Bus drivers bear the brunt of Metro Transit’s failures

The status quo—poor planning, and understaffing—doesn’t serve anyone.

The status quo—poor planning, and understaffing—doesn’t serve anyone.

On February 20, Metro Transit drivers did the jobs they are paid to do—and nothing more. They were not breaking any law nor violating their contract.

The results were noticeable to riders and widely reported in local media. The City of Madison’s statement decried the action “that disrupted a vital service that so many other working Madisonians depend on.” But why does our public transit system fall apart when drivers work their contracted hours?

Metro Transit depends on drivers to voluntarily work overtime hours to staff its existing bus lines. Each week, there are roughly 2,000 hours of overtime for the 250 full-time drivers at the agency. Most of this overtime work is performed by about 75 drivers, who work nearly 70 to 80 hours a week. A post on Reddit on February 20, 2025 by the account “Madison_Bus_Driver” announced service disruptions, as drivers were refusing to take the voluntary overtime, citing chronic understaffing and low pay.

Metro Transit drivers, as well as mechanics, service workers, customer service representatives, finance staff, and other administrative clerks are union workers represented by Teamsters Local 120. In Wisconsin, transit is one of the few remaining public-sector areas in which workers have retained full bargaining rights after then-Gov. Scott Walker signed Act 10 into law in 2011. The union has been bargaining with the City of Madison since its latest contract expired on December 31, 2024. The last contract was bargained in 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic but before the inflationary crisis that has pummeled workers’ real wages. Transit employees were designated as “essential workers” during the pandemic, and continued to operate bus lines during the “shelter-in-place” orders without hazard pay and often without proper personal protective equipment or PPE. Despite Metro workers’ efforts to bring these issues to the public’s attention as well as at the bargaining table with the City, drivers still don’t have the support they need to provide the quality service Madison deserves. Moreover, while their statement claims “the City of Madison is committed to supporting employees and their rights,” on March 3, City of Madison Employee and Labor Relations Manager, Kurt Rose, filed a complaint with the Wisconsin Employment Relations Commission (WERC) charging that the Union had engaged in an illegal slowdown.

Misplaced investments

Metro Transit has radically restructured over the past five years. Increasing bus ridership and developing Madison’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) lines were key planks in Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway campaign platform when she was first elected in 2019, and when she successfully ran for re-election in 2023. Rhodes-Conway did not renew the former Metro Transit General Manager Chuck Kamp’s contract in 2020. The City eventually hired Justin Stuehrenberg, who had developed the BRT system in Indianapolis. Stuehrenberg’s contract was renewed for one year by the Madison Common Council in January. Just three months later, on April 2nd, the City announced that Stuehrenberg had resigned to “pursue new opportunities”. Stuehrenberg operates as an independent consultant through JS Transit Advisors, active while he was serving his role for Metro Transit.

Stuehrenberg began his tenure by proposing a new management structure. Previously, there were managers for each of the major divisions within Metro: Operations, Maintenance, Marketing, Finance, and Planning. Stuehrenberg created new “chief” positions above these, which the City placed at its highest salary designation, Compensation Group 21: Operations, Maintenance, Development, and Administration.

Tone Madison reported in 2023 that in addition to salaries that range from $120,000 to $163,000, the City of Madison paid the moving expenses of the new Chiefs in excess of the amounts permissible by City ordinance. Three of the four candidates hired to these positions (Ayodeji Arojo, Rachel Johnson, and Anthony diCristofano) left less than two years after their hires. In addition to these new Chief roles, Metro Transit added more managers under the chiefs. Meanwhile, the number of drivers budgeted has actually decreased. In 2018, the City approved 325 drivers, compared to 302 in 2023; the number of mechanics has remained at 45 despite increasing the number of buses in the fleet.

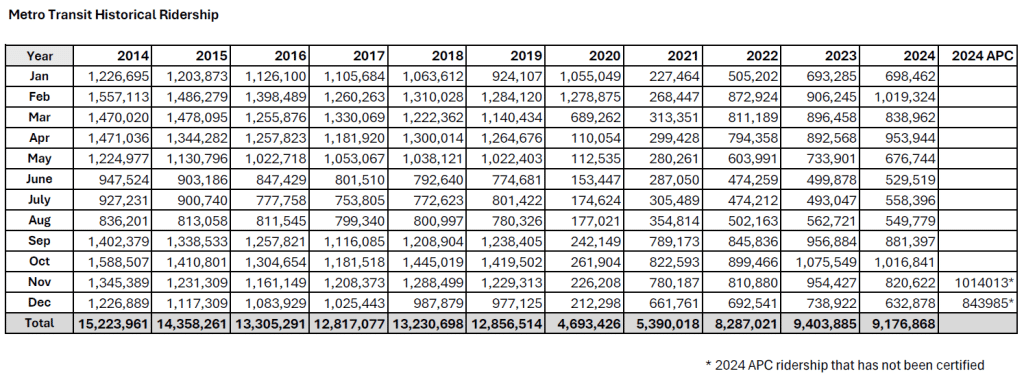

None of this seems to have significantly improved Madison’s transit system, or the lot of transit workers. In 2019, when Rhodes-Conway was elected, City of Madison figures show ridership at 12.85 million rides annually; in 2023 that figure was 9.4 million, and in 2024 it was 9.17 million. COVID-19, of course, seriously sank ridership figures, but ridership has struggled to rebound since 2022, when then-President Joe Biden “reopened” the economy and declared the pandemic over. In April, the City put out a new report claiming a 38.55% increase in ridership in 2025 (1,317,527) compared to the same month last year (953,944). That sounds like good news, but the City puts an asterisk on that figure when they report on their website that: “It was noticed in Spring of 2024 that there were issues with farebox data. Some buses that were dispatched to busy runs were showing as ‘0’ passengers in the data. Staff believed this may have affected thousands of rides.” It was also reported that “Some of the old fare box technology did not count accurately in its final months. In 2025 the way in which we count ridership has changed.” If the rides weren’t being accurately counted before, comparing “bad” numbers to “good” ones doesn’t leave us with a clear picture of what, if anything, has changed.

For transit workers, the 2021-2024 Collective Bargaining Agreement between the City of Madison and the Teamsters provided wage increases of 2.5% in 2021 and then 2% in 2022 and 2023. City of Madison employees without collective bargaining rights at other agencies were given 5% and 6% raises in 2023 and 2024. Factoring for inflation, transit workers took a pay cut.

Hazardous working conditions

Driving a bus is not an easy job. Drivers don’t work a straight eight-hour day; they have “pieces of work” that have to correspond to the peak times. Most drivers wake up at 3 or 4 a.m. to begin service before 6 a.m. for the morning commute. After their morning “piece” ends, they have unpaid time in the middle of the day, and then have to come back for an evening shift to drive afternoon or evening routes, and finally get home dog-tired at 7 p.m. or later.

Metro has the highest rates of Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and Workers’ Compensation claims among City of Madison employees—in no small part because drivers are doing sedentary work in a metal box that jumps up and down. Their jobs require them to speed 40-foot (or now 60-ft. articulated) buses through traffic to make unrealistic schedules and work for hours without designated restrooms, all while having to manage riders who are often difficult or worse. In late February, a driver crashed a bus into a local business when he was attacked by a passenger. And that’s to say nothing of the work that mechanics and office workers at Metro do.

These working conditions are also issues for riders. Both transit workers and riders have an interest in pay that retains staff. Riders want dependable, experienced drivers who know their routes and who they can trust to get them safely to their destinations. I’ve listened to enough customer service calls to know how important this is to people who regularly ride the bus. Bus drivers take overtime to make up for low base wages, are working stressed, and sacrificing their health to make a living.

At the same time, Metro needs to hire more workers who keep the system running, particularly bus drivers and mechanics. The system is strained as it tries to keep up with the service at its current levels—and that is with three million fewer rides than were taken just five years ago. If Madison wants to expand its BRT service, or even just improve the existing lines, it’s not possible to do that without expanding the workforce. The drivers’ concerted action of refusing overtime makes this point clear.

Lastly, riders and drivers could find common cause in Metro’s route design. The Teamsters’ contract is supposed to allow drivers to have some input on “run cuts” prior to their posting, but this is advisory-only. Riders depend on the buses arriving when they’re scheduled to be there, but drivers often know these to be stretched to the limit by transit planners. Imagine what might have been possible if there was a coalition of transit riders and operators during the route redesign in the summer of 2023, when neighborhood lines were eliminated.

These are sizable problems that won’t be solved easily or quickly. Let’s be sure to offer solidarity and support to working people who are on the front lines fighting for dignity, a better life, and a better transit system for all.

Editor’s note: The headline of this article has been changed.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.