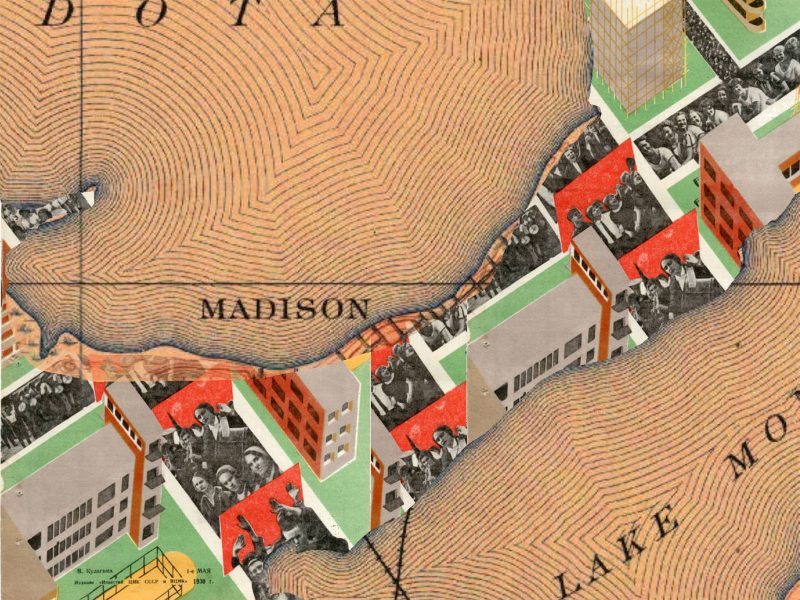

Has Wisconsin learned from the almost-stolen 2020 election?

Activists and voting officials reflect on their tactics, amid a fresh wave of disinformation and tampering.

Activists and voting officials reflect on their tactics, amid a fresh wave of disinformation and tampering.

On September 23, the City of Madison Clerk’s Office released a statement about a data processing error that had caused around 2,000 voters to receive duplicate absentee ballots. The office was contacting those voters, telling them to only submit one ballot and destroy the duplicate. As a backup, absentee ballot envelopes have barcodes tied to individual voters.

The official statement from the Clerk’s Office currently reads: “Because the duplicate ballot envelopes have identical barcodes, in the unlikely event that a voter submits two absentee ballots, only one can be counted. Once that envelope barcode is scanned, the voting system does not allow a ballot with the same barcode to be submitted. The voter is also marked in the poll book as having submitted their absentee ballot as another safeguard against the voter submitting a second ballot.”

You would think that would be that. But U.S. Rep. Tom Tiffany, who represents Wisconsin’s northernmost Congressional District, the 7th, latched onto the story. The day after the Clerk’s office’s statement was released, Tiffany blasted the story on Jay Weber’s talk radio show on WISN (yes, that Jay Weber, who called Gus Walz “a blubbering bitch boy”), NewsMax, and social media. On September 26, he posted on Twitter a photo of absentee ballots and the caption “NO BARCODE.”

And sure, the original version of the release did not specify that the barcode was on the envelope, not the ballot itself. But Tiffany ran unsuccessfully for state Senate in 2004 and 2008, was first elected to the Wisconsin state Assembly in 2010, then moved on to the state Senate in 2012 before being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 2020. He’s on the ballot for reelection on November 5. So he and/or someone in his office knows how elections work by now. Or at least that the barcodes are on envelopes.

If that wasn’t enough, the following weekend (because there’s some law of the universe dictating that Wisconsin elections have to be goofy as hell) Wausau Mayor Doug Diny donned a hard hat, put the City’s absentee ballot dropbox on a hand dolly, and carted it away.

These incidents feel like a first shot across the bow, like the velociraptors throwing themselves at the electric fences in Jurassic Park, looking for weaknesses. And I, for one, am a bit worried that we could see a repeat of the 2020 attempts to overturn the election in Wisconsin. For one, we’re still fighting over absentee ballot dropboxes, which were used for years and apolitical until the pandemic. Republicans’ failed scheme to derail the electoral vote with fake electors originated in and spread from Wisconsin, and while the people behind it have faced some consequences, none of them are in jail. Hell, one of the fake electors, Robert Spindell, is still on the Wisconsin Elections Commission. Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson, who participated in the scheme and lied about it, was reelected in 2022. Former President Donald Trump’s attempts to overturn Wisconsin’s 2020 election results in his favor were thwarted only by a few crucial votes from Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Brian Hagedorn. In a departure from his altogether heinous right-wing record, Hagedorn joined with the court’s liberal justices in a series of 4-3 rulings that blocked Republican attempts to throw out votes from Milwaukee and Madison and tamper with the recount process.

So, how worried should we be about this election?

Jay Heck, executive director at Common Cause Wisconsin, a pro-democracy, voting advocacy organization, says he’s not surprised by the antics of Tiffany and Diny. But Common Cause and other pro-democracy organizations have learned from 2016 and 2020 and “we’ve never been better organized,” Heck says.

“I feel good about where groups like ours are, because we’re expecting the worst. And hopefully the worst won’t develop, but if it does, I think we’ll be ready,” Heck says. “We have election protection people recruited, we’ve got attorneys to be able to go into court and challenge wrongful obstruction of voting. And so part of it’s defensive, but part of it is also anticipating things that could happen.”

Heck points to significant changes over the last four years: to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which now has a liberal majority, and to the Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC), where Spindell does not seem to wield much influence over his fellow WEC Republicans. Heck also points to an increased willingness to push back against extremists. Days after Diny’s stunt in Wausau, the dropbox has been returned to its rightful place, and Diny’s actions have been condemned by Wausau City Council President Lisa Rasmussen and City Clerk Kaitlyn Bernarde.

Wisconsin Democracy Campaign (WDC), a nonpartisan watchdog group, has been helping Wausau residents respond to Diny’s act. On Wednesday, Wausau residents filed a complaint with the Wisconsin Department of Justice to investigate with WDC’s help. “It means something when a mayor does that, and there needs to be accountability,” says Nick Ramos, WDC’s executive director.

“We’re living in a time where myths and disinformation [are] running rampant. We’re living in a time where we’re hearing more and more cities just shutter their dropboxes altogether, because they feel the pressure of bad actors and election deniers coming in and wreaking havoc on them, and they just don’t want the problems,” Ramos says. “We have to be fighting for voting access. We need to be fighting to make sure that every voter—I don’t care what political party you are affiliated with and what your beliefs are—I want to make sure every eligible voter can cast a ballot that counts. And when you see a sitting Mayor [remove a dropbox], it causes a chilling effect.”

Ramos says it’s also really important to act, because many local politicians don’t think voters are paying attention or are going to push back. Diny’s act is “almost like a warning shot, or a test balloon,” he says.

“Like, ‘Well, let’s see if we can put our toe in the water a little bit. If we don’t get any resistance, then maybe we can go a little bit further. Maybe we can take another foot or two into the pool, and then maybe we can just get all the way in and just do the most anti-democratic things that we like, because no one’s really paying attention or nobody really cares,'” Ramos says. “And it’s like, ‘Hell no.'”

Disinformation about dropboxes has also prompted vigilantism and voter intimidation. Kyle Johnson, partnerships director at All In Wisconsin, says his organization has heard from its partner organizations across the state about civilians surveilling dropboxes in certain communities, “which is obviously not something that should be encouraged or even allowed, because that creates that air of intimidation,” Johnson says. “Am I safe? Who is watching me? What are they watching me with? Do they have weapons? Because we know that’s a problem, unfortunately enough, in today’s day and age in our country.”

Technically this surveillance is not illegal, but “people know what they’re doing is wrong,” Johnson says, so All In Wisconsin’s response is to make public who they are and what they’re doing.

“We have to make sure that people are held accountable to the actions that they’re having,” Johnson says. “So that’s how we’re trying to meet the moment.”

All In Wisconsin has also been monitoring safety threats and working with local law enforcement in communities across the state “to know what are y’alls plans in the event that something happens at a central count location or at a polling location?” Johnson says. “How are you all going to keep people safe? Because that is your job.”

“But for the state of this election, I would say we feel we’re operating with a sense of caution, because we want to make sure that we’re prepared,” Johnson says. “But at the same time, we do feel prepared.”

Tiffany’s statements were also met with significant pushback from his own party, indicating a shift in Wisconsin Republicans’ appetite for Trumpian voter disinformation. State Rep. Scott Krug (R-Nekoosa), chair of the Assembly Committee on Campaigns and Elections, told Wisconsin Public Radio that “everyone can dial back the rhetoric a bit.” Krug was selected to replace former Rep. Janel Brandtjen (R-Menomonee Falls), who used the committee to platform and push election conspiracy theories, and to enable former Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman’s absurd “investigation” into the 2020 election. When Trump allies ran afoul of Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R-Rochester)—not for spreading disinformation, but for supporting Vos’ opponent in a Republican primary—Brandtjen got the boot. Krug has been a much more measured chair of the elections committee.

Krug admitted, to an extent, that the frenzy is political, and he recalled a similar incident during the August primary in Douglas County that didn’t attract anywhere near the same degree of attention.

“I think the challenging part of it is that it came from Madison, you know,” Krug told WPR. “If it came from Sheboygan, I don’t know if it’d be as exciting to some people.”

City of Madison spokesperson Dylan Brogan agrees with Krug’s assessment. One of the challenges of fighting disinformation “is that people latch on to something, and despite whether it’s true or not, just start making assumptions,” Brogan says. “’Oh, look! See this happening, and obviously, you know, it’s Madison, Wisconsin. They’re trying to cheat us.'” (Brogan previously contributed to Tone Madison as a podcast producer and writer, during his time as Assistant News Director at WORT.)

Fighting disinformation is tricky, because on one hand “you don’t want to amplify things that are untrue or or give more attention to something that is just clearly a bad act, or the motivations here are not really about what’s going on in Madison,” Brogan says.

“So, are you making it worse by responding? I think those are the kind of things that we judge on a case-by-case basis,” Brogan says. “And moving forward, I think at the end of the day, it’s always like, ‘Hey, we are always happy to answer questions here in Madison, wherever they’re coming from. We’ll show our work. We’ve got nothing to hide here.”

Jay Heck emphasizes that, despite the positive changes of the last four years, he doesn’t want to downplay the risks or come off as “Pollyanna-ish.”

“I’m wary,” Heck says. “I’m obviously nervous, like everybody else who knows what they’re going to pull. But I also feel more confident, really, than I did probably in 2020 because I just think we’re better prepared for it.”

Johnson also wants people to think beyond the November Presidential election and focus more on how communities at the local level can work to bring about the big changes needed in this country. That includes addressing outsized corporate power and influence in politics, income inequality, our broken healthcare system, the military-industrial complex, militarization of local police, and other issues.

“Because that’s part of the reason why we’re in some of this craziness in the state of our politics right now, unfortunately enough,” Johnson says. “Folks in my line of work, we want people to vote, but we don’t illuminate enough and educate enough and build a community in relation enough to let people know, ‘All right, you voted. But you’ve got to show up to the school board meeting, and the common council meeting, and you have to write your senator, and you have to call your representative. These actions definitely matter, and honestly, cumulatively, they matter as much or even more than voting.’”

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.