QueerCrip Pride from home

What disability can teach us about queer culture, care, and pride.

What disability can teach us about queer culture, care, and pride.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

It’s that time of summer again when my social media feed is filled with invites to local Pride events. The Big Gay PRIDE Market, Outreach LGBTQ+ Community Center’s Juneteenth Pride event, and the upcoming Madison Queer Liberation March on June 28 at James Madison Park.

I don’t even click that I’m interested. Unlike last summer, when I hoped I could summon some unusual energy to make my chronically ill body leave my home, this summer I’m homebound and in a wheelchair full-time. I am—or at least it feels like it—a bad queer.

I don’t have the energy to put on clothes most days beyond the T-shirt and stretchy pants that I also wear to sleep, much less to dress in seemingly iconic queer fashion—fishnets or Doc Martens. Hell, I don’t even put on shoes unless you count the carbon-fiber leg brace I slip into my chunky sneakers on the rare occasions I leave my home to visit the doctor.

As for hair, I can’t go to the salon to get the purple highlights I’ve wanted. I’m watching a Brad Mondo tutorial in my bathroom and hoping he won’t be ashamed of me as my tired arms hack off three inches. The uneven mess of wavy brown hair is hardly the queer haircut of my dreams.

The good news, however, is that the people who do see me—other queer disabled people—don’t seem to care. They accept me as I am, in pajamas, not having showered for over a week, sometimes in the hospital, and always too exhausted to leave my apartment.

Pride is often conflated to being “out” and unashamed of our sexual and gender identities. But what does being “out” mean when disability and chronic illness—things that disproportionately affect the LGBTQ+ community—keep queer people like me confined within our own homes or institutions?

If I can’t be witnessed, does that make my apartment one big closet? Or is the broader Pride movement—like most things that have transformed from their origins under capitalism—often inattentive to disabled people? Or is my big-ass closet also the site of radical acts of pride? After all, my queer chosen family keeps me alive through invisiblized care, and this, undoubtedly, is a form of love.

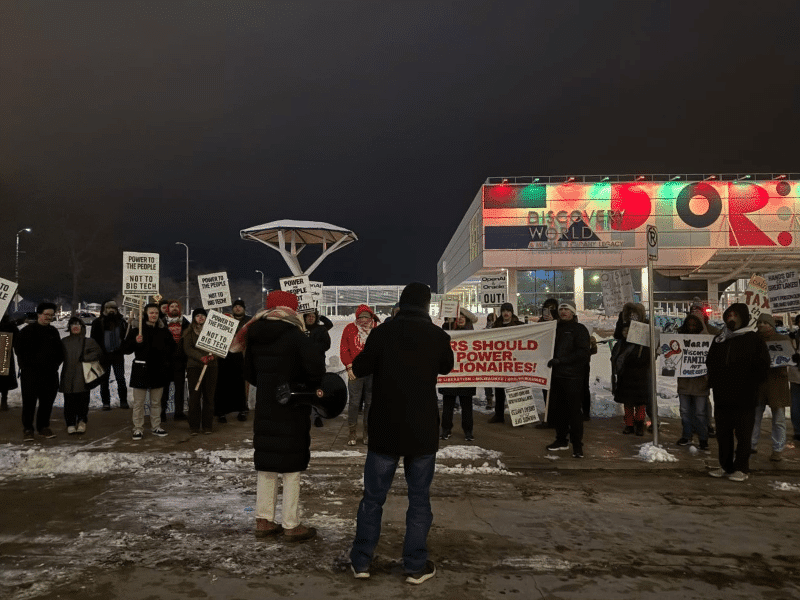

Before I became homebound, I never felt entirely welcome in public queer spaces that weren’t also explicitly disabled ones. Outreach’s Magic Pride Festival at Warner Park was always impossible for me to attend with the long bus route in the dead heat of summer. And COVID-19 only accentuated these divides between me and the queer community when many of my queer friends were quick to abandon wearing masks once the government dropped the mandate, unless they were disabled too. This pushed immunocompromised disabled people like me even further out of queer spaces. We quite literally could not risk our lives to be in the community. The abandoned solidarity from other progressive folks also normalized a political climate where the people still wearing masks have almost explicitly been people of color and disabled people. This opened us up to further social ostracization and harassment.

I shouldn’t have to remind queer folks that current and proposed legislation criminalizing mask-wearing, cuts to Medicaid, and rescinded disability civil rights guidance are just as violent to the LGBTQ+ community as bans against gender-affirming healthcare, and executive orders refusing to recognize any gender marker besides “male” or “female.” All of these things push queer, trans, and gender-diverse folks further into precarity, and closer to danger and death. Yet, too often, the former issues are siloed away from queer activism as “disability issues.”

In mid-June, a queer friend came to visit me from Minneapolis to keep me company on her way to a summer camp job in Michigan. In April, another queer friend sat with me in the emergency room and rolled me back through dark streets to my apartment at two in the morning. And yet another brought me food from the farmers’ market I can no longer attend.

What chronic illness and disability have taught me about Pride is that sometimes the most radical acts are those that may not even be publicly witnessed, but ensure our collective survival.

Like the protective power of normalization that comes with collective mask wearing, being “out” is important when queer existence becomes more criminalized. At the same time, especially during a time where being “out” comes with great risk, kinship that happens behind closed doors should not be underestimated nor minimized as a less powerful form of resistance and self-expression. Yes, even if it happens in the metaphorical closet.

In that regard, Pride doesn’t have to look like parades, festivals, or iconic fashion. It’s also mask blocs, sharing contact information for a local queer moving and handyman company for your housing insecure friend, fundraising to pay for unexpected medical expenses (thanks, terrible health insurance), grocery and medication pickups, and help with apartment cleanouts and drywall repair so as not to piss off your Trump-supporting landlord.

My queer community has helped me with all these things in the past year since I became profoundly ill. It is the queer disabled community who has taught me that caregiving, mutual aid, and the practice of giving a shit about each other are powerful legacies of queer culture. These things represent the kind of queer culture where I feel most welcome and at home. Best of all, they don’t require me to leave my home to be a part of it.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.