“Milk Punch” revels in a Madison beautifully adrift

Erik Gunneson’s locally shot 2000 feature returns to the Wisconsin Film Festival in a new digital restoration for its 25th anniversary on April 5.

Erik Gunneson’s locally shot 2000 feature returns to the Wisconsin Film Festival in a new digital restoration for its 25th anniversary on April 5.

Though it centers around a joyride in a stolen car, Erik Gunneson’s 2000 film Milk Punch sets a relaxed pace. That allows all manner of little things to come to the fore—comic setpieces, sweet moments of friendship, familiar bygone places, impeccable music choices, and a whole collection of misfit objects that seem expertly (yet effortlessly) culled from thrift stores and yard sales. Even when something of a chase picks up speed, the characters are still drifting through life at the speed of 1990s Madison.

Gunneson has prepared a new 4K-resolution scan for the film’s 25th anniversary. It will screen during the 2025 Wisconsin Film Festival, on Saturday, April 5, at 6:45 p.m. at UW-Madison’s Music Hall. That screening quickly sold out of advance tickets, though attendees can try their luck on getting a “rush” ticket (i.e., line up before the screening and hope to get a last-minute ticket the fest has held back or one that will be freed up by a no-show). Gunneson is also planning an encore screening at the Bartell Theatre on Friday, April 11, at 7 p.m. An instructor in UW-Madison’s Department of Communication Arts, Gunneson screened the remastered Milk Punch for Tone Madison recently in an editing bay in Vilas Hall.

Shot on 16mm all over the Madison area (and a few points further out, including a skatepark in Rockford and a malt shop in Wautoma) between 1995 and 1997 with a largely amateur cast, Milk Punch has simply nothing to do with any of the clichés you’ve ever heard about our city. A now-defunct promotional website Gunneson set up for the film in 2000 defiantly noted that Milk Punch “contains no shots of the State Capitol or the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the two things that Hollywood most often comes to Madison to shoot.” Gunneson recalls that the website also contained deliberately misleading explanations for the film’s title—and even today, he still considers the actual explanation something of a spoiler. Suffice it to say that the payoff is worth it.

While Gunneson wrote and directed the film for his feature-length debut, he emphatically labels it a collaborative effort, right from the opening credits onward. It’s a fictional story enmeshed in a real community. When you’ve got this level of intimacy and familiarity with a place, you don’t need to lean on shots of the Capitol. You don’t need to idealize or exaggerate.

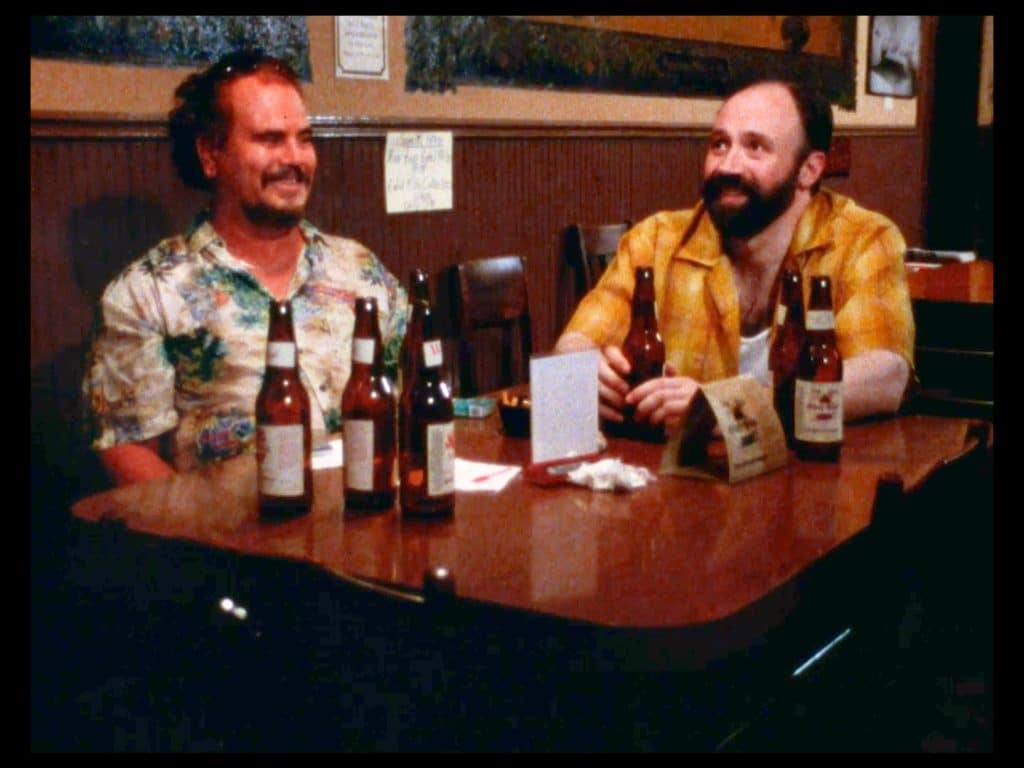

The plot centers around Boot (John Sarris) and Curly (Kris Hansen), two friends whiling away their 20s at nothing particularly ambitious—working at a record store, fishing, going to punk shows. Boot talks Curly into stealing a 1972 Oldsmobile Delta 88 from a convenience-store parking lot. The car’s middle-aged suburbanite owner, Buddy (Martin Schmidt), reacts in a brief flash of anger, then settles into handling the situation with a sort of good-humored disbelief. Buddy and his wannabe private detective brother Karl (Kevin Croak) cruise all over town looking for the Delta 88, a car they both cherish because it belonged to their late father. Meanwhile, Boot and Curly pick up their friend Verona (Liz Avery) and embark on a crime spree that consists of nothing particularly ambitious—buying silly outfits on Buddy’s dime (err, credit card), drinking beer, having a little fashion show with their ill-gotten loot.

Much as it’d be fair to call this a Gen-X document, Milk Punch‘s appeal doesn’t depend on the nostalgia of any particular generation of Madisonians, even 25 years out. Some of the characters make oh-so-Gen-X wisecracks about the evils of digital things, but the digital restoration sacrifices none of the film’s frizzy analog richness. Fondness becomes frankness. Boredom becomes inviting. Anticlimax becomes a narrative strength.

No place does anticlimax like Madison, after all, and Gunneson clearly grasped that when he made this film. He shows us a Madison that’s a bit more brash than the Madison of today, but also warmer and more richly textured, less hectic. A Madison with more of a working-class chip on its shoulder. (At one point, Boot disdainfully calls Curly a “college boy,” because Curly went for a few semesters and dropped out.) Watching Milk Punch, one can actually, shockingly, imagine Madison being a cheap and fun place to live. Avery’s sly, funny performance as Verona evokes a sort of person who tends to be drawn to Madison in any era—people who can make aimlessness seem inspired and alluring, and who at some point end up working in a call center.

In this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival guide, Artistic Director Mike King correctly writes that “it’s time for someone to press the [Milk Punch] soundtrack on vinyl.” Gunneson’s music choices for Milk Punch also transcend the standard-issue narratives you might have heard about music in Madison in the ’90s. Viewers will of course hear Killdozer and other rusty-bladed noise and punk bands of the era, but country music plays an even more prominent role here, and other selections hit on reggae, salsa, and swanky lounge jazz. Shellac’s “Wingwalker” shows up in its original form, and in a country-style cover credited to the Landine Brothers—a testament to Gunneson’s knack for reaching fluidly across different cultural referents.

Gunneson and editor Gretta Wing Miller (another longtime Madison-based filmmaker) unfold the story in a deliberate, non-linear structure, carefully keeping it medium-paced. Masterfully, if paradoxically, they end up creating a symphony of grace notes. Milk Punch has a structure. Above all, that structure encourages viewers to revel in brief moments and fine details. A malt shop’s neon sign reflected in the polished black hood of the Delta 88. (Gaze just-so at the mundane and sometimes it will dazzle you, Gunneson and a devoted cinematographer team of Eric J. Nelson, Team Bashet, and Michael Bober seem to be telling us.) A short but crisply executed shot from the inside of a moving Madison Metro bus. Buddy’s sweetly smart-assed banter with his wife Jane (Roberta Levine). The subtle class divide between Buddy and the tacky, acquisitive Karl. A novelty lighter, shaped like a cowboy boot, perched on the dash of the stolen car. An interior shot of Le Tigre Lounge, looking then almost exactly as it does today. Show flyers for Xerobot and other brilliantly warped Madison bands of the past. Boot stealing live bait to catch fish that have yet to get marinated in PFAS, namely a prized muskie he names “Don Cornelius.”

And of course, Milk Punch offers dozens, maybe hundreds, of spot-that-place/person/thing opportunities for a Madison audience, both on-screen and in the credits. I’ve been watching Hansen play in Madison bands (including National Beekeepers Society, El Valiente, and Building On Buildings) practically since I got to town in 2006. So just seeing him portray a younger, more sullen character was quite a revelation. And then, well, I won’t spoil the whole litany of places in the film that have changed a lot, changed very little, or burned down.

Gunneson’s playful, enduring film allows viewers plenty of time to sink into a time and a place, to understand it in a way that can never be rushed.

Correction (3/28/2025): The initially published version of this article misspelled John Sarris’ name. It has been updated with the correct spelling.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.