“Broken Spectre” reframes the Amazon as an urgent, revisionist Western

Richard Mosse’s experimental environmental film is showing in MMoCA’s main second-floor gallery through mid-February 2025.

Richard Mosse’s experimental environmental film is showing in MMoCA’s main second-floor gallery through mid-February 2025.

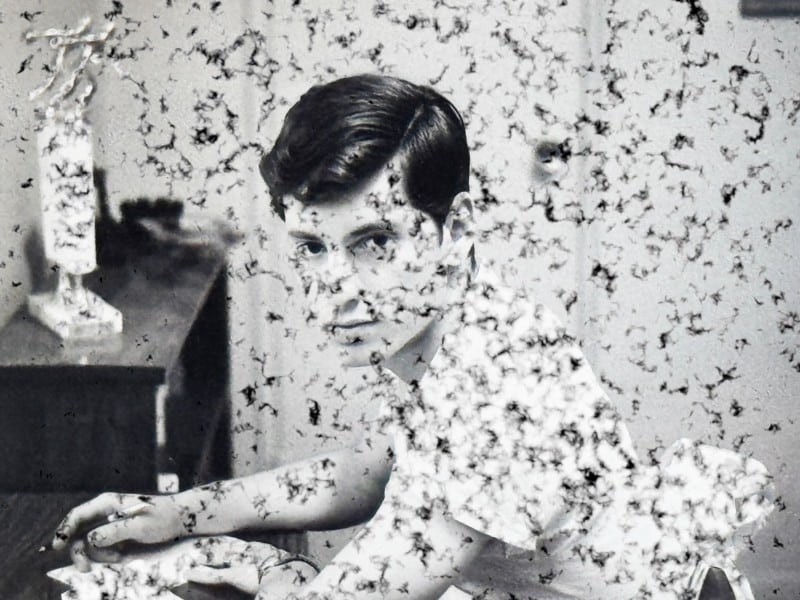

Early in Richard Mosse’s Broken Spectre (2022)—a new 74-minute feature film on a loop in the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (MMoCA)’s main second-floor gallery through February 16, 2025—a fragment of Ennio Morricone’s score plays from the spaghetti Western Once Upon A Time In The West (1968). It is the only deviation from composer Ben Frost’s original haunting sound design and music. Morricone’s leitmotif plays over a diptych of images showing the tranquility of domestic agrarian life in Brazil: a woman cleaning dishes, a dog sleeping under a car, a boy playing with toy farm animals, a man bottle-feeding a calf.

For a few moments with this Brazilian family, the illegal logging, burning, and assembly-line butchering of cattle that constitute the rest of the film seem very far away. Morricone’s score, alongside Trevor Tweeten’s gorgeous cinematography, lulls viewers into a false sense of security through this picturesque frontier life rather than damning portrayals of ecocide.

As Mosse has noted, Broken Spectre is a glorious, epic Western. Cowboys ride on horseback, “untamed” landscapes stretch for miles, and hundreds if not thousands of heads of cattle herd together. Rather than romanticizing and mythologizing this life, Mosse instead presents a revisionist telling. The film celebrates the natural world in all its complex, multihued glory; meditates on the Amazon and its destruction at the hands of the logging, mining, and cattle industries; and offers a plea from the Indigenous Yanomami people themselves for protection and land conservation. Most of all, it is a reminder of the staggering power of cinema as spectacle, deftly moving from the microscopic to the gigantic, all woven together with stories at a human scale.

The scale of Mosse’s artistic scope

Broken Spectre is a profoundly visceral and immediate experience, made possible by its overwhelming size and immersive soundscape (the volume reaches 120dB at times, for which MMoCA provides earplugs). As in his earlier works, Mosse thoughtfully manipulates visual and cinematic language. I first learned of him in the early 2010s via photographs of the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for his project The Enclave (2012-2013). To create surreal images of the DRC’s people and landscape, Mosse used Kodak’s Aerochrome film, which was originally developed in the 1940s for military surveillance. A subsequent project, Incoming (2014-2017), employed a military-grade thermal imaging camera to film refugees arriving in Europe. In both works, Mosse repurposed surveillance tools to highlight rather than perpetuate human suffering: a potent reminder that technology is not inherently belligerent, but can become so through its implementation.

In Broken Spectre, Mosse and Tweeten once again employ nontraditional imaging and presentation techniques, making the familiar alien and exaggerating the expectations of both the Western genre and our traditional understanding of film. Their display format alone—at MMoCA the screen spans 70 feet—underscores this aim to break free from accepted cinematic norms. The width necessitates four projectors and side-by-side screens, a widescreen taken to its extremes. Throughout the film, the visual field is used in a variety of ways: as a diptych, with two wide images placed next to each other (used to stunning effect for many of the cowboy and ranching scenes); as a triptych, often with a black-and-white image at the center flanked by two in color; as a polyptych, with four panels of images; and occasionally as one long, unbroken scene covering the entire projection.

In the latter two instances, Mosse subverts expected visual norms. The use of four distinct images is reserved for the largest scale: sweeping aerial shots in multispectral photography, portraying the vastness of the Amazon and its destruction in hues of brilliant vermillion and coral. These shots also refer to the very imaging techniques mining and logging companies use to exploit the land. Conversely, only when Mosse shows the microscopic does he employ the entire screen as a single field. These scenes are a vibrant tableau of plant and animal life captured via ultraviolet macrophotography. As in his appropriation of military technologies for humanitarian aims, Mosse upends expectations: the enormous landscape is subdivided into distinct frames while the microscopic world is presented as a panorama of monstrous proportions. We see both the vastness of the problems as well as the rich diversity, down to the level of the soil, that the world is losing.

Stunning as these aerial and macrophotography scenes are, the black-and-white scenes that capture the human narrative are most affecting. In these moments, Mosse pushes the formal norms of Westerns to extremes. The typical aspect ratio for a widescreen Western in the genre’s heyday was 2.35:1 (width to height). “We decided to shoot in a wide format referencing the Westerns, combining anamorphic with three-perf 35mm film,” Tweeten writes to Tone Madison via email. The result is an image with an aspect ratio of 3.5:1, a palpable difference that is most notable when Broken Spectre presents two such widescreen images side-by-side. Viewed in the cushion-filled intimacy of MMoCA’s second-floor gallery, the result is the most epic of revisionist Westerns imaginable. It becomes an uncomfortably larger-than-life exploration of humanity’s desire to subjugate, exploit, and ultimately destroy the natural world, along with those who would oppose such actions. There may not be any gunfights, but as Tweeten notes, “the violence and destruction [are] inherent.”

Wisconsin eyes on the Amazon

While the Amazon in Broken Spectre may seem like another universe to Wisconsin viewers, there is a kinship between ecological histories. Ours was once a very different landscape, before European traders and settlers altered it forever via the fur trade, logging, mining, and farming—along with the forced removal and extermination of Native populations.

Wisconsin will never return to those times. The Amazon has not yet reached that irrevocable point, although the window is closing rapidly. “In many ways, it felt like filming the end of the world every day there,” Tweeten further reflects via email. A crucial black-and-white moment in Broken Spectre comes when Adneia, a young Yanomami woman, demands assistance in the face of then-president Jair Bolsonaro’s devastating policies toward the Amazon. Adneia rightfully indicts both the viewer and the documentary team, asking they not just come to film her native home but actually do something to stop the violence against her community at the hand of mining interests. Crucially, this is the only time the film presents an unmediated human voice. Frost’s incredible soundscape, which consistently employs the natural sounds of the Amazon within an electronic score, gives way to roughly five uninterrupted minutes of this woman’s speech, long enough for the image to go dark for a few seconds when the camera needs its film magazine changed.

The film’s closing black-and-white vignette further implicates viewers as voyeurs. Mosse and Tweeten’s camera go through the looking glass of a mirror world reflected in the surface of a river to witness a wild cat wandering along the treed banks. But the lens pulls back to reveal that man is not alone with nature: half a dozen boats surround us, all with tourists and photographers pointing their cameras at the same scene. The journey through the reflected image suggests the impossibility of outsiders truly seeing the Amazon for what it is: a place of both wonder (for its natural beauty) and indifference (to its destruction, in which humans are complicit). All this is underscored by the film returning to its opening: the scene of domestic life, showing people who live this reality. The world’s growing demand for beef is causing families to destroy their forest for more acres of ranching, which is their ironic livelihood. Like all people, they’re deserving of comfort and security, as are the workers facing the dangers of mining and logging.

But why do we tether a person’s ability to make a living to the destruction and extraction of natural resources? And how do we untether from such a system? There are no easy answers to the dilemmas that Mosse presents in Broken Spectre, and his film doesn’t pretend to offer any. But more than anything else I’ve seen in recent memory, the terrifying audiovisual beauty of Broken Spectre conveys the urgency and severity of the problems plaguing the Amazon and the people who live there. It is an unforgettable experience and a clarion call for, at the very least, acknowledging the scope of what we stand to lose.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.