Terror at the edge of the earth

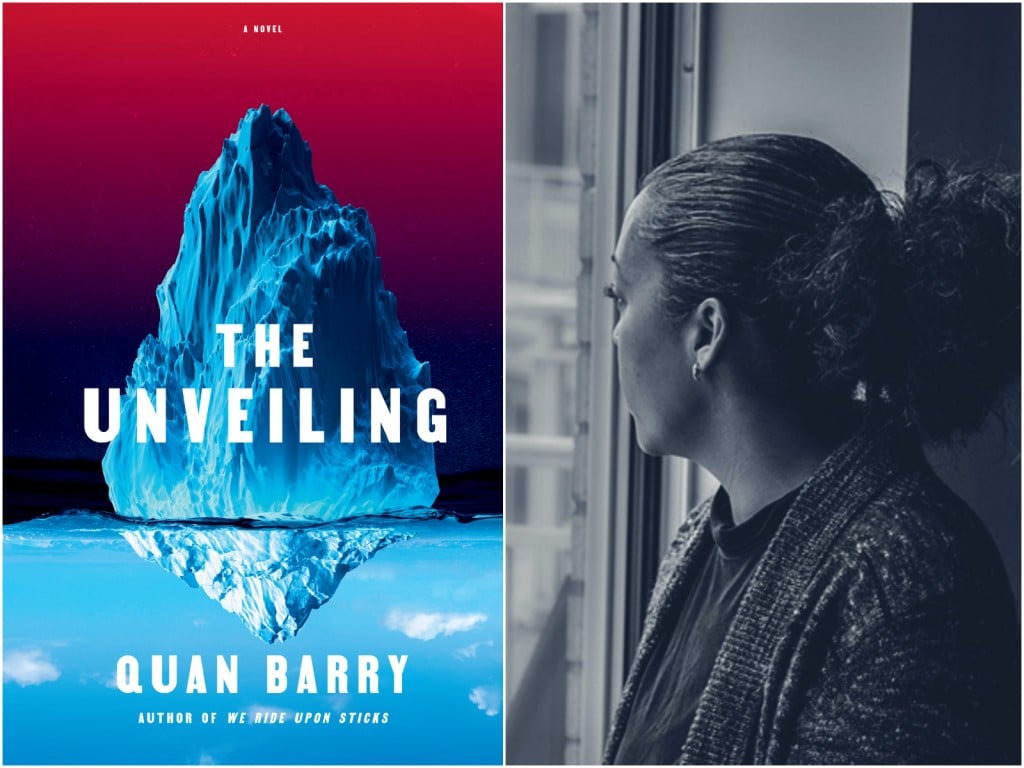

Quan Barry’s horror novel, “The Unveiling,” mines a deadly South-Pole expedition to explore America’s ongoing racial haunting.

While the country around her descended into fascist chaos, Madison author Quan Barry turned to the horror genre for the first time, despite not usually preferring to read or watch horror herself.

“For me, genre books—sci-fi, fantasy, dystopian works, horror, etc.— are the right vehicles for attempting to capture the catastrophe occurring in our country,” Barry says. “A little distance created through extraordinary settings or surreal premises can help the reader engage in the toughest subjects.”

Her latest novel, The Unveiling, is a sharp, hypnotic literary horror novel about a Black woman named Striker who joins a doomed Antarctic cruise alongside a cast of rich white vacationers. Striker’s purpose is to photograph potential filming locations for a movie about Ernest Shackleton, the famous explorer whose boat became trapped in ice in 1915. But when a kayaking excursion goes horribly wrong, the trip takes a terrifying and deadly turn.

While The Unveiling has the hallmarks of a classic horror story—suspenseful twists and turns, shocking imagery, and violent deaths—the novel shines with the nuance, rich imagery, and social commentary that her previous three novels and five poetry collections are known for. Barry expertly uses the icy, white-and-blue landscape of Antarctica—heightened by the 24-hour sunshine of the South Pole’s summer—to intensify Striker’s separateness as the only Black person on the expedition and, probably, the continent.

While Striker must learn to navigate the unfamiliar terrain of Antarctica, she must also navigate majority white spaces, a skill honed over a lifetime. Her biting internal dialogue provides a nuanced commentary on post-2020 racial dynamics. When Striker first introduces herself to the other members of the group, she comments on how race relations have changed since George Floyd’s murder and the eruption of protests that followed—and not necessarily for the better.

Was it her imagination, or were the adults leaning in, eager to hear her every word? This was a new phenomenon Striker had noticed ever since 2020 when pandemonium rightly broke out in the streets. A certain breed of white people attempting to make space. Acting like you had their ear. Like they actually cared what you had to say.

Striker goes on to say, “2020 had made everything worse.” The rebuke feels particularly relevant in a place like Madison, where even though Black Lives Matter protesters swarmed the Capitol and murals by Black artists covered the walls of State Street in the spring and summer 2020, Wisconsin continues to rank lowest in the nation for racial equality. These challenges have come into even sharper focus since Trump took office again, though Barry finished writing the novel before his second term began.

Barry says that she wanted to write a book that implicates not just the worst examples of white people behaving badly—the Karen who calls the police on a Black birder, for example—but all white people, including the progressive ones. Madison readers will likely recognize their city in the book’s commentary. In one remembered conversation between Striker and her best friend in the book, Barry writes about the post-2020 “Great Blackrush,” when companies eagerly hired Black professionals without giving them the support to succeed—a phenomenon Barry says she noticed in some of Madison’s civic and artistic institutions. “When you never had a proper pipeline in place,” Striker ruminates in the novel, “a truly equitable ladder where the cream could rise to the top as they learned the ropes, you ended up with folks at the table who didn’t fully understand the trade through no fault of their own.”

Conversations about race, much like this one early in the novel, suggest that The Unveiling might use horror elements to condemn racism at a societal level. In many ways, it does, but the story takes several surprising turns to dive deeper into Striker’s personal racial traumas. Barry expertly changes the reader’s perspective on Striker by sprinkling details about her past bit by bit—her experience as a transracial adoptee, in particular—to send the reader on a journey that is simultaneously broad and personal.

For Barry, the novel’s explorations of both big-picture and personal racial trauma build on the novel’s main theme: “America’s ongoing racial haunting.” This horror stems from the United States’ history of slavery and its unwillingness to reckon with that shameful history. As Barry explains via email, “To me, all other issues are just gradations of this; racism, Striker’s trauma, class elements—they’re all just different sides of the same coin… We cannot transcend the horrors of our past, which continue to afflict us. Simple as that.” Striker cannot transcend the horrors of her own past until she faces them. And until she does, the world around her will self-destruct in terrifying, horrific ways.

Though Trump’s name does not appear in the novel, the chaos and cruelty of his administration does leave its mark on the story. Barry says that she’d originally thought of writing a Lord Of The Flies-style adventure book, “but after George Floyd was murdered and the first Trump term showed us some hard truths about ourselves, I realized it would be a lost opportunity if I just wrote an entertaining page-turner that didn’t touch on larger issues of social justice.” She began writing The Unveiling in 2022 and found she kept having to add things to it after her original deadline passed as new, horrifying events made their way into the headlines.

In many ways, the turmoil of living through the second Trump term mirrors the disorientation that Striker experiences as her predicament in Antarctica becomes increasingly dire. For example, the entire story unfolds over one never-ending chapter, representing the seemingly never-ending summer day, which causes Striker to lose sense of time.

Time either passed or it didn’t. Overhead the white-hot smudge remained stuck past noon. Though she was standing upright in the swirling mist, Striker couldn’t be sure she was awake. Her mind felt slushy. There was even a name for this kind of disorientation. White torture.

White torture, Striker recalls, is a method of imprisoning someone in a white room, dressing them in white, feeding them white food, and using white lights to eliminate shadows, “their brains softening into a white paste.” Surrounded by white people and miles of ice and snow so white it can cause blindness, Striker becomes disoriented, suffering lapses in memory where sections of narrative are skipped over, and both Striker and the reader must figure out what they’ve missed. For Americans living through Trump’s second term, taking even a one-day break from the news can feel like one of Striker’s lapses in memory, where we wake up, look around, and wonder how we got here.

“Back in 2020, I thought I knew what it was to feel like a character living in a horror movie,” Barry says. “Sadly, I know that the feelings I had back then were nothing compared to now.”

The Unveiling launches on October 14, 2025, with Grove Press. That same day, Quan Barry will host a presentation as part of the Wisconsin Book Festival at 7 p.m. at the Central Library in community rooms 301 and 302.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.