“Eat My Words” offers much-needed time to reckon with environmental impact

Take a quiet hour, and explore the mixed-media exhibition in the James Watrous Gallery at Overture Center through October 12.

As I write this, pea plants are twisting lime green tendrils toward the light in the James Watrous Gallery on the third floor of the Overture Center. Just behind the showy peas—which are potted in geometric, unglazed clay pots—there is a box where worms munch paper and food scraps. The compost made by the worms becomes soil for the peas. The peas become fiber for handmade paper. The paper feeds the worms. And on and on.

The plants star in the titular installation in Liz Bachhuber and Jill Sebastian’s show, Eat My Words, which is open through October 12, 2025.

Eat My Words is the most literally alive work in the exhibit, but if you stay long enough, the other pieces come to life as well. A large piece is made up of dozens of driftwood sticks wrapped in silk neckties (Maelstrom, Bachhuber). Old refrigerator doors from East Germany with Canada geese carved out are backlit with light pulses to simulate migration (Ice Birds, Bachhuber). A table holds stacks of handmade paper made from Sebastian’s garden waste (My Garden, Sebastian).

The show is best consumed slowly. I happened to visit the gallery on a chilly, quiet September afternoon. The kind that feels out of place in our new reality, the climate-changed summers that often stretch well into September days. It all felt eerily normal as the late-summer sun cast warm spots throughout the gallery. I calmly sat on a bench for perhaps the first time all week. I am not often slow these days, as I consume infinite scrolls of destruction and disaster. We need more time to process the grief than an Instagram algorithm can provide.

One of many stunning works in the exhibit is Sebastian’s piece, The Limits Of Paradise, which offers space to step back to perceive the bigger picture. Grids made from tree of heaven sumac stems—a plant considered invasive in North America—form the foundation of the piece. Woodblock-printed house sparrow wings flutter on the grids alongside reproductions of fliers dropped from U.S. planes over war zones. “Birds, weeds, and propaganda ignore borders,” the nearby didactic panel reads.

From my sunny bench, The Limits Of Paradise danced behind the table holding My Garden. I wondered… If you planted the paper, would it grow? It feels, in this time, like we are all suspended and waiting for a cue before we split our seeds and push up out of the dirt en masse to demand sunlight and air.

Outside of Eat My Words, the exhibit consists of individual works by Bachhuber and Sebastian, two artists who met in grad school. Decades later they realized their work examines similar questions, and then they began a transatlantic conversation (Bachhuber works in Germany and Sebastian in the U.S.). The show feels like a conversation, about how to live better in relationship with birds, plants, worms, and each other. A conversation in which the viewer is also an integral part.

The exhibit also subtly explores whiteness and gendered relationships with the more-than-human world. As the exhibit description notes, Bachhuber and Sebastian work in two of the most powerful and environmentally ruinous consumer societies on Earth, and they are trying to reckon with what that means.

It reminded me of something that Potawatomi botanist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote in her book Braiding Sweetgrass: “As our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated, more lonely when we can no longer call out to our neighbors.” Sebastian, in particular, is clearly calling out to these neighbors in her work, Wasteland: Weed Stories, in which she shares not only information about the plants she has found in a 6-foot by 100-foot abandoned Milwaukee lot, but also about her memories with each plant.

So often, work exploring human relationships with nature can feed into colonial man versus nature paradigms. This exhibit seems to position the two as one and the same (a theme that is very common in work by Indigenous artists and writers like Kimmerer).

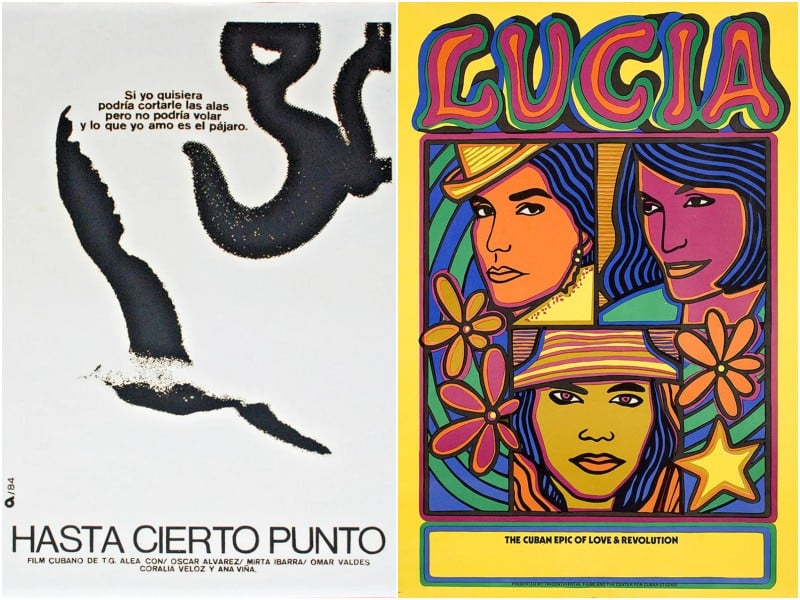

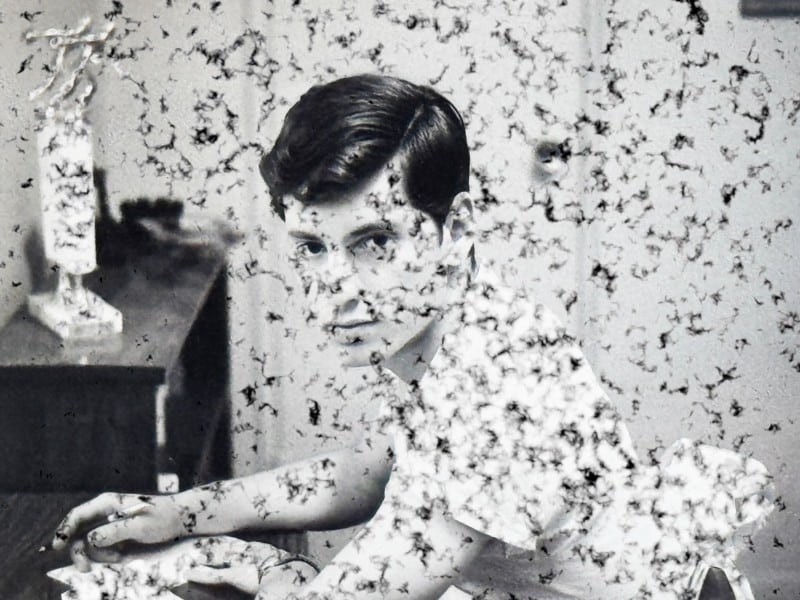

There is no wild place that is not human. There is nothing human that is not wild. Turn the corner from Bachhuber’s Ice Birds, and you’ll find a series of six black and white lithographic prints (Flying I-III). Three of the prints feature birds in flight. Above each, a print of a child is shown running, jumping, and being tossed into the air.

Eat My Words gives you permission to take a quiet hour and ask the art and yourself who you are, and what your relationship is to the natural world.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.