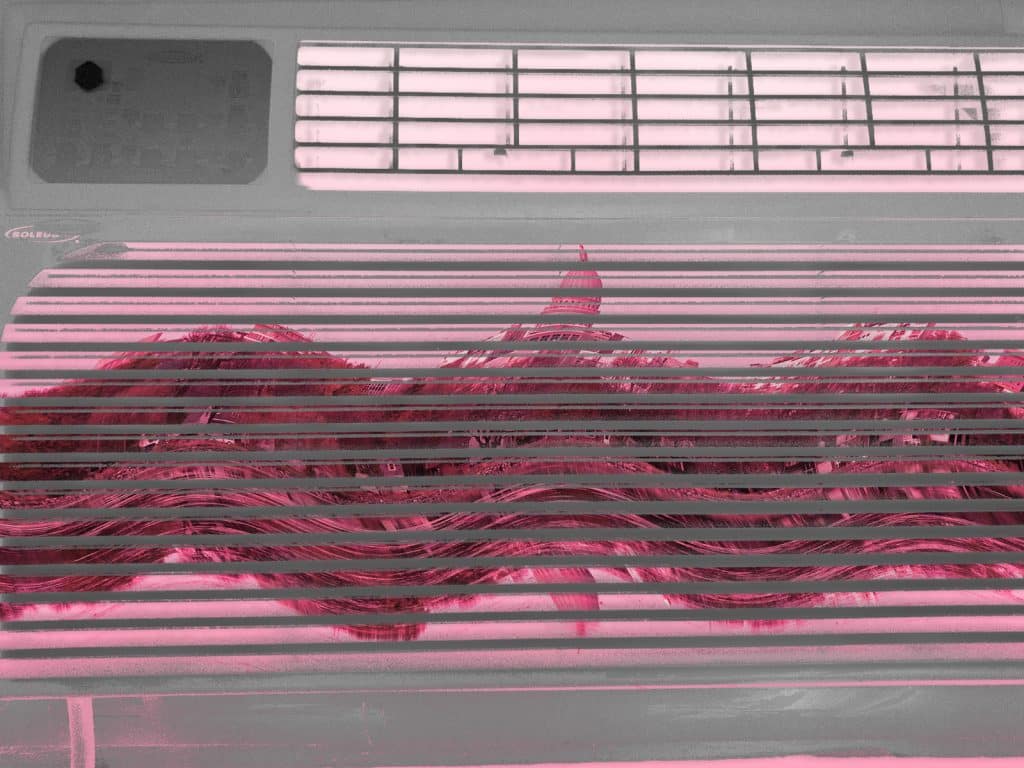

“As far back as 1995 it was pretty apparent that, actually colder climates tend to suffer worse from extreme summer heat than warmer climates,” Keller says. He points to the 1995 heat wave in Chicago—”which most of us think of as a cold city rather than a hot city”—that killed more than 750 people in three days. Keller’s 2015 book, Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave Of 2003, analyzes how Paris’ small, poorly-ventilated apartments with no air conditioning contributed to the deaths of over 1,000 people in two weeks.

Keller says we are starting to see that trend in Wisconsin as well, “where hotter summers are seeing rising hospital admissions in cities like Milwaukee with extreme heat waves.” And we may not even know the full impact of heat waves because heat deaths are undercounted.

Maybe a few decades ago when a lot of our aged, inexpensive housing was built, you could get through a Wisconsin summer opening the windows and maybe running an AC unit during the hottest part of the day. That is not the reality anymore, and many low-income households have to weigh the cost of running their AC units against the toll the heat has on their bodies. Back in 2022, amid heat waves that pushed temperatures into the 90s in May, major Madison landlord JSW Companies banned its tenants from installing window AC units.

People with central air can ignore these tradeoffs (if not the hefty power bills), or even have the audacity to judge others for running their units. My local utility sends out emails and flyers reminding residents to conserve energy by turning up thermostats to 78-, even 76-degrees. Meanwhile, up until last weekend, my thermostat hadn’t dipped below 78 since April. I’m cool and comfy at 80 with a fan and low humidity, but not by choice.

“There’s this, I think, false notion that air conditioning is more of a luxury than a necessity in the built environment in Wisconsin,” Keller says. “And I think every summer is proving, really, showing why [that notion is false].”

There’s also the issue of rain. Sure, Wisconsin doesn’t have to worry about sea level rise, but have you looked at our lakes lately? Lakes Mendota, Monona, and Wingra are full to the brim, and this is after the extreme drought last year. That’s because rising temperatures cause greater evaporation, so clouds get bigger and heavier. When they break and the rain comes, the clouds also move more slowly, so the clouds dump a lot more rain on a smaller area. Instead of nice, easy rains that refill the lakes and water the plants, we’ll get either flood or drought. While the city has laid out flood mitigation plans, particularly in response to the 2018 flood, at the end of the day, the isthmus is low-lying land surrounded by rising water. There is only so much that can be done.

Both flooding and drought, by the way, cause compaction in soil, which is where the soil is more densely packed with little air. Compaction makes it harder to plant and it makes it harder for plant roots to spread and take hold. Whichever way the rains go, it’ll impact our ability to grow food.

The “climate haven” boosters in Madison like to gloss over all of this, instead preferring to tout the fact that our winters are getting milder. “What we like to say here is that there’s no bad weather, there’s only bad clothing,” Rhodes-Conway told CBS News in a 2021 report. Sure, we’ll have milder winters, enough fresh water (we think), and a longer growing season. But that could also mean more mosquitos and less predictable growing seasons that affect crops. As Keller says, “it’s a mixed bag.” Because climate change is also incredibly unpredictable.

“The other issue too is that as we see our winters get warmer, we don’t know exactly what that’s going to mean,” Keller says. “That might actually mean that winters are far snowier, or it may actually lead to drier springs. It’s hard to say what the effects are going to be. So, with something as unpredictable as climate change, I don’t think we really want to think about a place as a one-size-fits all solution to the problem.”

The heart of the problem with presenting “climate havens” as a solution is that inequity is baked in. Large segments of the southern US population are barely getting by, and certainly do not have the means to pack up and move to another state (and that’s not even touching on the issues in the Global South). The people who can move will have the resources to displace poorer northerners. As Keller says, “It’s a solution that seems made for people who already have lots of solutions at their disposal.”

Lower-income people, and even middle-class people, have microscopic carbon footprints compared to those of the wealthy, (hell, Ron Johnson’s private jet—technically owned by his children, sure— has added more carbon to the atmosphere than I probably have in my entire life). But of course, those of us with the least resources will be pushed into the regions where the impacts are the worst and bear the brunt of the consequences and chaos. We could become a nation segregated along lines of latitude, where “climate havens” are cold comfort to most.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.