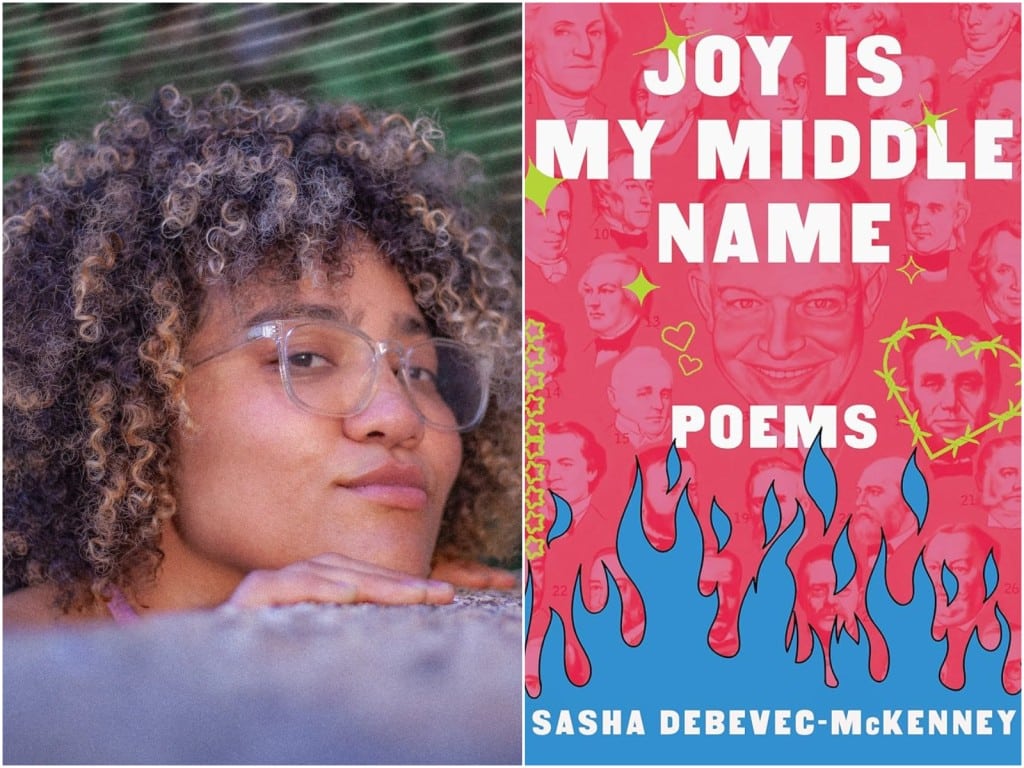

Sasha Debevec-McKenney catalogs a museum of her 20s in “Joy Is My Middle Name”

The formerly Madison-based poet gives justice to our city and the richness of girlhood in this debut poetry collection.

I picked up Joy Is My Middle Name, Sasha Debevec-McKenney’s debut poetry collection, during a time in my life when things kept going cosmically wrong. Freshly 28, I was confronted with a record-breaking number of tragedies over the course of two weeks, including but not limited to: a sudden breakup, an ailing cat, and a 3,000-mile cross-country move that I was now tasked with doing alone, thanks to the aforementioned breakup.

The magnitude, force, and quick succession of these events made it so that I began to question what an old self could’ve possibly done to deserve this kind of karmic retribution. I didn’t crack open Joy Is My Middle Name expecting to find the answer, but almost immediately, I found an answer, or perhaps a mere suggestion: In the opening poem, “Cento for the Night I Tried Stand-Up,” Debevec-McKenney writes, “You can spend / a decade on the wrong thing, / and before you realize it, / it’s too late.”

I paused, underlining her words, and considered if this were the case with me and my 20s. (The jury is still out.) I’d have this kind of reflection many times as I read the collection, which is part diary, part survival guide, part American travel guide, and indeed, part stand-up comedy routine. Joy Is My Middle Name is an unflinching account of what it means to survive your 20s, to live in a body made to contend with Western ideals of beauty, biraciality, the perception of others, and the historic forces that shape all of these things.

Spanning everywhere from small town Connecticut, to the gravesites and homes of former U.S. presidents, to our beloved Madison, Wisconsin, the pages of Joy Is My Middle Name showcase an introspective, fun, and sobering array of meditations on a decade of personal tragedies of heartbreak and addiction, written alongside the macro-histories of slavery, Reconstruction, and the spectres of racism that haunt our country today.

Shifting from earnestness to dry humor, sometimes in the very same line, Debevec-McKenney has a knack for turning rich national histories into the mundane (“Sometimes history is as simple as that”), while building monuments to moments that others might view as ordinary (“Joy the first time I stepped inside a frat house, a real frat house, and it was so / like a movie I thought maybe the whole world wasn’t a lie”).

If the speaker demands to be seen, and seen completely (“Now all I want is when I make a mistake / for everyone to say, ‘Oh Sasha! Her mistakes / are so spectacular we can’t seem to look away!'”), it is for good reason: As Debevec-McKenney reveals in conversation, it’s rare that we ever get to read everyday women of color stumble through the blunders of their 20s, coming out the other end not unscathed, but somehow, wiser. Even in the darkest moments of the book, Joy Is My Middle Name oozes with a lust for life and others (“Outside, the lake was freezing. I didn’t want to freeze with it”)—the kind of stubborn optimism necessary to survive a world seemingly stacked against you.

In early October—ahead of the 2025 Wisconsin Book Festival event in conversation with Chessy Normille on Friday, October 24, at 9 p.m. in the Central Library’s third floor community rooms 301 and 302—I spoke with Debevec-McKenney over Zoom to discuss girlhood, Americanness, and experiences worth writing about.

Tone Madison: If you could be eating a cone of Chocolate Shoppe ice cream for this interview, what would it be?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: Did you know that I worked at Chocolate Shoppe? That was my first job in Madison. I worked at the Chocolate Shoppe on State Street and I had a crush on this guy that worked at the Pita Pit [also formerly on State]. It was a very special time in my life. Off the top of my head, without looking, I always loved Yippee Skippee (with pretzels), that was really important to me. And the summer that I got hired was the summer they did This $&@! Just Got Serious, and now I feel like she’s a staple. I was there at the beginning.

Tone Madison: I learned the art of long titles from you. Some of them are leading titles, but others seem almost separate from the body of the poem itself. Could you talk a little bit about this creative choice and what it allows you to do?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: I’m a big proponent of, “Whatever it is, it can go in the poem.” I don’t really like epigraphs that much. I really hate when I go to a reading and the person talks for five minutes and then reads the poem. I’m like, “If you can’t put it in the poem, don’t write the poem.” So for me, I’ll use the title as a way to get us all on the same page. I really want my audience to be engaged from the beginning, so that you can trust me, and I’ll carry you through the poem. The title is a chance to bring the audience on board, but it’s also a place where you can just give information that maybe isn’t that poetic. All the time I’ll have an idea, and the only way for the idea to make sense is if I just tell you exactly what the poem is about in the title. And I’m always so disappointed when the title is really good and the poem is bad. So I like to have a good title, but then I try my hardest to make good on that.

The book was with Fitzcarraldo before it was with Norton, and the original title for the book was just Poems because I thought it would be funny that the titles of the poems are all full sentences and the title of the book is one word, very dull and boring. But then Norton said that you couldn’t Google [Poems]. So yeah, I like to think of titles as a headline, just a place for information, a place to say hi.

Tone Madison: One of the things you write about and are fascinated by is U.S. presidents, and there are many poems of you visiting grave sites, museums, and monuments. Do you in any way consider yourself a historian?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: I used to always put that in my bio: “wannabe historian.” No, because I don’t do research that much. I’m really just writing about how I feel, or using it as a way to enter another feeling. I feel really safe and comfortable writing about American presidents, writing about American history, but I feel less comfortable writing about my feelings. So it’s a way in a lot of times for me. During my sophomore year of college, I went on a trip where I visited all these [pre-Civil War] presidents’ graves and homes. And these are all men who are like, “We’re compromising!” “I’m going to save the Union!” “I’m gonna be famous forever!” “There’s never gonna be a Civil War!” and then there’s a Civil War anyways, like five years later. And the things that they were compromising were enslaved people’s lives.

And so I went on these trips, and one of the houses that I went to is the Franklin Pierce Manse. There’s a poem about this in the book, and I just had this really tough conversation with this woman where she was like, “Oh, you know, Pierce saw the quality of life of freed people and he saw that they would have a better quality of life as slaves.” And I was like, 20 years old, or maybe even 19. And I was just so confused because this woman was an elementary school teacher, she was running all the tours, and I just couldn’t conceive of all the damage she had done in the name of preserving his legacy. I sent my professor Beatrice an email, and I was like, “I’m freaking out. I don’t know what to do with this.” And she was kind of like, “The historians who don’t answer these questions and the people who don’t question the information that’s given to them, those are not real historians.” So I don’t think of myself as a historian, but I do feel like part of something that I’m interested in is questioning history. And I feel like, [for] a lot of people, that makes them uncomfortable, and for good reason. It’s not pretty.

Tone Madison: I was really struck by “Sestina Where Every End Word is Lyndon Johnson,” and particularly the lines: “[…] And I think that’s all Lyndon Johnson / ever wanted: for us to believe no one like Lyndon Johnson / exists, or existed. […]” To me, this speculation rings true for girlhood, and young womanhood, which is so much of what this book is about. Do you see similarities between the singular experiences of being a president and being a girl?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: I like this reading because I hate this poem so much. I think it’s kind of corny and cheesy, but I think in the context of the book, it’s okay because the book is so much about obsession and being bad and addictive. I’ve been obsessed with presidents since I was a little girl. My whole life, it’s been something that I’ve been interested in. Your experience of learning history as a child is fun facts and little things that are gonna soften you towards these people. Then later, if you’re lucky, or if someone teaches you, you could learn the truth, but I feel like I wouldn’t want to sully the beautiful thing that is girlhood by comparing it to the disgusting thing of being a president.

I think girlhood is the most beautiful thing in the world. I was on the train last week, and there were these really drunk girls that were listening to Adele and screaming “Someone Like You,” and they were so wasted. And all the men around me, everyone was looking at each other. I had gotten a little baby bottle of wine at the train station, and I took one sip, and it was so sweet I didn’t want it. And I was like, “Should I give this to those girls?” And they were like, “Absolutely, we want this.” And I feel like I have moments every day where I feel connected to a girl, or I compliment a girl on her hair, or she tells me my dress is pretty. It’s not that we owe each other, but I did a thing the other day where somebody said, “As the violence and the people telling us to hate each other gets more and more intense, the tenderness has to rise to that level too.” I do feel like I have to walk through the world and be kind to people. I feel like that’s how [presidency and girlhood] are related. One thing helps us survive the other thing.

Tone Madison: There are a lot of poems in which others are witnessing you in your poems, along with your anxieties about being witnessed—I’m thinking in particular about “Sample of Myself.” Could you talk a little bit about poetry as self-witness? What role does hindsight play in this?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: People think that poetry is nonfiction, but it’s really so much to me about crafting a little story. Obviously, my poems are pretty narrative, so that’s how I see it. Not that everybody writes like that. I think I appreciate a place where you can be honest about how you feel and honest about not being perfect. The poems I like are poems where people show an ugly side of them or a truth about them—even if it’s not true. When I look back at the book, I feel really sad for her in some ways. But I’m also like, “We made art out of that, so that’s kind of cool.”

I don’t think about things in terms like that, you know what I mean? I’ve never considered the phrase “self-witness.” I’m just like, “Well, I’m writing about myself.” That’s how I think about everything. I always tell my students that it’s so powerful to, in the face of everything, believe that you seeing a leaf is important enough to write down. When I look at this book and I think about when I read it for the first time, I was very much like, “Oh, this is so much more about drinking and addiction than I thought it was.” But I feel like that’s one of the things that is most difficult for me to understand about myself. So it’s the thing I wrote about the most, because I wish I could fix it or change it, and I can’t. I feel really lucky because I think of it more as a museum. I can read back the poem about Johnny [“Johnny Teaches Me How To Use A Power Drill In Reverse”] and feel how I felt. I feel really lucky to have those pieces of myself and have those moments that I crystallize, but I don’t think they’re necessarily true. They’re synthesized through my brain and they’re made into a neat thing.

Tone Madison: I feel like there’s also a sense of you looking after younger selves, like in the poem that ends, “We weren’t safe / on the bike path, / there should have been / more light.”

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: That is such a Madison poem. I feel like that’s 10 years, seven years or whatever, condensed down to 10 lines. Every single one of those little moments in that poem has a clear, specific image for what I’m talking about, but I’m not letting all of that in. I’m thinking about having to live for seven years on the East Side to write a line. Something I like about the book is that, I feel like you usually read a poetry book and it has one beloved. And my book has a poem for every guy I hooked up with for like, six months or whatever. And there’s a big relationship that’s not in the book at all, except for that line “losing condoms inside us,” which is referencing something that happened with that person. And I think someone might read the book and be like, “Wow, she’s so confessional,” or “She’s telling all her secrets,” but there’s so much that’s not there.

Tone Madison: It’s a beautiful testament to your 20s.

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: Yeah, and it’s nice to be like, “That’s important. I’m putting it in a poem.” Being a girl is important, making mistakes is important, getting your heart broken… all that stuff is worth writing. I struggle with that because I feel like there’s so many times where the only work that people want to read from me is the work that’s about presidents or about race and identity. I don’t feel sometimes like my work is valued if it’s not serious. I like this idea of self-witness, of “Here are these little moments that are important. I want to remember them and I want to connect to somebody else through them, because maybe they experienced the same thing.”

Tone Madison: Some of the poems in this book are framed as stand-up routines. What do you find to be the function of performance—of the body, of poetry—in your work?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: Going back to the thing I was saying about titles, I started writing in high school workshops because I went to an arts high school in the afternoon. If you wrote the best poem, you would perform it at the end of the semester. I genuinely feel like I’ve never had a relationship with poetry that doesn’t involve an audience, whether it be a workshop, whether it be, “I want to be the best so I can read to everyone and my parents will come and be proud of me.” And I just feel like I love reading my work out loud. I go to so many boring poetry readings where people can’t read the room, and they’re reading really slowly to inject meaning into a shitty poem. I really feel like, for me, a poem belongs to the audience too. I really, really want people to understand what I’m saying. I want people to laugh. I want people to be with me when I’m reading, to not be bored. I really like my audiences, whoever they are, even if it’s just the people that follow my secret Instagram that I post my poems on sometimes. I want someone to be held. I think that sometimes we don’t value making people laugh as something that’s difficult to do. If I’m working on something and I can’t really figure it out, I’ll record it and listen to myself read it over and over. Or I’ll literally walk around and read out loud. I think poetry is a place to be selfish and write about whatever you want, and do whatever you want. I choose to consider my audience, and I don’t think some people do that.

Tone Madison: In the spirit of reporting for a Madison publication, I feel like I have to ask a Wisconsin question. Some of your poems make pretty obvious references to the city, but they aren’t exactly glamorous or pastoral—some include anecdotes about working service jobs, racist interactions, and even local scandal. I’d love to hear your thoughts on what it means to give justice to a place by writing about it.

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: I feel like Madison is my favorite place on earth. Everything that’s ever happened to me happened there, and I’ll always think of it very fondly. I think Madison’s in the book a lot because it’s where I lived. But if a poem is a place for your conflict and your confusion, it is the place where I have the strongest confused feelings because I have just been treated like shit there. Whether it be at service jobs or by men or even seeing my friends be treated like shit by people in restaurants that everyone loves. It’s such a weird place but I also just love it so much, and my feelings are complicated and strong, and that’s the place where the poem happens, often.

And I don’t think that my experience of Madison is necessarily everyone else’s, but I also feel like I had so much fun in my 20s. I barely wrote anything for seven years. I just got drunk and had fun and got my heart broken and that’s what I wrote about. There was a part of me that felt like I was wasting my life or my time by not being necessarily productive. And I feel like writing the poems and having the book out makes me feel like that time was worthwhile. Maybe people will read this and maybe not see the Madison that they know, but the people who will recognize the Madison in the book are the people who I want to write the book for or I hope feel good about it. It felt so great because I had the release party at Mickey’s [in August], and all my friends helped set it up, and we were doing Jell-O shots. There were so many people there, my favorite [Willy Street] Co-op customers were there, and it just felt so magical.

I love Wisconsin, my family is from Wisconsin. My mom is from a dairy farm family. I think maybe I’m not interested in the pastoral, but I also feel like pastoral doesn’t just mean the field. [Lake] Monona is in my poems over and over and over. When I moved to Atlanta and there was no water, I was just like, “Oh, what am I going to write about?”

Tone Madison: There are many ways in which this book is all-American—references to football, to presidents, to Civil War figures, to the everyday violences of being Black in America. What are your thoughts on what it means to be an American poet at this particular political moment?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: That’s so funny, because I was literally just on the book tour in England and Europe and they were like, “American poet Sasha Debevec-McKenney.” I’m okay with being called an American poet. Going back to the thing that I was saying of feeling like the book is a museum of my 20s, I think you can read it and be like, “This is a representation of a woman who lives in America in the 2010s.” I think we read so many books of poems by tenured poetry professors who are famous or who are rich, and that’s not that interesting. All the books I read in grad school were like, Trump books, of [those writers] being like, “Trump is bad, and America is bad. I’m just finding this out now.”

If I’m gonna call myself a wannabe historian, or if I’m gonna write about the things that I’m gonna write about, people can say, “She’s a political poet. She’s an American poet.” I think I hesitate to believe that poetry can be activism. I think a lot of poets want to believe that we’re activists, but who’s your audience? Whose minds are you changing? I write about what I like, and sometimes it happens to be about American politics or American history, but I don’t think I’m doing something radical or important. I do feel like I like writing about America, and I think I’ll always write about America, and I think I’ll always be interested in what it means to be an American. Because I don’t really know the answer to that question, and I don’t think that I ever will.

Tone Madison: To end on a fun note, which of the poems in this book, if any, do you think could be a Taylor Swift song?

Sasha Debevec-McKenney: Great question. First off, I feel like I’m not as revealing as her. That’s actually something I really love about her. Like I said, It’s really hard for me to access my emotions sometimes, or I get embarrassed, or I don’t want to be genuine. Like, I have to put a joke in there. I have to put a fact in there to balance out the real thoughts and feelings. I definitely think there’s one poem and the end is like, “This is our room. I made it for us.” And I’m always like… “Is that Our Song?”

There’s the love poem in the book, which I almost never read out loud. It’s called “Johnny Teaches Me How To Use a Power Drill In Reverse.” I think that’s the most Taylor Swift one, because that’s the only one where I’m legitimately like, “I like you so much.” And there’s some jokes, but they’re at my expense.

Sasha Debevec-McKenney will be in conversation with Chessy Normille on Friday, October 24, at 9 p.m. in the Central Library‘s third floor community rooms 301 and 302 as part of the Wisconsin Book Festival. Free, pre-signed copies of Joy Is My Middle Name will be distributed to all attendees on a first-come, first-served basis.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.