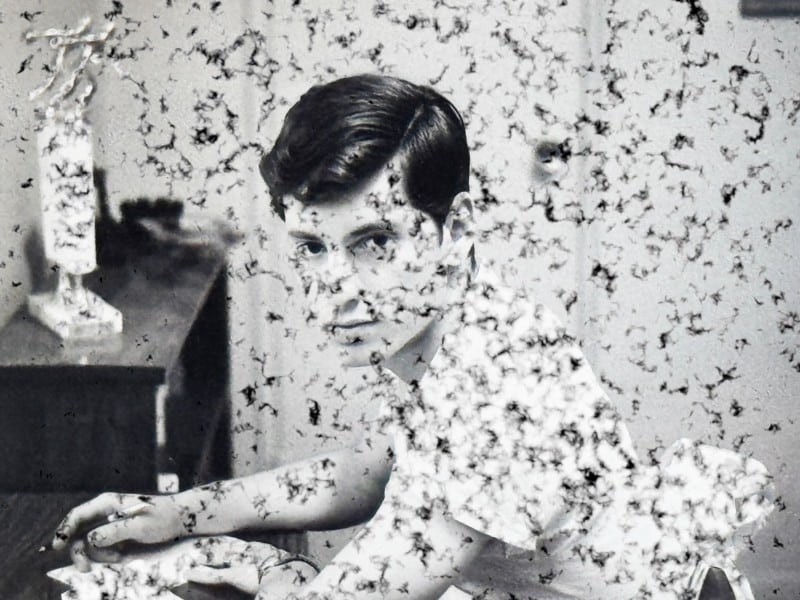

“Melomaniac” is a blurry but striking snapshot of an obsessive documentarian

Katlin Schneider’s roughshod ode to Chicago indie-rock show taper Aadam Jacobs screens at the Wisconsin Film Festival on April 6.

Katlin Schneider’s roughshod ode to Chicago indie-rock show taper Aadam Jacobs screens at the Wisconsin Film Festival on April 6.

For the past 18 years, I have dedicated hundreds of hours to recording shows. So when Katlin Schneider’s documentary about Aadam Jacobs—a Chicago show taper who became a prominent fixture of the city’s indie-rock scene in the ’80s and ’90s—was announced, I met the news with excitement and a host of questions. Would Schneider interrogate the act of recording shows? What drives an individual to commit themselves to taping? Would it become a project of meta-symbiosis: a documentarian documenting a documentarian? How forthcoming would Jacobs be as a subject? What level of clarity would he be able to offer on taping and himself?

After viewing Melomaniac (2023), which is screening as part of the 2024 Wisconsin Film Festival at UW Music Hall on Saturday, April 6, at 9 p.m. (tickets are still available as of the publication date), I’m not sure that most of those questions have clear-cut answers. Part of that ambiguity stems from Jacobs’ apparent uncertainty in his motives, which ranged from a sense of personal obligation, to a mindfulness of historical preservation, to a genuine confusion over what drove him to be extraordinarily persistent.

Jacobs offers a fair few “I don’t know” replies as he struggles for the right words before Schneider’s film lands on some clarity in its final stretch: “Why me? I don’t know. If it weren’t me, it never would have happened… If I don’t do it, it’s lost forever,” says Jacobs, expounding on why he committed to taping. “There is a responsibility to history. That stuff needs to be taken care of, regardless of whether I liked it or not.” Melomaniac takes time and caution in its efforts to unlock the conviction of those answers, making allowances for Jacobs’ more noncommittal contemplation in anticipation of the eventual payoff.

What becomes unavoidably clear over Melomaniac‘s 70 minutes is something that I have long held to be true: in the right hands, documenting shows is an act of love that is committed to the interests of archiving history and honoring the artistic contributions of those being recorded. Jacobs estimates he has exceeded 10,000 tapes worth of recordings that chronicle over 40,000 full sets. Most of them were recorded professionally, with a highly visible equipment footprint that was an occasional point of contention and concern. He became synonymous with Chicago’s live music scene during his extended run as a taper, leading former Schubas and Lincoln Hall booker Matt Rucins to compare his presence to Chicago native Thax Douglas (who in recent years has also made his mark on Madison’s music community) and the late Beatle Bob.

A range of personalities appear throughout the documentary to repeatedly support the claim of Jacobs’ ubiquity, with a few backpedaling on their at-the-time views of his show-taping efforts.

Of the assorted talking heads, the most notable is undoubtedly Trenchmouth drummer-turned-comedy darling Fred Armisen, who speaks glowingly of Jacobs throughout the film’s duration. The other members of Trenchmouth, along with members of Eleventh Dream Day, The Mekons, The Ms, Naked Raygun, and Antietam, offer additional insight on their experiences with Jacobs, as well as their experiences with the Chicago indie-rock scene writ large from the mid-’80s to early ’90s. Schneider enlists a shortlist of present and former venue owners and/or bookers from a series of notable Chicago clubs for commentary. The Metro, The Hideout, Schubas, and Lounge Ax are all represented with reverence throughout the film, which eventually ties into Melomaniac‘s most glaring flaw.

In Melomaniac‘s midsection, when Schneider examines the history of the bands, venues, and a specific era of Chicago music Jacobs was attached to, the ostensible subject of the documentary is almost entirely swept aside. This quarter of the film does a wonderful job of illustrating the environment Jacobs operated in, but he’s barely mentioned or quoted. There’s certainly enough worthwhile content to warrant another doc, but here it feels oddly disconnected. In its current context, it contributes little beyond fleshing out a specific time period with greater specificity and demonstrating a genuine interest in the bands and venues that snagged Jacobs’ favor.

But just when it feels like the film is on the verge of entirely derailing its momentum by distancing Jacobs from the narrative, Schneider swings Jacobs back into focus. Melomaniac‘s final 10 minutes drive into the heart of the film’s true engine, with a series of quietly profound observations on how recognizing impermanence is intrinsically connected to the importance of preserving history.

As the assembled chorus of Jacobs’ friends, collaborators, and contemporaries make painstakingly clear in Melomaniac‘s concluding moments, Jacobs’ work has become an essential archive. A devastating poignancy emerges in Melomaniac‘s finale, as the film’s participants tend to questions about their own mortality, the nature of legacy, and the fate of Jacobs’ many, many tapes. “That archive is not going to be any good if nobody listens to it. It’s going to be dead,” intones sketch artist Dmitry Samarov, with genuine gravity. Others touch on how meaningful it would be to have access to those tapes in their quest to more firmly reconnect with their memories of the time, seemingly cognizant of the fact that those memories may one day fade. That’s a powerful closer that pays appropriate respect to Jacobs’ tenacity and the true value of his work.

Melomaniac is a flawed documentary, in a lot of ways. And yet, most of its flaws feel emblematic of its core focus: being an ode to not Jacobs, but to live music documentation. Whether it’s the lens chips that are visible in spots throughout the film, camera focus issues, the white noise or occasionally abrupt audio cuts (though one such cut of Jacobs’ cat starting to trill comes across as enormously endearing), or engaging in curious narrative decisions, Melomaniac still manages to exude an earnest charm. Something about its roughshod construction and decidedly DIY nature—something that can be evidenced in the film’s now-completed fundraiser to secure musical licensing rights—feels inherently connected to the artistic work Jacobs devoted an important section of his life to documenting.

Imperfection is an essential aspect of art; and when it’s a defining feature, it can come across—as it does here—as exceedingly honest. In the quest to capture artistic history, Jacobs winds up with a story worth capturing in its own right. Schneider’s doc has done that story a fair bit of justice, with its most potent moments arriving by flipping the script and putting the recorder firmly in the spotlight.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.