Could an exhibition like “Guiding Ethos” find a home in Madison?

A group show at Appleton’s Trout Museum stands up for “political” art in an era of cowardice and compliance.

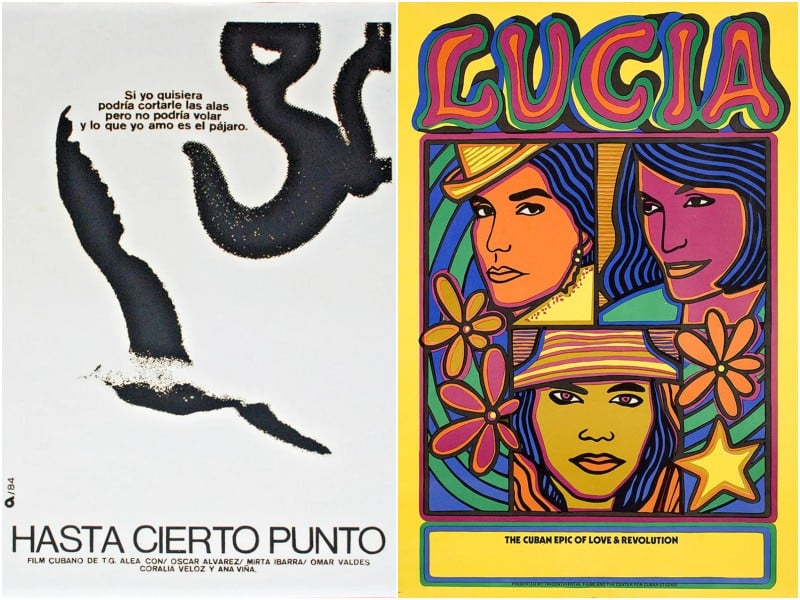

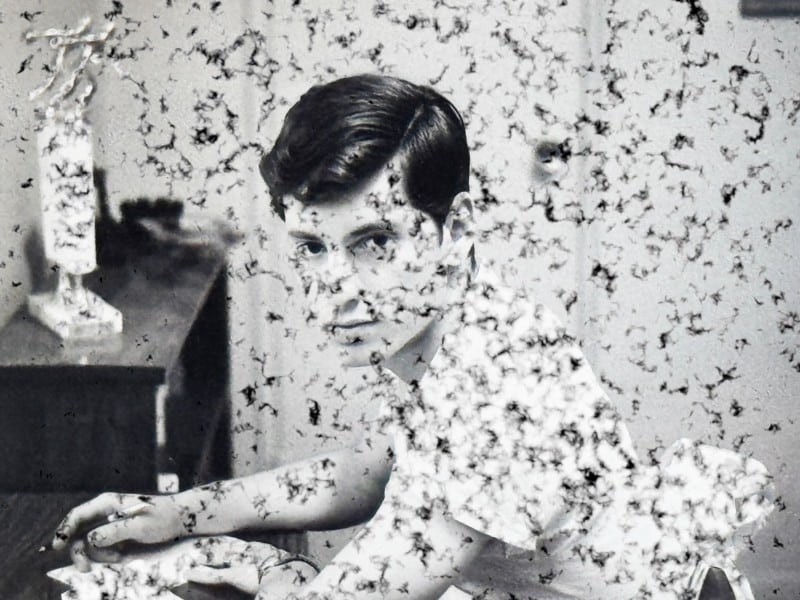

What’s immediately striking about The Trout Museum of Art’s Guiding Ethos exhibition is the breadth of artistic mediums and styles on display, from installations of found art, to digital videos, sculptures, paintings, prints, and textiles.

Fatima Laster’s “The Gentrification Welcome Runner” invites viewers to walk on 130 “Cash for Homes” signs the artist cut down from her majority-Black neighborhood in Milwaukee as a “reclamation of Black land and territory from aggressively infringing and displacement-centric outsiders,” according to Laster’s artist statement.

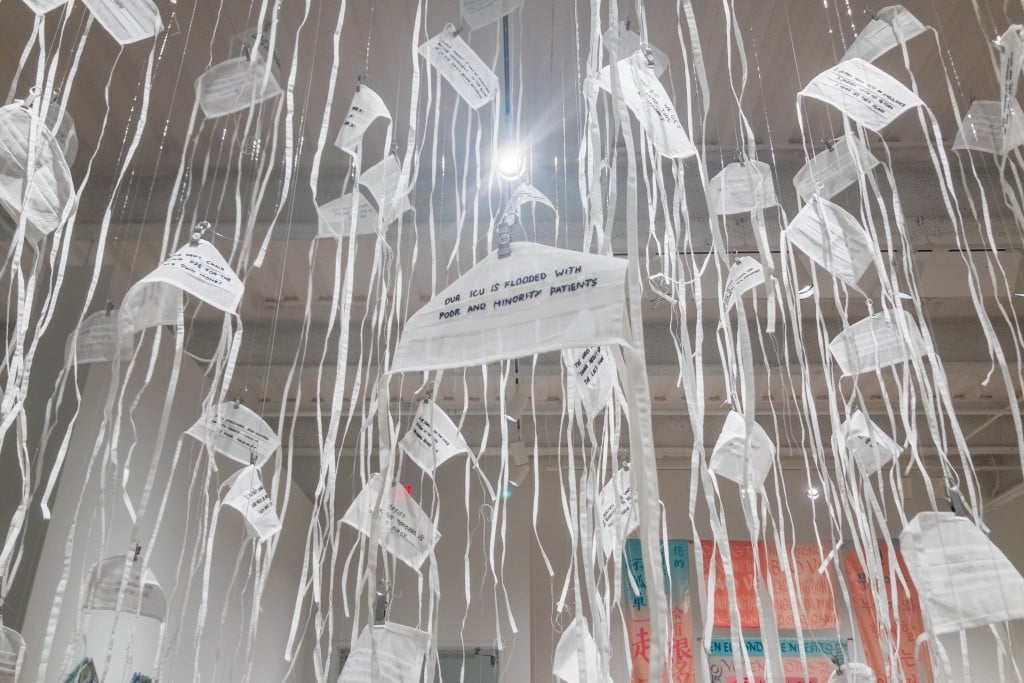

Nirmal Raja’s installation, “Feeble Barriers,” suspends a flurry of white organdy facemasks, many embroidered with quotes Raja sourced directly from healthcare workers: “The Navajo Nation has been really devastated by COVID-19,” “Our ICU is flooded with poor and minority patients,” and the upsettingly prescient “I am afraid we will see measles in children again if parents don’t bring them in for shots.”

Valaria Tatera’s “Endbridge Pipeline” displays three large jars, one containing water from the Bad River, soil from the Bad River Reservation, and water from Lake Superior, all labelled with their names in Ojibwe. Behind the jars is a curtain of shredded black plastic strips with the words “RESIST” in white.

Walking through the exhibition, the breadth of topics explored and sharp perspectives presented are particularly striking in our current era of fascist censorship and institutional compliance. The 25 artists invited by curator Jenie Gao “engage storytelling as both record and resistance,” according to its press release. “Through personal narrative, historical reflection, and collective memory, the artists in Guiding Ethos challenge dominant histories and imagine new futures.”

Gao has assembled an ambitious compilation of work from highly-decorated artists of diverse backgrounds exploring this moment’s most salient issues. You would think that such an exhibition would be right at home in Madison. About half of the artists either live in Wisconsin or have deep Wisconsin connections, including Gao, who now lives in Vancouver but was a prominent member of Madison’s art community for years. But Guiding Ethos is at the private Trout Museum in Appleton (325 East College Avenue), which Gao points out is a much smaller, more conservative community. And based on Gao and other participating artists’ experiences, they’re doubtful whether a Madison institution would house, much less support, such an exhibition or if they’d want to participate.

Whose art is “political”

Gao tells Tone Madison that the exhibition’s theme “came out of a lot of the work and the research that I’ve done previously, and this question of whether it’s possible to create ethical and honest work in the context of colonial systems—and, particularly with fine [art] work—both in the context of fine arts institutions, but also out in the community.”

The question of honest work in colonial systems and fine arts institutions raises the specter of censorship, particularly of art that is deemed “political.” But what makes a work of art political or apolitical? Gao says “all art is engaged with politics to some degree… people who make apolitical work have to make that choice to not engage in politics, or to treat their art as if it exists in some sort of vacuum, when it does not.”

“In [art], we see reflected the ways in which people debate and dissect how they place themselves in a specific moment in time, and what they believe is important to steward in the work that we exhibit, pay attention to, and ultimately preserve and archive,” Gao says.

“Art is always intended to say something, and even if you’re not saying anything, that’s an intentional choice,” says Nipinet Landsem, who is exhibited in Guiding Ethos. (Disclosure: Landsem previously contributed to Tone Madison as an illustrator.) Landsem points out that not everyone gets to be apolitical nor have their work and their perspective considered apolitical. “I feel like all art is political, but the goal of marking a certain subset of art as political, and the rest of it as not political, serves a purpose. And I think it’s to be able to silence voices that people don’t want to hear from, specifically people in power.”

“The art that gets deemed political tends to be made by marginalized people about marginalized experiences, and I think that deeming it political and then segregating it from the rest of art that is not about those experiences is just another form of silencing those voices,” Landsem says. “And obviously sometimes people are like, ‘Let’s uplift political art. Let’s specifically single out political art.’ But I feel like a lot of the time it’s used as a way to dismiss people.”

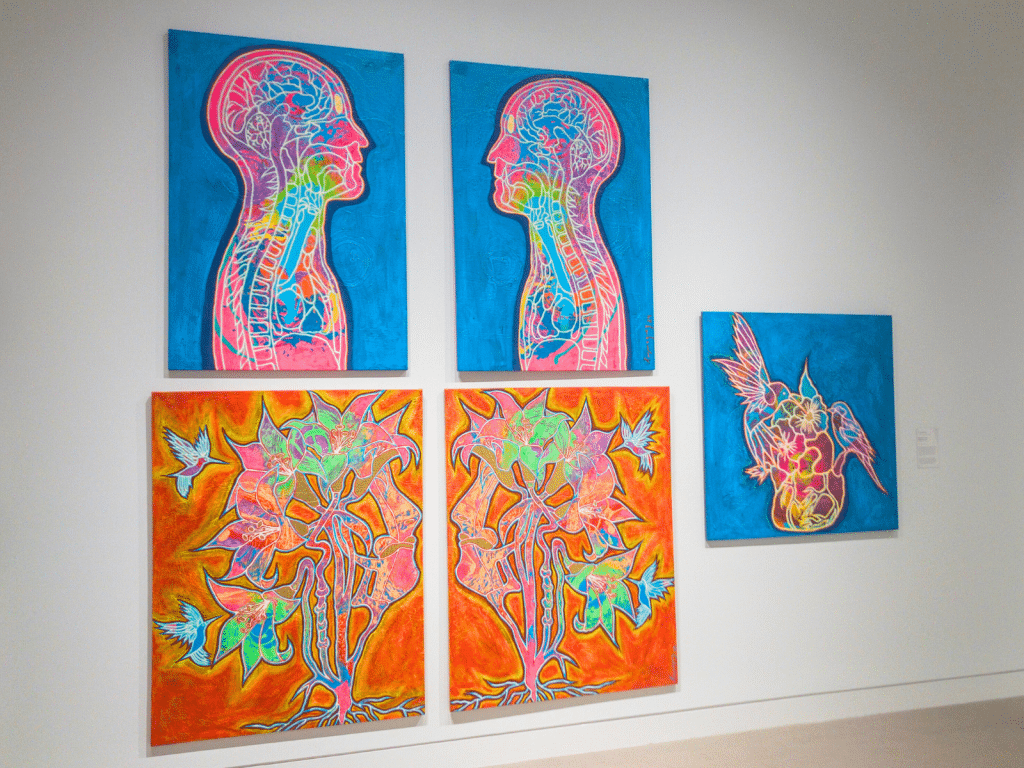

Richie Morales is a self-taught Guatemalan painter living in Madison who is currently very aware of the way his ethnicity and appearance have been politicized. “I have the Latino phenotype, which nowadays is the phenotype of otherness, or the phenotype of the enemy,” Morales says. “So I really feel it at some places. And it has a big impact on myself and on my existence. And one way to, let’s say, heal and try to reconnect with what is going on there is through artwork.”

In Guiding Ethos, Morales’ big, bold paintings explore the alienation of “techno-feudalism or techno-capitalism.”

“People are not able to connect with their being, and it feels like we don’t have any direction in which way we need to go,” Morales says.

Participating artist Emily Leach says, “Beyond whether or not art is directly engaging with political ideology, every art practice is politicized, because every aspect of existing, especially in highly contentious times, is politicized.”

Leach’s piece, “Residence Time,” references a quote from Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being: “This is what we know about those Africans thrown, jumped, dumped overboard in the Middle Passage; they are with us still, in the time of the wake, known as residence time.” Sheer embroidery fabric hangs in a long column, connected by embroidery hoops at the ceiling and the floor. Within the column, a small square is suspended, embroidered with the words:

To the bodies

of the drowned, the jettisoned

and those who walked into the water

suspended in residence time

Many of the works are in conversation with other works of art, history, political movements, and also in partnership with communities. The artists Gao invited to participate “have practices that are bigger than their studios,” they say. “So artists who have practices in some type of community, advocacy work, or care work, or any other roles that they play beyond their roles as fine artists.”

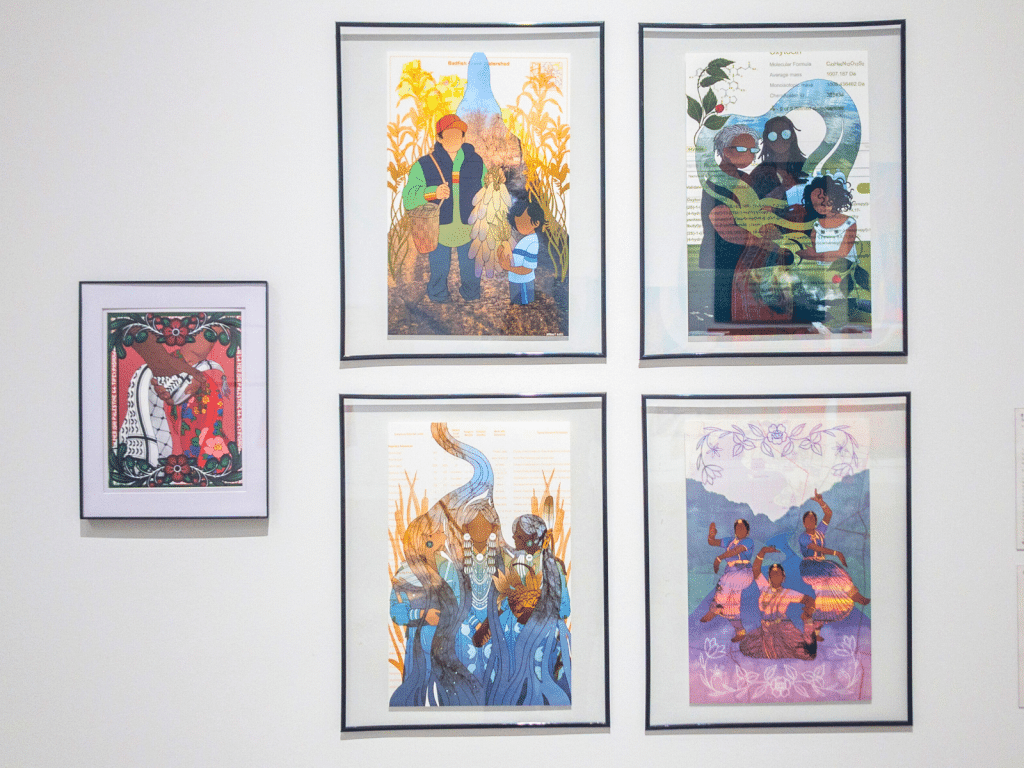

Landsem lives in Minneapolis now but lived and worked in Madison for years. In 2022, they were the artist and educator in residence at the Metropolitan Sewerage District. “The goal of the residency was to bring people together and encourage people to reflect on and share their experiences and their relationships with water,” Landsem says. They spoke with groups of Indigenous people and Black and brown people about their communities’ relationships to water, doulas “about how water has impacted successive generations, and also how they work with birth” as well as conversations about food sovereignty and global water access issues. The resulting four illustrations that came out of those conversations are on display at Guiding Ethos.

Many of the pieces in Guiding Ethos were created in partnership with communities. Even those that weren’t were made by people from marginalized communities—immigrants, Black and Brown people, and Indigenous people. It’s a reminder that when an artist is silenced for being “political,” as horrific as it is, it is not just the silencing of an individual.

Institutional cowardice

In these highly contentious times, art that is deemed “political” is seen as a risk that institutions are unwilling to undertake. Many of the artists referenced the Trump administration’s heavy-handed “guidance” for National Endowment for the Arts funding and other national incidents where artists’ opportunities were cancelled because of the subjects of their work.

While censorship has escalated under the current administration, it is not new, nor is Madison immune. In 2016, The Overture Center clumsily censored the feminist art group Spooky Boobs Collective’s exhibition, The Pattern’s Vicious Influence, a series of wallpaper patterns made with words commonly assigned to women. Out of fear of offending conservative donors, Overture hung curtains over the wallpaper patterns with words like “cunt,” “pussy,” “bull dyke,” “slut,” or “twat.” Pinned to the curtains was a card reading: “Explicit language / View at your own risk.” To view the work, patrons had to move the curtain to peek under it—an experience that was awkward and deadened “what is supposed to be a provocative, confrontational experience,” Tone Madison co-founder Scott Gordon wrote in 2016.

“There are absolutely limitations [placed] on diverse artists, and especially those who choose to use their work to express a particular political opinion or demonstrate solidarity with others that they also want to be safe in the community,” Gao says.

Some of the artists in Guiding Ethos have had their work censored because of the subject matter of their work. The Whitney Museum of American Art cancelled a performance art exhibition to mourn the deaths of Palestinians that Noel Maghathe created with two other artists. Apexart also cancelled an exhibition Maghathe curated because the brochure text referred to the genocide in Gaza.

Gao says Guiding Ethos “brings together artists, not only from different regions, but who represent a particular cross-cultural solidarity.” One thread was solidarity with Palestinians and voicing opposition to the genocide in Gaza. Several Guiding Ethos works express such solidarity, and the exhibition includes the work of three artists of Palestinian descent.

“Maybe nobody else is writing about these shows, but I at least have not heard of another exhibition or another institution that has showcased Palestinian artists, and certainly not showcased in the context of other artists who are expressing solidarity with them in the state of Wisconsin,” Gao says.

One of the artists expressing solidarity is Landsem. In one of their five printed digital illustrations, a human hand wrapped in a keffiyeh and another hand wrapped in a kokum scarf clasp one another. “I use that piece to draw a connection between the experiences of Native people in the U.S. and Canada and what Palestine is currently experiencing,” Landsem says.

Leach points out there’s no real way for artists to know what opportunities they were denied because their work was deemed “political.” Artists in particular are vulnerable because they are subcontractors, Leach says, “so we’re kind of consistently put in this position of selling our work, but also selling ourselves as someone that people would want to work with.”

“I think it can be really difficult to understand how to advocate for yourself, particularly when it’s so important for your work to be seen,” Leach says. “I think that’s felt across not just the arts world and visual arts, but in writing and other fields as well, especially when you’re working as a subcontractor.”

Leach was one of the Black women artists who participated in the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (MMoCA) 2022 triennial exhibition Ain’t I A Woman? which Laster curated. Leach was also directly involved in the fwd:truth movement that brought to light the racist ways MMoCA treated her and her fellow artists. She had her work pulled from the exhibition before it closed in protest of MMoCA’s response, or lack thereof.

MMoCA’s 2025 triennial did not include a single Black woman artist, which MMoCA director Paul Baker Pringle told the Cap Times was “a message, not necessarily directly to us or with intention, but there was a message to be taken.”

“[The message] is, ‘We need a break. We don’t want to be part of this new cycle. … We don’t want to deal with the drama of it. We just want to do our thing,'” Baker Pringle says. Baker Pringle’s clumsy statement fails to consider whether MMoCA could do more to repair its relationships with Black women artists so they do feel welcome and willing to engage.

“One issue that persists in North American institutions is that accountability gets confused with liability,” Gao says. “And because none of these institutions want to be on the hook for liability, they dig in their heels and don’t apologize for wrongdoing. They don’t want to admit that wrongdoing happened, because they see that as potentially grounds for legal action and other things that they don’t want to be entangled in. When that’s not what actual accountability is.”

“It was really a painful experience for me, and I think it made me feel very wary to engage with organizations or institutions,” Leach says. “Since then, I’ve been involved a lot in collaboration as one way of continuing to work in partnership with other artists, and that has been really fruitful for me. I have also been involved for the last five or so years in an artist-run organization as well, and one that’s really focused on centering on artists’ voices from their own perspective—not through a vector of curatorial interpretation, but literally just them relaying their stories.”

By contrast, the exhibition at Trout Museum of Art, Leach says, has been “a really positive experience.”

“I think that a lot of that, for me, draws from the fact that it is another artist-curator running this particular invitational,” Leach says. “I think that there’s a lot of institutional wariness right now, particularly in the midst of the political climate that we’re in, and I think that these are spaces that are incredibly transformative and can invite really meaningful conversations, whether intentionally or not. And it just means a lot to be in an exhibition that is so thoughtful.”

For many of the artists, having an exhibition like this in the Midwest, in a smaller city like Appleton, is significant. Wisconsin consistently ranks last or second-to-last in state funding for the arts and Dane County and the City of Madison frankly don’t do enough to counterbalance. But that doesn’t mean that artists living here aren’t making innovative art.

“People call the Midwest like flyover states, right? And it’s very dismissive,” Landsem says. “To have an exhibit like this in the Midwest says a lot about how people in smaller communities in a quote-unquote, ‘flyover state,’ actually feel. And how much we actually contribute to the greater project with whatever art we’re making.”

Gao says it was important to them that Wisconsinites see that Wisconsin and Midwestern artists are engaging with “national and international conversations” in a Wisconsin museum exhibition.

“People tend to think that the critical cultural conversations are happening in major metropolises, that you can only see cutting-edge contemporary art in New York or Chicago or LA, and that’s simply not the case,” Gao says. “And I would actually argue that some of the exhibitions that I’ve seen in recent years that are able to uphold some of the messaging that I aimed to curate and cultivate in the Guiding Ethos exhibition—they tend to be in smaller places.”

Now, if only Madison’s art institutions could follow suit.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.