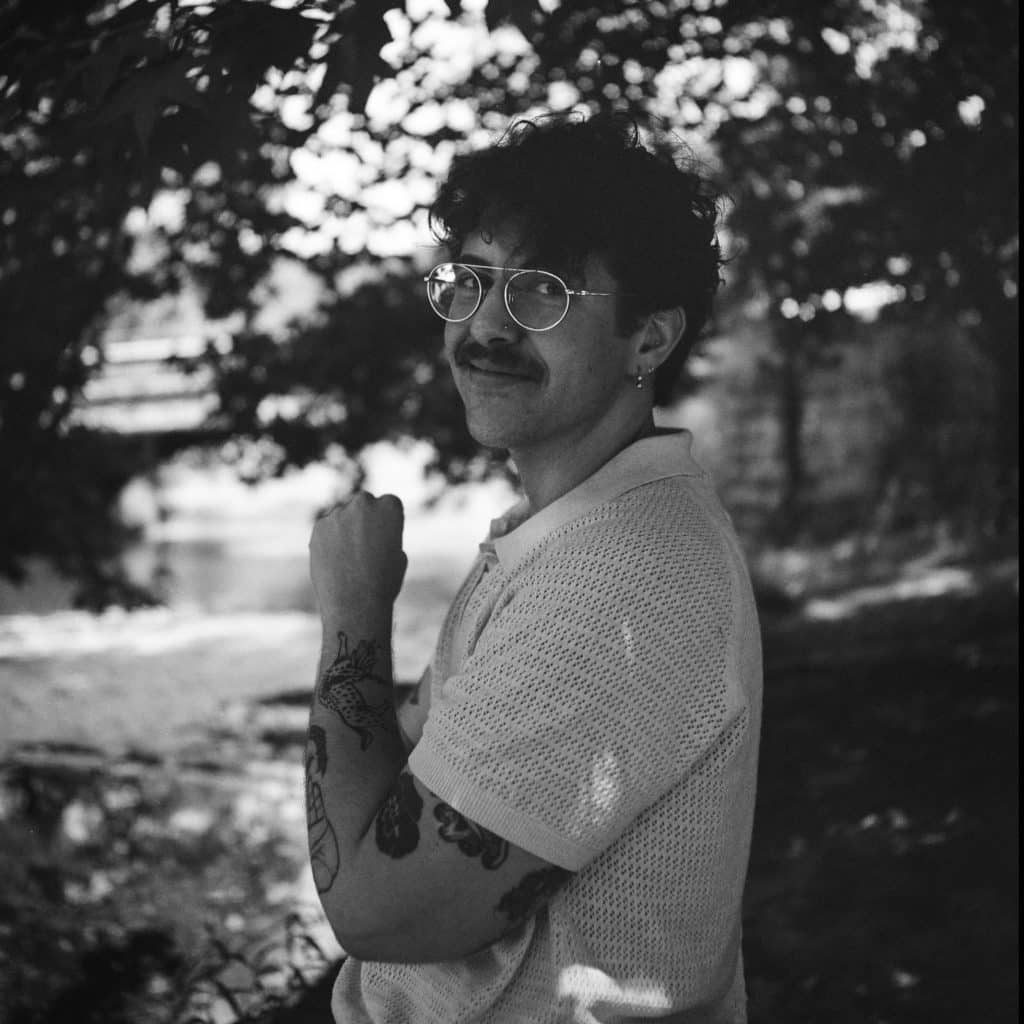

Family histories and contemporary violence collide in Solomon Brager’s “Heavyweight”

Brager will discuss their debut graphic novel on April 10 at the Central Library.

Brager will discuss their debut graphic novel on April 10 at the Central Library.

Heavyweight is Solomon Brager’s debut graphic novel about their family’s escape from Nazi Germany during the Holocaust and immigration to the United States. Brager’s great-grandfather, Erich Levi, a heavyweight boxing champion, and their great-grandmother, Gertrude Ilse Kahn, fled rising fascism and antisemitism in Europe during the 1930s and ’40s, eventually settling in New York, on stolen land. Brager explores themes of intergenerational trauma, and the intricacies of colonialism and imperialism that shape immigrant narratives of resistance, persecution, and assimilation.

As Brager researches their great-grandmother’s history, they uncover her privileged upbringing in Germany as the result of a lucrative family oil business. She had money in the bank to pay for her immigration out of Germany and across Europe. Brager asks how this wealth protected her as she was forced to live life on the run from Nazis and Nazi sympathizers in Belgium, France, and Portugal. At every corner, Kahn risked being turned into the police, who could then hand Brager’s family over to the German government. Levi was not so lucky; he was captured by Belgian police, and spent time in a French internment camp.

I couldn’t help but think about parallels between Brager’s family story and rising facism today. The Nazis blamed Jewish people, immigrants, and other marginalized people for Germany’s economic downfall in the aftermath of World War One. The United States and Israel carry out Palestinian genocide, state violence, censorship, and deportations today in the name of Jewish safety.

Brager asks readers to contend with these contradictions: that Jewish people, in particular, can both be victims of persecution and complicit in ongoing colonial violence.

I sat down with Brager in late March and asked them about what they hope readers take away from their graphic novel, how they managed to uncover pieces of their buried family history, and their process for writing a graphic novel for the first time.

Brager will be giving a presentation with Erika Meitner at 7 p.m. on Thursday, April 10, at the Central Library in community rooms 301 and 302, presented by the Wisconsin Book Festival.

Tone Madison: In Heavyweight you talk about these seemingly contradictory narratives; first, that your relatives were both victims fleeing persecution while also benefiting off of stolen land and wealth as a result of imperialism. Something that really stuck out to me was, at one point you said, “I need you to understand that we can both be victimized and complicit in violence.” And when I was reading, that sort of felt like the thesis of your work. What would you characterize as the thesis of your work or what are you hoping that readers take away from it?

Solomon Brager: Yeah, I think that’s definitely, if not the thesis statement, definitely part of the framing thesis of the work. You know, the idea that really animates Heavyweight is to take this central story of my great-grandparents escape from Nazi Germany and their experience under Nazi occupation, which, for them, basically constituted the period from 1933 until they escaped in 1940 and then from a distance until, obviously, the end of the war in 1945, right? So in the length of the life of someone like my great-grandmother, who lived into her 90s, that’s not a very long period of time in which she’s being directly targeted or victimized by violence.

So when we talk about the Holocaust—because I have worked as a Holocaust educator, because I grew up in a Jewish community–we’re always talking about those years, and my question to the readers is, what happens if you zoom out from those years… and think about the way that ideologies and and practices of violence, practices of colonization are basically structurally spread over an entire planet, right? That we’re not just these little discrete spaces at times. And so I think that when you zoom out, necessarily, the picture becomes more complicated. And so if I’m asking anything of the reader, it’s, can you sit with the messy, complicated story of the world, and can you then think about what your own place is in that story?… There’s another moment that’s probably in around the same part of the book, where I talk about the scaffolding of violence, and how everything is connected to everything else. And if the scaffolding doesn’t change, then the story isn’t going to change.

And so a thing that I hear back that is both terrifying and upsetting, and also means that I did a good job, is that people recognize the present in the book, recognize their own family stories from other places in the book… We didn’t actually successfully do a process of denazification—not in Germany, but also not anywhere. Those ideologies remain very, very much in place… And so, I do hope that there’s a little bit of an inspiration for you to be like, okay, what would it take to actually change any of these things, right? Which I don’t have the answer.

Tone Madison: I don’t have the answer either, but I definitely think about that a lot too. I mean, obviously, keep talking about it. I think a lot about how especially in Jewish communities, there’s a lot of denial to that, like Jews can’t be anything but victimized, and I think that hurts both our communities and the world.

Solomon Brager: Yeah, totally. I think you’re bringing up something that’s really important that’s tied back into that statement of both being a victim of violence and being complicit in violence. The way I really wanted people to read this book is think about the way that they have learned about and the ways they’re continuing to talk about the Holocaust, particularly in Jewish communities. The way that Holocaust education has been invested in in Jewish communities is as this kind of evergreen, ever-present kind of sacred event, like we’re all supposed to kind of still be living on the edge of. So that both makes it very hard to recognize, obviously, complicity and other violence, including the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and also the ways in which we as American Jews are complicit in all these many, many genocides that are always happening around us, and the demands of capitalism and the way that the United States has destabilized much of the planet, but also that makes it really hard to think about quote, unquote, lesser violences…within our own communities.

Tone Madison: You talk several times in your graphic novel about historical persecution leading to the weaponization of victimhood. How did you see that play out in your family narrative and in the present day?

Solomon Brager: We talked a little bit about the ways in which failure to examine the impact of one’s own victimization can snowball into other forms of bad behavior, including domestic violence. I’m not going to claim that my great-grandfather wouldn’t have beaten his son if he hadn’t been in an internment camp, but I don’t think it helped… But I do think that there is a very direct rhetorical weaponization of the victimization in the Holocaust in the present moment, right? The State of Israel, and then Jewish communities, particularly in the US, where there’s a kind of constant hammering of “the reason that what’s happening in Gaza needs to happen is to prevent another Holocaust,” when there are very, very strong arguments and a lot of evidence being made for this constituting the same violence in the same vein as the Holocaust.

So this kind of inability to recognize anything outside of one’s own experience is a pretty dark legacy of the Holocaust. And I think one of the points that I make in the book, and one of the things that you might have noticed:there’s these kind of, sainted figures of Holocaust literature. For example, an Elie Wiesel, who was a survivor of Auschwitz, who was an incredible writer, and in many ways a very thoughtful person, and also someone who was very unwilling to recognize the victimization of populations other than Jews in the Holocaust, which really led to an inability to see structures of harm have continued. There are populations that never stop being victimized by the Holocaust. Gay men remained in prison, disabled people continue to be targeted by eugenicist projects and being institutionalized and killed and neglected by actual targeted state killing. That was fine, because they’re, they’re still undesirable people, right? There wasn’t a real contention with that. But then also he [Elie Wiesel] felt very strongly that the only definitional thing that we can think about is the Holocaust, right? The Holocaust as a sacred event… the thing that all other historical events are compared to. He’s one of the people who helped produce that… And so he’s not in my book, right? I don’t even try to put him in to debunk him. I’m just like, what if we turn to these other legacies of writers?

And for me, the supreme writer of Holocaust experience should be Primo Levi. I think he’s the smartest, most interesting writer who is thinking about the Holocaust as a human event. He’s a supreme humanist. And he’s really like, how do we think about being humans in a world that could produce this kind of violence? And the questions that he’s asking, the way that he’s asking people to put themselves in, not only in the position of the victim, but also of the collaborator, as the person who is making decisions that feel impossible to us…

Tone Madison: In that vein, you were talking about some of the research you did, like reading Primo Levi. Can you tell me a little bit more about the research process and what that looked like? I’m especially interested in the process of uncovering the narratives of ancestors that you were not able to talk to directly. How did you get that information, if you weren’t able to either talk to them, or maybe narratives that your family members were giving you were incomplete, or just not there at all?

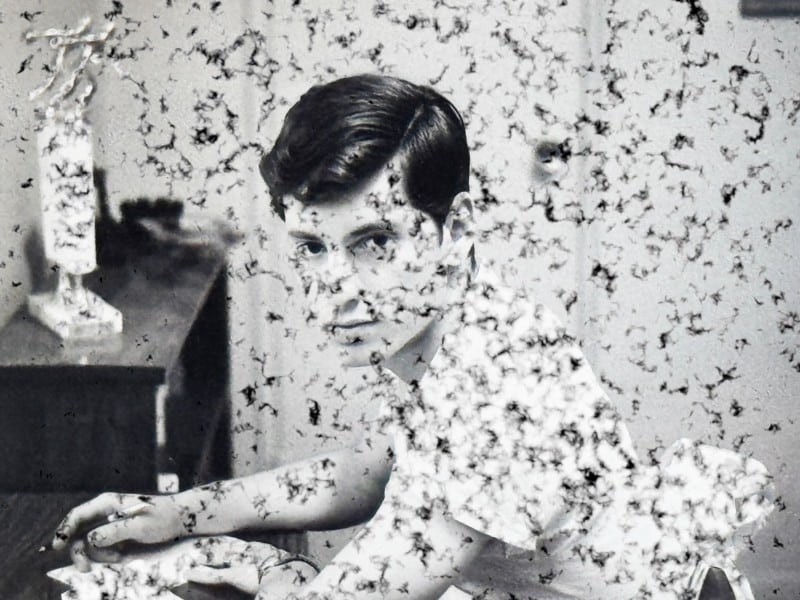

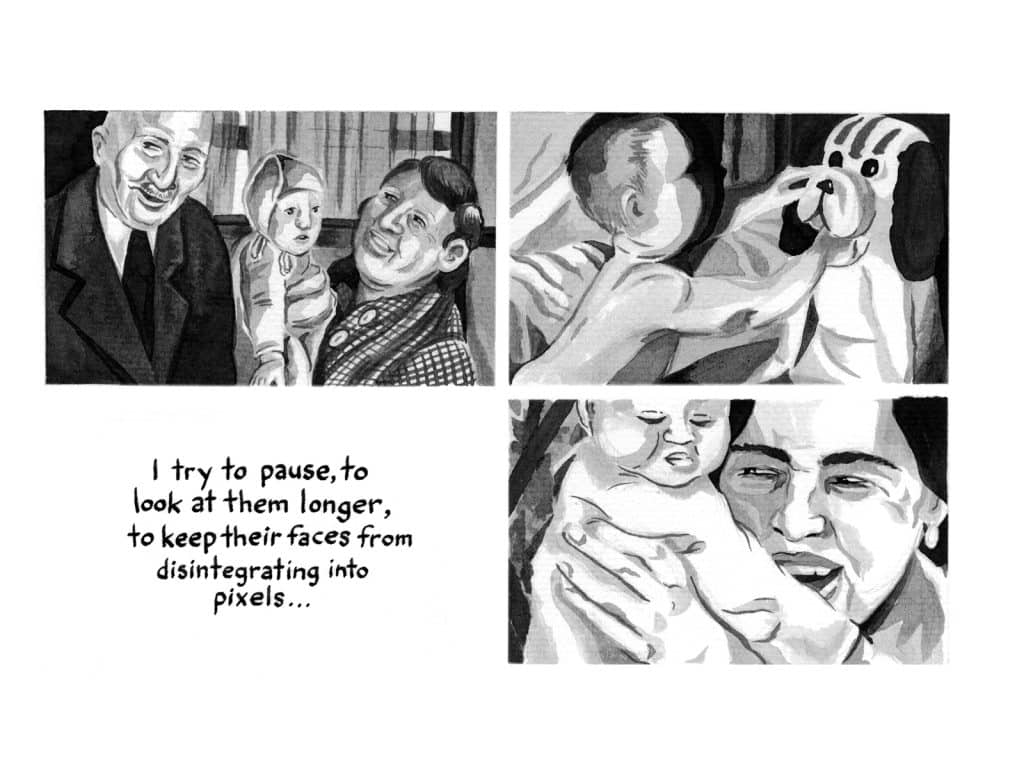

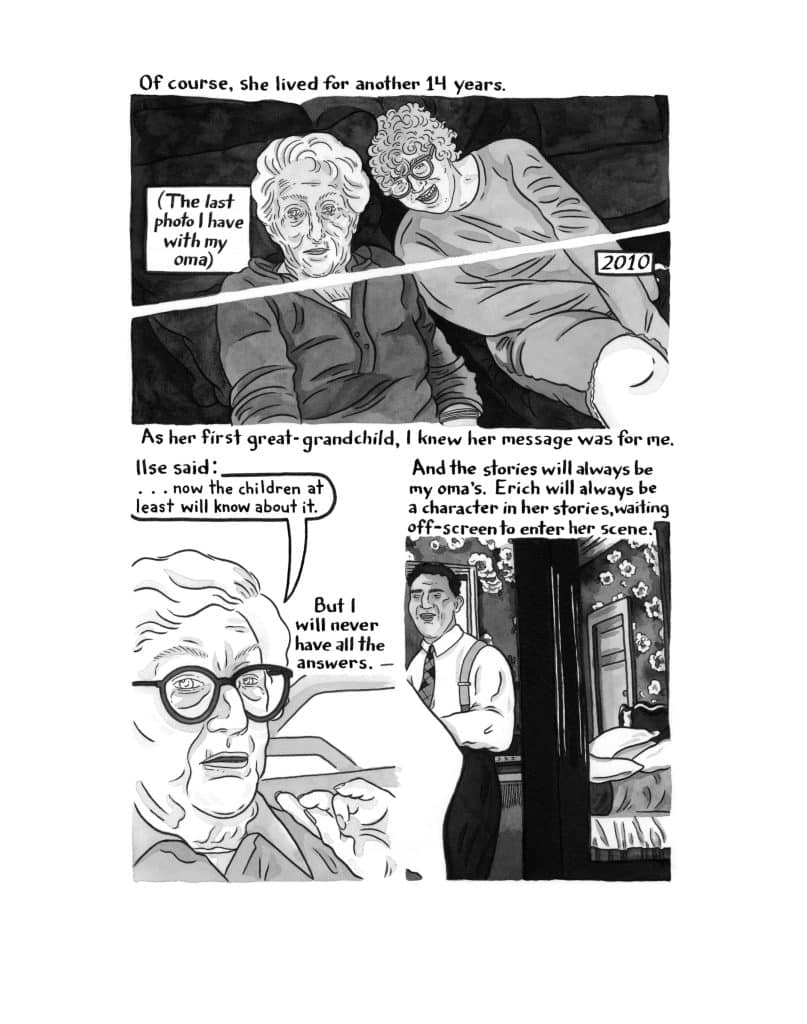

Solomon Brager: Totally. Actually, since I’m in my office, I’m gonna go off camera for one second to grab this giant Tupperware that I have, which may come back to bite me in the butt. So this is my research bin. [Sol grabs their bin.] For many years, my great-grandmother… would every so often do something like just mail me a loose photo. And I was like, What the hell are these? So she would sometimes send me a print, and then sometimes she would just mail me an original baby photo of my great-grandmother… And so I had these random images. And then my great-grandmother did a Shoah foundation interview in the 90s, and they made tape recording copies for everyone. So I [have] VHS tape of my great-grandmother talking, and I had used the VHS tape for a number of different projects… And I kept returning to it.

And then, as I got kind of more professionalized in academic and historical spaces, I did a fellowship at the Center for Jewish history. I had one with the Auschwitz Jewish Center, which is a partnership between the Museum of Jewish history in New York and this institution called the Auschwitz Jewish Center… And I was really studying the Holocaust, right? And I was thinking about where my great-grandmother’s story fit into these stories that I was writing about… And every so often I would just throw a place or a person’s name into a search and be like, maybe I can find something about my great-grandfather… who died in 1955, so I never met him, and, and he was this heavyweight boxing champion. Obviously. I was very interested in his story, but could never find anything. And I got to the point where I was kind of like, maybe the story is made up. Maybe he boxed a little bit, but wasn’t a big deal. Or maybe my great-grandmother is lying about some of this stuff…

The reality of that situation is like only a very small number of people’s stories make it into history books, obviously. And also the way that stuff gets into archives is, either a family donates it, right? Or an entire family is dead and stuff is recovered in some sort of spectacular way? So the place that most people’s stuff and most people’s family histories is in their basements and attics. I had to go talk to my family to find stuff… I went to their house, and their attic was just full of these crumbling albums… They just had all of this stuff that you would think would be in an archive. [Sol shows a picture of his grandfather featured in a newspaper for his boxing.] This is a clipping from my grandfather’s [boxing career]… They just had all this stuff. And the other thing that I got was a bunch more testimony from my great-grandmother that my aunt had done with her for a school project. She had tried to write her life story several times over the course of her life, starting in her 50s. She would like, start writing it out, and then just, as one does, set it aside and never go back to it over and over again. And all of these pieces had these little clues in them… As soon as you have another person’s name, it opens up all these additional doors?

And so one of the most incredible things that I found to me was that these cousins who did die in the Holocaust had these best friends who weren’t Jewish. And their family has, for the last half a century, been working to preserve the memory of their friends who died in the Holocaust city in Germany. And I just didn’t know any of this existed… But there’s a clear limit that is set by what a person has left behind in their lifetime, once they have passed away, right? … And my great-grandfather, really, left almost nothing behind… He didn’t record his experiences. He didn’t try to write about his life. And so, because he was of such interest to me as the other main character of my great-grandmother’s story, I was always trying to get at his experience, and always coming up short. For example, a lot of my great-grandmother’s testimony is about this period of time when they’re in Belgium, and Germany invades Belgium, and then they’re on the run for about a month, trying to get away from the Nazis and trying to get out of Europe. And during that entire period of time where she’s in a refugee camp here, driving around here, stuck in a bomb shelter there, he’s in an internment camp, and there’s no documentation of his experience in that time.

So there’s two things that you can do, right? You can look up other people’s experiences, which I did do. I was like, what was it like to be in this camp in France? And I could write about what people said about it, which was basically that it was like a pit of Hell, which is not surprising. And then you can do this process of historical fiction… And you know, there are a number of ways to do this. One is to write from a place of informed fiction, to sort of animate the ghost in different ways. Another is to write about the absence. And I think that a benefit of cartooning is that you really can get away with a lot.

Tone Madison: That’s so real. As a kid, I remember my grandfather brought up this big family tree. And I was like, I don’t want to learn about family history and everything, it’s boring! I was so reluctant, I didn’t actually look that deeply into stuff, but I remember seeing circles in the family tree with big x’s, and I asked, what happened? And my grandfather said they probably died in the Holocaust, but no one really knows much else. Because they’re just gone.

Solomon Brager: There’s a distant cousin who made a family tree, and they wrote, “KZ” which is the German designation for concentration camp death.

Tone Madison: What was the process like of actually creating your book? Not just the research process… but how did you actually put it together?

Solomon Brager: I had the really good fortune of selling Heavyweight on proposal. So when I sold it, I had a summary and a sort of historical timeline, and then [about] 25 pages of what I thought the book might look like, which I completely redid for the book. The longest comic that I had done up until that time was probably about 25 pages long. So I really had this moment where I was like, oh my god, this is incredible. I sold a book. I get to make a book. And then I was just seized with the total panic of how does one make a book? I started out trying to write a script in this program called Scrivener, and I was like, oh, I’ll submit a script, and then I’ll do thumbnails and classic editorial process, yeah. Very quickly, I threw that out the window.

Tone Madison: Yep, I know, I’ve been there. It’s comics! There’s images!

Solomon Brager: Totally. I was like, What am I gonna do, write out what I think the image will be? Ridiculous, right? So I actually did use an iPad for the thumbnail penciling process. And the benefit of working digitally, especially for pencils, is that I can move stuff around. So I was like, Oh, actually, this isn’t working here, so I’ll just pop it over there. And then also I got to a place where if I was drawing the same person 10 times on a page, I was just copying the person and then going in and changing their gesture or their expression… So what I ended up doing was rough pencils on the iPad, and then printing the whole thing out. And then, first of all, doing some of the editing on some of the printed off pages just to see what it would look like, but then also using a light box and paper over the digital pages. And so the final book is all inkwash and pen and ink on a very low grain watercolor paper. I decided not to use Bristol because I wanted to be able to layer more. And then we had to scan the whole book and do digital editing, and the whole thing is hand lettered, which is crazy.

Tone Madison: Oh my god, that’s not a font from your handwriting?! I’m just looking at it. The lines are so straight. That’s unreal.

Solomon Brager: Yeah, it was a pretty crazy choice. I don’t know if I’ll do it again, but at the time, that seemed like a great idea.

Tone Madison: How long did it take?

Solomon Brager: So I am a person who is very animated by deadlines. I believe in them, which I have since realized that literally no one else does. So I did not realize that the deadlines that I was given were a suggestion. So I sold the book at the beginning of 2021, and they gave me one year to finish it. And I was in a dead panic, basically. And I did not finish it. But I finished writing it in one year. I finished the pencils in one year, and then it took about a year and a half to ink it. But there were, in that time period, a bunch of delays. My publisher went on strike, for example, and my editor quit, so there was a lot of turnover and weirdness. But I worked at a pretty breakneck pace. That’s not something that I recommend to people. I was basically waking up, going to my drawing table, and then falling into bed at night. And I don’t think that that was good for my body or my creative process. People shouldn’t do that.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.