Functional play in the abstract: an interview with game studies author Peter McDonald

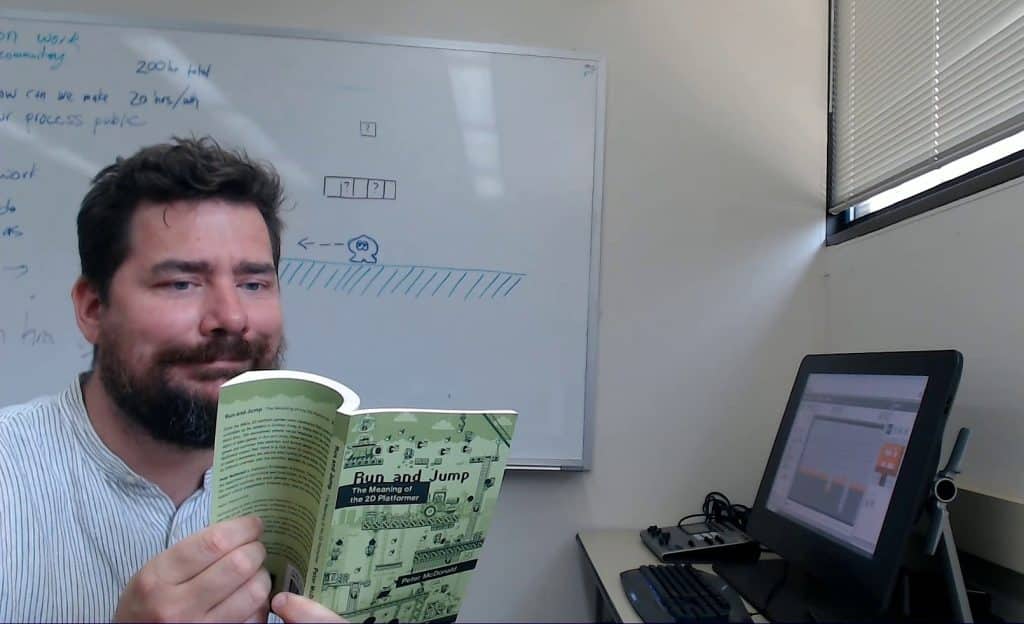

The UW–Madison assistant professor discusses the philosophies behind his new book, “Run And Jump: The Meaning Of The 2D Platformer.”

The UW–Madison assistant professor discusses the philosophies behind his new book, “Run And Jump: The Meaning Of The 2D Platformer.”

Small-scale indie-video-game development has now caught up to all those AAA studios that so swiftly churn out franchises and remakes. Part of the reason for that in the past decade-plus is simply the fact that independent developers and studios aren’t jammed in the cogs of hierarchical corporate interests. They aren’t burdened by unwieldy scale. An inherent intimacy permeates the spirit of these games, some of which Tone Madison has profiled over the years. Often working with more basic code and 2D design templates, many of these games attempt to capture the distinctive impact and kinetic relationship of the most significant cultural era for video games, the 1980s.

With his new book, Run And Jump: The Meaning Of The 2D Platformer, UW–Madison Assistant Professor of Design, Informal, and Creative Education (D.I.C.E.) Peter McDonald aims to create a “continuity between generations of players” in the same way platformers have as the most essential skill-based games in the medium. This pixel-graphic genre of fast-paced and addictively tricky games rose to almost immediate ubiquity with the 1985 release of Super Mario Bros., which was bundled with the original Nintendo Entertainment System. Innumerable imitators and innovators have flourished through nearly 40 years of evolution since, from ‘90s mainstream titles McDonald cites (Sonic The Hedgehog, Donkey Kong Country) to the last two decades of underground deconstruction by the very minds who grew up absorbing those very platformers. (See/play: 2008’s Spelunky, 2010’s Thomas Was Alone, and 2015’s Strawberry Cubes for a smart sampling of the genre’s recent evolution.)

However, McDonald’s game-studies book, released this past February through MIT Press, is less interested in a linear tracing of history. It instead offers design parallels between personally meaningful games, guided by his philosophical lens on their mechanics and functionality. Run And Jump is a dense, sometimes challenging, but enriching read for anyone who’s wondered what might be behind the eight- and 16-bit-rendered veil.

McDonald’s text further provides real insight into why people are so drawn into game worlds that bridge the past and present. He concludes each of Run And Jump‘s four chapters with a series of brainstorming design exercises that tap into the significance of childhood memories on aesthetic preferences, design functionality, thematic tone, and more. While these exercises have a practical application, they also help illustrate the translation process from abstract sketches to fully rendered, interactive art.

Run And Jump starts by peeling away layers of meaning behind the simple action of the jump, integral to traversal and progression through the level design templates of platformers. It evokes expectations about potential pitfalls and outcomes. In its mediation of free motion and constraint, jumping in a game signifies a range of emotions—most notably glee, craftiness, and freedom, as McDonald writes in his first chapter. The following section looks more resolutely at the logic of game design itself and non-Euclidean game spaces. McDonald explores five oppositions that organize space and establish the dynamics of player choice, including the binaries of horizontal and vertical, narrow versus open, and stationary versus scrolling.

McDonald’s third chapter is the text’s most profound extrapolation, particularly for anyone who has pondered the nature of the enemy and conflict in games. Here, he explicitly hones in on the philosophy behind enemy designs and implementation. In this chapter, McDonald offers truly moving revelations about the implied personality of bosses and the ethical dimensions of engagement. By the fourth chapter, he argues for the metalanguage of games—especially in the context of the modern envisioning of platformers. He also emphasizes the notion of authorship embedded in collectibles, secrets, or easter eggs (a now universal term that actually originated in gaming).

McDonald’s writing voice is pretty strictly erudite in laying out his arguments and frames of reference, with recurring appeals to structuralist signs/signification asserted by 19th century Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. And yet McDonald’s approach, by the end, is also not without hints of impishly fun subtext and adages like “To search for secrets is to be in thrall to an oblique desire than runs tangential to winning or losing.” A couple pages later, he posits an analogy that casts the game secrets-hunter as a “modern-day medieval Christian monk deciphering the book of the world.” McDonald is not only someone delighted by the worlds of games, but thinks within them through his language and suppositions, conveying the social value of games as a definitive art form. In his writing and teaching, he becomes a living conduit between generations of players and game-makers.

In late June, Tone Madison sat down in person with McDonald in the Teacher Education Building on UW campus to discuss some of the principles and observations that ground Run And Jump (in addition to some other playful inquiries). Our conversation dug into a myriad of subjects, some directly pertaining to the text and some others as digressions, but all creatively emanating from it in one form or another. The transcription below has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tone Madison: In rough percentages, how much hands-on work do you have with students, and how much of your job as an Assistant Professor is strictly research? Or do you find that they’re inextricable when we’re talking about research in the gaming medium being literally hands-on?

Peter McDonald: Yeah, they’re maybe not inextricable but they feed into each other so clearly for me. Before I came to Madison, I was teaching at DePaul [University] in Chicago. This book came out of a class I was teaching there, kind of directly, on 2D platformers where students were wrestling with some of the technical sides of how to implement their ideas for games. They got kind of lost in the process of it. They wouldn’t know how to make a design decision. “What would a good jump be like?” Because that’s a very general term. And so in conversation with the students, I started thinking about how they could translate their ideas for what the game should feel like or mean into those more formal terms.

Here in Madison, a lot of my work is teaching undergraduates introduction to game design. I teach a couple of different game design classes, but my big bread and butter is the introductory course. We spend a lot of time making lots and lots of things. I always tell them, “You’ve got 100 bad ideas you’ve got to get out of your system before you get to the first good one.” [laughs] And so we just make a lot of games in a very quick amount of time.

Tone Madison: So, like a game jam sort of style?

Peter McDonald: Yeah, even quicker. Every class is two and a half hours; we make a game within that class time. Outside of class, [students] are also making digital games. So, in class, they have a prompt where they have to take a puzzle. Say, a Rubik’s Cube. Now you’ve got to translate what makes that puzzle fun and that kind of puzzle using a deck of cards or pieces of string or something else.

Tone Madison: Yeah, that’s a little daunting, I would think. Creative ideas are there but need to be further developed. Is that kind of the initiative?

Peter McDonald: Absolutely, to get people to take the risks of thinking through those ideas. And they do it in teams, so no one person is wrestling with this as a problem by themselves. All of these are not just “make the best game that you can,” because there’s no such thing as the best game. It’s “how do you take something specific to and something interesting about the Rubik’s Cube and bring it into a new context?” Taking the abstract feeling and working with that.

Tone Madison: Run And Jump is part of MIT Press’ “Playful Thinking” series of books about video games. I haven’t read or familiarized myself with the others. How many other books are in this so far?

Peter McDonald: It’s been around for a little while. There’s some really wonderful books in the series [21 as of August 2024]. The one that has been a deep inspiration for me is Uncertainty In Games by game designer and critic Greg Costikyan, [which] I think is really beautiful.

Tone Madison: You start this text from the basic mechanics of 2D platforming games, and the meaning behind “language of action.” On page 24, you analyze the goal of the jump, which is practiced in-game until it’s an habitual action. When I read that, it reinforced the idea of virtual action simulating a skill we practice in our reality in order to succeed. It’s kind of like dreams mentally preparing us for day-to-day challenges. Jumping off of that, literally—[laughs] sorry, metaphorically jumping off of that, I’m interested in your take on the philosophy of thought behind games and their microcosmic or macrocosmic purpose. Do you think this was a key factor in the 1980s when 2D platforming design was still in gestation, forming its identity? Or is this forethought something we’ve developed intellectually in the past two decades of our type of media-overload culture?

Peter McDonald: Do you mean the specific meaning of jumping or wider use of games?

Tone Madison: Wider use, but could apply to both.

Peter McDonald: That’s, in some ways, a really complicated question.

Tone Madison: [laughs] See, this is where the loopiness comes in, when I was writing some of these questions at 2 a.m.

Peter McDonald: Some of my other research [involves] thinking about a larger transformation in American culture, where games and play became really central to it, before video games. I do some research on art movements of the 1960s that experimented with a whole range of wacky games. Games without any rules. Like, [for example], you get a deck of cards and have to play a game with it but it doesn’t tell you how. [laughs] I have the deck somewhere around here if you want to see it.

Tone Madison: Is Andy Warhol involved in this at all? [laughs]

Peter McDonald: He’s very close to it, but it’s more like John Cage and [Fluxus artists] like that. This is before video games are on the scene. There’s a whole range of other transformations. Role-playing comes into classrooms for the first time in the 1940s. Or there’s pinball machines everywhere that are non-computational. This is just a smattering. But I think there’s a big shift towards playing games as deeply meaningful things in American culture, and then video games captured that energy and sent it in a particular direction. So I don’t think it’s video games that are causing this, I think it’s actually something deeper.

At the same time, I don’t think a lot of this is conscious. When designers [like Shigeru Miyamoto] are making Mario jump in the particular way he’s jumping, I don’t think he’s consciously like, “let’s make Mario a metaphor for something” or even necessarily using the language that I use to describe the adjective qualities, like Mario is slippery. Maybe he’s talking about slipperiness, but a lot of this can happen by tweaking a number and never talking about it at all. So you’re getting an implicit sense of what Mario should feel like when you’re designing a game. But I think there’s a lot of stuff happening there, on this linguistic side. This meaningful side of designing games happens at an unconscious level.

Tone Madison: I’m curious about your perspectives and choices behind your writing process of this. I’m thinking of templates for platforming design as they persist today, dating back to Shigeru Miyamoto’s vision with Donkey Kong and Super Mario Bros. in the early-mid ’80s. Another game you talk about at length in the third chapter about “Philosophy of the Enemy” is Mega Man X. I’m wondering if you would consider the element of the “enemy” to be fundamental to that evolution to platforming design when that game arrived in 1993/1994 in North America? Or is there another game from the Super Nintendo and Genesis era that you would consider more crucial?

Peter McDonald: To that particular evolution?

Tone Madison: Yeah, so like, from third to fourth generation, from Nintendo to Super Nintendo, is there a leap?

Peter McDonald: There are a few other games in the third generation—Mario has always had enemies, and Metroid is probably the thing in that generation that prefigures Mega Man [on the NES] the clearest in that way. But I do think that Mega Man X is the place where this idea of enemies evolves another layer. The way that it separates out different kinds of enemies and uses bosses as so much more evocative and personal. When you meet these bosses, it feels like they’re people. There isn’t quite that same level of detail in the third-generation consoles. All of this is kind of an evolution, where people are constantly playing other platformers and borrowing ideas and transforming them for a new context. Some of that is reliant on the technical hardware. If you have bigger sprites, you can make them more expressive. But a lot of it is an ongoing design conversation that isn’t about the technical limits so much.

Let me give you an example: I make a bunch of things for a community that makes contemporary Game Boy games that you can play on the old [8-bit] hardware. They’ve developed a whole bunch of great tools that make it really easy to program and design your own Game Boy games. But they’re still working with the same technological limits as the original system [1989-1999]. Nonetheless, you can see games made for the Game Boy today use all sorts of design ideas that’ve evolved over the past 30 years—Wow, I feel old. [laughs]—since the Game Boy was originally released. And so platformer games, at least for the Game Boy today, look much more like platformers for any other system today than they do original Game Boy games.

Tone Madison: Do you have a favorite classic and/or modern 2D platformer? I guess the deeper question is, if you have two games you’re gonna cite in this answer, do these games converge or diverge in terms of what they attempt to do and communicate?

Peter McDonald: I think diverge. But in some ways, all [those] do the same or similar-ish things. Whereas my favorite contemporary platformer is Rain World (2017), which I cite a couple of times at the end [of chapter two, on pages 70 and 71].

Tone Madison: Mm-hmm, I put that on my PSN [PlayStation Network] wishlist thanks to you. I don’t think I had heard of it before.

Peter McDonald: It’s such a strange game, which is why I like it. It doesn’t care about you in a way. You’re a thing called a Slugcat, part of a wide ecosystem. The game simulates the whole ecosystem all the time. So, there’s things you have to eat, and things that will eat you. And the game is constantly updating those—they all have a life outside wherever you happen to be wandering in the scene. It’s a huge world, and every 15 minutes, torrential rains will fall and kill everything that’s not hiding in a burrow somewhere. You have to eat enough to survive, go and hide in the burrows, avoid things that are evolving to kill you. And then within that, you still are sort of on a quest, a larger narrative structure. That sense of being a fragile creature in a huge, anonymous world is like nothing else I’ve had an experience of in a game. In terms of classic games, though, the pleasures are just so different. I love the twitchy action of some of these old games.

Tone Madison: Is that where they came up with the name “Twitch” for live-streaming? [laughs]

Peter McDonald: I think so, yeah. [laughs] Picking a favorite is gonna be difficult. I’m not sure this is gonna be the best game, but one that’s deeply important to me is a game called Joust, which is a classic arcade game. But it’s one of the first two-player platformer games. My brothers and I would spend a lot of quarters on it when we had the chance. It has a soft spot in my heart, even though it’s super simple. The basic mechanic is that you fly on ostriches, and you can hit the jump button to flap. Whoever hits [the other], and is higher when they hit, wins the joust.

Tone Madison: OK, I don’t think I’ve played it, actually. But I’m sort of familiar with the mechanics.

Peter McDonald: It’s really that uncertainty as you’re arching towards each other—that moment is one of the purest versions of the pleasure of not knowing if you’re jumping correctly or not.

Tone Madison: So, yeah, those are vastly different games. You’re highlighting the range of what a game can communicate. There’s obviously 30-some years or more between those two games.

Peter McDonald: Almost 40 years between those two games.

Tone Madison: I’ve talked about historical perspective here, and just trying to get a little more behind that, but I wouldn’t say Run And Jump is really about history. It’s about providing design perspectives and laying out exercises for people who are aspiring coders and pixel-art directors. I was intrigued by your analysis of personality and humanity in the third chapter, you get into philosophies of life, death, and value confronting the player. This sentence really struck me: “By establishing an economic relationship with the player’s time and effort, the abstract pixels inherit a little bit of the player’s own humanity,” and then you offer a bit more that builds on that.

Do you think gamers have traditionally been attracted to platformers despite this, or in your experience, is it something that’s willingly embraced—the violent game economy being a “healthy” way to exorcise our destructive human nature? We’re not really dealing with photorealistic human enemies in 2D games, but even in their fantasy worlds, they’re still reflecting a certain humanity. Because these are games created by and for humans.

Peter McDonald: I think you’re getting at this already. I don’t think there’s any direct translation of the “violence in video games” debate to platformers.

Tone Madison: Right, yeah. But they are violent. [laughs]

Peter McDonald: I absolutely think they’re violent, but they’re not violent in the same way a first-person shooter is violent. We’re not asked to—there’s always a distance between us and the avatar that is collapsed in the first-person camera.

The things that are on screen are almost always kind of silly. There’s an inherent cartoony-ness to platformers. That is partly the camera angle that echoes slapstick, turn-of-the-century—there’s some Charlie Chaplin films that use that same camera angle and some Buster Keaton films that have him running across [a landscape] as he jumps over fences and slides under women’s skirts and things like that.

Tone Madison: I’m wondering—back then, the footage was shot at a different frame-per-second rate, 16 to 18, and projected between 20 and 24. Maybe I’m wrong on that, but the way it appears is sped up.

Peter McDonald: And the sideview shot. Cartoons use this all the time, right? I think there’s something cartoony, unavoidably. Even when people want to do something serious with platformers, they end up being a bit too cartoony. And so that undermines the sense of violence, and makes it more like cartoon violence. If [Hector] blows up Sylvester, or if the coyote falls off a cliff, that kind of violence is about something different than shooting somebody in a first-person shooter. I can’t say exactly what cartoon violence is all about, but some of it is about the inevitable survival of destruction. That we can hurt each other and come back from it. Roadrunner and coyote are always gonna be in a relationship somehow.

Tone Madison: Now I’m thinking of—there’s a Simpsons episode, where Marge confronts some TV executive [correction: Itchy & Scratchy Land suit] about the violence in Itchy & Scratchy cartoons. And he says something like, and I’m paraphrasing: “We show the consequences of violence in everyday life.” And Marge says, “When do you show the consequences?! On TV, that mouse pulled out that cat’s lungs and played them like a bagpipe, but in the next scene the cat was breathing comfortably.” And he says, “Just like in real life. Hey, look over there!” And runs away. [laughs]

Peter McDonald: [laughs] Yeah, exactly. There’s something in cartoons connected to a childhood wonder of “will people still be there if we’re angry?” If we throw a tantrum, will our parents still return and survive it? Cartoons are a way of reassuring us that [they’re] still gonna be there. I think something about platformers captures that, too.

Tone Madison: It’s not really tapping into our penchant for—if I’m playing any of Bethesda’s modern Fallout games and using the V.A.T.S. system to target and shoot individual limbs, there is something satisfying and cool about that kind of Matrix-esque bullet-time. You’re not gonna see that in a platformer. It’s indulging something, an impulse, but not that.

Peter McDonald: I think you can play a first-person shooter and take out your anger. If you had a shitty day, sometimes that’s a good way to do that. If you play a platformer, you’re not gonna get rid of your anger. It’s gonna make you way more frustrated, because you’re probably gonna die a ton of times. There’s a different set of emotions that go with the violence of platformers. You don’t get to see your own death in a first-person shooter, and your death is usually kind of annoying. [Editor’s note: Although, in the modern Fallout games that were referenced, you actually do. Though, it does have a cartoony, ragdoll effect.] In a platformer, if you play Super Meat Boy, you’re dying thousands of times in that game. And it’s kinda fun. [laughs]

Tone Madison: Yeah, that’s true. [laughs] I think that’s why I gave up on that game. Well, there are so many levels in that game.

Peter McDonald: Yeah, there’s a lot. But seeing your character, not somebody else, get sawed off in some weird way when you accidentally jump the wrong way in Super Meat Boy, that’s part of the pleasure of that game.

Tone Madison: So, it’s like creative death or something. Trying to think of what that would be termed as.

Peter McDonald: A little bit more masochism rather than sadism.

Tone Madison: OK. [laughs] So, it’s really just a distinction between masochism and sadism.

Peter McDonald: [laughs] I’ll stand by that.

Tone Madison: In your fourth chapter, “Every Game Is Two Games,” I really love how you frame the sort of secret components of narrative in 2D platforming games that convey literal and symbolic changes through mechanics. To me, it’s a core distinction of this medium of design and creation, which separates it from cinema. You can use an example of power-ups, which “give the designer the ability to create dynamic and changing characters out of otherwise static avatars” that “tell the story of [a character’s life].”

But what’s interesting here, is that with cinema, the narrative components would seemingly be the primary and initial drivers of the writing and shooting/filming processes. But in the context of developing a 2D platforming game, narrative probably would not be first prioritized. The mechanics to a narrative might be there, but power-ups, as a catch-all term, is an aspect that would come later in the process of development.

Is that something you’d agree with? And do you have any further thoughts on how game development is perceived broadly? Subtleties like this can’t really be understood unless you’re playing something for a sustained period of time.

Peter McDonald: I agree. There are a couple parts I want to touch on with this. Generally, I would say that is true [with] how games get designed. With some other genres, narrative is much more central; but [in] 2D platformers, by and large, narrative is often an afterthought. Complicating that is just the fact that games are made by huge teams of people, and different chunks of games have core creative leads. There are directors in the sense that there’s a director in film, but the director in games delegates a lot more of the creative control of different aspects to team leads. That means, even if there is somebody who wants to develop a coherent narrative, it becomes a little harder to map it across these different chunks. So there’s a narrative team, and they may not be directly on the same page as the team that’s making the character jump in a particular way.

Tone Madison: Also just two very different skillsets.

Peter McDonald: Yeah. All of that is partly why I think [Run And Jump] is an important book to write. There are, already, I think—I’m trying to make this argument that this is already a thing. We have this implicit narrative structure in the mechanics and level design, but the job of criticism here is to help designers see that as an important thing that they’re already doing but don’t understand they’re doing. [I’m hoping to] give them some language so games in the future can more clearly see the importance of that implicit narrative structure and tie it to an explicit narrative structure.

Tone Madison: That’s great. I’m also thinking of and curious about the demographics of who’s playing games and how they’re perceived.

Peter McDonald: It’s always a little tricky to know—there’s a lot of assumptions about who’s playing games that are not true. Like, the demographics of who plays games is older and older and diverse in terms of gender and race. And a lot of that information is proprietary, and companies don’t share it clearly in ways that would make it easy to make direct claims about who plays platforming games. It’s complicated, because who plays platforming games in different sub-areas of the field is quite different. In the indie game space, there’s a tradition of queer platformers that doesn’t really translate into—there’s an argument to be made that Nintendo’s platforming games are all kinda queer in some way, but there’s a more direct, explicit queerness in the indie game scene of platformers.

Tone Madison: Queer in the old definition of the world, being “off-kilter” or “weird?”

Peter McDonald: You mean Nintendo’s ones?

Tone Madison: Yeah, the world itself is not a parallel or mimicking something that we see in reality.

Peter McDonald: Or even Super Mario Wonder, right?

Tone Madison: But when you’re talking about queer platforming, I was thinking more of like Celeste or something like that, which is different.

Peter McDonald: Exactly. But with Super Mario Wonder, it’s not just weird; the whole structure of that game is that every level of that game sets up a new norm, a new rule of gameplay. Then, halfway through the level, breaks it. So it’s all about this process of “norming” and de-norming.” I would make an argument that there’s something queer in that game in the sense of queer theory. But Nintendo might not acknowledge that.

Tone Madison: Ha, yeah, I can see that. Loren Schmidt’s Strawberry Cubes gets a prominent placement in Run And Jump‘s later sections, when you discuss metalanguage. You write, “By incorporating metalanguage of design and construction into basic pleasures, platforming games foreshadow the most dramatic shifts and the most transformative subversions that designers can imagine.” That’s really interesting. Then, is it safe to say that postmodernism, which also defined past eras of literature and film, is the future of the life of 2D platforming?

Well, Undertale exists, which is very meta, but that’s not a platformer. That’s kind of in the same realm.

Peter McDonald: If you haven’t taken a look, Loren Schmidt’s game is amazing. It gets into the same glitch aesthetic as Undertale. I think there’s something postmodern here, and is part of why I like going back to structuralism and post-structuralism, to me, makes some sense for this genre in particular. Some of the tools that we develop as humanists to understand the transformations that were happening in the ’60s and ’70s in film and architecture and visual art translate to the contemporary moment in platformers.

Tone Madison: Is there another game like Strawberry Cubes? I’m trying to think of something else you reference in here in the final chapter, before the postscript.

Peter McDonald: I mention a few folks in the introduction. There’s kind of two strands of contemporary indie platformers. One, which is trying to do something serious with the genre. I think Rain World is a good example of this, or Braid, or these games that are trying to use these mechanics to tell a story that’s important to the author.

Then, there’s another group of people who are messing with the genre in one way or another. Deconstructing it, breaking it, making it messy and glitchy. And so the queer artists are often at the core of that second strand. Anna Anthropy is another person who I’d absolutely recommend. She has a few games, including Mighty Jill Off. A sub-dom relationship is the core of the game. [laughs]

Another great one is [Madison-based] Terra Lauterbach’s SuteF, which is a game where if you fall off one side of the screen, it loops you back onto the other. Every time it does that, all sorts of weird stuff happens that disrupts your play experience. In general, there’s a lot of people making games on itch.io—a free platform for sharing indie games—who are doing weird stuff with the genre. Another one I love is called Windowframe, where you’re a vampire hunter throwing stakes. If you hit one of the sides of the game window, it freezes in place, and the rest of the window resizes around your character. So it’s this meta moment of the game window itself becoming part of your game experience.

There’s a whole bunch of experimentation happening, because it’s relatively easy to make these games these days with the variety of independent tools out there.

Tone Madison: It sounds like you’re optimistic about the ease of creation and distribution.

Peter McDonald: Absolutely. I’m constantly surprised. This is a genre that’s been around for 40 years, and people keep making new things every year that take it in a new direction. You’d think, after this much time making these games, there wouldn’t be a lot of space left to explore, I don’t think it’s running out of steam any time soon.

Tone Madison: Since I’ve referenced cinema a bit, especially because I write about movies and watch so many of them, I wanted to know your thoughts on Indie Game: The Movie (2012). Was that documentary—about the making of Fez and Super Meat Boy, and reception of Braid—influential in your studies when it came out over a decade ago? If it was or wasn’t, do you think we’re overdue for a spiritual sequel or new video-game doc that explores the soul and inner-workings of creators?

Peter McDonald: I have some problems. I feel like Indie Game: The Movie focuses on a couple specific kinds of narratives: White men who love Mario and have this nostalgia driving them to make it or break it in the industry. I think there were a lot of other interesting people who had different kinds of stories making stuff at that moment in history. As a movie, I’m really glad it exists, and I wish there was more from that era that told other peoples’ stories as well.

And absolutely, I agree that we need more of this in the present. I think it’s kind of an unfortunate side effect of game companies being really protective of their internal workings and putting everybody under non-disclosure agreements. It’s really hard to get documentaries like that made about things made by more than one person at a time. But it’s a fascinating internal process, and I really think that there’s a lot of interesting creative work that people would enjoy seeing.

The one example of the most interesting thing I’ve seen lately is there’s a playable documentary that just came out on [the making of] Karateka, which is an early platforming game. And it’s a program that includes a lot of film footage, playable demos of early things. It’s an interesting way forward for this kind of documentary. One of the difficult things in translating video games to film is that you don’t necessarily get a sense of what it’s like to play these things, right? To hold the controller and experience the tactile dimension.

Tone Madison: They do get into that in Indie Game: The Movie a bit. There’s a key scene where the developers of Super Meat Boy talk about how to have the character feel with movement and jumping. So that’s kind of integral.

Peter McDonald: When you have this hybrid form of video game documentary, you as the person watching it can play different versions of what the character felt like at different moments [during development].

Tone Madison: That’s really cool, kind of the next evolution—well, it’s not even that. It’s something else entirely. But sort of building on what was presented in Indie Game: The Movie, as I mentioned. Are there other feature films about game development that had as high a profile as that?

Peter McDonald: I haven’t seen anything that’s anywhere close to that. There are some documentaries—one about Tim Schafer at Double Fine [called Psychodyssey], and it’s great.

Tone Madison: Oh, yeah. “Day of the Devs” guy. It’s almost like “Day of the Devs,” which is part of Summer Games Fest, is its own anthology documentary. Because you’re seeing people talk about their games, and it’s being presented in a similar way. But it’s more promotional, obviously.

Are you yourself developing or working with anyone on a game? Or, if you can’t say, do you have future plans to write more on the philosophy of gaming? Maybe expanding to the boundary-disrupting 3D games that you briefly discuss in your introductory chapter?

Peter McDonald: I make a variety of kinds of games. I used to make a lot more of these things called alternate-reality games, which are large-scale, in-person games that don’t tell you they’re a game. If you’ve never seen The Game [with Michael Douglas], I recommend seeing it. These games are like: You might get a record in the mail, and you don’t know why it’s there or who sent it. If you listen to the record, there’s a code that directs you to a certain date and place where you’re supposed to show up. If you decode it, show up, you’re playing the game. And it goes on all sorts of trails after that. The pandemic put a little [kink] in making these things for me, so I’ve been working on some tabletop role-playing stuff lately.

In terms of future research projects, you can look forward to another book coming out [The Impossible Reversal And Other Styles Of Play, scheduled for a 2025 release], on that larger question of the history of playing games in American culture and the art movements in the ’50s and ’60s. After that, we’ll see. I have lots of thoughts about new big projects to take on, but not sure what the next one is. I would really like to do some ethnographic work inside a video game studio, speaking of the kind of documentary side of things. I’m hoping to get a couple grad students to do three days a week, sitting in with some indie studios, and some educational game studios, to think and write about what those internal processes look like. But that’s still kinda blue-sky.

Tone Madison: Locally?

Peter McDonald: Yeah, in our [university] area here there’s Field Day, which partners with PBS and does educational games through government grants. There’s Filament Games in Madison, which also makes educational games, but [is] a for-profit studio. And I know some people, from when I was in Chicago, who do independent game development.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.