Protests, access, and the official story

Please stop bellyaching about encampments having media-trained spokespeople.

Please stop bellyaching about encampments having media-trained spokespeople.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

“Friends, please come say hello and tell me what you think.”

That phrase has been ricocheting around inside my skull for the past few days. If we are to believe Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan, that was how she greeted a group of pro-Palestine protestors at Columbia University last week. In the resulting column, published May 2, the closest Noonan comes to doing any reporting or research is to fail to get an interview with these young people:

I was on a bench taking notes as a group of young women, all in sunglasses, masks, and kaffiyehs [sic], walked by. “Friends, please come say hello and tell me what you think,” I called. [Editor’s note: Nobody talks like this unless they are a character in a 1940s screwball comedy, preferably putting on a Transatlantic accent and mixing up their fifth Harvey Wallbanger of the night.] They marched past, not making eye contact, save one, a beautiful girl of about 20. “I’m not trained,” she said. Which is what they’re instructed to say to corporate-media representatives who will twist your words. “I’m barely trained, you’re safe,” I called, and she laughed and half-halted. But her friends gave her a look and she conformed.

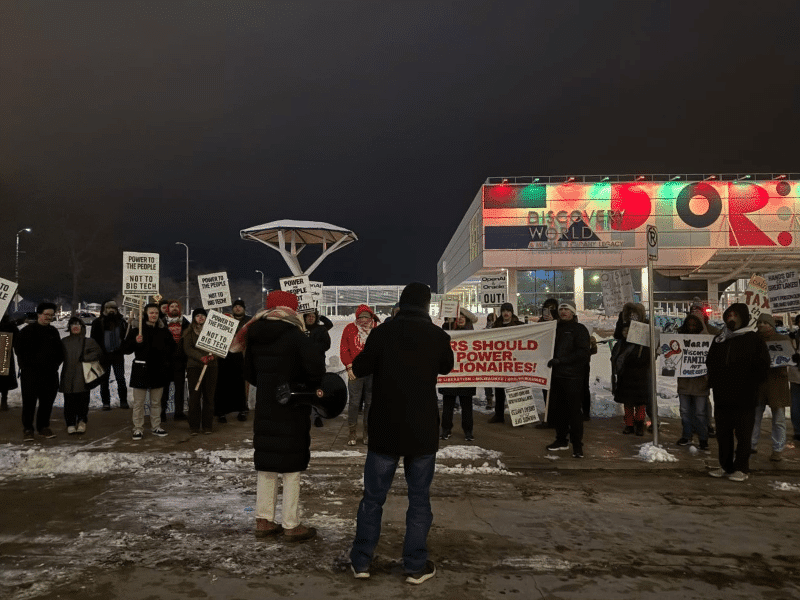

As student protestors on campuses across the country call for an end to Israel’s genocide in Gaza and demand that universities break institutional ties with Israel, many organizers have designated point people for talking with media. Protest organizers at UW-Madison’s Library Mall encampment have done the same, asking protestors not to speak with reporters unless they are “media-trained.”

This has upset an assortment of legacy media crusties and influencer dipshits. People like Noonan would have us believe that the practice is shocking and somehow coercive, evidence of how entitled, insular, ideologically rigid, intolerant, and Bad At Discourse today’s leftists and college students are. This narrative paints protestors as victims of group-think even as they show astonishing courage and conviction in opposing the genocide of Palestinians. While Noonan was failing journalism 101 in the field, student journalists covering the protests put everyone else in American media to shame. Reporters at Columbia’s student newspaper, Columbia Spectator, and its student-run radio station, WKCR, kept up their heroic efforts under nearly impossible, siege-like conditions. They gathered dozens of on-the-ground interviews and navigated all sorts of barriers to access as university officials locked down the campus and riot cops flooded in. As protestors trampled upon Noonan’s journalistic rights with their sinister keffiyehs and masks, the Israeli government kept slaughtering journalists on the ground in Gaza and kept up its effort to shut down Al Jazeera’s operations in the country.

It’s hard to blame protestors for wanting to control the narrative, since national media has a poor track record of conveying the messages of left-wing uprisings, from the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s to the Black Panthers to Occupy Wall Street. The impulse behind all this is pretty simple: protests aim to get across specific messages, among other goals. The encampments represent coordinated, deliberate efforts in which like-minded people push for a shared outcome. It takes a great deal of discipline to push hard against the status quo while enduring police attacks and counter-protests. A protest is not just a chaotic agglomeration of individuals who all showed up spontaneously at the same place one day, but it’s not an institution, either. It has to be just organized and strategic enough to make institutions listen. So, organizers have to decide what their message is, and create a strategy for getting that message across as consistently as they can.

Here at UW-Madison, police and UW System president Jay Rothman have flat-out lied about protestors’ behavior, claiming that protestors instigated the violence in last week’s police crackdown. Rothman has dismissed calls for divestment as a “red herring.” UW-Madison Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin continues to insist that all of this comes down to a technicality about tents. The encampment’s organizers have had to deflect blame for the alarming behavior of people not affiliated with the protest. Critics of the protests are determined to tar them as anti-Semitic, despite the fact many Jewish students are involved, and despite the fact that protestors have incorporated events like a “Liberation Shabbat” into the overwhelmingly peaceful, inclusive proceedings. Amid all the volatility and complexity and distortion and Michael Rapaport being a big whiny baby and every other damn thing, it makes sense to try to stay on-message.

Moreover, all the other institutions involved in this have spokespeople or a whole PR apparatus at their backs. Cops, campus administrators, elected officials, think tanks, lobbyists, and right-wing hate factories like Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty—literally every institution does this, often on a much more complicated scale and with far less honesty. Companies, government agencies, non-profits, and so forth pretty much always have spokespeople who take the lead on handling media inquiries. They might have job titles like Public Information Officer (PIO)—especially if they work for a police or fire department—or Director of Communications or External Relations Manager. Some of these people are good at their jobs and are genuinely helpful. Some of them are good at their jobs and incredibly obstructionist. Some will actually help you set up interviews with knowledgeable people at their organizations. Just as often, the spokesperson is the only person at a given institution who is allowed to talk to the press without authorization.

In any case, a great deal of the statements and factual claims we read in the news are mediated through “media-trained” people in one way or another. News outlets routinely publish crime stories that rely entirely upon the claims of a police PIO. Lots of humdrum workaday news stories cite press releases about business openings or arts events or non-profit initiatives or university research breakthroughs. Spokespeople for the White House and Pentagon play a huge role in shaping the news cycle, and rub elbows with reporters at grotesque affairs like the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. The corporations that own major media outlets like The Wall Street Journal have PR teams of their own.

Marketing and PR have dominated the public discourse for a long time. Journalists and just about everyone else have gotten used to it. Sure, any self-respecting journalist works hard to develop other sources. No one becomes a reporter just to pass along the authorized, official, canned story. Most people in the news business regard iron-fisted flaks as an annoying fact of life. We’ve all known the frustration of trying to work other sources at a given company or government department with the express goal of not ending up talking with the control-freak PR master, only to have our inquiries passed back to that very person.

Worse, these folks gain more power as the news industry becomes more depleted. Journalists have fewer resources to devote to investigative reporting, less time to cultivate sources, fewer opportunities to soak up institutional knowledge from veteran reporters and editors who’ve spent decades covering the same communities and beats. Most of us have never really had anything close to the resources and time we’d need to do our jobs the way we’d like to. Oh, and a lot of people quit journalism for better-paying, less-stressful PR jobs. This only compounds the frustration of dealing with the barriers that corporate and government spokespeople create. Let’s add another layer of friction to the situation: This work requires a lot of interpersonal finesse, but the field attracts tons of introverted, high-strung, awkward, self-righteous misfits. (Ask me how I know!) The feeling that we’re dying and they’re winning—it’s bound to boil over at times.

But rarely do I see journalists try to condemn someone for merely having a spokesperson or a media strategy. If anything, American media goes too easy on police PIOs and other government spokespeople—who, unlike most random people on the street, do owe the press and public answers. The people who fault protestors for having disciplined media strategy are often the same people who ask smarmy, obtuse questions about why people are protesting and refuse to listen to their answers.

If you understand all this context, then you understand that the outrage over protestors’ media strategy is selective bullshit. Before she sat on a bench at Columbia and tried to start an interview in truly bizarre fashion, Noonan wrote speeches for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. She is emblematic of the American media elite, even if she can’t report or write her way out of a wet paper bag these days (actually that makes her even more emblematic!). When Noonan hints darkly that a protestor “conformed” by not speaking with her, it’s not because the concept of shaping and safeguarding a narrative shocks her.

What bugs Noonan and certain other media folks, I think, is the sheer presumption of politically radical young people helping themselves to the same prerogatives that large institutions routinely employ when dealing with the press. How dare you!? Those PR strategies are not for you. Your betters at police departments and Fortune 500 companies have the right to set boundaries with media, but you must be a naive open book.

I also don’t think reporters should rely entirely on the statements of designated protest spokespeople. No one is forcing them to. Some of my colleagues at Tone Madison have interviewed spokespeople at the Library Mall encampment. They can provide helpful information and context, but like any spokespeople worth their salt, they are so on-message that it’s a little tough to get them off-script and into a deeper conversation. That’s just how it goes sometimes. You learn what you can from them, you learn what you can from other sources, you try to make sense of all of this in context.

All throughout her own piece, Noonan demonstrates that the protestors at Columbia were right not to trust her. This column makes lots of unsupported claims about protestors’ goals and motivations. She writes that protestors wear masks “to make observers feel menaced” and that “they don’t want allies.” She complains that protestors didn’t make eye contact. At best, Noonan is making guesses based on how the protestors’ strident tactics strike her. She notes that she visited Columbia “hours before” an ungodly number of cops raided the campus, but doesn’t acknowledge how the ongoing threat of police action might have put protestors on edge.

The protests, of course, also provide the world’s laziest commentators with ample confirmation of their panicked narratives about the collapse of free speech and open debate on campuses. Noonan states that some Columbia students “had mixed or unsure feelings about Israel and were trying to think it through. The demonstrators weren’t.” It does not occur to her that the demonstrators have thought things through, then arrived at the point where they made up their minds about the issue and took action. Indeed, if you’re a grifting campus-free-speech scold like Noonan or Caitlin Flanagan or John “terrified of a guy with a drum” McWhorter, this is the one thing you do not want college students (or really anyone younger than you or to your left, or just different from you) to do. No, true free speech is when college students plod meekly, endlessly, on a treadmill of argument and counter-argument. This infinite pageantry of discourse is so sacred, in fact, that any students who arrive at an actual conclusion about what they think must go immediately to jail. Again: Firm convictions, vehement expression, and bold action are not for you.

None of this is really about whether or not reporters are allowed to talk to non-media-trained sources at a protest. In the same way, the explosive debate over protest photography is not really about whether photojournalists are allowed to take photos of people in a public place. Of course you’re allowed to. Reporters around the country have successfully talked with and photographed all sorts of protestors these past few weeks, some media-trained and some not. All of this is about trust and rapport. It’s about which people we respect enough to treat as worthy of building trust and rapport. It’s about whose interests we consider when weighing the potential harm our work might cause.

The people journalists interview or photograph constantly have questions or concerns about what we’re doing, or conditions they’d like to set. That’s true for PR-savvy billionaires. It’s true for all manner of ordinary people who distrust the press for one reason or another. More often, people are talking with a reporter for the first time and don’t quite know what to expect. Sometimes their requests are reasonable and sometimes not. It’s all part of a continuous push-pull of negotiation and access.

In most cases, a journalist is not entitled to someone’s time or thoughts. When you run into an obstacle, you can throw a fit over how unfair it is to impede your work. You can take your ball and go home. But if you do this every time someone gives you the brush-off, you won’t get very far. (Generally speaking, most journalists are expected to base their stories on something meatier than “I tried to talk to someone and they wouldn’t talk to me and now I am reading all kinds of baseless nonsense into it.” That kind of thing only works in the hothouse of legacy media columnist types.) The work demands that you muster some finesse and empathy and patience and, of course, persistence.

Usually there’s a way to make someone comfortable talking with you and maintain your professional standards. For instance, sources often ask me to let them look at a draft of a story before I publish it. Like the vast majority of journalists, I consider this inappropriate, for all sorts of good reasons. I could count on one hand the exceptions I’ve made to that rule, in extremely delicate and specific cases. My standard answer is, “No, but if there is anything specific you have concerns or questions about, we can talk about that.” Usually that’s enough.

Most people just want to be respected and heard. If you can’t grasp that, you don’t deserve to look these brave young people in the eye.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.