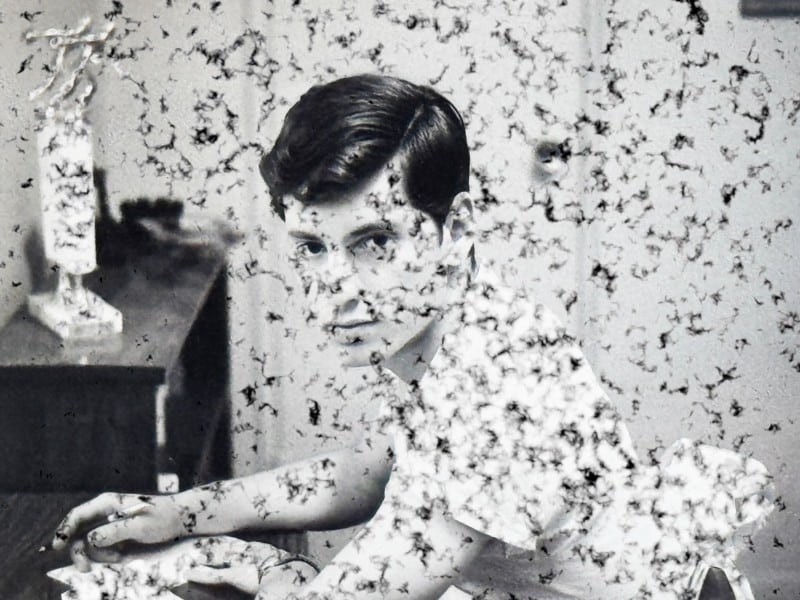

“The Battle Of Algiers” radically confronts the horrors of French imperialism

UW Cinematheque presents the innovative and still-urgently relevant 1966 film of political upheaval on March 14.

UW Cinematheque presents the innovative and still-urgently relevant 1966 film of political upheaval on March 14.

Where is the line between historical fiction and documentary? I remember wondering at the distinction and its implications upon emerging from a screening of The Battle Of Algiers, years ago when it played on UW campus. UW Cinematheque is once again presenting the film locally, and on 35mm, this Friday, March 14, at 7 p.m. in 4070 Vilas Hall.

The 1966 political drama, by Italian writer-director Gillo Pontecorvo, was like nothing I’d seen before: Clearly a narrative feature, but populated with crowd scenes so large and complex as to look and feel real, as well as casting choices that incorporated people who were actually involved in the events being depicted. These elements collectively brought a depth of emotional and physical honesty not often seen in movies of its era (or now), part of the homegrown Italian cinema tradition of neorealism.

This was all an intentional choice by Pontecorvo, who experimented with various techniques to make parts of the movie look and feel like a newsreel and documentary. Pontecorvo also cast non-professional Algerian actors for the majority of the roles, choosing them “more for their physical verisimilitude than their innate ability,” as film scholar Peter Matthews noted in a 2011 essay for The Criterion Collection. The only professional actor of stage and screen in the movie, in fact, is Jean Martin. He plays the commander of French paratroopers, Lieutenant-Colonel Mathieu, who’s called in to quell the resistance.

Filmed less than a decade after the real-life events, the movie follows some of the early pivotal moments and figures in the Algerian War for independence from French colonial rule, specifically between 1954 and 1957. And it pulls no punches from the jump, as it opens on the figure of a clearly torture-broken Algerian man in French military captivity, tearfully giving up the location of Ali La Pointe (Brahim Haggiag), one of the resistance leaders. Ali and his compatriots’ faces are grim but determined, trapped and about to be blown up by French paratroopers.

The Battle Of Algiers then flashes back several years, when La Pointe is first recruited by the revolutionary National Liberation Front (FLN) during a stint in prison. From there, the film introduces FLN leader El-hadi Jafar (played by actual Algerian revolutionary and politician Saadi Yacef, whose memoirs of the war served as some of the basis for the script), along with a handful of other key players, including three women who participate in the bombings of French civilian targets in retaliation for French police bombing civilian targets themselves.

Pontecorvo’s ultimate sympathies clearly lay with the Algerian people’s struggles for self-rule, but the film also never shies away from the harsh realities of the war. Lingering shots of regular people, including small children going about their days before being caught up in FLN bombing attacks, force the viewer to engage with the totality of the horrors that result from occupation and resistance.

But the majority of the film’s unflinching eye is turned on the French, both the heavy-handed tactics of police and military—including scenes of torture that were initially edited out of the movie for its initial release in America and the U.K.—and of French civilians turning on and beating Algerian children and adults they happened to catch in their midst.

“Should we remain in Algeria? If you answer ‘yes,’ then you must accept all the necessary consequences,” Lieutenant-Colonel Mathieu declares to a room full of French reporters late in the movie, as efforts ramp up to destroy the resistance. The scene then shifts directly to an extended depiction of the torture of suspected Algerian insurgents, showing the exact reality of those consequences that the French public seems willing to excuse.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, reaction to the movie in 1966 France was overwhelmingly negative. The Battle Of Algiers is considered to be the first film to truly confront the issue of French imperialism. The French government banned it from being screened in the country for one year, and no French distributor would touch it for several years thereafter. (An interesting parallel is playing out now, with the Oscar-winning No Other Land, a documentary about Israel’s destruction of Palestinian villages in the occupied West Bank and the resistance to it, and the refusal so far by U.S. distributors to pick it up.) Meanwhile, Algiers won international acclaim and quickly became a popular piece of inspiration for revolutionary groups like the Black Panthers, the Irish Republican Army, Palestine Liberation Organization, and others. The Pentagon even held a screening in 2003, ostensibly to help commanders and troops facing a similar insurgency in occupied Iraq better understand their circumstances.

It’s since been widely recognized as one of the great movies of the 20th century by a range of critics, political figures, writers, and regular moviegoers alike. And I do feel like The Battle Of Algiers holds up remarkably well, both as a piece of cinema and as an examination of oppression and resistance. Perhaps that’s a sad commentary on the state of world affairs some 60 years on.

As the saying goes, history may not repeat, but it often rhymes. We’re fortunate to still have access to such vital filmmaking that stands the test of time, and filmmakers who can hold up a mirror to our worst—and best—impulses as human beings.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.