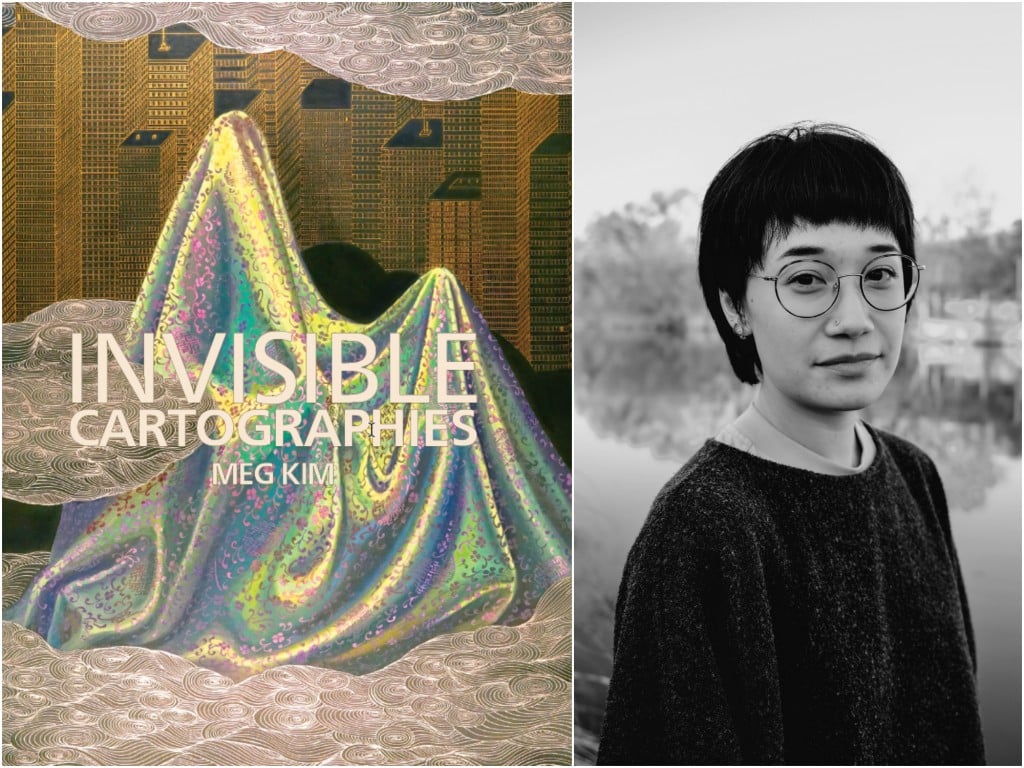

“Invisible Cartographies” lyrically excavates geographies both material and spiritual

Poet Meg Kim probes the limits of the knowledge and language of place.

If there was a word to describe the essence of 2023 UW-Madison MFA graduate Meg Kim’s Invisible Cartographies, it would be lush: in language, in landscape, in memory, in longing. The winner of the 2023-2024 New Delta Review Chapbook Prize, Invisible Cartographies is rooted in place—geographies both physical and psychic made visible only by Kim’s careful practice of excavation, bred by her “mass of wanting.” Spanning the foothills of her Southern Oregon hometown, the city blocks of Chicago, and her paternal family’s homeland of Korea, the poems in Invisible Cartographies are haunted by everything that can be disappeared—whether deliberately through violence or more passively by the passage of time, the absence of knowledge, and the wide maw of silence.

If the poet’s task is that of articulation, then it is one that Kim approaches with diligent precision. Kim is drawn, like most writers are, to affective extremes, but they are disciplined in descriptions, careful not to fall into romanticization where it is not due. For example, in “Incomplete Origin Key,” the hills are not gold (“too lux a word for them”), but urine or tinder. Again, in “Have You Seen the Ghost Flames at Nogeun-Ri?,” the ghost flames are undeserving of “pretty words” like illusory or incendiary. This exercise in restriction makes descriptions of beauty that much more rewarding, like in the poem “In the Road,” where “small white churches” are described as “beacons the color of teeth, / or mourning, emitting / phantom hymns.”

The skill with which Kim wields the knife of the English language stands in direct contrast with—and perhaps, is a way to make up for—their clumsy grasp of Korean. It is Kim’s heritage language, and one they only recently began learning. Meditations on this knowledge gap, along with limitations of translation, illustrate the strain of being a second-generation immigrant wanting to more deeply understand their family’s history and culture. These poems are attempts to bridge that distance, but never do they carry the architectural hubris of assumed success. In “Have You Seen the Ghost Flames at Nogeun-Ri?,” Kim states, “My body is a match soaked in water—the flame of experience cannot live,” and later admits to the fact that their “American mouth” is an “unreliable narrator.”

Straddling the tightrope of what can and cannot be articulated from specific positionalities (“some griefs open sweetly / some griefs cannot be named”), Kim still tends to the seeds of ineffability with tenderness, providing them with the temporary scaffolding of words as a way to honor them. Picking at the fragile “skin of then and now,” out of this wound emerges another temporality entirely: one that can revere the past without rewriting it; one that can hold the imperfection of a present in all of its complexities.

In late June, I sat down with Kim over Zoom to discuss Invisible Cartographies, poetic lineage, their relationship to language, and how we regard ancestral histories.

Tone Madison: You’ve said in a previous interview of ours that you’ve never wanted to be anything other than a poet. When was the first time a poem moved you, or the first time you understood poetry’s power?

Meg Kim: When I was a kid, due to whatever manifestation of neurodivergence, I refused to speak to anyone, especially adults, even my parents. I would be afraid to say anything in class. It took me years to be able to answer a single question, [even] if a teacher were to directly address me, or to even be able to have the courage to interact with kids my age.

I quite literally couldn’t do it. And I remember there was this one girl in my pre-kindergarten class who could already read. One of my earliest memories [was] latching onto that and being like, “I want to learn to read right now.” And I did. I learned and from the time I could read, I began to write stories. Something about the written word made me feel like I could access the voice I felt I didn’t have, even as a five year old who doesn’t have a concept of that.

I think that was when I fell in love with language, and specifically, literature. And then poetry more precisely, I remember encountering it in middle school. And it was more that I fell for its sound. We were reading old British rhyming poetry like Emily Dickinson, and so that kind of drew me in. It was irrevocably in high school that I began to read contemporary poetry and just never stopped.

Tone Madison: Can you talk a little bit about the poetic lineages you are invoking and carrying in your work? Who were some of the poets you were reading while writing these poems?

Meg Kim: I feel like I often struggle with this question, because I think I’ve absorbed many poets that I really don’t end up sounding like even though I know that they had an impact on me. A lot of the poems in this chapbook were written between the ages of 19 and 24. So, two of those years I was wrapping up my undergraduate degree, and because of that, I was reading a a kind of a sponge for everything.

Off the top of my head, I remember at that time I was reading Kaveh Akbar and Paisley Rekdal. And then I was particularly taken with reading [that] I was doing for an honors thesis project on Asian American poetry—specifically Suji Kwock Kim, Kimiko Hahn and, of course, Jenny Xie were super [impactful for] me. And then I was also reading a lot of work in translation during that time, a lot of anthologies on the Korean syllabic form sijo for my thesis, and then a couple others:the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer, Rainer Maria Rilke, [and] Antonio Machado. I think Don Mee Choi was formative for that experimental interrogation of the Korean War and like the neo-colonial relationship of the United States to the peninsula.

Tone Madison: You hail from the West Coast, and specifically, the foothills of Oregon. The geographies of this region are palpable throughout the book. Has living in the Midwest for an extended period of time influenced your writing at all?

Meg Kim: It definitely started with the poems about the West Coast, but I think this book ended up almost being 50/50—it kind of spans geographies. When I was structuring it, I kind of thought about it in terms of the West Coast, my current life [in the] Midwest, and then the mythic country of origin, or the imaginary Korea of the speaker.

I think the poems in this chapbook came at the very beginning of [my] feeling like I could actually write about the West Coast and the places I grew up in, which is something I was really averse to doing for the longest time. I think part of the reason is that when I was growing up on the West Coast, a lot of poems I read by Asian people were set in urban places for whatever reason. And I felt like that’s what I had to write.

In “Where Are All the Gay Poets?” by Bruce Snider, he talks about how, when he was young, all the gay poets that he was reading—specifically O’Hara—they write about cities. So he felt like he had to write about cities. And I feel like I had the same kind of thing, except with my race and not my sexuality. All’s to say, I felt like finally, in my adult life in the Midwest, that I was given the distance I needed to look back and actually want to write about the places I grew up in.

Chicago also finds its way into this book a lot, almost in equal measure, because it’s been such a formative landscape for my adulthood and independence. Also I think notably, this is the first time in life where I have actually lived around other Asian people and people of other ethnic and racial backgrounds. And I think because this is a book that interrogates racialized experiences, that was really important.

Tone Madison: You interrogate narratives about immigration, the American Dream, and assimilation in many of your poems. For example, in “I Search for Koreatown” you write, “[…] the state meets / the white / of my eyes / and sees no alien / only animal / of their making.” Talk a little bit more about your perspective on these ideas and how you’ve experienced them.

Meg Kim: Especially in my writing, I feel like I spent so many years pushing against the narrative or expectations of whiteness—both my own inherited whiteness and that of my imagined audience or my real audience. I wanted to write a book that spoke back to that, and spoke back to all these different positions I’ve seen other writers take.

I wanted to enter the conversation, basically, and because I write a lot about my family, I also wanted to meet the complexities of being a person living several generations removed from the immigrant experience without reducing it, or reducing my family’s experiences. I think often, the parent figure or the grandparent figure becomes more of a symbol than a person in a lot of things. Whether or not I was successful in not making them into that, that was the attempt. I wanted to push back on that while also acknowledging the things I did believe, or do believe, and am unlearning about the American dream.

Tone Madison: Your manuscript is rich in setting, and there is a very strong “I” who often makes declarations in your poems. And yet, I feel as though the physical body is secondary to the book’s project. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Meg Kim: I think a general weakness—which maybe can be turned into a strength—that I push against as a writer is the tendency to “be cerebral,” whatever that means. As a person who does tend to be in their head a lot, and also has the tendency to obscure the speaker, for better or for worse. I think for this chapbook, the lyric “I” is one that I wanted to use to position myself and to take ownership of my own perspectives and not impose them on anyone else. But I also really wanted an expansive “I,” or a “you.” I switch between pronouns a lot. It ended up helping to accomplish this idea of expansiveness or plurality of voice. I think I was searching for the same resistance to the dominant voice, especially when I was taking up the voices of the folktale characters. It’s a book that deals with the idea of invisibility, however you choose to interpret that. It makes sense that the “I,” or the body, is elusive. I really wanted the landscapes and the forces of history to be more corporeal and more agential than the speaker because I think that speaks to a lot of the themes.

Tone Madison: You straddle this really fine line between that which can and cannot be articulated. How has learning your heritage language affected how you think about language as a whole? Its possibilities and limitations?

Meg Kim: I like this question in part because I feel like I thought about it a lot. I assembled the book while I was taking beginner Korean classes. But I think, for me and for a lot of diasporic second and third generation Asian Americans who are not raised speaking their heritage language, maybe the parent figure or the grandparent figure can become this symbol and this superreal vessel of loss and connection to family, ancestors, country of origin. In my case, as someone who was raised to speak only English, I felt that [learning Korean] was my key to belonging and that [it] would help me access silences or help me soothe alienation. I feel like it was, “If only I can do this, then I will have these things that I felt like I lacked.” Now I know that’s not true. That’s an impulse that’s complicated by a lot of things, including but not limited to English language as a tool of empire, the very real barriers that are faced by people who don’t speak English in this country, and that me learning Korean is not going to solve lack or unbelonging or anything that’s a product of all these things larger than myself.

I may not learn [Korean] even in my grandmother’s lifetime, who is functionally the only person in my life I would ever need to speak Korean [with]. I think [in] learning my heritage language as an adult, I found that the act of actually learning to speak a completely new language as a monolingual person was more transformative than the actual language. It’s pretty mind-blowing that grammar, syntactic structure, pronunciation, and level of formality are completely beyond the ways that I am currently capable communicating in. I think that was really generative for how I interacted with the English language, and a lot of the poems at least referenced that experience.

Tone Madison: You write about your family’s relationship to war and imperialism’s protracted trauma. War and its horrors seem so commonplace in this geopolitical moment. What do you find is poetry’s role in a time like this?

Meg Kim: I’ll start with the very tangible and then bring it out a little. There is a poem in this book that is explicitly about the Korean War, and that was a hard poem for me to write. And it’s a poem I swore I would never write because I feel like one of the guiding questions of the book is, “What can I and what should I claim, and what can I trouble, and who am I to fill in these gaps?” And the poem takes a ton of forms. It is the most formally sprawling. I think that those many chaotic, different forms reflect the trouble I had finding a way into [the poem] because in the end, it was what I didn’t know about my grandparents’ experiences during the Korean War that ended up being the motor or the engine of the poem. Like, what do I not know? And then I think—and this was the reason I had avoided writing in the past—it also forced me to acknowledge my position as a citizen of the nation that began a proxy war in Korea and continues to occupy Asia and the Pacific and funds the genocide in Gaza as we speak. Obviously my grandma’s experiences are the histories that I come from, but this is my own position, and I think it’s my responsibility to have to navigate both of those things. I can’t only, on the page, claim generational trauma, right?

I hope that a lot of the poems in the book leave room for the possibility that I shouldn’t have written those poems. I think that I want that to be a question. All that [is] to say, I find myself less and less under any sort of romantic notion or illusion that poetry can really do anything in a time like such. Whatever people’s position is on that, I think what I can firmly say is whatever is done on the page should also be given tangible action: It’s doing fundraisers; it’s poets who are organizing and standing for their communities when it actually matters, with their bodies, on the ground, in the ways that they can.

Tone Madison: To wrap things up, I’d love to know if you’re working on a new project right now. Are you asking new questions, taking old ideas into new directions?

Meg Kim: I’m working on what I hope will be my first full length manuscript, and I feel like in a lot of ways, it was originally an extension of the trajectory of the chapbook. And then somewhere along the way, I was like, “I’m tired of this.” I think it was Danez Smith, in conversation with Franny Choi and Monika Sok who said that there are poems that you have to write through to get to other ones. And she was talking about specifically in the context of second generation debut books, or Asian American debut books. I feel like these were the poems that I had to write through. And then I was like, “I could keep going, but I don’t want to.”

[My new project] is a bit more of a conceptual project. It focuses very specifically on the histories of the valley in which I grew up, as well as themes of deviance and resistance. I’m trying to really move beyond my comfort zone and lean more into strict research, docu-poetics, and ecopoetics, whatever that means to you. I’m moving beyond the ease or lull or prettiness of a lyric. I think formally, I’ve decided to give myself more constraints because Invisible Cartographies was inspired by spareness of image or line on that level. It’s pretty sprawling in form. I think that contrast of the restraint of the image but lack of formal control worked for this, and I really want to do something really different. I want to give myself a different kind of container and see what that does.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.