Evaluating tenderness and depth of family dynamics in “Sentimental Value”

Grant Phipps and Lance Li argue in favor of and against the artistic framework of Joachim Trier’s latest psychological family drama.

In our “Cinemails” column, two writers exchange viewing notes on a recent theatrical or streaming experience and/or dig into something more broadly philosophical about the movies.

In the current movie landscape, where it’s more common to watch or read about films or shows that are becoming spiritually gutted and spoon-fed to audiences, Danish-Norwegian director Joachim Trier isn’t making concessions. If anything, he and long-time writing partner Eskil Vogt have been elevating their craft over time, creating more complex narrative dramas instilled with disarming humor.

Personally, I’d argue their breakthrough came in 2011 with one of the century’s truly incredible character portraits, Oslo, August 31st, but Trier really received a boost of international attention 10 years later in 2022 after the festival-circuit success of The Worst Person In The World. It’s valid to attribute much of that success to the film’s honest representation of Julie (Renate Reinsve)’s pervasive indecision and independence, as she heads into her 30s without a genuine desire to follow traditional life goals. It was also, at once, a convincing spin on the time-tested tropes of the romantic comedy.

Vogt and Trier follow up that revelation with a more family-focused affair in Sentimental Value (2025), which opened in the Madison area at AMC Fitchburg 18 in late November, and has continued screening thereafter at Marcus Point Cinema. It will also open at Flix Brewhouse on Friday, December 12.

Rather than hone in on the spark of romantic relationships, Sentimental Value flips the script to center a splintered, emotionally distant family (the Borgs) and their Oslo home, which is haunted by prior tragedies. Their lives have all flared out in different directions, but the primary friction sustains between father Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård) and Nora (Reinsve), whose careers have drifted towards the arts—Gustav, the film director, and Nora, the live-theater performer.

Considering that potentially platitudinous set up for a Scandinavian art-house film, the structure and tone deliver a rich and contemplative experience (though, arguably). Reviews of Sentimental Value tend to use a cursory framing of it as “novelistic,” which is a far cry from the concise poetic timeline of Oslo, August 31st, for instance. Though, in their arcs, both works seem to fundamentally ask: are we capable of change and self-forgiveness? Sentimental Value further inquires about the role art plays in our lives, trying to evade the whole “one imitates another” truism. But is that ambition triumphant or middling?

In the past week, contributor Lance Li and I shared largely divergent viewpoints on the film—though, our interrogations generated a wealth of intriguing dialogue about character relationships in Vogt and Trier’s narrative and substantive comparisons to directors through cinema history (notably, Olivier Assayas and Ingmar Bergman). These exchanges also prompted a revisiting of The Worst Person In The World, some scrutiny about the designation of an “Oslo trilogy,” and even facilitated some meditations on our own families and backgrounds shaping this film’s resonance or irrelevance. —Grant Phipps, Film Editor

Editor’s note: The following conversation contains spoilers.

Grant Phipps to Lance Li

subject: “Sentimental” sentiments

I should preface this reaction by providing a little history of my relationship with Joachim Trier, which has colored the way I’ve seen all of his films since Oslo, August 31st in 2013. At that time, I was a little envious of the writing and the impressions of the coastal academics, and I was trying to expand my taste through their endorsements and sort of live vicariously through their prestige and influence in a way that only certain small-time writers might know, ha.

After that viewing of Oslo, I felt so validated in the simple pursuits and interests that got me to that point in my viewing history. Proof of symbiosis between artistic meditations, and art being a form of self-therapy, even just provoking me to write about the debated topic in a rarely read blog. It wasn’t my first film-diary “eureka” moment, but I was entranced by the way Trier had captured the tortured, recovering addict, portrayed with such grace and erudition by Anders Danielsen Lie (who has since appeared in most of Trier’s films, including Sentimental Value as thespian Jakob). Trier and his co-writer Eskil Vogt brought such an authenticity to representing not only the character of Anders at a crossroads in his mid-30s, but also just the interconnecting presence of the city of Oslo—a place I’ve wanted to visit since Ulver was my favorite band for a spell in the late 2000s.

So I’ve been tuned into Trier’s empathetic filmmaking for more than a decade, but I lament rarely having the opportunity to see his films with an audience. When Thelma quietly crept into local theaters so briefly eight years ago at the new AMC Dine-In 6 at Hilldale, there couldn’t have been more than one other person in the rows behind me. Four years after that, I watched The Worst Person In The World at home through the Chicago International Film Festival’s short-lived virtual cinema. That Norwegian film, so surprisingly to me, became Trier’s most successful and widely acclaimed—even after he had made an English-language feature in 2015, Louder Than Bombs, with renowned stars like Isabelle Huppert and Jesse Eisenberg (which I also missed theatrically). So the opportunity to see this one with my friend Oliver—making last-minute plans on Black Friday before an impending snowstorm—felt comfortable. And there were at least 10 others at the AMC in Fitchburg that late afternoon.

Sentimental Value is, naturally, a continuation of the sophisticated mood that Trier and Vogt cultivated in The Worst Person In The World. It, once again, offers up a meaty part for the range of Renate Reinsve as eldest daughter Nora in a troubled, if financially secure family, in the shadow of her film-director father Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård). If that seems like the narrative framework for a novelistic, Bergman-esque psychological chronicle of a family, it is. Trier and Vogt’s more simplistic, poetic style in Oslo, August 31st has evolved into this. I’m also noticing each Trier film creeping up a little bit more in terms of minutes, with Value running 133. The scope is obviously grander, though, taking place over a sustained period (as opposed to Oslo, August 31st‘s mere one day). Worst Person and Sentimental Value deal with significant stretches of time or character evolution which makes it feel that whole years have passed, even if the film timeline is slightly more compressed as it is here.

I think I’d be bothered by the density here more if I sensed a significant drop in quality and attention. The subject matter is familiar to anyone who knows their Scandinavian art-house cinema, as referenced above; but, this is a film so clearly made with loving attention. Observe its prologue montage of the Borg family house, enigmatic voiceover, and clip of Terry Callier’s ’70s Chicago soul epic “Dancing Girl.” In the next scene, Trier takes us behind the curtain to the theater, where stage actor Nora (Reinsve) is having a combination of stage fright-panic attack before she’s asked to initiate the show. The juxtaposition of styles and even places here is striking, and I appreciate how Trier and Vogt don’t continue to wind up the story laboriously. The pair offer us a window of sorts into childhood imagination—a metaphor which then visually spans a seemingly great deal of time within seconds—and then throw us into a heightened situation in the present with a sliver of context. Yet, they manage to create something of an artistic throughline in Nora’s ambition.

One thing I miss from Trier’s earlier efforts, though, is a little more cohesion and succinctness in the narrative. He’s been working with editor Olivier Bugge Coutté for his entire career, and yet the pacing and style in these last two films is somewhat flavorless in the stark cut-to-black manner of scene transitions. Instead of more fluid stanza breaks (to continue with my poem-novel analogy), Coutté is going in hard on the chapter or scene breaks. But these are often cuts without cliffhangers. They’re just like rests in sheet music, taking a two-second beat, not necessarily because it feels integral to the dynamics, but because of the scale and the duration here is over two hours.

I’d like to delve more into the minutiae of the relationships and how the film explores them, but I don’t want to ramble on endlessly, so I’ll save that for my reply. In the way I’ve set up the film, how do you feel about the running time? Were you comfortable with it in relation to its scope? Or do you feel like it should’ve been expanded or retooled somehow?

Looking at Sentimental Value‘s place in the Trier canon, I also thought about the prior designation of the “Oslo trilogy,” which ended with Worst Person. Clearly, this film should belong, too, right? Have I missed something? Demand his reclassification of a quadrilogy, ha.

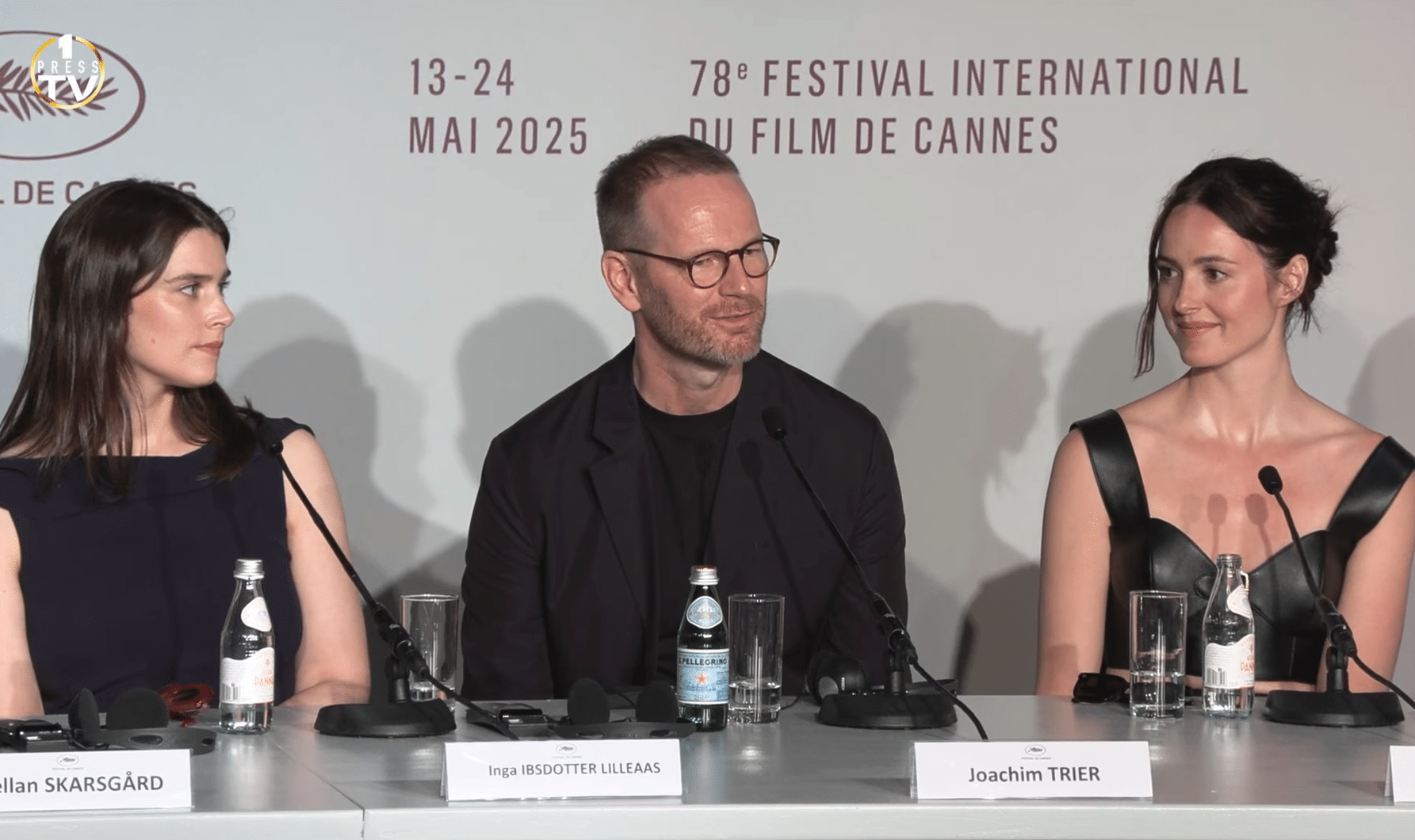

To bring Trier’s POV into it, and give him a final word, I caught part of the 2025 Cannes press conference for the film’s premiere recently. He quite confidently spoke about his roots making punk skateboarding videos 25 to 30 years ago before concluding that, for him, “tenderness is the new punk. It’s what I need right now. I need to believe that we can see the other. I need to believe that there is a sense of reconciliation. That polarization and anger and machismo isn’t the only way forward.” An inspiring expression in these times; but was that, for you, reflected as assuredly and consistently in Sentimental Value?

Lance Li to Grant Phipps

re: “Sentimental” sentiments

I’m sorry to say that I’m not as familiar with the Nordic movie scene as you are, Grant. I have nothing but goodwill for Joachim Trier, as I recall loving The Worst Person In The World a few years ago, though the details escape me. So I’m probably the “worst person” to ask about how this new release situates in his filmography. The thing is with temperament, I suppose. The middle-brow view of the world, with civilized, understanding characters, in comfortable middle-class homes and occupations, with their often ill-defined psychological troubles, has always seemed to me fictitious and alien. Now I’m not saying that it is a false representation, only that I’m skeptical of how much has been pruned out in the process, and how much of what’s left came out of self-pity and affectation. There seems to be some kind of a cushion built into these movies, padding down the dramatic conflicts in false grace notes, which is actually antithetical to Chekhov and Strindberg. They have the safety and self-affirmation that middle-brow audiences look for, which is why they tend to be winners in the festival circuit as opposed to more challenging works (Drunken Noodles from this year, for instance).

A lot of this is very generalized of course, and, surely, safety and self-affirmation themselves are nothing to think ill of. One can still muster up considerable respect for Edward Yang’s mellower, gentler works in the ’90s from A Confucian Confusion (1994) to Yi Yi (2000), turning away from the unsentimental despair of Taipei Story (1985) that struck very close to me for how much it reflected my own family roots and upbringing. If I couldn’t extend the same feeling towards Sentimental Value, it is because the dramatic crux of the film, to use an old critic’s jargon, has “nothing under it.”

We open on a swell idea: family history as told through the house, all the laughter and tears and heartbreaks it has witnessed and so forth. Obvious right from the outset, this house that has been hosting this family for more than three generations clearly meant the world to these characters, hence the “sentimental value” of it. Not a new idea, least of all not for Europeans. Olivier Assayas has done it with Summer Hours (2010), with none of the half-hearted psychosexual dross and twice as much real feeling, if only because Assayas treats people like people, and the house like a house. The fate of the house (Will it be sold? What will it turn into?) weighs on you. In Sentimental Value, it barely even stays on your mind, and often you can’t quite distinguish the interiors from those of other houses in the same film.

The house’s also not Sentimental Value‘s only idea, as it wasn’t for Assayas. Here we have the usual emotionally troubled woman, well played by Renate Reinsve. As a performer, she’s resourceful enough to take a scene and make it move in her own long-limbed rhythm, and her big-pupil, round-faced presence is stark enough to infect every rest of the frame she’s in: the shiniest spot you can scarcely take your eyes off of, and the most immediate thing you register when you begin to take it in. But resourcefulness can’t overcome a half-shaped character, all drawn up in big curlicues. When Nora’s in a state of angst, the angst doesn’t spring from within her. There’s too much self-consciousness in her teary mugs to fool us, and the source of her breakdown was never clear to us, not even intuitively. She floats too high above the character to stay in it, to make up for the part of it that’s left to suggestion by over-suggestion. It’s an award-favorite kind of exhibitionism: you get the nagging sense that she’s acting rather than playing. Adam Nayman for The New Republic, with his usual crap, says that the “myriad hang-ups and anxieties of the thespian class are well-trod territory, but Trier is a clever filmmaker; his editing choices [in the backstage sequence] underline the idea that Nora’s bout of stage fright is its own form of tour de force. He cuts away the moment she finally hits her mark onstage. We’ve already seen the performance that matters.” Yes, that is if you think “hyperventilating and literally rending her garments” is all it takes to be “clever.”

In a later scene, Nora confesses that she finds relief in performing because it allows her to find characters that open up new possibilities to her. The catch to this is: we don’t know who the character is she was supposed to play, on stage or off. The “artistic meditation” rings hollow. Ambiguity is all well and good, and people like Dreyer and Bergman had dug up riches with it. But it isn’t the same when you leave the drama and characterizations under-formed, even unformed. The basic problem with Sentimental Value is that too much of it is left not to ambiguity, but to wishful thinking, leaving out the work that goes into ambiguity. It’s a drama with its trunk missing, and an actors’ movie in the worst sense: they’re doing practically all the work of shaping the material, finding the tone to each relationship, filling in the blanks, never managing to find unity in any of the through-lines.

Stellan Skarsgard, as Gustav, and Elle Fanning, as his American fan and movie star Rachel Kemp, have enough tacit rapport together to suggest more than mutual admiration, and they share some scenes where their attraction seems within reach (not the only pair in the film that does this), but then as the film develops it doesn’t go anywhere, with neither of them realizing or reflecting on what they thought they saw in each other, or anything else. What did Rachel see in her part for Gustav’s script that she thought was actually Nora? What did she see in Nora when she met her that gave her the idea that she can’t live up to the part? There were so many loose strings like this that the total effect is that of a big hole in the center where the content and meaning of the drama should be. It’s not ambiguity. It’s blank postures for depth and prestige, and it’s irritating. It’s not like a vérité documentary, where you’re forced to work with unsolicited content, and it’s up to you how those faces looked, and from there you can dig deeper. This is a movie, framed and contrived and acted like one, and it should have the shape of one.

Grant Phipps to Lance Li

re: re: “Sentimental” sentiments

…Are you calling me “middle-brow?” I’m kidding, lol.

I apologize for prefacing my take with viewing history and awareness of Trier as a director, but I think it’s helpful to understand the context in which I’m aspiring to fathom a work of art. If you see that is rather tangential or superfluous, that’s fair, as it’s generally information left out of critical assessments.

Your own impressions are incredibly sharp, though I guess I’m a little surprised at you dismantling so many of its layers, ha. Your points are sensible, and I appreciate how you initially frame the narrative as existing in a world that “seems fictitious and alien” to you. I think that is always a risk with these sorts of Western-world dramas that focus on the woes of a definably white family with generational wealth. These days I try to refrain from casually pulling a loaded name like “Ingmar Bergman” out of thin air, but his works seem like a direct inspiration for the scope of the tension between the largely absentee father (Gustav) and his two daughters (Nora and Agnes, the latter played by Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas). I’m from a small, aging family who’s become even smaller and more separated over time. There are people on my father’s side, long-estranged, who I’ve never met and don’t even really know about. So, perhaps seeing this all dramatized for the cinema screen in various instances has offered some kind of vicarious catharsis or sense of closure to those haunting, unanswered questions and unresolved trauma throughout my life. This is not to burden you with all that; it’s just, you know, heavy.

I further appreciate you sharing your relationship with Edward Yang, another filmmaker I greatly admire, especially in his rigorous depictions of family in films like Yi Yi. In terms of cinematography and composition, Taipei Story might actually be my favorite, though I think you’re right in characterizing it as colder and alienating—everything is positioned in the frame as a kind of disconnection. The Assayas-Summer Hours connection to Sentimental Value you put forward is one that was in the back of my mind while watching this Trier film (and one I jotted down in my notebook towards the end); what’s interesting, though, is that the more I think about it, Assayas’ approach and tone in recent work is probably even more applicable, à la Clouds Of Sils Maria (2014). On the surface, the premise for Summer Hours—a family of siblings coming together to, fraying apart from their childhood home at news of their mother’s ill health—may seem like more of a direct line.

I wanted to reference Worst Person more consciously in my response, and so I just re-watched that for the first time in four years. I remembered so many details I thought I wouldn’t (Julie crashing the wedding reception where she meets Eivind and the third-act confrontational TV interview with Aksel that is resurrected here—this time, somewhat involving the hyper-relevant topic about Netflix / theatrical distribution), but I also was surprised by the breezy pacing of Worst Person, despite it having that novelistic 12-chapter structure. I don’t think that is quite as true here. The arc of Sentimental Value is more complicated to contain, and therefore I think it tends to drag in spots and feel a lot longer, even if it’s only an additional five minutes in duration. In fairness, I’d have to also give it another viewing for me to grasp and interpret all its intentions. You don’t seem bothered by running times. If I’m wrong on that assumption, feel free to expand your feelings, because I am curious if you often think about running time while you’re watching a film. It’s been a hot topic for me in the past several years.

The relationship between these two films is inextricable, to again echo my prior confusion about why there even is an “Oslo trilogy” if this isn’t intended to be a part. While The Worst Person In The World teases this thorny family dynamic between Julie and her father, it never fully brings it to the surface; it’s just a detail in her sometimes spontaneous, sometimes measured life choices right before and after she turns 30. Sentimental Value goes the opposite route, and foregrounds all the messy family issues. It’s like Vogt and Trier conceived both of the films simultaneously, or at least jotted down a synopsis for brainstorming later. All the other similarities with the lead actor, Reinsve, help bring that into focus as well.

To speak to your point about the film leaving its drama and characterizations under-formed: “Too much of it is left not to ambiguity, but to wishful thinking, leaving out the work that goes into ambiguity. It’s a drama with its trunk missing,” you wrote. That’s quite an evocative statement, and I can agree with that from the angle of what Sentimental Value wants to communicate about mending familial relationships (perhaps antithetical to an expression Aksel offers in Worst Person: “You have to make your own family.”) and what it’s effectively able to do in balancing an essential familial triptych. That’s, once more, a reflection of the screenplay’s strained ambitions.

When the Sentimental Value theater experience ended the other week, my friend Oliver and I walked into the AMC lobby to share some preliminary thoughts, and I said that it’s likely that audiences might not even perceive Nora as the main character. That’s a deception or distortion, maybe accurately reflected in the main fragmentary North American poster design. Julie (Reinsve) is very clearly the heart and epicenter of Worst Person, but there’s like a 20-minute section of Sentimental Value where Reinsve’s character Nora doesn’t appear. It’s either all about Gustav thinking he’s found a muse in the American actress Rachel Kemp (Fanning), or it’s about Agnes looking into the disturbing abuses to their late mother Karin (Vilde Søyland). I think, in this frame of mind, the narrative could either use some further expansion or distillation, because there’s just so much that’s being addressed over a period of 80 years, really—dating back to Karin’s horrifying abduction during WW II in 1943. This thread could honestly be a film in itself, but it’s reduced to montages here.

Your questions about Rachel Kemp’s role in the film might be answered more plainly, though. She’s the transient character, the outsider here—being American, for one—who is hungry to take on a prestige role or make an unexpected, lucrative career move that could turn out to be a breakthrough. Her interest in working with someone like Gustav is built on childlike allure from the moments she spends with him on the beach and a bit of artistic envy. I don’t think the film pulls any punches when it comes to her being a stand-in for Nora or her eventually recognizing that. Whether you find that element clunky or eloquent will, of course, vary. Gustav originally offered Nora this film part, despite her reputation as a theater actor; but because of their inability to communicate without an air of condescension, Nora didn’t want to try to work out their differences on set, knowing it would only bring about more strife (for herself, for the crew, and who knows who else). Rachel getting involved in the role written for Nora doesn’t solve anything or help bring Gustav’s film project to fruition, though; and Rachel’s increasing self-awareness (asking Gustav about dying her once-platinum blonde hair, affecting an accent, making the film in English as opposed to native Norwegian) lends a sensitive and knowing dimension to her character that is otherwise a bit thin.

I think what Vogt and Trier achieve in the screenwriting here is most striking and admirable. Maybe you don’t agree (well, I guess you predominantly don’t), but I’m inclined to point out the subtle subversions. The cliché is that any film-director character in a narrative film is a cypher or a thinly veiled surrogate for the actual director himself (yeah… all men, lol). But that doesn’t define Trier’s Sentimental Value. If there’s autobiography in the film, it’s harder to parse out. This complexity would be tempered or dully transformed into meta satire in a lesser work. Sure, this film is imperfect, but I absorbed it with the thought that Vogt and Trier think highly of their audience. And I haven’t even nodded and winked to its greatest joke, one for the cinephiles, during the gift-giving part of Agnes’ son Erik (Øyvind Hesjedal Loven)’s ninth birthday party. No spoilers.

To circle back to the Cannes quote I grabbed, which you seem indifferent about (though I welcome debate or comments), even if Sentimental Value fails in that regard—to provide reconciliation, and rail against polarization and machismo—it’s touching to hear a renowned male director speak that way when there are others out there just spewing toxic bile for attention. Joachim Trier is the kind of artist who wants to make something universally valuable, and who understands the world’s present, precarious moment. Sure, this is a heavy film, but it’s punctuated by humorous introspection. While your criticisms are wonderfully considered, Trier doesn’t strike me as someone who would dismiss what you had to say. He seems like a person open to dialogue, and that’s really what Sentimental Value is about. I’m glad he’s around, continuing to push forward, seeing the light, and making art with a crew of friends he’s known for two decades now.

Lance Li to Grant Phipps

re: re: re: “Sentimental” sentiments

Sorry, Grant, I didn’t mean to leave the impression that your moviegoing experience when it comes to Joachim Trier is “tangential.” Personal context is important when it plays into your critical process, and you’ve made clear how much Trier’s work means to you. I just didn’t know how to respond in a way that could complement it, as I’d liked to. I can see some echoes of my own family too in this film, but then many films do, and this one doesn’t reach out to me the way even a clumsy job like Left-Handed Girl (2025) did. And I don’t mean “middle-brow” as implying you, or even necessarily as a put-down. I wanted to clarify what I meant by “temperament” and why films like Sentimental Value tend to feel pat to me.

Running times can bother me or they don’t. The issue is that when I want to see a film work for me and it fails, I’d like to know where and when and how it fails, rather than how much shorter it could’ve been. If it takes Sentimental Value four hours to gather all the subtle tensions and flesh out, that’s okay with me. I doubt that it will, though.

I also did not have an issue with the way Gustav-Kemp relationship was set up. I can see the logic of an outsider filling in an insider’s shoes, or as an imperfect solution to the conflict involved in casting the part, or Fanning. And I rather liked the way she brings the childlike geniality to her shallowness, becoming aware that the part was for Nora. The issue I had was with how it’s treated. For a movie about reconnecting with your own family through art, it seems incredibly apprehensive about showing the “art” and the artists’ relationship to their art. I don’t see anything of Gustav’s supposed mastery in any of the clips we’re shown, except technically—and it doesn’t take a lot to be technically accomplished—nor any of his personal connection to it except through what’s been handed to us perfunctorily outside the clip. Nora’s performances were almost always cut away from. There was one moment when she breaks down sobbing, and the camera unveiling the diegesis of her performance is a nice touch, but, like I said, there’s “nothing under” the breakdown. The dramatic put-on doesn’t feel earned, and so you’re not sure if you’re supposed to applaud or scratch your head. Likewise with Kemp: what about her part is so distinctively and unmistakably Nora that even she couldn’t help notice and being unsettled by it? So much so that she wanted a more Nora-like appearance?

The idea, in the end, is clearly that, somehow, only Nora could do it justice. Yet when we get to Reinsve’s performance at the end, she was so facially overwrought and physically stiffened, that it’s like a Jeanne Dielman caught in a three-ring circus of Academy earnestness. What about it that says anything about Nora as a character? She never struck me as someone who had suicidal impulses as is claimed to be, not even remotely. Yet the story hinges on suicide as if it’s the key to Nora and Gustav’s (even in-progress) reconciliation, when we’re totally in the dark on the emotional context. Their coming together at the end rings hopelessly false.

It matters less to me whether Gustav is a stand-in for the filmmaker. The birthday gift joke is a nice touch, along with Gustav’s naivety when he complains that the problem is not having enough artistic freedom. If Gustav is only his own character, wonderful, but I’ll need more than that. The trouble is, the dramatic conflict between him and Nora was never defined. I don’t need it spelled out, but I don’t need guesswork on a blank either. I couldn’t take their show of conflict at face value. If it really just comes down to Gustav’s absence as a father in Nora’s life, then how specifically does the conflict manifest? How do they really feel towards each other? Lukewarm to the point that they’re barely on speaking terms? Or actually distant? Gustav said he wanted to talk to Nora, but about what? If, confessedly, he can’t bear the sight of her performing onstage, why doesn’t it feel like that was the case? What does he realize about her, besides that he’s no longer a spring chicken, that all of a sudden he wants to make up for lost time? (And it’s lazy to make the link between Nora and Gustav’s mother—in what way does that make any emotional sense?)

See, I don’t think it’s at all messy or heavy. A director like Jean Renoir’s compassion draws us closer to even characters most unlike and distant from ourselves. He is gentle, and so is Trier. What separates Trier from Renoir’s gentleness, and what brings it closer to “genteel” in my opinion, is his cleanness, and I don’t just mean the sterilized Nordic bourgeois milieu. For all the shit I think of Arthur Miller, he doesn’t shun mess, for the very good reason that mess is in the very identity of drama, that real human relationships are but a series of endless, unresolved clutter of embarrassments and blatant, stupid mistakes—he just slants it mawkishly and makes a fool of himself.

I’m recently on a rewatch cycle of Magnolia, which I didn’t care for when I first saw it a couple years ago. What struck me, as what I was put off by then, was just how rough and messy it all is. An affectatious melodrama with a shot of Eugene O’Neill in the arm: depthless characters expressing exactly how they felt in thick, verbose underlines—very jarring in execution, but that’s precisely the source of its power. It wouldn’t have been as good had it made more “sense” or been more “coherent.” The melodrama of cancers and the estranged sons and daughters reaches a point that’s so absurd and maudlin that the absurdity is reified in “what the frogs!,” and the “F-A-K-E-R-Y” and “C-O-N-T-R-I-V-A-N-C-E” that were always there are now read aloud and spelled out in big letters.

Sentimental Value doesn’t need over-the-top, but it is free of that mess that gives drama its meaning. It seems ashamed of its identity as a family drama. It doesn’t push your buttons, but then it doesn’t do anything else, except having characters burst into tears now and then to convince you that it has deep feelings to sell, like a beautiful rug covering an empty ditch—you couldn’t sense the emotions buried underneath like you could for Taipei Story.

I can sympathize with Trier’s appeal to “tenderness.” We need it as a culture more than we need showy doom and glooms. But I’d like to think that it takes something else than what Trier and Vogt have got in Sentimental Value to make that “tenderness” felt—it takes guts to be tender, the guts to face the conflicts and uncomfortable truths.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.