“Message From Our Planet” captures humanity obsessed with studying and rediscovering itself

In an exhibit running through June 2 at the Chazen Museum of Art, technology provides us the opportunity for our productive failures to find new means of expression.

In an exhibit running through June 2 at the Chazen Museum of Art, technology provides us the opportunity for our productive failures to find new means of expression.

There’s a paradox central to any work of art about outer space, or humanity’s envisioned future; there’s bound to be something incomplete in only using our own tools to predict things we can’t know. The fascination with the unknown that artistically drives works like these is hampered by context; our speculative fictions are only as realized as our technology allows. Even when art focuses on other subjects, the industrial reality of artistic production means that each piece ends up a sort of instant artifact of its time.

This is an idea lurking throughout Message From Our Planet, a multi-artist exhibition that opened in February at the Chazen Museum of Art, which contains new media art from the Thoma Foundation collection. Running through Sunday, June 2, the exhibition is billed as a “time capsule sent from our common era,” but Message From Our Planet shows a present defined by the productive disconnect between society and its tools.

Christian Marclay, one of the few who could be considered a big name in video art, is the only artist with two pieces in the exhibit. His well-known Telephones (1995), a found-footage collage of phone calls throughout cinema history, is featured. Marclay’s other work here, Lids And Straws (2016), is also a catalog of its titular objects, with 60 images of littered straws and lids timed to the tick of a clock. Each image lasts for precisely a second before morphing into the next one.

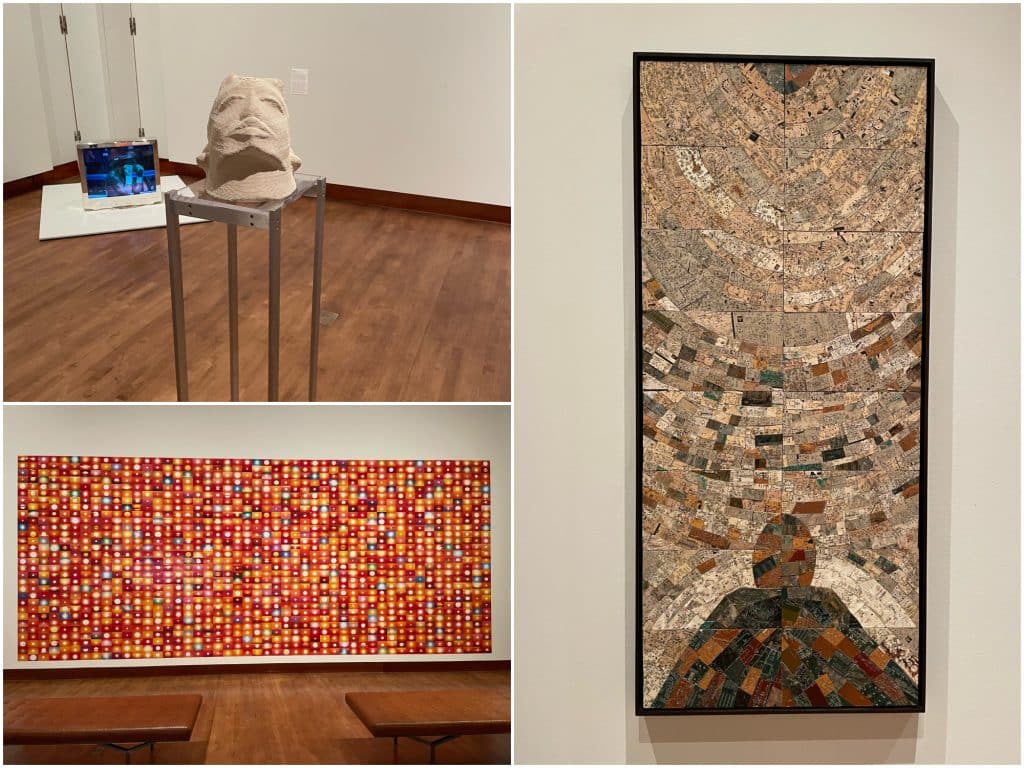

Cataloging is a consistent theme throughout the show, particularly in the handful of non-video pieces which are decidedly still “contemporary” in their use of recent technologies. Search engines make a few appearances, as they are used to collect the rainbow of Google image searches in Jason Salavon’s <Color> Wheel (2018) and the grid of dazzlingly ordinary sunsets in Penelope Umbrico’s aptly titled 48,586,054 Suns From Sunsets From Flickr (Partial) 11/05/20 (2020).

The works largely take different routes toward the same banality of human experience, verifying that people all, indeed, see the same sunsets and garbage. Elsewhere, technology is recycled and reborn as raw materials, like the 16mm film strips of Sabrina Gschwandtner’s Expanding/Receding Squares (2014) or the repurposed circuit boards collaged in Elias Sime’s TIGHTROPE: (1) While Observing… (2018).

Sculptor Matthew Angelo Harrison embodies the exhibit’s faux-ethnographic quality the best with his Braided Woman (2018), a 3D-printed ceramic mask crafted from an aggregate model of the Makonde tribe’s Lipiko “helmet” masks. While the source objects are historical, Harrison has created a new artifact tasked with plugging holes in the accessible archive. Some of the best video work in the exhibit also uses this creative/speculative approach, like Tabita Rezaire’s hilarious but pointed Sorry For Real (2015), in which the “Western World” leaves a 16-minute robotic voicemail on a floating iPhone to apologize for all systemic oppression.

Mohawk artist Skawennati similarly uses her chosen technology for alt-historical ends, animating her web series TimeTraveller™ (2007-2014, projected in its entirety in the exhibit) within the virtual world of Second Life, where Skawennati’s protagonist uses time-traveling glasses to see past injustices faced by Indigenous people but also to see alternative and optimistic futures. Does Skawennati really find Second Life and the imaginary time-travel tech to be useful or liberatory? Maybe, but maybe not. The point of imagining reality in the simplified polygons of a video game is a sort of resignation—an acceptance that our present tools, even as they change to make more convincing simulations, are still only that. Culture and history can only truly exist in the mind, which themselves are increasingly outsourced. Message From Our Planet shows a humanity obsessed with studying and rediscovering itself, and the ways technology provides us the opportunity for productive failures in finding new means of expression.

To coincide with the Chazen’s exhibit and its presentation as a sort of time capsule for another world, UW Cinematheque has programmed three disparate narrative films about contact with alien life on select Sundays this spring semester. The films, being shown on 35mm in the Chazen theater, run the gamut of genre and tone. The Spielbergian childhood fantasy of Joe Dante’s Explorers (1985) is on one end on the spectrum (screening on March 24 at 2 p.m.), with the arthouse impressionism of Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) on the other (screening on April 28 at 2 p.m.). John Carpenter’s relatively grounded Starman (1984), which screened in February, stands somewhere in the middle.

In each of the films, the aliens are a narrative pretext for the earthlings (or the audience) to understand themselves. This is perhaps least explicit in The Man Who Fell To Earth, where the alien Thomas Jerome Newton (David Bowie)’s adaptations largely happen offscreen. Newton hits the narrative running as a savvy capitalist, falling prey to other human addictions like alcohol and television as the film progresses.

The other two movies feature aliens as blank slates, only intelligible to the characters because of their ability to regurgitate human culture. This is extra dispiriting in the would-be dazzling climactic section of Explorers; the ultimate meeting between titular kid explorers (Ethan Hawke, River Phoenix, and Jason Presson) is deflated when the rapid pop-culture pastiche used by the aliens to communicate merely reveals the inanity and uselessness of the culture put forth by our world. For Ben (Hawke), his disappointment in the creatures is a disappointment in himself. He hates the mirror that reveals his fantasies as such. As with all these selected films, the alien is itself a sort of machine working algorithmically to reflect human values back at us. For Roeg and Dante, the aliens reveal our society’s capitalist greed and consumerism; but the Alien Mirror can be a sort of fantasy fulfillment, too, as it is in Starman. Looking at the human race from outside allows a writer to plug in any humanist observation they want, especially if it’s about our unique capacity for love.

In an age where our thoughts and actions are so thoroughly outsourced, artists can’t help but adopt a sort of transhumanism and collaborate with machines (or artificial intelligence) to understand the self through whatever data is fed back to us. In fiction, we launder this data through blank-slate constructs, which are similarly limited by the human imagination that created them. This feedback loop fossilizes art in its own time, and the fissures between technological and biological consciousnesses become ever more clear. For the imagined audiences looking back at us (and the real ones roaming the Chazen galleries), they’ll find a people still picking at the parameters of how we create.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.