Secrets of Science Hall, part two

Syphilis, sleeping sickness, and the casualties of a hunt for a cure.

Syphilis, sleeping sickness, and the casualties of a hunt for a cure.

This is part two in a three-part series. If you have not read part one, you’ll find that article here.

Patients 100 years ago had few of the rights we take for granted today. In the United States, the principle of patient autonomy was not legally established until 1914. Even then, the notion of informed consent remained rather vague until 1957, when a court ruled that physicians could be held liable for failing to disclose information necessary for a patient to make an informed decision about a medical procedure.

Internationally, awareness of this issue followed the famous 1946-47 trial of Nazi physicians accused of torture and murder while conducting experiments in German concentration camps during the Second World War. The American judges presiding over the trial developed the so-called Nuremberg Code, which articulated 10 principles related to the ethical treatment of human subjects, including the principle of informed consent. The code went beyond the traditional Hippocratic Oath governing the patient-physician relationship to encompass the practices of medical research and experimentation. The Nuremberg Code serves as the ethical underpinning for laws, regulations, and guidelines for scientific and medical associations worldwide.

But all of this was in the future in the first decades of the 20th century, when researchers were experimenting with atoxyl and other drugs for sleeping sickness. It is true that these compounds would generally have been tested on animals before humans. Animal research helped researchers assess not only the promise of a new drug, but also its toxicity levels. It is also true that Europeans—those who had contracted sleeping sickness while in the tropics—served as guinea pigs in clinical drug experiments. But colonists and researchers saw Africa as an opportunity to conduct experimentation on a scale undreamed of in Europe or the United States before this time. And it was African people who served as the human fodder for these medical experiments, eclipsing all other groups in terms of the total number of patients and the variety of drugs tested.

European racial attitudes greatly intensified the chauvinism of the medical establishment toward the patients they were supposed to be serving. This was an era in which racialized theories like eugenics and phrenology permeated scientific and popular thought. Even highly educated individuals would have considered Africans to be primitive, uncivilized, and desperately in need of western medicine. Africans would have been seen as unaware of their own culpability in their ill-health and, to make matters worse, reluctant to do anything to improve it. Physicians at the time described them as “bad patients” unable to undergo a prolonged course of treatment, incapable of tolerating pain, possessing no endurance, and likely to disappear before treatment was complete.

These attitudes and ideas meant that European physicians would have had little trouble adopting authoritarian approaches rather than trying to understand and work within local customs and beliefs. European researchers effectively treated the local population as a tabula rasa, a clean slate, whose sole purpose was to supply the human material needed for drug experimentation

In the early 20th century, researchers knew that arsenicals (compounds that contain arsenic) had a therapeutic effect on sleeping sickness and they began to study these compounds intensively.

One such compound was atoxyl, originally synthesized in France in 1859. At first, researchers heralded atoxyl as a miracle cure. For example, Sir Rubert Boyce, professor of pathology at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, stated in a 1907 volume of the British Medical Journal that tropical medicine experts gave atoxyl “the premier position as a trypanocide.” He boasted that the Liverpool School “has sent out, free of charge, large quantities of this hitherto somewhat expensive drug to medical men and missionaries in West Africa.”

It soon became clear that atoxyl was far from perfect. Some of the first warning signs appeared when Robert Koch, the eminent German scientist and Nobel Laureate, began to experiment with the drug in Africa. Koch is probably best known for his discovery in 1882 of the bacteria responsible for tuberculosis. An early advocate of atoxyl, Koch traveled to German East Africa on a scientific mission in 1906-07, where he tested atoxyl on thousands of individuals exhibiting both early and advanced symptoms of sleeping sickness.

By today’s standards, Koch and his colleagues in Africa had a stunning level of freedom to conduct their experiments—they can hardly be called trials or therapy—free of independent oversight. According to contemporary accounts, Koch’s approach deviated from the normal method of slowly increasing dosages and instead experimented with different doses and intervals for administering the drug. Some patients received smaller doses over different intervals of time, but some received one large dose. The idea behind the larger dose was to obtain a more lasting result, since the drug’s benefits tended to be short-lived. Unfortunately, this had the unintended side effect of causing the rapid onset of permanent blindness in both eyes. The larger doses were reportedly stopped, but the damage had already been done. Other physicians working in Africa observed similar effects of high atoxyl dosages, including eye lesions diagnosed as atrophy of the optic nerve.

In reports of his East Africa expedition of 1906-07, Koch stated that treatment was officially voluntary and free of compulsion, yet at the same time he yearned for a time when physicians would be able to insist on a course of atoxyl treatment for each patient.

In addition to atoxyl, Koch tested several other arsenicals on his human patients, including sodium arsenate (which is listed as a hazardous material by the U.S. government) and several patent medicines. He also injected patients with a number of staining compounds (dyes), including trypan red, afridol blue, and afridol violet, all inventions of the German chemical industry. The injection of the dyes was reportedly so painful they could only be administered in small doses. Some of these dyes, such as trypan red, had not even been shown to be effective in experimental laboratory trials on animals.

On his return to Germany from the expedition, Koch advocated for the establishment of camps where infected individuals could be isolated. This idea was later implemented in Germany’s western African colony of Togoland (now the nation of Togo). Elsewhere in Africa, colonial administrators enacted authoritarian public health measures, such as forced relocation and segregation, obligatory medical examinations, medical passports, restrictions on activities and travel, enforced quarantine and isolation, and limitations on social and familial interactions. Such measures were not unique to Afrcia however, having been developed in Europe in response to plague and cholera epidemics. Nor are these measures necessarily seen as obsolete by public health experts, with many of the same approaches being used around the world in recent times for influenza and similar diseases.

The immediate problem facing Koch, however, was atoxyl itself. Even if damage to the eyes and optic nerve could be avoided by lowering the dosage, it did not change the fact that the atoxyl trials in German East Africa were anything but a resounding success. Initial elimination of the pathogen in patients—which was facilitated by the relatively high doses Koch injected—did not generally translate into lasting cures. Medical reports from the period show a high rate of remission, many patient fatalities and a tendency for patients to disappear to avoid further injections. If Koch was to find an effective sleeping sickness cure, a new approach would be needed.

Progress on syphilis treatment

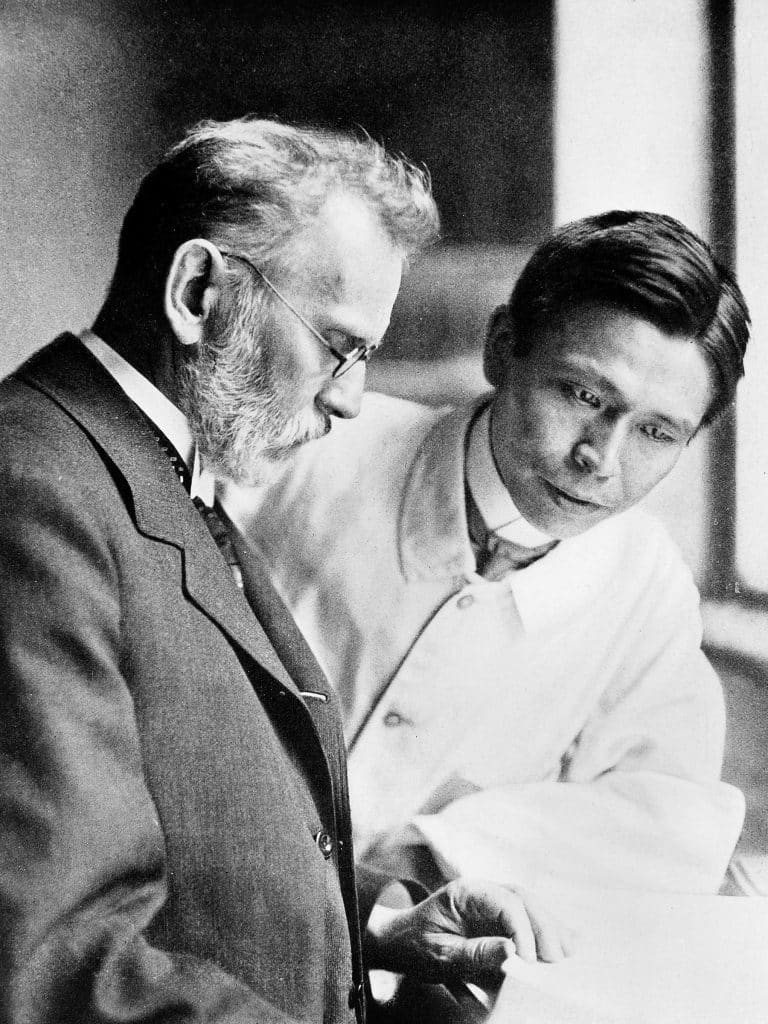

In late 1907, when Robert Koch returned to Germany from his African expedition, he began searching for an alternative to atoxyl for treating sleeping sickness. He enlisted the help of a protégé, Paul Ehrlich, director of the Royal Institute for Experimental Therapy (now the Paul Ehrlich Institute) in Frankfurt and one of Germany’s most prominent medical researchers. Ehrlich had established his reputation by exploiting the properties of synthetic dyes to develop therapeutic chemicals or “chemotherapies.” His approach was to isolate a dye that would attach itself to a particular pathogen and then join that dye to a toxin that would kill the pathogen. In 1908, Ehrlich was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work.

Ehrlich studied a variety of diseases, including tuberculosis, diphtheria, sleeping sickness, and syphilis. The bacteria causing syphilis—Treponema pallidum—had been discovered in 1905 by German scientists. The early stages of the disease are characterized by lesions called chancres that disappear after a few months, followed by a symptom-free period that can last for years. In the latter stages of syphilis—which can occur decades after infection—organ systems can be affected, including the brain and spinal cord.

By the dawn of the 20th century scientists knew that syphilis and sleeping sickness, while caused by different organisms, both responded to drugs containing arsenic. Due to this unlikely coincidence, advances in the treatment of sleeping sickness often followed from research on syphilis, and vice versa. This is what happened when Ehrlich set to work on a cure for sleeping sickness.

In Ehrlich’s laboratory in Frankfurt, numerous arsenicals were tested on the sleeping sickness pathogen. Results were not encouraging. But in 1909, Sahachiro Hata, a Japanese scientist studying at the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (now the Robert Koch Institute) in Berlin, began to collaborate with Ehrlich in Frankfurt. Hata observed that one of the compounds he tested was effective against syphilis in rabbits. He reported the details of the animal experiments at a medical conference in April 1910. The drug famously became known as “Compound 606” or simply the “Hata Preparation.”

The first human tests of Compound 606 occurred at Uchtspringe, a psychiatric hospital in Germany, where physicians injected two research assistants with the new drug without adverse effects. Later, hundreds of men and women (including pregnant women), as well as children suffering from congenital syphilis, were treated with Compound 606 with great success.

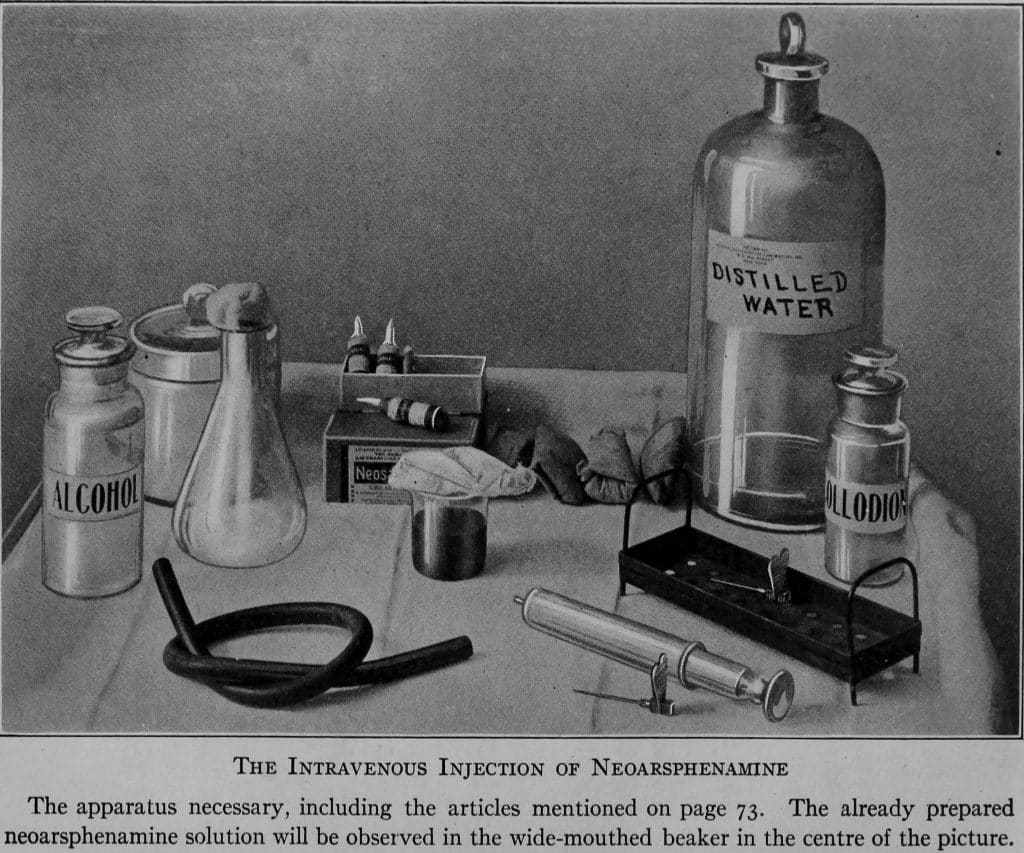

Inoculation with 606 was a complicated affair. It involved mixing the pale yellow powder in a mortar with caustic soda, adding acetic acid to neutralize the mixture, running the contents through a centrifuge, and pouring off the excess liquid. The resulting precipitate is mixed with saline solution, and injected subcutaneously with a syringe having a large-bore needle, being careful to keep the needle sterilized to prevent skin necrosis.

As a laboratory-produced chemical compound and the first truly effective drug for syphilis, Compound 606 marked a turning point in medicine. It remained the most-used treatment for syphilis until the advent of penicillin in the 1940s. The German chemical company Farbwerke Hoechst marketed the drug under the trade name salvarsan. In the United States, it was known as arsphenamine. By 1912, salvarsan had been augmented with neosalvarsan (neoarsphenamine), which was simpler to administer, although somewhat less effective.

While Compound 606 is sometimes described as Ehrlich’s discovery, Ehrlich himself gave most of the credit to Hata, calling his work “brilliant, careful, and meticulously precise.” On returning to Japan in 1910, Hata devoted the rest of his life to eradicating syphilis through education, training and treatment. He promoted the use of Compound 606, helped develop a domestic version of the drug when imports were interrupted during the First World War, and was the first to advocate for screening and treatment during pregnancy to prevent congenital syphilis.

Loevenhart‘s research

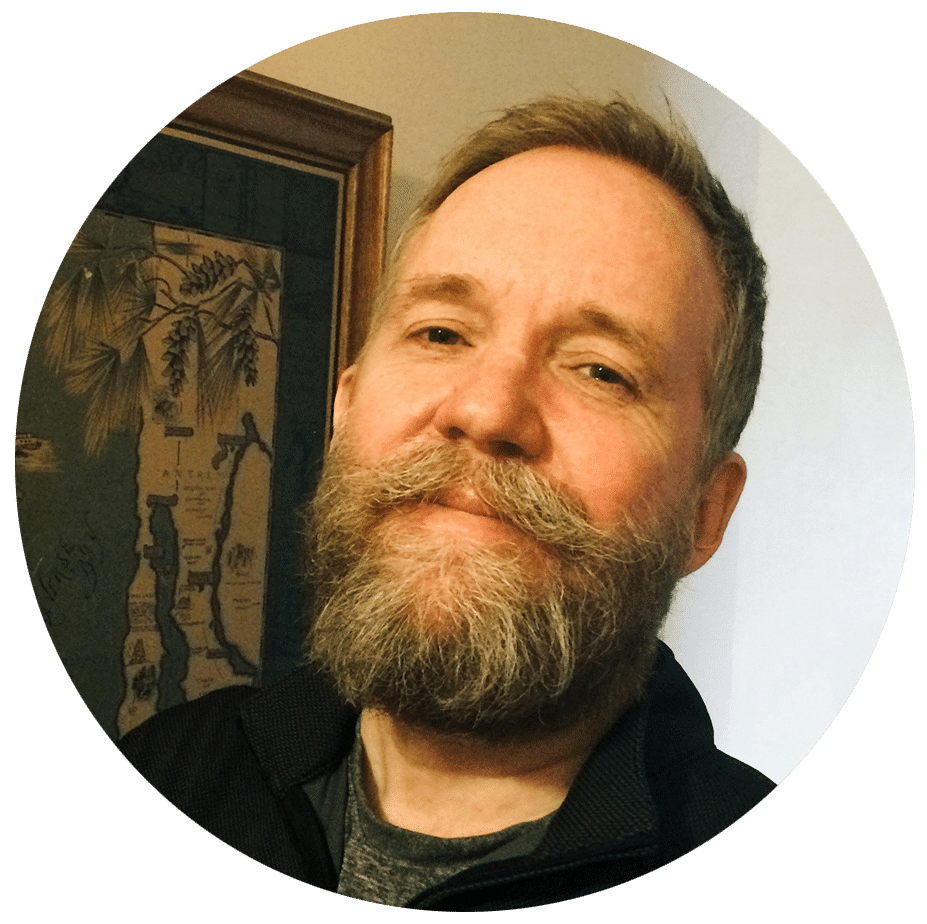

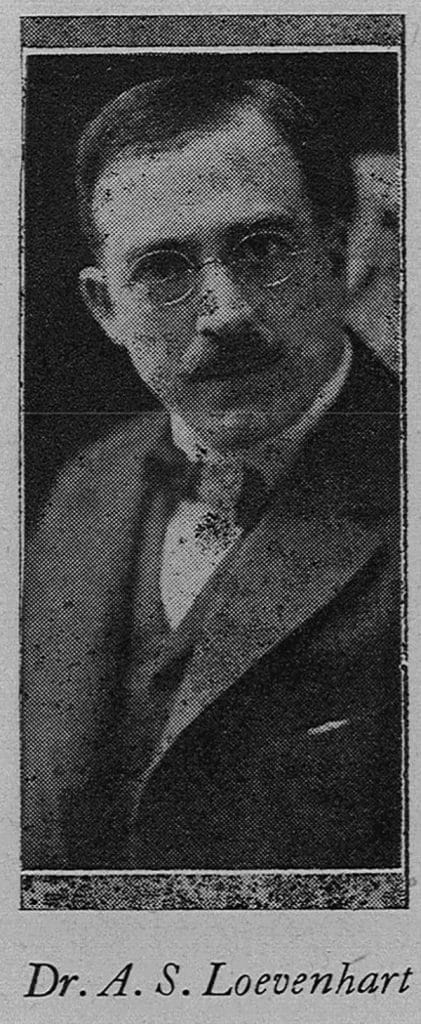

Arthur Loevenhart came to the University of Wisconsin in 1908 to establish the department of pharmacology and toxicology. According to R. W. Wilcox’s encyclopedic textbook, Pharmacology And Therapeutics—the seventh edition of which was published in 1907—pharmacology was the study of the therapeutic properties of medicines and their application in the treatment of disease. Toxicology involved the examination of poisons, including their effects, detection, antidotes and treatments. This field suited Loevenhart well, given his background in chemistry and his M.D. degree.

When Loevenhart arrived in Madison, his department was housed in the Chemical Engineering building, built in 1885 but demolished in 1965 to make way for Helen C. White Library. Loevenhart used the attic of Chemical Engineering for animal experimentation, including keeping animals at low oxygen levels for long periods of time to study anoxemia. The entrance of the United States into the First World War in 1917 led him to conduct experiments on animals to assess the effects of poison gases. According to his colleague H. C. Bradley, Loevenhart took his turn on night shifts in the Chemical Engineering building attic, where he would be roused each hour by an alarm clock to log the symptoms of the dogs in the gassing chambers.

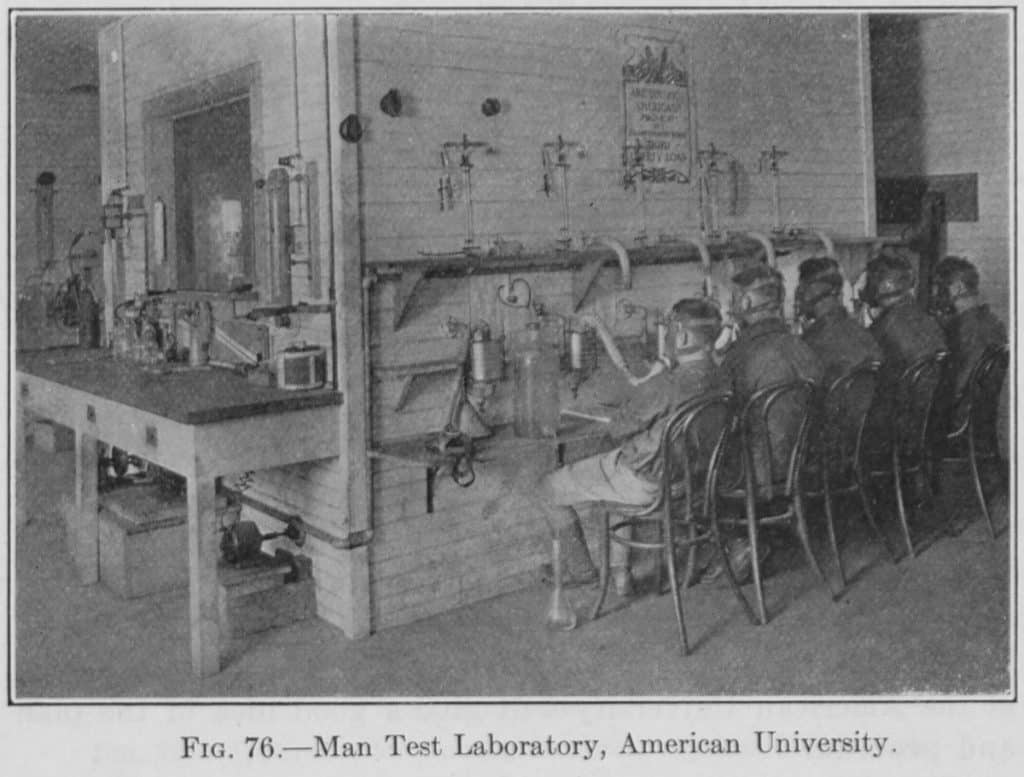

Loevenhart moved his department to Science Hall in 1917, because extra space had been created when the physics department vacated the building. Loevenhart’s apparatus for poison gas experimentation came with him and his dog experiments continued. In 1918, Loevenhart received a leave of absence from the university to participate in chemical warfare research for the U.S. Army. From May 1918 to January 1919, he served as Chief of the Pharmacology and Toxicology Section in the Research Division of the Army’s new Chemical Warfare Service. He spent time in Washington D.C. at American University, the center of U.S. chemical warfare research at the time.

At American, Loevenhart’s division assessed the toxicity of new compounds synthesized in the laboratory. They first experimented on rats and mice and then, if results looked promising, on larger animals like cats, dogs, and goats. Some researchers at American also experimented with chemicals on humans, although it is not certain Lovenhart was involved. He did work collaboratively with Dr. W. Lee Lewis, the Northwestern University chemist who developed Lewisite, an arsenic-based poison gas intended for use on the battlefield. This means Loevenhart would have become familiar with the effects of arsenicals on living organisms, knowledge that would prove useful in his later research.

Loevenhart continued to consult with the Chemical Warfare Service after the war ended. This would have been somewhat controversial, since many scientists and politicians had sought to disband the service in 1919, considering it unnecessary in a time of peace. After the war, Loevenhart received a commendation from the director of the Chemical Warfare Service and was appointed a Major in the U.S. Army in 1925. It was shortly after the war that Loevenhart established his syphilis laboratory in the attic of Science Hall.

Neurosyphilis and psychiatric hospitals

During the 1920s, medical researchers published hundreds of reports on syphilis. Many of these reports focused on finding an alternative to salvarsan (Compound 606), which often required a long and complex course of treatment. In Science Hall, Loevenhart tested compounds created by chemical laboratories at other universities, medical institutes, and private companies. One of these compounds was tryparsamide, an arsenical developed in 1915 by scientists at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, one of the first biomedical research centers in the U.S. Tryparsamide was one of three drugs supplied by the Rockefeller Institute when Loevenhart, in 1919, wrote to request samples of substances that might be useful for treating neurosyphilis.

Neurosyphilis occurs when the syphilis bacterium invades the central nervous system. In its later stages, the manifestations of neurosyphilis can be severe, including tabes dorsalis (degeneration of the spinal cord) and general paresis (dementia associated with advanced infection of the brain, also once known as general paralysis of the insane). In Loevenhart’s time, neurosyphilis was nearly impossible to treat. Salvarsan, for example, was ineffective against it. Paresis was a death sentence where the patient lost control over the mind and body, sometimes to the accompaniment of grandiose delusions. A century ago, patients suffering from paresis would have made up a significant proportion of the population of psychiatric hospitals.

Neurosyphilis was also difficult to study because it did not manifest itself in experimental laboratory animals the way it did in humans. And even if it did, the limited lifespan of a typical laboratory rabbit and the fast pace of medical research would have made it difficult to observe the progression of the disease. Neurosyphilis had to be studied using human subjects.

For Loevenhart, this was accomplished through his relationship with William F. Lorenz, a faculty member in the medical school’s department of neuropsychiatry. Born in Brooklyn in 1882, Lorenz received his M.D. from the New York University School of Medicine in 1903 and joined the University of Wisconsin in 1910. In 1915, he became the first director of the Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute.

The Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute was initially a research unit of the Wisconsin State Hospital for the Insane, located across Lake Mendota from the university at Farwell’s Point. The State Hospital was established in 1857. The main building opened in 1860 and survived until the 1960s. The hospital is now known as Mendota Mental Health Institute. Shortly after the First World War ended, Wisconsin began to look for ways to provide for the psychiatric treatment of veterans, which led to the creation of Wisconsin Memorial Hospital on the grounds of the State Hospital for the Insane. Memorial Hospital was designed specifically for the treatment of “nervous and mental cases” in veterans of the First World War and according to Lorenz it was “devoted to the exclusive purposes of the Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute.”

By the early 1930s Memorial Hospital housed almost 300 patients and employed about 125 staff. In addition to the hospital building itself, the facility included patient dormitories, staff quarters, administration buildings, a dining hall, a chapel and other structures, all adjacent to several clusters of Native American mounds. Many of these structures and some of the mounds remain today, although the hospital building has been vacant for decades.

Loevenhart and Lorenz began their neurosyphilis collaboration in 1919 and first published their results in 1923 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Loevenhart focused on the pharmacology, while Lorenz led the clinical research on human subjects. By the standards of the time, their results were groundbreaking and they are considered to be the first researchers to demonstrate the effectiveness of tryparsamide—usually used in conjunction with other chemicals, such as mercury salicylate—for treating neurosyphilis. The pair conducted research on hundreds of subjects, both out-patients and those who had been committed to a psychiatric institution. Treatment often took several years.

Their results were optimistic. They reported that many institutionalized patients were eventually discharged and were able to earn “a livelihood for themselves and their families for periods ranging from six months to two years.” Other researchers took notice, as did the Rockefeller Institute, which made tryparsamide available to other research institutions across the country. Subsequently, enthusiastic reports on the effectiveness of the drug were reported by researchers the Mayo Clinic, the University of Michigan Clinic, Massachusetts General Hospital, and others.

Not the cure it seemed

It is wise to be at least a bit skeptical about the findings of Lorenz, Loevenhart, and the researchers who followed them. Early clinical work seemed to demonstrate the effectiveness of tryparsamide, but in fact success with the drug was never certain. Lorenz found that variations in therapeutic procedures—amount of drug given, duration of treatment, interruption of treatment, addition of mercury, addition of other arsenicals, etc.—were not consistently associated with a greater likelihood of success. By the 1940s, especially as the use of antibiotics became more widespread, medical researchers began to question the value of the drug.

The problem stemmed in part from experimental designs that did not account for patients’ previous syphilis treatment histories, as well as the concurrent use of medicines containing mercury or bismuth, all of which made it difficult to untangle tryparsamide’s actual benefits. In contrast, the more rigorous standards applied to clinical testing of penicillin clearly showed the antibiotic to be both effective and safe. Tryparsamide may have been the drug of choice when no other options existed, but with the introduction of antibiotics its limitations became hard to ignore.

Another mark against tryparsamide was its effects on vision. High doses of the drug caused blindness and semi-blindness in several Wisconsin patients. Such risks were generally seen as acceptable at the time, given the reported efficiency of the treatment. This does not mean that medical researchers were oblivious to the ethical problems involved in their work. For example, Loevenhart insisted on animal experimentation before human tests, in order to assess drug toxicity. Then, if a chemical was found to have therapeutic value, it was administered to laboratory workers and the lab director before being submitted to the clinical team, in order to determine its rate of excretion and possible side effects. For clinical trials, Loevenhart emphasized the importance of the pharmacologist, whose role included looking out for the interests of the patient.

Counteracting this humanitarian concern was the tendency for administrators and government officials to focus on the economic costs of disease. For neurosyphilis, the cost of caring for patients confined to state psychiatric hospitals was frequently cited as a justification for finding a cure, as this would allow patients to be discharged and reduce costs. By the mid-1920s, observers were noting that Lorenz and Loevenhart had saved Wisconsin as much as $800,000.

Focusing on economic benefits may have also been a strategy to short-circuit public distaste for syphilis research. Syphilis was associated with socially inappropriate behaviors such as sex outside of marriage and some felt that syphilis victims deserved their fate. Sensitivity to public opinion may be what led the Regents of the University of Wisconsin, in a 1929 resolution marking Loevenhart’s contributions to medicine, to avoid using the word syphilis altogether. Instead, the resolution described Loevenhart as “a humanitarian, a healer of men, who stayed the drop of the black curtain of mental oblivion for many a tainted and tortured social derelict.” In this capacity, Loevenhart “forgot his loathing for their sin” and sought “not to judge, but only to cure.”

Despite these moral qualms, from a public health standpoint the timing was right for an anti-syphilis program. In response to the high rates of the disease in the ranks of returning servicemen, the federal government established the Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Board in 1918 to allocate funds to conduct research and treatment on venereal disease. Loevenhart received a $6,000 grant from the Board in 1919. More controversial was a second grant of $12,500 he received in 1925 from the General Education Board. The Board had been established in 1903 with a one-million-dollar gift from John D. Rockefeller. A few decades later, by the early 1930s, the Board had donated almost $60 million to US schools and colleges to support education, medicine and agriculture.

Gifts were a small percentage of the University of Wisconsin’s budget in the early years. By the 1920s, however, contributions had started to increase as the university grew and programs diversified. Not everyone approved of the practice. One of the more vocal critics was Robert La Follette, U.S. Senator for Wisconsin and former governor of the state. La Follette argued that corporate sponsorship posed a threat to academic freedom and the university’s role as an independent arbiter of truth. La Follette’s relationship with the university was of course already fraught with controversy. In 1917, the university’s faculty and students formally censured him and then hanged him in effigy over his efforts to keep the country out of the First World War.

When the Regents voted to accept Loevenhart’s $12,500 grant, a storm of controversy erupted involving labor unions, elected representatives, and the newspapers. Of particular concern was the fact that the gift originated from the Rockefellers, the epitome of gilded age capitalism. To avoid further censure, the Regents passed a resolution in August 1925, debarring the university from accepting any funds from endowed educational corporations. This in turn sparked an outcry from faculty and alumni, who thought this would strangle the university. Despite the resolution, the Regents continued to accept gifts from other entities but avoided the General Education Board and other funds originating with the Rockefellers. The August 1925 resolution was finally rescinded in 1930.

Greater controversies were to come as Loevenhart and his students began to extend their research to sleeping sickness. In the post-war era, the search for a sleeping sickness cure had significant geopolitical implications, due to the competing colonial aspirations of European nations. Africa became a battleground in the race to find a cure, and researchers from the University of Wisconsin became players in this drama.

Coming in Part 3: The development of Bayer 205, the first successful treatment for sleeping sickness; Germany’s attempts to leverage the drug to regain its lost African colonial empire after the First World War; The race to develop alternatives to Bayer 205; The growth of US commercial interests in Africa; Sleeping sickness research at the University of Wisconsin by Loevenhart’s student, Warren Stratman-Thomas; The university’s sleeping sickness expedition to the Belgian Congo; The aftermath of the Congo expedition; The unraveling of Loevenhart’s plans; Sleeping sickness and neurosyphilis today; Africa’s colonial legacy.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.