Mandy Moe Pwint Tu tries to alchemize what she couldn’t witness

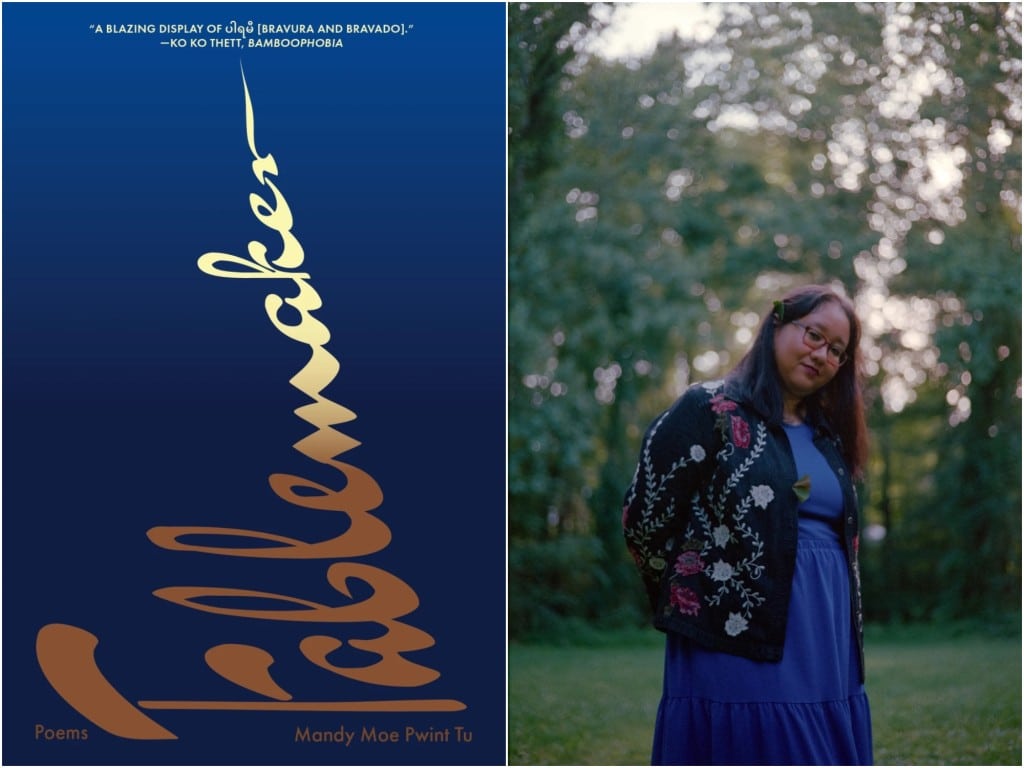

The Madison-based poet transfigures the anguish of grief into the catharsis of memory in debut collection, “Fablemaker.”

What can be cultivated in the space between memory and truth? To what do you anchor yourself when everything feels borrowed? What stories do we tell ourselves to simply survive?

These are questions at the heart of Fablemaker, the debut poetry collection of Madison-based Burmese writer Mandy Moe Pwint Tu, who is also the author of the chapbooks Monsoon Daughter, Unsprung, and the forthcoming Burma Girl. Tu recounts the overlapping, compounding griefs of her estranged father’s death, her home country’s military occupation, and her alienated existence in the United States as a visa holder and asylee. In this poetry collection, Tu positions herself as a masterful storyteller—or more accurately, a fablemaker—who weaves together Western fantasy, Burmese folktale, and personal narrative into a dizzying tale that brings us all over the world (Myanmar, Tennessee, Wisconsin, and landscapes only fit for daydreams) and presents us with one way to turn anguish into beauty.

What some might consider to be obsession is seen as faithful devotion in Fablemaker. Again and again, Tu revisits pivotal occasions for which she was not present, like the moments leading up to her father’s death (“My Father Died”) or the spring revolution in Myanmar following a military coup (“On Being Absent For The Revolution”). She repeatedly summons the same few images as if they were an incantation—a yellow door, a blue oxygen tank, a betel nut, pond water—touchstones that aim to legitimize Tu’s witness, to assert her here-ness. It does not matter exactly that she, as the narrator of these poems, was not physically there in those instances, so long as she can alchemize a new temporality in which she is.

Though they are saturated with grief, the poems within Fablemaker are not bogged down by their own sadness. Instead, they are buoyed by a yearning to forgive and the dream of a softer tomorrow. For example, rather than insisting on her father’s monstrosity (labeling him “beast, monster, ogre” or “spider, lizard, frog”), Tu instead concedes to a more empathetic understanding: “But mostly we called him Dad because the thing / that possessed him was only a sadder self.” And, throughout a series of poems all entitled “Dear Fellow Fablemaker,” which serves as the book’s backbone, Tu strikes the balance between confession and advice, leaving her readers with an eye toward the future after a full journey of looking back: “This is a story / I’ll tell someday […] Here where the world ends, / and I don’t end with it.”

In early August, a month ahead of the collection’s release with Gaudy Boy Press, I met up with Tu at Johnson Public House to discuss Fablemaker, the role that fables have played in her life, the functions and limitations of poetry, and writing in the face of political precarity.

Tone Madison: When and how did you first come to fables and fantasy?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: I came to fables before I came to fantasy. My father raised my brother and me on Aesop’s Fables, and they provided guidance on how to live our lives. In tandem with that, our mother told us Burmese folktales—they weren’t as explicit in their life lessons, but the general takeaway—especially for me as a girl—was, “Be an obedient child.” Many of the folktales I took to heart were predicated on the idea of, “If you’re an obedient person, if you’re an obedient girl, good things will happen to you.” So this was in the air as I grew up.

Then, in April 2007, I got into fantasy via The Lord Of The Rings. It was one of those stories that effectively blew my tiny 11-year-old mind: I didn’t know that something like that was possible, because it spanned, seemingly, every possible breadth of imagination: the scope of the land, the language, the peoples. I was like, “Oh, my God, someone can do this. I can just do this.”

At this point in time, I was going through a turbulent family life. By 2007, my parents had separated. My mother, brother, and I had just returned from India, and we were adjusting to life back in Yangon. I think I latched onto the fantastical as a form of escapism, which practically everyone in my life took issue with, because they couldn’t see the point. All they knew was that I was writing a lot, and I was writing fantastical stories. I was emulating Tolkien as much as I could. I was reading mostly fantasy novels. My teachers would be like, “Hey, this isn’t real life. You should be more engaged in the real world.”

But I was engaging with the real world; it was impossible not to. We were still under a military dictatorship. It was necessary for my well-being to have an escape. Fantasy offered me a sense of safety; it was a vehicle through which to access emotions that I didn’t feel safe enough to access or express in my day-to-day life. But this, of course, was impossible to articulate as a teenager. All I knew was that fantasy was expanding my sense of the world, especially at a time when everything else seemed to restrict it.

Tone Madison: I noticed that in some of the epigraphs, you chose feature poets who are dear to you and friends of yours. To me, this speaks to this idea of curating your own lineage in the face of its deliberate severance. Could you talk a little bit about who your biggest literary influences were in writing this book?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: There were more than a handful of influences. I think Sean [Bishop]’s book, The Night We’re Not Sleeping In, was very instrumental. I basically stole a version of this series of poems [that he has] called “Secret Fellow Sufferers.” I was reading his book a lot in the past year as I was moving through my own grief. His book deals with his father’s death, too, so every time I was feeling grief about my own father and felt that my work was too close to those feelings, I would read The Night We’re Not Sleeping In as a balm to that grief, so it kind of seeped into the work I was writing. Of course, there’s Whereas by Layli Long Soldier that taught me how to write about the political, about resistance. Noor Hindi’s Dear God, Dear Bones, Dear Yellow… I feel like a good number of the poems that are bigger and take up more space are thanks to Noor Hindi. Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam is also amazing.

Tone Madison: In a previous interview of ours about Monsoon Daughter, you said that the chapbook wouldn’t exist at all had it not been for your father’s death in 2021. I thought about that a lot when reading the poem “I Was Always A Poet With A Dead Father.” What do you seek to accomplish in writing for and about him?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: There was a strange thing that happened when Fablemaker was picked up. After the night [that I found out I won], after a very public acceptance, I got really sad. And I was like “Why am I sad? Why can’t I have a normal reaction? Why can’t this be a happy thing?” So I was sort of sitting with that the next day, and I was asking myself, “Why am I consumed by sadness for this really great thing that I’ve been working towards for multiple years at this point?” I realized that I ask way too much of my poetry. The irrational part of my brain thought, “If Fablemaker got picked up, if I was granted that miracle, then it would undo the past four years.” It would bring my father back, which is the ultimate fable. It was an insane thought, but this is what I was hoping this book would do, which is irrational and impossible, right?

But it’s been cool to continue working on this book, because it moved from an earlier draft to Fablemaker and it became more expansive in terms of it now being about my family and not just about my father. There are more poems about my mother. There are poems about my brother. It’s become a family testimony that the initial draft of the book couldn’t think to do. One of the poems, “Decisions,” was nearly not in the book because it was a last-minute addition where I [realized], “Okay, this is the arc.” But as the book has moved towards publication, I feel my father a little bit more. One of the songs that he loved was “A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes” from Disney’s Cinderella (1950). And on the day I posted my cover reveal, the song was playing in my head, and I was like, “Where is this coming from? I haven’t thought about this song in years.” And I was like, “Oh, he’s here.” It’s kind of brought him back to me in a way, but obviously not in the way that I initially thought. It’s been very healing. I think now I’m like, “Okay, on some level, I’m done grieving him.” Although of course, it’s never done, but I think we’ve moved on to a different stage of it.

Tone Madison: There are many times in these poems where you contemplate the consequence of elegy (“This life I have spent running from my father. / I don’t ask how much I’ve ruined with this looking back.”)—of remembering your dead. What is your perspective on it now? Do you think it’ll change once the book is out in the world?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: When it comes to my father and all my loved ones in Myanmar now, my relationship with elegy is fraught because I’m not there. In part, a lot of the poems [in Fablemaker] I wrote because when my father died. It was mid-pandemic and no one was going anywhere. It was also mid-revolution; I was in the U.S., and he was in Burma, and I received fragments of the story of how he died. My mother, my relatives, told me, “It was because of this, it was because of that. We got him an oxygen tank, and at some point he seemed fine, and then he wasn’t.”

I haven’t spoken to his wife who was with him when he died, so I haven’t even gotten that part of the story. There were no funerals because of the pandemic, and one of our relatives took his body to the crematorium on the outskirts of town. This is where fablemaking becomes really necessary in my elegiac process, because I can’t process something I don’t know. A lot of this grief began in a very disembodied way, and as I began to fill in the gaps, I started to feel it more in my body. I had to take the things that people had told me and imagine what it must have been like for him at that point of death, and retroactively insert presence into what is a very clear absence. I haven’t gone home since I first got to the U.S., so it’s been years at this point. In part, the elegies in this book are, on some level, just me trying to make stuff up to allow myself to process what I need to, to get through the pain. So the stories shift. And I imagine they’ll continue shifting as I go on living. I think it’s a core part of this book: this sort of grasping, then letting go.

Tone Madison: A number of your poems feature lines from government officials and statements. Can you talk a little bit about that research process, and how you engage with docu-poetics?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: This is all the Unsprung work. It was 2022, and I’d been writing poems about the revolution since the coup happened. I went on Twitter and the UN had put out another statement in which they were “deeply concerned.” And I was like, “Are we deeply concerned again? Could we stop being deeply concerned and could we do something about it?”

I think with the coup and with the revolution… the illusion shattered: If we were going to get help, we would have gotten help at that point. We were never going to get help because they were going to keep putting out stupid statements. So I wrote a sestina, and I was like, “I’m going to do more of this because I have a lot more rage. I was pulling documents from the United Nations website, I was doing erasures… One of my favorite poems in Fablemaker is the “Dear Fellow Fablemaker” poem that incorporates language from Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, which was drafted by the military. It felt very rife with rage, with power. The 2008 Constitution wasn’t something I had ever really read. I knew what was in it, but pulling language from the document itself helped me scaffold my own experiences amid a larger structural context.

I love writing against things. I love when there’s an immovable object and then writing towards moving the immovable. Here’s the United Nations, an institution that doesn’t feel shakeable, and writing against it by using its own language and turning it against itself… it’s very cathartic.

Tone Madison: Do you feel like you would have been able to access those ideas without using the documents?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: Probably? But they would have felt a lot more personal—and I was already writing the deeply personal poems. I was watching news stories about military cruelties coming out of Myanmar, and I was writing about them. And on several levels, I don’t feel that it’s ethical for me to be writing about people who are on the ground, putting their lives on the line for something they believe in, something they are killed for, from my place of relative safety. But writing against entities like Myanmar’s military government or the United Nations, using their documents—I have no qualms about that.

Tone Madison: You write often about your status as a visa holder, and as an individual in de facto exile. How do you balance that precarious status with the need to address politics in your art?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: The precarious nature of being a visa holder is in and of itself political. It has always been. Of course, this nature has become much more pronounced under this current administration. And I feel trapped—because having a visa, under “normal” circumstances, means that there’s a home country you can always return to. But with Myanmar in the throes of yet another military dictatorship, with a travel ban on my own country, return isn’t currently an option for me. More than that, movement isn’t an option for me. So despite my instinct and desire to address politics outside of my art, I have to be careful about what I say. But my art will never shy away from politics. I can’t afford to.

Tone Madison: You’re known to be very prolific and to be a master of so many different genres? What projects are most exciting to you right now? Do you also see them as a form of fablemaking?

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: I’m in a lull right now. Burma Girl—a poetry chapbook responding to Rudyard Kipling’s “Mandalay”—is coming out next year, too, so I’ve been in the midst of prepping for the release of Fablemaker and going through final proofs of Burma Girl. But I’m passively working on my short-story collection, which hopefully I will have fully drafted by the end of the year. The stories are about Burmese women who are contending with military, patriarchal, and religious violence and the ways in which they resist as far as they are able to. It sort of bends towards speculative fiction, drawing from folktales and featuring mythical creatures. It’ll be fun when, you know, I’ve finished it.

Tone Madison: What do you want readers to get out of the experience of reading Fablemaker, even if they might be more distant from these life experiences? In your first poem, you beckon folks to tell a story.

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu: At its core, it’s a book about grief. And I think anyone who comes to Fablemaker who has either grieved something or is grieving something will hopefully get something out of moving with me and the speaker—from “Every time I crack an egg I think of skulls” and the violence of that image, to the final poem where I gesture to survival beyond an ending. But I think, mostly the book is an invitation to a story that you may get something out of, or you may not, and that is perfectly fine. With this book, I’m finally moving away from wanting my poems to do impossible things. It’s more of, “Here is an offering from my life and the things I’ve experienced thus far, and you’re welcome to witness it. You’re welcome to be a part of it.” But I’m not asking beyond that anymore.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.