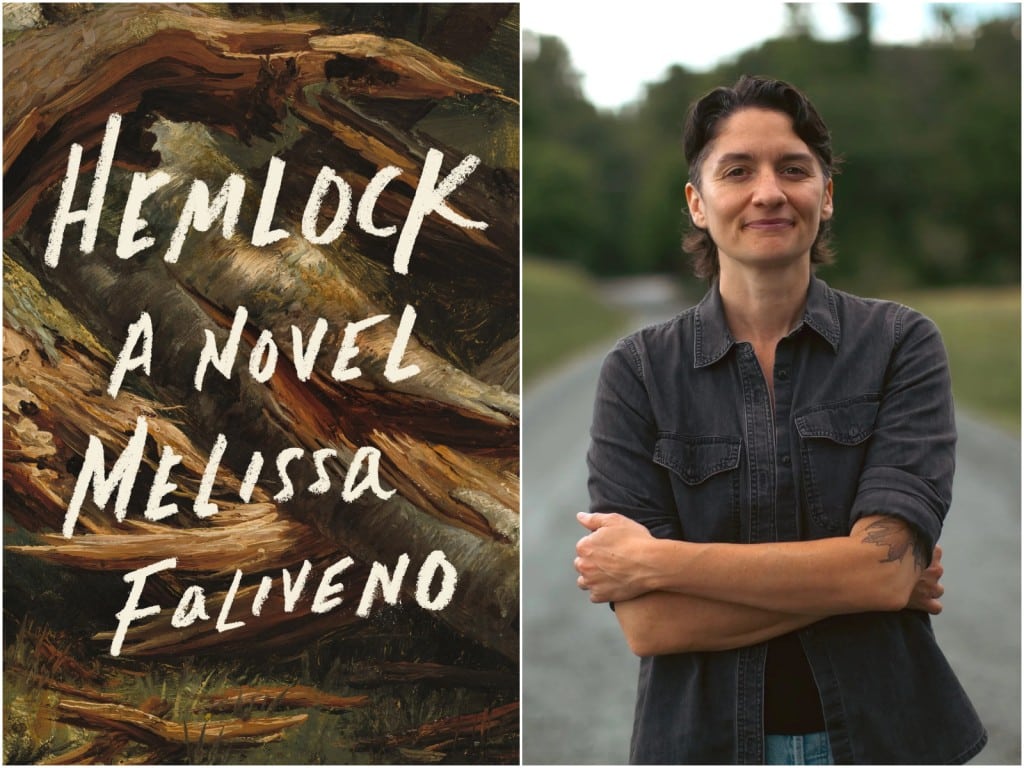

Fear and queer hunger in the Northwoods of Melissa Faliveno’s “Hemlock”

The new novel from the author of the “Tomboyland” essay collection finds its footing in the dark corners of Wisconsin’s forests.

It’s deeply fitting that Hemlock, the forthcoming novel from author Melissa Faliveno, opens with a quote from beloved queer writer Leslie Feinberg from their book, Stone Butch Blues: “Nature held me close and seemed to find no fault with me.”

The quote is one that has particularly resonated with me and likely countless other people who have found comfort and acceptance in the natural world, particularly when the human one didn’t offer it. For Faliveno, a native of Mt. Horeb (and former Madisonian) who has since called everywhere from New York City to Ohio to (currently) North Carolina home, the quote became a sort of guiding star for writing the book.

Faliveno is most well-known for their debut essay collection, Tomboyland, which was named a Best Book of 2020 by NPR, New York Public Library, Oprah Magazine, Electric Literature, and Debutiful, and was the recipient of a 2021 Award for Outstanding Literary Achievement from the Wisconsin Library Association. All of that made it somewhat surprising when I heard that her next offering would be a novel and not another memoir or essay collection.

When I asked Faliveno, currently an assistant professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, about that change of course in an interview over Zoom in November, she laughed. “It’s a question I’ve been asking myself for a while,” she said. “The truth is that it was less of a decision and more that it just kind of happened.”

Hemlock, indeed, feels like the kind of writing that bubbles up, unbidden, from deep within. The novel is an intensely felt and very queered exploration of personal identity, inherited trauma, desire, and relationship with place. Set in Wisconsin’s Northwoods, there’s a lot to love (and, for locals, to recognize) in Faliveno’s evocative descriptions of the titular cabin, other people in the small nearby community, the forest that surrounds and sustains them.

We talked about the use of setting as a character, the particulars of Midwestern/Northwoods Gothic as a genre, queer bodies in rural spaces, and the sweetness and pain of loving a place that doesn’t always love you back—among many other things—over the course of our conversation.

Hemlock will publish on January 20, 2026, with Little, Brown and Company. Faliveno will read from and talk about the book at A Room of One’s Own in Madison on Thursday, February 19, at 6 p.m.

(The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.)

Tone Madison: What was the motivation for writing this particular book? What did that journey look like for you?

Melissa Faliveno: On the one hand, I think that I needed a little bit of a break [after Tomboyland] from writing about myself, but then the hilarious irony is that with this novel, there’s a lot of me in it. And this character is not me, but is sort of a shadow self, you know?

When I started writing, I thought it was going to be an essay about the time I spent up at a cabin in the Chequamegon Nicolet National Forest, when I was finishing Tomboyland. I was there alone for six weeks, and it was the most alone I had ever been. I’d come there from New York and the silence was deafening. It was frightening at night in a way that I had never really experienced before. So I was very much alone and very much in my head, and I started writing this essay about the experience.

That ended up becoming an essay that was published, but when I got back to New York, I had this whole summer stretching out before me. I had quit my job and I needed a project. The best advice I got was that, as your first book goes into publication, make sure you have a project. And so I did Jami Attenberg’s “1000 Words of Summer” when Twitter was still Twitter and there was a fun writer’s community there to support each other. I started writing 1,000 words a day, not knowing what I was doing really, and suddenly this story started to unfold. I literally had no designs on it ever seeing the light of day. It was just having fun writing. That was super important because I was also overcome with anxiety about my first book being about to come out. From there, it just kept growing and suddenly I had a first draft, and I thought, holy shit! I wonder if this is something.

I kept working on it and revising until spring of 2021 when I finally had a draft that I thought was good enough to send to my agent. I went to her and was like, “This is probably nothing, no pressure, I’ve got an idea for my next essay collection so we can just pretend like this never happened.” [laughs]

But she said, “This is great!” She gave me the green light. We spent the next several years working on revisions.

Tone Madison: I’d be curious to get your thoughts on the place of fiction versus nonfiction when it comes to exploring similar, personal themes and questions. You talked about how the main character of Hemlock is a sort of “shadow self,” for instance. What role do you think fiction plays versus. an essay? How are they complementary or different? Where do you think fiction works better to dig into some of those themes and questions, or where is non-fiction maybe more effective?

Melissa Faliveno: I’m actually—surprise, surprise—working on an essay about it right now, because it’s this question that I’ve been thinking about, and [writing essays] is how I answer it.

What has become clear to me is that there were certain things that I felt like I could not write an essay about. With Tomboyland, for example, there were stories that I ended up cutting late in the game. I had this sort of crisis where I realized that some of these stories were just not entirely mine to tell.

I also couldn’t tell them fully without these other aspects, one example being my and my family’s relationship to alcohol, the Wisconsinite relationship to alcohol. It’s this thing I’ve thought about for a very long time and have struggled with, but had never fully questioned whether or not I had a problem with alcohol. Even when I started writing this book, I didn’t think that I did. And the book became this way of interrogating my own relationship with alcohol, and ideas of inheritance and growing up in a place that is so culturally defined by drinking.

Fiction felt like a place that I could explore that really deeply, and include ideas of inheritance and familial problems with dependency and alcoholism that I’ve been thinking about for a very long time, but it felt more approachable to do this work outside of the context of my own family.

In terms of themes around gender, it also really felt like a good way to explore my own very quickly evolving relationship with my own gender identity. Even from when I was writing Tomboyland to when I was writing Hemlock, that changed, as it does. It’s very fluid.

So I was like, what if this is a transformation novel, and it’s an addiction novel, and these are the two things that I am thinking about on really deep levels, and don’t quite feel like I can write fully in nonfiction? Maybe because they’re not fully mine to tell, maybe because I’m still really figuring it out. I felt a lot of freedom in exploring these two ideas and questions beyond the parameters of my own life.

There’s a lot of myself in there, and there’s a lot of my family in there, but it’s also fiction, and I had this experience where, as I sat back after writing it, I was like, “Oh, in some ways this feels more true than some of the essays I wrote in Tomboyland.”

Tone Madison: Was there anything about the process or what came out in the book that surprised you?

Melissa Faliveno: Yeah, absolutely. In the thread of addiction, mostly, that was where the most revelation happened. And I wrote this whole thread in the novel about a character who has a bit of a death drive, and a kind of call to oblivion, a desire to destroy herself. Every time she cracked a beer there was this potential of that call to oblivion.

I guess it’s hilarious how I didn’t quite see this when I was first drafting the novel, and it took until draft two or three before I sat back and looked at that section and realized, that’s totally me. That’s totally the voice that I have heard my whole life. I was writing the litany of things that Sam had experienced and I realized I was drawing almost entirely directly from my own life. Seeing them all on the page together made me realize that the story is more mine than I thought. There’s more of me in Sam than I originally believed.

It was a kind of series of revelations to the point that I realized her relationship with alcohol—which, when I started writing the book, felt very different from mine—by the time I got deep into revisions, I could see that they’re not actually that different. The shape looks a little different, but there it is.

That was a pretty huge surprise and a huge revelation. That’s when I thought it was maybe time for me to stop drinking.

Tone Madison: That is huge.

Melissa Faliveno: Yeah, and then all these other things happened, too. I lost a former partner and a very close friend of mine, in no small part, to alcoholism and suicide. His narrative was very wrapped up in this, too. I had this confluence of experiences that left me staring at what I had written and thinking, this is kind of like an omen, you know? There’s a potential future here if I, like Sam, step into the woods.

Tone Madison: I like to talk a lot about how sometimes there’s pushback against being “hyper-specific” or niche in our writing, especially as people from marginalized communities. With Sam, we’re talking about a queer, androgynous character. It’s not exactly a mainstream narrative. But when we get down to it, the more supposedly “universal” stories we’re fed often feel very bland and hollow. Whereas, the more specific you get, really telling a personal story, it feels like that’s what makes it more relatable and, ultimately, more universal. Even if it’s not someone’s exact story, the themes within it tend to be much more relatable.

I’d love for you to talk about the queerness that runs through the book. There is, unfortunately, a very strong tie between queerness and queer experience, and addiction and mental health issues—not because we are queer, but because we’re raised in a world that doesn’t treat us very well, so we often turn to various, unhealthy coping mechanisms that are most available to us. We see that play out in the book, which takes a very moody, atmospheric, and psychological approach to storytelling, versus being very action/plot-driven. Why did you choose to do more of a character study, where you can’t always tell what’s real and what’s not? And why was it important to focus on queerness—in terms of identity, sexuality, place, all of it?

Side note: thank you so much for putting an actual sex scene in there. I was really worried it wasn’t gonna happen. I’m so used to being teased and then left wanting, especially when it comes to queer relationships.

Melissa Faliveno: We get so few!

Tone Madison: Truly! I was raised on crumbs.

Melissa Faliveno: I was like, listen, I’m gonna write this section. I had never written what I felt like was a successful sex scene before and I was really nervous about it. But I wanted it there! So much of this book, for me, is about desire, and a character who doesn’t even understand their own desires. She goes back to this place that made her, that raised her, and is grappling with all of these desires that maybe have been silenced, or repressed, or not interrogated.

Sexuality and gender and addiction are all wrapped up in this desire for a sense of selfhood and a sexual desire, too. It’s this sort of ravenousness that she hasn’t experienced before, or allowed herself to experience.

I wanted that to really be wrapped up with this hunger or thirst, this sort of insatiable appetite, both carnally and for everything else.

It was really important to me that this character’s sexuality and gender identity be very fundamental to her story, in ways both physical and mental. And that, in returning to this wild place, she’s able to access these parts of herself that she hasn’t been able to access in New York, or in this life she sort of forced herself to perform that she was never comfortable performing.

There’s also freedom, so her body is changing shape, her desires are becoming much louder, and the trappings of society are sort of sloughing off. She’s becoming feral, you know?

Tone Madison: Big wendigo energy here.

Melissa Faliveno: Yes, exactly. There’s this creature of appetite who’s roaming the dark woods, right? I was talking to another friend who’s an author who also wrote a queer book about a person who’s living alone and becoming feral, and we’re like, “Okay, we’re writing the feral queers in the woods canon, finally.” [Laughs]

Tone Madison: Extremely relatable, I love it. Let’s talk about the woods, then, specifically the Northwoods as the setting and a major motif in the book. What drew you there, specifically? The Northwoods, and rural spaces generally, are not always the most friendly places to be queer. And yet, your character is still finding this freedom and this space in nature. It’s a tension that I think a lot of queer folks from or with ties to rural places have, that we might love nature and we love those places, but we are not always welcome there by the other people who’ve staked their claim there. So why come back to Wisconsin, to the Northwoods, and make it so central to this story?

Melissa Faliveno: Yeah, I love that question. I feel like it’s really important to all of my writing, much like Tomboyland, which was very much about that very tension. Wisconsin is this place I feel very connected to, and it still feels like home to me, even though I’ve been gone for 16 years. And sometimes I return, and I’m like, oof. I don’t feel awesome here, you know? And including that time that I was living alone in the Northwoods, working on Tomboyland, and wearing this very queer body and driving 15 miles into town to go to the grocery store or the gas station, or to use the Wi-Fi at the library… I did all these things and I was made very, very aware of my body in this place, coming from New York, where I rarely felt so aware of my body, where I just felt like I could blend in very seamlessly to my life and my community and my neighborhood in Brooklyn. Suddenly I just felt very visible. So there was this weird, very complex contradiction, where I felt like I was home, and I felt really uncomfortable.

That tension, I think, drives a lot of my writing, that the places I feel best in are often the places that don’t like queer people. Places where my body and our bodies feel very visible in ways that we don’t always want to be.

The Northwoods, to me, are just this place that I spent so much time in when I was a kid. I went there all the time, several times a year with my family, who still have a cabin up there. It was this elemental part of my youth, walking in those woods, swimming in those lakes. It felt like a slant home for me. I didn’t grow up there, but I grew up going there, and so when I went back and stayed on my own for so long again, I felt, at once, both of this place and not a part of this place. If that makes sense? And that was the feeling I really wanted to dig into.

There’s a scene where someone asks Sam where she’s from, and there’s this whole meditation on what home is. This idea of the city—to this woman in the grocery store in the Northwoods, Madison is the big city. There’s a lot of city versus rural, and this idea of leaving a city and returning to rural space, but having that very conflicted feeling of home, which I think is true for a lot of queer people. Sometimes it’s very difficult for me to be in the place that I call home. Maybe it’s true of everywhere we “go home,” or everywhere we go. I certainly feel it in North Carolina. I think it’s an idea I’ll be grappling with for the rest of my time as a writer, because I will continue to inhabit this queer body in whatever space I’m in. What are the corners of this place where I feel good, and what are the corners of this place where I don’t? How can I build a sense of home and self here that feels whole and good and true?

I tell my students all the time, when they say they feel like they’re writing about the same thing over and over; it’s about finding different forms and different lenses through which to examine the same things, whatever obsesses us or preoccupies us.

Tone Madison: This book, this story, and many of your essays, they always feel like bittersweet love letters to these places that you want to love you more, and just don’t. And yet we still love them, for better or for worse.

Melissa Faliveno: Yes, exactly that.

Tone Madison: Let’s talk about genre and tone. The book definitely has elements of the Gothic, but I admit I’m more familiar with Southern Gothic as a genre, like Flannery O’Connor. I love this idea of a Northwoods Gothic, though, and would be curious what you think specifically that means? What are some of the influences you brought into it?

Melissa Faliveno: Yeah, totally. My interest in the Gothic goes back, I think, to 2010. I had recently moved to New York. I found myself writing about Wisconsin, because I was homesick. I went to AWP one year and discovered this literary magazine at the conference’s book fair, called Midwestern Gothic. I picked up a copy and I was like, “Oh my god, this is so cool.” And I talked to the editors, and decided then and there that I would write something that they’d publish.

A few years later, I did, and that was “Driftless,” one of the essays that would later be included in Tomboyland. When I was writing it, though, I didn’t think of it as being Gothic in any way. It’s very pastoral, but there’s also an element of darkness and the land being both lush and alive but also kind of brutal. This is how I think of so many Wisconsin and Midwestern landscapes: fertile and beautiful and unique, but also devastatingly cruel sometimes. I’ve been thinking about this idea of the Midwestern Gothic ever since then.

When I started writing Hemlock, I wasn’t necessarily thinking about that, though. It was just this weird interior, character-driven something that clearly has speculative elements. It’s, in many ways, an homage to horror.

It really wasn’t until I sold the book or was working on revisions with my agents that someone else used the word and I thought, right, yes. When I look back retroactively and think about this idea of it being a Midwestern Gothic, I’m thinking about what makes it that, or even more specifically, what is a Northwoods Gothic? What does that look like? How does the land and the landscape become a character? Where do these elements of the supernatural fit in? I thought a lot about folklore and the wonderfully rich tradition of these forest monsters. We’ve got so many folktales of creatures that live in the woods, across so many cultures. Everyone is both reverent and terrified of what exists in the woods. And that, to me, feels very Northwoods Gothic. Revere whatever is in there, because it’s the beating heart of this land. These untouched spaces, we have a healthy fear of them, which is like, in many traditions, one’s relationship to God, this kind of reverence and fear.

I think that that was where a lot of the Gothic feel came from; what lives in the woods, and what might be haunting the woods? That’s a big driver of this book, the idea of hauntings and a person being haunted, a place being haunted.

Tone Madison: “Haunted” really feels like the right word for so much of what’s going on in the book, both on the spiritual or supernatural side of things, but also very tangibly within the character and her family’s history. Sam comes from people who worked themselves, sometimes literally to death, in factories that have since shut down. No one really got to retire and enjoy the fruits of their labors, which is the very real legacy of the boom and bust of industry and capitalism in the Upper Midwest. The reverberations of that cycle are still felt through the generations, the shuttered downtowns, and so on. You have a character who’s Indigenous and talks a bit about that much larger history of displacement, of essentially an apocalypse, and how all those things are at a sort of crossroads meeting in this haunted place.

Melissa Faliveno: That was hugely important, too. These Northwoods towns, a lot of the ones I grew up going to, were such tourist destinations in the ’80s and ’90s, and just booming. It’s not as bad now in some places as it was, but I have this image in my head of a place that used to be crawling with tourists but now is just kind of a creepy-looking ghost town. Especially after 2008, just seeing these landscapes change, these towns change in that way, I really wanted to show a town [in Hemlock] that had been affected in this way. It’s a really big part, like you say, of the Midwestern experience.

Tone Madison: I recently read about a study of the words used in English language books over the last 100 years or so, and it showed a significant decline in the number of nature-based words used, especially in recent years. Our world is so much more shaped by technology and overall having less and less connection to the natural world. It’s less of a character in our lives. That’s part of why I was so delighted at what a large role the natural world plays in this book and in the language you use. Even when it’s creepy or frightening! What is your relationship with nature, and how or why did you look to incorporate nature as a central character–not just a setting–in this story?

Melissa Faliveno: A couple things came to mind as you were asking that question. One was this quote that I used as an epigraph for the book that has been in my mind since I read it, which is from “Stone Butch Blues” by Leslie Feinberg. The quote is, “Nature held me close and seemed to find no fault with me.”

Which, by the way, Leslie Feinberg famously did not want most of their work repurposed in any way. I spent a ton of time trying to see if I could get permission to use this quote, and their estate finally got back to me and said they thought it seemed like the perfect kind of book that Leslie would want their words associated with. At which point I was like, “OK, I can die now.”

Tone Madison: Holy shit, yes. That’s… I mean, I think so, and I agree, but gosh, that’s gotta feel so validating to get from the estate.

Melissa Faliveno: Very much so. I read that book kind of late, you know. It was when I moved to Ohio, around 2021. And it just blew my mind. I mourned the fact that I hadn’t read it earlier in my life, and I was so grateful to have found it at the exact moment I needed it. I have had that quote in my head since then, and it became this kind of torch for writing this book.

Going back to this idea of finding yourself in this place that raised you, even though there’s also an undercurrent of fear that runs through it, this threat, there’s also a sense of home and safety. There’s this sense of, “I’ve never felt safer than when I’m being held in these trees.”

That was the image that propelled the entire book, I think. It’s so true of me, too. Walking in the woods is my favorite thing to do, and I don’t do it enough, and every time I do it, I’m like, why don’t I do this literally every day of my life? Because it’s the place I feel best.

And to your point about the language we use, I think it’s really interesting because that, too, is a thread I had a lot of fun with while writing this book. How words can have multiple meanings, how places have particular dialects, how they talk about and think about things. The most obvious example is “hemlock” itself, which is both the name of the cabin in the story and most people associate it with the name of a poison plant. But it’s also this endangered species of pine. Currently, in the United States, the eastern hemlock is making this slow death march across the country. It’s only threatened in Wisconsin, but that will almost certainly change. So the hemlock tree being this metaphor for Sam and for the land, for everything that’s threatened and endangered, was very intentional.

I was also thinking about this word “pharmakon,” which means both poison and remedy, when I was thinking about alcohol as both a thing that people use to make themselves feel better, but that can also destroy us. It all felt interconnected.

I’m always interested in the language of place and what it says about the communities there, how we keep that language alive in those places, and how the mythologies and narratives of a place are kept alive through that language.

Tone Madison: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me about all of this. I hope the holiday season treats you gently.

Melissa Faliveno: You’re so welcome! Thank you for being interested. I hope we all get to spend more time walking in the woods, even in the winter.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.