Who was this for?

Voters shouldn’t have to endure a barrage of useless, misfired election ads.

Voters shouldn’t have to endure a barrage of useless, misfired election ads.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

Somewhere deep in the bowels of the national Democratic Party’s contact list, my phone number (which I’ve had since 2020) is listed under the name “Steven.” More recently, I’ve also received messages for “Cristal,” who I assume is the most recent owner of my phone number because I occasionally get official-sounding phone calls looking for Cristal. Most recently, someone in the Democratic Party coalition found my real name, but those messages are not consistent. As I was combing through political texts for this story, I found that the same phone number sent a text addressed to “Christina,” and then the next day switched to “Cristal.”

But most of the messages from Democrats and their Political Action Committees have been for Steven. Based on the sheer bulk of messages, they must be really concerned with whether Steven is voting and for whom, and are convinced that maybe the next message will get Steven to sign a pact, fill out a survey, or send $5 or $10.

And I’m sure this isn’t a solely Democratic problem. Probably due to the Dane County area code, Republicans have decided I’m not their target audience, but I’m sure people in “red” parts of the state are just as inundated as we are. (Although I somehow got onto a “Moms for Liberty” list, which has been… illuminating.) For me, the messages I’ve received for Steven are an encapsulation of the problems of our politics today—political parties feel entitled to our time, attention, and money, and they don’t even know our names, much less what we want from our elected representatives.

It’s not like either party (or its constellation of aligned PACs) is short on the resources to get this right. The week before the election, almost $1 billion was spent on political advertising nationwide, with $23 million spent for Wisconsin and Michigan Senate races. That brought the total nationwide spending for the November 5 Presidential election to nearly $10 billion as of November 1. In Wisconsin, that total was estimated to be $673 million, a 300% increase from the $209 million spent in 2020. That’s a lot of money spent on texts we immediately delete and ads we immediately mute or skip.

It’s particularly galling at a time when many Americans are struggling to meet their basic needs in the face of rising housing costs. And in Wisconsin, where our Republican-controlled legislature is starving school districts and municipalities to the point that they hold regular referendums to pay for basic services, I bet everyone’s thinking there’s better uses for those resources. Bill Hogseth, an organizer with GrassRoots Organizing in Western Wisconsin (GROWW), wrote last year for the Wisconsin Examiner that the spring 2023 election, “which lasted only five weeks from the primary in late February to the general election in early April—cost more than $45 million, an amount that would fully fund my kid’s school district in Elk Mound, Wisconsin, for three-and-a-half years.”

Why does anyone think this is an effective way to mobilize the electorate? For a while it seemed like it was, though now the reality is more complicated. In an October article for the website The Conversation, Heather LaMarre, associate professor of media and communication at Temple University, writes that not only are political ads not effective tools for engaging voters, there’s evidence they can have the opposite impact.

“When voters perceive ads as unfair or manipulative, they are less likely to vote for the candidate or party producing the ads. And when subjected to repeated unwanted exposure to political ads, they can experience ‘psychological reactance‘ and behave opposite of what the ads intended,” writes LaMarre. “Some studies also suggest that negative ads create election stress, which can reduce voter turnout among the less politically interested.”

This is also yet another story of overconfident tech gone wrong. LaMarre writes that microtargeting—using data from social media to fine-tune messaging to voters—has unsurprisingly turned off voters. “Not only are these microtargeted messages manipulative, but they can be an unwelcome disruption and invasion of privacy, especially among the politically uninterested,” LaMarre writes.

While political ads, and even attack ads, have been a mainstay of American politics since the 1800s, we can’t talk about the current onslaught without bringing up the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. FEC, which essentially opened the floodgates of money into politics and ushered in our current era of campaign financing and spending. After the decision, Democrats positioned themselves as the party that wanted to get money out of politics—until the financial tide turned and the party found itself able to out-spend Republicans.

But that funding can come with some ugly strings attached. Expedia chairman Barry Diller and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, billionaires who donated the maximum allowed amount of $7 million to Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign, both told the press they would want a Harris administration to remove Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chair Lina Khan. Khan is the first FTC chair in a generation to actually use the power of the FTC for its intended purpose—as a check on corporate power. The question of how Harris would respond to such an unethical ask is moot, thanks to the election results. But our current lax campaign finance laws have emboldened billionaires to make such nakedly egregious deals with politicians, some of whom, including President-elect Donald Trump, could take them up on those offers.

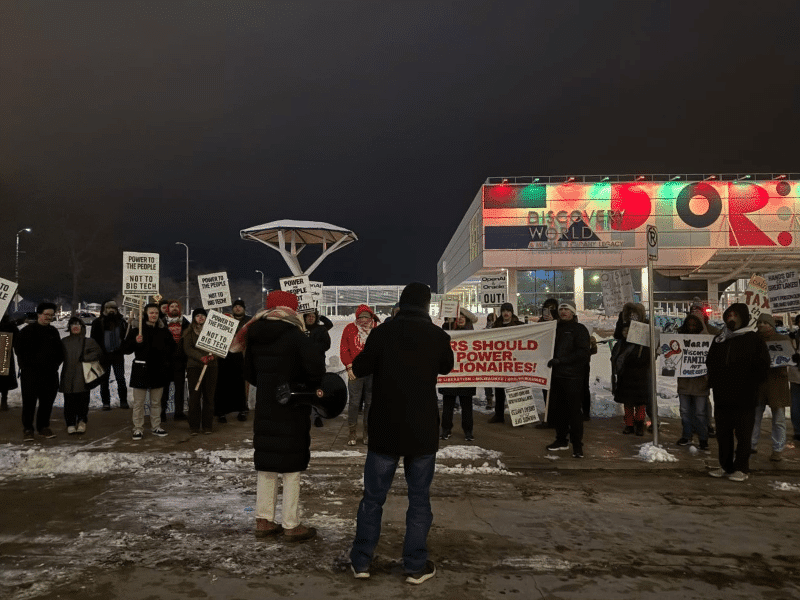

As much as everyone wants answers for Tuesday’s results, it’ll be months before we have a full picture of what happened and why. Regardless, I’m willing to bet the outsized campaign spending and advertising backfired—and/or that Republicans outplayed Democrats at that ugly brute-force game. Going forward, I would argue that instead of investing in invasive, nasty attack ads, it’s better for campaigns to invest in on-the-ground organizers, the people who day-in and day-out, are mobilizing their community. Holding in-person events and canvassing door-to-door is too quantitatively squishy for many researchers, making it hard to study the effectiveness of these approaches. But re-learning how to talk one-on-one about politics and engage in community events could help bring us back to a politics of finding common ground based in reality, instead of the deranged, inflammatory rhetoric we see from the right, designed to get our amygdalas firing on all cylinders.

The ever-growing presence of political ads—particularly attack ads—is misfiring and feeding the public’s growing disillusionment with politics. As tempting as a fat war chest is going into a campaign for candidates and parties, the best move forward is to clamp down on campaign financing and get money out of politics—for the sake of our collective sanity, and our flailing democracy.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.