Beltline expansion proposals suggest dead-end logic

“Another lane will fix it” still reigns at WisDOT, but the public is pushing back.

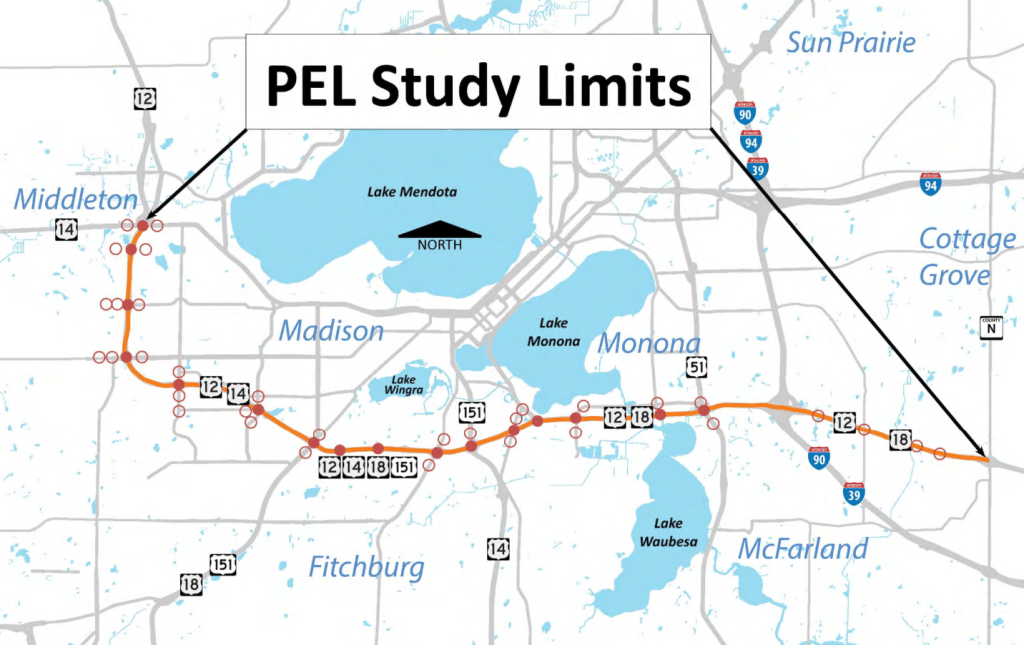

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) is moving ahead with a massive project to address projected transportation issues on 20 miles of the Beltline between West and South Madison. A decades-long Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) study conducted by WisDOT is planned to wrap up by March 2026. A City of Madison project description describes PEL findings that include multiple “strategy packages” proposing projects to deter projected traffic issues like congestion and respond to “long-term transportation needs for the Beltline.”

The Planning and Environment Linkages (PEL) study will guide infrastructure development for projected population growth needs in Madison and Dane County by 2050. The study aims to preliminarily outline “specific improvements, which will ultimately be studied more closely as required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).”

The NEPA studies, which evaluate environmental impact on projects that use federal funds, are scheduled for the “mid to late 2020s,” and will build on the findings and suggested construction strategies initiated by the PEL. WisDOT has suggested fairly benign solutions like “improved local road crossings, bike and pedestrian connections, park and ride options and transit priority improvements.” However, a proposal to offset projected congestion on the Beltline by potentially adding an additional lane is troublesome for the community according to Sierra Club campaign coordinator Cassie Steiner-Bouxa.

“We can anticipate really high costs,” Steiner-Bouxa says. “I don’t know how long it would take, but three miles of expansion in Milwaukee on I-94 is taking eight years of construction. The Beltline proposal is 20 miles.”

Earlier this month, WisDOT asked the public to submit their questions and concerns regarding the PEL study for a virtual public involvement meeting with Jeff Berens, WisDOT project manager, and Jeff Held, a consultant from Strand Associates—an engineering firm that has frequently partnered with the City of Madison and WisDOT.

During a Q&A period, Berens and Held answered questions submitted by the public on the environmental, logistical, and accessible dimensions of this project. Held read aloud a comment from a community member (Held and Berens did not disclose community members’ names) who argued that many states have not seen congestion relief following freeway expansions, and questioned if WisDOT can ensure that trend won’t simply continue on the Beltline if it is expanded. Berens offered a vague response, deferring any definite answer to future NEPA studies that will “reassess the traffic forecasts and consider the growth and development in the area.”

“In almost every case when you add a lane on a highway, traffic congestion is worse within two years of construction,” says Steiner-Bouxa, based on findings by a Transportation for America study. “The decisions that are being made are made with really outdated definitions of what successful transportation looks like. It’s really outdated modeling and data and assumptions that are being used.”

In his response, Berens also acknowledged uncertainty around the induced demand that this proposal will inevitably encourage. This type of artificial demand “means if you build it people will use it, and it becomes busier. When transportation and highways get wider, more people use it and that actually makes conduction worse,” Steiner-Bouxa says. Berens added that the current PEL study does not “do a very good job of considering induced demand.”

Keeping the community in the loop

Beyond the logistical hurdles and excessive expenses, the public aversion toward never-ending traffic expansion is understandable due to the myriad of possible negative environmental impacts. It’s not just exhaust fumes; residents are concerned about littering, noise pollution, and further alienation of the city’s underserved communities.

Another public comment that Held read aloud raised the issue of city ordinances to meet climate goals, and mentioned the Fitchburg council resolution outright opposing any Beltline expansion. When asked how the project plans to coordinate with local governments, the project managers again avoided specificity by deferring to when strategies in the PEL will be revisited and reconsidered to ensure they are NEPA-compliant in consultation with local officials.

But communities actively experiencing the harmful environmental impacts of infrastructural inequality don’t have the luxury of waiting around for those results. Held read aloud another comment by a virtual audience member that asked, “What consideration was made to demographic information and the potential disparities for communities near the Beltline?” The audience member contextualized the issue, citing existing disparities in asthma rates for the communities that reside nearest to the region of the Beltline.

“Highways were very intentionally built in this country to enforce segregation… with a lot of communities of color South and West of the Beltline. We see that in Madison as well,” says Steiner-Bouxa. “This is a literal physical line that makes it more difficult for people who live in those neighborhoods to access other parts of Madison and vice versa.”

Berens and Held claim they are already working with these communities in mind, and mentioned an “indirect and cumulative effects analysis that tries to look at those types of impacts.” This analysis reportedly mapped “three residential impacts” between Middleton and Fitchburg, and a “potential impact to lower-income populations residing in affordable housing along Fish Hatchery Road” was labeled as a “special population impact.” However, these alarming indicators will, again, only be scrutinized once the project is already moving along to the NEPA study stage.

This raises the question: if issues with this purported solution are already springing up, why aren’t community alternatives being taken more seriously while we’re still years away from the start of any actual construction?

Regardless, the community still has time to scrutinize the issue and pressure officials into actually getting creative with their solutions. Madisonians don’t have to fall for the same old “just one more lane” non-answer to optimizing our infrastructure. This is shaping up to be a long-term struggle that will call for sustained involvement and wider community engagement.

“I do think that there’s a lot of leadership locally here, and if there’s an area of state that can stop a harmful highway expansion, I hope it would be Dane County and the Madison area,” says Steiner-Bouxa. “And I think that setting that precedent and local leadership would be huge for the rest of the state.”

You can share your input directly to WisDOT by submitting an online comment form by January 15.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.