As a musician stages his comeback, his accusers ask where the accountability is

Four years after allegations of grooming and sexual misconduct, David Henzie-Skogen is back on the road with Youngblood Brass Band.

Editor’s note: This story discusses allegations of grooming, abuse, and inappropriate sexual behavior with minors. If you or someone you know needs support, please refer to a Google Doc we have compiled of local, state, and national resources.

Musician David Henzie-Skogen vanished from public view in October 2021, after at least a dozen women accused him of sexual misconduct. Alumni of a high-school drum-corps program in Oregon—where Henzie-Skogen was a longtime instructor—came forth with allegations that he had repeatedly groomed and preyed upon underage students over the course of nearly 20 years. Henzie-Skogen was 42 years old at the time the allegations became public.

A group of women teamed up to issue a damning statement, describing a long-running pattern of grooming—which anti-sexual-violence organization RAINN defines as “manipulative behaviors that the abuser uses to gain access to a potential victim, coerce them to agree to the abuse, and reduce the risk of being caught.” They formed group chats to support each other and talk about their experiences. The long-running drum-corps program, Shadow Drum and Bugle Corps, took a hiatus in the wake of the scandal, then announced in December 2022 that it would shut down. (Drum-corps programs are essentially a contemporary twist on traditional marching bands and color guards.) Women who say they’ve experienced sexual misconduct from Henzie-Skogen would occasionally hear rumors about Henzie-Skogen’s whereabouts, but nothing that could be confirmed.

But then Henzie-Skogen surfaced in a new capacity: “Behavioral Technician and Recovery Specialist,” at Seeking Integrity, a Los Angeles-area company that, according to its website, offers treatment for “sex addiction, porn addiction, and paired substance/sex addiction.”

A staff bio page for Henzie-Skogen on Seeking Integrity’s website states that “David is one of the newest additions to the Seeking Integrity family (joining in early 2023), having sought out work in recovery after his own transformative experience in residential treatment and subsequent involvement in the Los Angeles recovery community.” Metadata on the page suggests it was initially published in December 2023. Most sources who spoke with Tone Madison for this story didn’t see it until spring 2024. Versions of the staff bio page archived and screenshotted since spring 2024 show that language and job titles—like “Aftercare Coordinator”—in the bio have changed over time.

Now, Henzie-Skogen is returning to the public eye as a musician. Youngblood Brass Band, which he co-founded in 1998, is currently on a tour of the UK and Europe this fall, and the band has confirmed to Tone Madison that Henzie-Skogen is part of the tour. It kicked off with an October 27 show at the Village Underground in London, and is set to end with a November 20 “educational workshop” at the Conservatoire de Marquette-lez-Lille in Lille, France.

Several of Henzie-Skogen’s accusers are asking why he embarked on this new chapter before publicly acknowledging or responding to the accusations against him. They’re also questioning how he managed to gain a professional role in behavioral health within less than two years of the allegations becoming public.

“We kind of assumed that because it got so much news coverage that anytime you typed in, you know, ‘David Henzie,’ Google finished with like ‘Skogen grooming’ or whatever,” says one of Henzie-Skogen’s former students, who, like several people quoted in this story, asked that their name not be published due to concerns about privacy and retaliation. “We were like, ‘okay, he’s never gonna get a job again, in this regard.'”

“I’m very surprised that any organization would hire someone and put them that publicly on their page and promote them when they have such history and that is publicly available as well,” says another of Henzie-Skogen’s accusers.

In an emailed response from a shared band email account in September 2025, Youngblood Brass Band told Tone Madison: “We’ve seen the daily work Dave has done the last four years in therapy, accountability, service, and amends, and also professionally, and believe in it. We support his position on this tour. Dave now works at an intimacy/attachment treatment center. You can read his bio, which summarizes some of the work he has done over the past four years, here,” with a link to the Seeking Integrity staff bio page mentioned above. The statement was signed by “YBB” and not an individual person.

A few days later, Henzie-Skogen sent Tone Madison a link to a statement he posted online, dated September 18. This marks his first public acknowledgement of the allegations against him, nearly four years after they became public. The six-paragraph statement begins:

The following is a statement of accountability; people have questions, and I am going to do my best to clarify and take responsibility below.

I had several problematic relationships with alumni of the program at which I taught in which I caused harm. In some of these relationships there was personal and emotional communication while these women were students. During their time as students, these relationships were not physical or sexual and there was no sexual assault, criminality, or explicit communication. However, in two instances (2008 and 2013) a physical relationship began immediately following graduation from the program. In other instances relationships began months or years later. Some of these relationships were physical, and some were not. I never intended harm or was intentionally manipulative, however, I recognize that I disregarded my responsibility and exploited my position of authority as an educator, and that my impact was harmful. I have spent the past four years reckoning with this and focusing on recovery, therapy, offering amends, and trying to make it right by committing to living in integrity and service. I have reached out personally or via my restorative coach to many people to offer these amends/restorative practices, but know I do not determine what healing means for anyone else.

The statement goes on to acknowledge other “unhealthy relationships,” discuss his recovery process, and address his public silence up to this point. Henzie-Skogen writes that he has received “hateful, threatening, and abusive communication,” and that his family, colleagues, and friends have as well.

Tone Madison also sent Henzie-Skogen a detailed list of questions about the allegations in this story. He has not responded.

While the statement offers apologies and admits to a range of inappropriate behaviors, it doesn’t match the full extent of what Henzie-Skogen’s accusers have been saying all along. In their October 2021 victim statement, a dozen women wrote that “The relationships David cultivated with us were predatory, sexual, and abusive.” As these women began to contact each other and share their experiences, they say they saw patterns repeating over and over again. “David’s actions and words were all premeditated, calculated and exploitative,” they wrote.

More women have come forward since then, joining an informal community of group chats. Not all of them have chosen to speak out publicly, so the total number of Henzie-Skogen’s accusers remains unknown. Henzie-Skogen’s statement acknowledges harm, but repeatedly describes that harm as unintentional.

The “amends” part is news to every single one of the women who have spoken with Tone Madison over the past four years about the misconduct they say they experienced from Henzie-Skogen. Multiple women have consistently, steadfastly, in repeated interviews from fall 2021 to fall 2025, said that they’ve never seen any statement or communication from Henzie-Skogen that would resemble a meaningful effort to make amends. Asked about the band’s email statement supporting Henzie-Skogen’s renewed involvement, the women cited in this story all stood by their previous accounts. Henzie-Skogen did attempt to reach out to at least one of them through an intermediary, but she found the attempt unwelcome, as detailed later in this story.

On top of that, several male Shadow alums heard about the emailed statement from the band and reached out to Tone Madison. (To the best of our knowledge, all of Henzie-Skogen’s accusers are women.) They looked up to Henzie-Skogen as teenagers, and then as men. They speak with a palpable fury about the idea that Henzie-Skogen was preying on their female friends while they enjoyed the benefits of a positive, if intense, musical education. They all say that Henzie-Skogen has never reached out to offer the kind of repair and apology the tight-knit Shadow community deserves. “I have heard nothing from Dave to make any sort of amends,” says one male Shadow alum, who asked not to be named in this story. “I personally feel like if David was making amends and being accountable, I would have heard from him,” adds Chris Di Bernardo, another Shadow alum who went on to play with Henzie-Skogen in Mama Digdown’s Brass Band.

Henzie-Skogen was an outsized presence in Madison’s music community for more than 20 years, leading the internationally touring Youngblood Brass Band as its drummer/MC, co-founding the instrumental rock band Cougar, and releasing other artists’ recordings through his Layered Music label. His new professional profile and recovery narrative underscore the fact that his accusers are still waiting for a real sense of accountability, four years after the allegations against Henzie-Skogen first became public. These women also question the timing of Henzie-Skogen’s statement, posted more than a month after Youngblood Brass Band announced its tour and nearly two years after his Seeking Integrity bio went online.

“It’s disturbing, and it’s, for me, a stepping stone for him to reintegrate himself into the Madison community again, which I just don’t want to see happen,” says yet another accuser of Henzie-Skogen’s re-emergence as a behavioral health professional. “It would really freak me out, honestly.”

Allegations in Shadow and beyond

Most of the public discussion and media coverage up to this point has focused on allegations that Henzie-Skogen struck up inappropriate relationships with underage students, then ended up pursuing sexual relationships with some of them after they turned 18. Shadow leadership have also claimed that Henzie-Skogen had a physical relationship with one student when she was still 17. But the Oregon Police Department and Dane County District Attorney Ismael Ozanne decided in July 2022 that they would not pursue criminal charges against Henzie-Skogen.

Shadow fired Henzie-Skogen in May 2021. At the time, Shadow’s board had heard of only one allegation of an inappropriate relationship between Henzie-Skogen as a student—and that was all Henzie-Skogen had acknowledged, then-president Ken McGlauchlen and former executive director Rebecca Compton-Allen told Tone Madison in a previous story. Shadow initially decided not to make a public statement, believing this to be a single isolated incident. But more women came forward with accusations over the following months, prompting Shadow leadership to investigate further and issue a public statement in the first week of October 2021.

Over the course of the four years since the allegations became public, Tone Madison conducted interviews with women who accuse Henzie-Skogen of sexual misconduct, some of whom were never involved with Shadow. One tells Tone Madison that Henzie-Skogen began pursuing her via Instagram when she was 16. Another met Henzie-Skogen via a dating app when she was 20, and says the two developed a relationship in which he would record and share explicit material without her knowledge or consent.

About a week after the grooming allegations became public in October 2021, several bands and musicians affiliated with Henzie-Skogen—including Youngblood Brass Band and Mama Digdown’s Brass Band—announced they were cutting ties. Their statements condemned his actions, voiced support for the women who came forward, and called for accountability. (Some of these statements were posted on Twitter accounts that have since been deactivated.) Since then, there has been little public discussion about it in Madison’s music community or cultural press. (For instance, Madison Magazine, Isthmus, and The Capital Times all ran feature articles about Mama Digdown’s 30th anniversary in 2023 without mentioning Henzie-Skogen, who played with the band for more than a decade)

It also remains unclear how many people close to Henzie-Skogen in the local music community knew about the extent of his behavior. A July 2022 story in the Wisconsin State Journal notes the following, citing documents from an Oregon Police Department investigation:

Interviews and police documents indicate that members of Youngblood Brass Band knew about Henzie-Skogen’s involvement with young girls before the accusations surfaced.

Bandmates knew David “liked younger girls” but were unaware of the extent of his behavior at Shadow Drum and Bugle Corps, one member of the band said. Two other members of the band did not respond to a request for comment.

Lauren, who asked to be identified by first name only, met Henzie-Skogen through a dating app in 2013, when she was 20 years old. She had gone to high school in Oregon, but hadn’t participated in Shadow.

“The first time he hung out with me, he admitted that he didn’t know me from Oregon but saw that on my dating profile and wished he knew me from high school,” Lauren recalls. The two developed a sexual relationship within a couple of months.

“So much of what I’m realizing now is the power dynamic going on that I wasn’t aware [of]… when you’re technically a legal adult but you don’t have much of a frame of reference,” she says.

Lauren says that early in the relationship Henzie-Skogen “sent me a video of us having sex that I did not know that he took.” She says that Henzie-Skogen would use videos of the two having sex as “leverage” to get her to send more explicit material to him, and to have further sexual encounters with him. (Henzie-Skogen did not respond to a list of questions that detailed specific allegations, including this one.)

According to Lauren, Henzie-Skogen continued to use explicit photos and videos in this way, even showing her explicit photos of another woman he was involved with. She says this dynamic continued into 2015, when she began trying to break contact.

In 2016 and 2017, she says Henzie-Skogen continued to send her unsolicited explicit photos, disrupting her efforts to move on. This created problems in a newer, more serious relationship Lauren had begun. “[Henzie-Skogen] would show up at my [apartment] at that point… when I was there, and then sometimes when I wasn’t there, and occasionally the guy I was seeing would be at my apartment and just see him come up to the door and sit there for a while,” she says. For a time, she moved away from the Madison area and stopped responding to Henzie-Skogen’s messages entirely.

“There was no clean end… I was probably still getting messages in early 2018 that were him fishing for some sort of contact,” Lauren says.

Tone Madison reached out to Henzie-Skogen with a thorough list of questions based on our reporting but did not receive a response.

Like other women interviewed for this story, Lauren has spent several years in therapy trying to process her experiences. Seeing Henzie-Skogen reemerge in his new role at Seeking Integrity hasn’t helped.

“It feels like ages dealing with it,” Lauren told Tone Madison in March 2024. “I’ve just kind of started to move past it and now I’m getting pulled back into it again.”

Reading about Henzie-Skogen’s recovery arc on his Seeking Integrity profile page, Lauren came away angry and suspicious. “In most recovery methods that are out there, whether they’re 12-step-based or whatever, there is an acknowledgement portion, and where the hell was that?” she asks. “I just don’t believe in recovery without that.”

For Lauren, that step would need to come down to Henzie-Skogen making “some acknowledgement of what he did. I mean, honestly, no apology or whatever is ever going to actually make up for any of it, and that’s not the goal,” she says. “But some acknowledgement would be helpful, that this did happen and he did hurt people irrevocably, and that he acknowledges he did it to the public.”

Another woman who spoke with Tone Madison says that she wasn’t involved in Shadow, but met Henzie-Skogen when she was a teenager. “I was involved in my high school marching and jazz bands and David found me through Instagram when I was 16,” she says. This source, who asked not to be named in this story, took part in a group statement of women calling out Henzie-Skogen in fall 2021.

“We want people to know that he was a master manipulator,” she told Tone Madison in an email in 2021. “We were kids who idolized him and he told us how mature and special we were. We are upset that his adult peers at the time never acted on their observations of inappropriate behavior. He had everyone wrapped around his finger.”

Before seeing Henzie-Skogen’s profile on the Seeking Integrity site in spring 2024, she didn’t know anything about his whereabouts or activities after his firing. She also says she has not heard of Henzie-Skogen reaching out to other accusers she has been in touch with.

“I wouldn’t have wanted to be [contacted],” she says. “I feel like it’s pretty empty, saving face.”

After learning of Henzie-Skogen’s role at Seeking Integrity, she summed up the spirit of conversations she’d been having with other women who accuse him of sexual misconduct: “What the fuck? This is really frustrating. The absolute gall of him.”

She: “So he was in, what? Recovery for a year? And now all of a sudden, he’s qualified to tell other people? That’s bullshit,” she says. “You can’t be a pedophile since the 2000s and now, [say] ‘Oh, I’m cured, and now I can tell everyone else how to be better.’ That’s just so classic David, is wanting to get into people’s heads, telling them how to live better lives and validating feelings and just form a close bond. It feels very much like a power thing once again… he’s always putting himself in this position of ‘I’m good and I can tell other people how to be good.’ That pissed me off. When I saw that—there’s no way this is valid.”

This woman and others who spoke with Tone Madison underscored that each new development is particularly upsetting for people who are still recovering from their experiences with Henzie-Skogen.

“Honestly, I still get a lump in my throat every time I see something about him,” the woman says. “My stomach drops, because it is still recent, and it’s hard to know how intensely you’ve been manipulated and taken advantage of. No matter how much therapy I can go through, I don’t think there’s any peace that’s going to come from it. It’ll just be, ‘Oh now I don’t want to punch a wall anymore,’ or something.”

“For those of us that legitimately were children, it’s stinging a little bit more,” she says. “Not to invalidate anyone’s experience… I think about it every fucking day, and it hurts.”

She adds: “[Henzie-Skogen] used music education as a pool of prey.”

Steph, another Shadow alum, began participating in the drum-corps program in 2008, when she was 13, alongside her older brother. She never developed a physical relationship with Henzie-Skogen, but also recalls Henzie-Skogen making inappropriate advances. Steph asked that only her first name be used in this story.

“It started with, like, first of all, at-home drum lessons in his home, and now that I look back I’m like, what, why was that happening… when he was affiliated with a high school that had the facilities to provide these lessons?” Steph asks.

Over time, she says, Henzie-Skogen began contacting her through Facebook and the two frequently messaged back and forth. They discussed “personal life issues and things I was going through as an angsty 8th grader,” she says. “At some point, he initiated discussing sexual fantasies he had with me… One of the fantasies involved me going to a Youngblood concert that was at the High Noon Saloon, and my parents had to drive me because I was not old enough to drive.”

Like other women who say they experienced misconduct from Henzie-Skogen, Steph says it took her a long time to understand the experience and the impact it had on her. “I reciprocated,” she says, recalling her relationship with Henzie-Skogen. “I was a kid and we really idolized this guy, and I felt like I was special and what we had was special.”

Steph lost contact with Henzie-Skogen after graduating high school, though he would occasionally try to get in touch. She says Henzie-Skogen once contacted her through a dating app to ask how her endeavors were going, though she didn’t respond, and that he contacted her to ask her about an instructor at the college she attended. “It seemed like he tried to keep his claws in us, or in me,” Steph says.

In the ensuing years, she tried to put the experience with Henzie-Skogen behind her. But different conversations and experiences kept dredging up the memories. Steph recalls an incident in 2017 when she marched with the Milwaukee Bucks’ drumline.

“We went out for beers after a game or a rehearsal. There were members who had marched for a program that had marched against Oregon and one of them had actually instructed against Dave,” she says. “Someone brought up, like, ‘Yeah, David seemed to have a weird relationship with you guys’… and I just started crying at this bar. It was like the emotions didn’t have time to process.”

Until Shadow issued an announcement about Henzie-Skogen’s firing in 2021, Steph didn’t think she would have any recourse, because of the culture of the drum-corps world and the position Henzie-Skogen occupied within it. “Anyone who interacted with Dave put him on a pedestal,” she says. Steph says she would welcome an apology from Henzie-Skogen.

She wasn’t aware of Henzie-Skogen’s recent activities until Tone Madison contacted her for comment for this story in March 2024.

“I was a little bit surprised, given that like, thanks to [media coverage of the allegations from 2021], if you Google his name, really everything that comes up is all of his terrible predatory behavior,” she says. “I was pretty surprised that a place that takes people in such a vulnerable time—people admitting to an addiction and to illness—would want someone with a history like that associated with their job or their business, but I guess that’s a different world than what I’m used to.”

Steph believes Seeking Integrity is “playing with fire” by placing Henzie-Skogen in an environment where vulnerable people seek help for behavioral health problems, given his past behavior and his ability to manipulate even the adults in his orbit.

“My second reaction was this very guttural anger that he is profiting off of being a sexual predator,” she says. “I just can’t put it any other way. He is paying his bills off of saying that he healed after he groomed—I don’t remember how many women the last article stated… I feel an insane rage about that.”

“There’s nothing to restore”

The women interviewed for this story all pointed out that accountability and making amends are crucial concepts in the world of recovery, and yet they’ve seen little in the way of accountability for Henzie-Skogen. Aside from the September 18 statement, he’s never issued a public apology or made any sort of public comment addressing the allegations against him. From the viewpoint of most people, including accusers, it was a dissonant sequence: the allegations come out, the accused drops off the map, then a while later, suddenly he’s back out there, working in some kind of treatment capacity, and then playing music again.

It’s not even clear what Henzie-Skogen acknowledges having done, or whether or not he disputes any of the allegations against him. Henzie-Skogen’s bio on the Seeking Integrity website states that his recovery process involved “a program focused on addressing unhealthy attachment, disordered intimacy, limerence, and validation-seeking.” (“Limerence” is a term for “an involuntary attachment to another person… that takes on an obsessive quality,” as a 2024 Cleveland Clinic blog post explains.) The bio sticks to these broad terms and doesn’t mention specific behaviors. Nor does it mention the involvement of underage victims.

One of Henzie-Skogen’s accusers, who knew Henzie-Skogen through Shadow, says an intermediary named Risdon Roberts reached out to her on behalf of Henzie-Skogen in January 2024, asking her to be involved in a restorative process with Henzie-Skogen. (This woman asked not to be named in this story.) Roberts’ website describes her as “an intimacy, consent, & sex expert” who also works as an intimacy coordinator for movies and TV shows. Roberts’ website says she “received training as both a Consent Educator and Intimacy Coordinator” and is “currently in school pursuing a graduate level degree in sex and psychology.”

“This person who reached out to me identifies themselves as a ‘restorative practices facilitator’—that’s in quotes—and said they’re reaching out on behalf of a client who was working through an accountability process and wanted to see if I was interested in participating in some sort of restorative conversation,” the woman Roberts contacted on Henzie-Skogen’s behalf says. “It says ‘this practice is intended to address any harm you have experienced and give you an opportunity to be heard in a safe and mediated environment. So please reach out to me if you’d like more information on restorative practices,’ and [they also] provided their contact information and various things.”

She says that after Henzie-Skogen was fired from Shadow, program leadership directed him not to contact her. She says the attempt at contact felt “menacing,” regardless of what the intent may have been. (Tone Madison has reviewed screenshots of the text messages. Reached for comment for this story, Roberts declined to discuss her work with Henzie-Skogen, citing client confidentiality, but did tell Tone Madison she is a “Restorative Justice Conference Facilitator.”)

“What I made of his attempt to reach out to me was that it was completely inappropriate,” the accuser contacted by Roberts says. “Also, if there were to be any sort of amends between people in general, I just don’t think that there’s anything to restore. We’re not in contact. We’re not going to be. We’re not going to be friends. I don’t know if he’s, quite—I don’t think he’s quite grasped the magnitude of the impact this has had on people, despite all of our voices in the media. I know a few of us have talked to certain reporters for stories, and we co-authored a statement that had some pretty direct and harsh language in it to try to project our discontent or explain how this has affected us.”

“It took me a few weeks, a couple weeks, to respond. I was really, really pissed off about it, especially because this person wasn’t licensed at all, and the only reason [Roberts] had my phone number is because he ostensibly gave it to her,” she says. “His number’s blocked on my phone, so there would be no way for him to directly contact me.”

For this woman, the idea of going through a restorative process with Henzie-Skogen is so galling because “it was never an equal relationship. It was not a friendship… because he had an end goal in mind,” she says. “And also, the organization that he partially helmed for a really long time doesn’t exist anymore. Shadow doesn’t exist anymore. So there’s nothing to restore. There’s no friendship to restore. There’s no legacy to restore. Even if there were personal feelings that I could let go of via some sort of conversation with him, I can’t forgive him for myself, but I can’t forgive him for everyone else either.”

She joined Shadow Indoor Percussion in fall 2009, at age 15. She was working on the program’s stage crew, not playing an instrument, and a group of friends from her high school class worked alongside her. She met Henzie-Skogen that year. She was still 15 in March 2010, when she recalls receiving her first Facebook message from Henzie-Skogen. “It was just kind of a playful ‘Hi, how’s it going’ message… he kind of gave me a teasing nickname, stuff like that,” she recalls.

She joined the Shadow Armada summer program in summer 2010, playing flute. She played in the summer program every summer through 2013, and participated in the indoor program again in 2012 and 2013. Throughout all this, the Facebook conversations with Henzie-Skogen continued.

“We got really close, I would say. He kept messaging me. It was very much him initiating…I was really young and I wasn’t about to send a message to an adult that I didn’t know very well,” she says, but Henzie-Skogen kept reaching out. She looked forward to these conversations, because they made her feel like an adult was taking her seriously, even recommending books, movies, and music. He would send her unmastered tracks for Youngblood Brass Band’s then-in-the-works new album and ask her for feedback.

“It was a very big cultural exchange, something I hadn’t experienced before. He made me feel really smart, very special, like I was especially smart or especially clever. We would talk a lot, especially when he was on tour with Youngblood Brass Band,” she says. When Youngblood toured Europe, she would carry on text conversations while she was in class and Henzie-Skogen was killing time before shows. Other conversations would go late into the night, until 2 a.m. or so, even when she had school the next day. “He was my confidant, in a way,” she says. “We racked up truly an amazing amount of messages.”

Over time, she says, Henzie-Skogen began talking more about attraction and sex, dropping hints in the form of acronyms, and made suggestions about hanging out in person. “It was a real shock to me,” she says. “I didn’t date anybody in school. I didn’t really have a framework for understanding what a romantic or sexual relationship was like. I didn’t feel the same way he did. I was super enormously green, even for my age, but he knew that too.” She says she dealt with this confusion—again, while she was still in high school—by convincing herself, or letting Henzie-Skogen convince her, that this was just something adults do, and that an emotional relationship should naturally lead to a physical relationship.

“That’s what it became the day after the program was over,” she says. The two had a physical relationship for about two years. She broke it off in 2015; she’d begun attending college out of town, and would still spend time with Henzie-Skogen when visiting home in the Madison area. “I was really upset all the time and I wasn’t getting what I needed from a relationship. It was really a shell of one, and I was just beginning to feel really bad about it,” she says. “I was smitten with him, truly. I was in love, and I told him that, and then I didn’t get a response. I told him in person but he completely shut off.”

Still, the two remained in contact until 2021. The woman even served as a committee chair on Shadow’s board for a time, sometimes collaborating with Henzie-Skogen on the program’s social media and press releases. She recalls being in a Zoom meeting in which Shadow board members discussed proposals for protecting students from sexual misconduct, bullying, and discrimination. Everyone in the meeting agreed that the program should create a safe reporting structure for students with concerns—so that they wouldn’t have to confront their teachers or program leadership in person if they didn’t want to. “I saw that and it just triggered a whole tsunami of, ‘I didn’t have this when I was younger and I’m on the other side of it now… and I have to do something now,” she remembers. She got nauseous and left the meeting.

Shadow’s former executive director, Rebecca Compton-Allen, in a fall 2024 email exchange with Tone Madison, stresses the ongoing need for accountability.

“What I can say with complete conviction is that no one in our community, especially the women that came forward, has any obligation to feel any sense of forgiveness or relief from David’s work [in recovery and behavioral health], and that any discomfort with his position is completely valid given his misuse of power,” Compton-Allen wrote in a fall 2024 emailed statement to Tone Madison. “Grief, anger, and healing are such personal journeys for everyone affected, including myself.”

One theme that comes up over and over again in talking with Henzie-Skogen’s accusers is that they are dealing with this in terms of long-term, maybe life-long, impact.

“It’s important for people to know how this affects a young person into their adulthood,” says one of the Shadow alums who accuses Henzie-Skogen of misconduct. “When something happens to you at a really young age, a really formative age, it can mess with you until you deal with it.”

The statement Henzie-Skogen posted in September 2025 only added to the accusers’ sense of ongoing, exhausting vigilance. Several told Tone Madison they found the statement minimizing and misleading.

“I’m pretty sickened by this. Aside from much of it being lies and basically calling us liars, it uses language that diminishes his behavior,” one of the women says of the statement. “Referring to students as alumni evokes an image of adult women and not middle school and high school girls. Though most of his victims were a part of Shadow, I think by acknowledging only those ‘problematic relationships’ he is trying to erase the pervasiveness of his predation that led him to Instagram messaging me at 16. We already know his treatment center is dodgy, and I don’t believe therapy for ‘disordered relationship to intimacy, romantic intrigue, and entitlement’ fixes a pedophile… I also believe that since he has never publicly addressed what he did, this statement only acts to regain control of the narrative. We hoped David would just disappear, but he wants to be back in the spotlight with the attention ever on him.”

“I found the statement rote, lacking in contrition, and unclear with regard to what he actually did, what he is sorry for, and who he is apologizing to,” says another woman who says she experienced misconduct from Henzie-Skogen. “Some of it is just lies. But ultimately, I think it’s more about what a community accepts. Does a vague explanation of disordered intimacy and a weak ‘I’m sorry’ win him back his position as a musician and educator, the authority of which he used to groom kids? I hope not.”

“David really minimizes the damage he caused and really focuses on what he has done for personal reconciliation, not making amends towards others he harmed,” Di Bernardo says. “It’s also frustrating that Youngblood largely just ignored the whole issue without really releasing a statement [about Henzie-Skogen rejoining the band], and are now just back to business as usual without really letting their fans know what happened in 2021, or that David re-entered the band.”

An intense and insular culture

Shadow alums describe drum corps as a world of fierce dedication and camaraderie, one that’s hard for those outside it to understand. “Drum corps is like a religious experience,” she says. “Shows are like a cross between an opera and a military offensive,” one alum says. She believes this insular culture enabled Henzie-Skogen to prey on students year after year. She says that as she put high school behind her and began to process her experiences, her bonds with other drum-corps alums both made it difficult to speak out, and eventually helped her do so.

“Because I was so emotionally connected to this group, I waited a long time to talk about what David did,” she says. “I couldn’t imagine being the catalyst for the death of Shadow. I knew the program was very vulnerable as it transitioned from a marching band to a drum corps. I desperately wanted to protect it, and unfortunately that meant I was shielding David from consequences as well.”

Individual drum-corps programs, and the drum-corps world as a whole, have often failed to protect students from various forms of misconduct. Drum Corps International (DCI), the nationwide governing body for these programs, has developed a system for ethics and compliance reporting. In 2018, DCI rolled out a new set of policies aimed at cracking down on misconduct and discrimination of various kinds, with a particular focus on “sexual or romantic relationships between instructors and performers.” This came in the wake of a 2018 Philadelphia Inquirer investigation, which found that “nearly a dozen cases over the last decade in which teachers who had been disciplined for misconduct with students went on to work in drum corps as instructors, administrators, or judges.” In a 2019 follow-up, the Inquirer characterized DCI’s response to multiple allegations and complaints as “sluggish.” (DCI did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.)

After investigating allegations about Henzie-Skogen’s conduct, Shadow leadership reported him to DCI. This can serve as a way to blackball instructors found to have violated DCI rules and prevent them from getting jobs with other drum-corps programs. But there isn’t much of an enforcement mechanism for this, and it does nothing to prevent such instructors from getting hired in other fields—even when their jobs might involve direct interaction with minors or other vulnerable groups. There are still many practical barriers for people looking to report misconduct, and a lack of long-term follow-up support for survivors.

Rand Clayton, a drum-corps alum based in Ontario, Canada, co-founded the Marching Arts Access, Safety, and Inclusion Network (MAASIN) in an effort to address these gaps, and serves as the non-profit organization’s managing director. Clayton holds a masters in social work, has worked as a counselor for sexual assault survivors, and is currently pursuing their PhD in social work at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Clayton has no connection to Henzie-Skogen or Shadow, and focused their comments on the systemic problems of the drum-corps world writ large.

“We hit 2020, the drum corps season was canceled, and everybody took a step back and really thought about the activity and the things they’ve experienced, and the kind of cultures they’ve been part of for the first time,” Clayton says. “And a lot of people were like, ‘Wow, actually, this is really not okay. The kind of stuff I’ve been subject to is not okay, especially in a youth organization. What do we want to do about this?'”

Much of MAASIN’s work takes the form of free educational materials and resources, including training workshops on subjects ranging from disability inclusion to the safety of transgender students. The organization will also customize workshops and materials to meet the specific needs of different drum-corps programs facing different issues.

“So for example, we’ve actually been working with the Cal band for several years,” Clayton says. “We give them a disability allyship workshop every year to help make sure that the band is staying inclusive, which is really nice.”

MAASIN has also developed a whistleblower support program, which helps people with the practical work and emotional burdens of reporting misconduct they’ve experienced or witnessed. Whistleblowers can reach MAASIN’s team via support@maasin.net.

“DCI itself does have a whistleblower portal, but you should usually go through your individual corps’ whistleblower portal first,” Clayton says. “Some organizations are very good and compassionate at dealing with survivors of sexual assault or anybody who’s speaking out against bigotry, anything like that, and some organizations are not. And so where we come in is if you want to report to your organization that you are uncomfortable reporting, not anonymously, or if you just want a friend throughout the process, or somebody who’s able to gather all the info for you and kind of take some of the like load off… we’ll do that.”

Crucially, MAASIN’s whistleblower support teams can serve as intermediaries for whistleblowers who don’t want to reveal their identities to their drum-corps programs. This can make it less daunting to speak up, and harder for complaints to fall through the cracks.

“Unless you choose to be named, it is very difficult for the organization to follow up,” Clayton says. “So if you submit your report, but you submit it anonymously, they can’t follow up with you, and then less can be done… but if you submit it through us, they’re able to follow up with us, so then we can follow up with you and ask, ‘Hey, are you comfortable stepping forward?’ Now I find that a lot of people just need someone to help them take the first couple steps, and then they’re more comfortable speaking to the organization about their experiences so that the issue can be dealt with.”

Dozens of individual programs around the U.S. and Canada belong to Drum Corps International. Not all of them have the resources, infrastructure, or expertise to handle cases of serious misconduct. “The entire reason MAASIN was created is because there was a serious lack of any sort of support for survivors, [and] there’s basically no standardization,” Clayton says. “The response you’re going to get at any corps is kind of different depending on just who works there, how much support they have as an organization—are they a larger, more well-resourced organization, or are they a smaller, not-as-well-resourced organization? Which is really hard, because there’s a lot of organizations that are genuinely trying very hard to do good work and make sure they are doing right by everybody, but maybe they don’t have a lot of resources at their disposal, which makes things a lot more challenging.”

Another crucial piece that’s not standardized or centralized, Clayton says, is the follow-up work of keeping tabs on instructors who’ve been fired for misconduct.

“There have been times where I’ve reported the same person to, like, three corps… That’s so frustrating for everybody involved,” they say. MAASIN keeps records of all the cases it handles and, depending on what whistleblowers are comfortable with, will contact organizations that hire problematic instructors. It’s hard to keep them out for good.

“Very few people actually leave the activity,” Clayton adds. “The thing is, if you get booted from one corps, or people find out that you’re doing gross things to students or anything, there’s a lot of people in the activity who are still enablers, who think that, ‘Oh, it’s not actually inappropriate’ or ‘Oh, if they’re over 18, then it’s totally fine,’ even though, in most states that’s still illegal, because that’s a coach relationship.”

Like just about every drum-corps alum interviewed for this story, Clayton points to the culture of drum corps, and its heavy emphasis on loyalty, as a profound obstacle. Students who’ve experienced or witnessed misconduct are often hesitant to speak out, because they fear they’ll simply be dismissed as troublemakers, be ostracized, or even be wrongfully blamed if their program eventually shuts down. That last one is more palpable than ever. Clayton says that dozens of drum-corps programs have folded over the past few years. More often than not, programs shut down because of the burdens of getting through the COVID-19 pandemic, paired with the financial strain of the sport’s high operating costs. “It’s like $5,000-plus to march a student for the summer,” Clayton estimates. Even with all those practical challenges looming over these programs, it’s easy to see how whistleblowers can become scapegoats.

In the case of Shadow, Compton-Allen says that the Henzie-Skogen scandal was a major contributing factor, but not the only one. “Shadow made it through the pandemic with some funds left, a growing board of directors, and a full team of eager staff, which was an enormous feat for such a small corps,” Compton-Allen says. “However, when I left to take another job, there was no one left with the history of leadership with the organization, time, or passion to support its continued existence. That, paired with knowing the enormous pain that the Shadow community had endured, made the choice to discontinue the program a difficult but natural choice for the board members.”

Clayton says the culture of the drum-corps world is gradually becoming more open to feedback, criticism, and frank accounts of students or alums who want to share their painful experiences. But there’s still a lot of work to do.

“I’d actually really say that the way that abuse in drum corps works is very similar to, historically, the way that abuse in the military has kind of been treated, which makes a lot of sense, [because] drum corps does have military roots… as a recreational activity restarted when returning veterans came home, started these programs in their communities to teach youth skills, about music and character, instill military values in them, do that kind of stuff,” Clayton says.

One gap that, Clayton admits, even MAASIN can’t fill is the need for survivors to have access to long-term support. Clayton can help people track down sliding-scale therapy and other resources, but knows that’s not a substitute for a robust support infrastructure.

“I’d like to see organizations do more for survivors in the aftermath, and remember that the issue for [a drum-corps organization] will be legally over once they’ve legally dealt with it, but that survivor is going to have to live with that for the rest of their life, and we should do more as a community to help them,” they say.

Clayton adds: “One of the things that really grinds my gears about when people are handling cases of sexual assault is a lot of corps are very good at dealing with it from a liability perspective—they’ll do everything they need to not legally cause problems for themselves, which I do respect… However, this means that a lot of the time, corps end up looking at the survivor just as a liability or a problem to be solved, which is not fair. My hope is that corps start thinking about this at a cultural level: How do we make it so that this kind of behavior is unacceptable in our culture and not just treat it as ‘Oh, there’s just a series of bad people who do this thing’? How do we look at this so that every survivor is not just looked at as a liability, but every survivor should be met with compassion in the reporting process?”

Unclear qualifications

Tone Madison has been unable to locate any indication that Henzie-Skogen has a previous professional background or training in behavioral health. (Tone Madison asked Henzie-Skogen about his qualifications in an email but did not receive a response.) It’s not clear whether he has gained any formal training or certification since 2021. His bio on the Seeking Integrity website doesn’t cite any formal credentials. (Several other staff members at the organization list their formal credentials in their bios, some with California licensure numbers that patients can easily look up online through the state’s Board of Behavioral Sciences.) In fact, he likely could not have gained any in such a short time, and the job titles listed for him are not strictly protected by laws or regulations.

Various state laws forbid someone without specific qualifications from practicing professionally as a social worker or psychologist. But it’s essentially perfectly legal for just about anyone to call themselves a Behavioral Technician, Recovery Specialist, or Aftercare Coordinator.

“This guy can call himself whatever he wants and his job can call him whatever he wants as long as it’s not a legally protected title,” says Bruce Thyer, a professional at Florida State University’s College of Social Work. Much of Thyer’s published research centers around education and professional standards in the behavioral health field. He is the co-author, with Monica G. Pignotti, of the 2015 book Science And Pseudoscience In Social Work Practice. Thyer offers “peer counselor” as another example of a professional title that anyone could legally adopt, even with no real qualifications.

A licensed therapist or counselor, as sanctioned by various regulatory agencies and professional organizations, may have any of a few different degrees and credentials, from a master’s in social work (MSW) to a full-fledged medical school degree. They may be a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW), a Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor (LPCC), a psychiatrist with an MD, or a psychologist with a PhD, to name some of the more common and accepted career paths. They generally all have to spend thousands of hours working under supervision before practicing on their own, on top of earning their degrees. It takes longer to become a practicing psychiatrist or psychologist than to become an LCSW or LPCC.

If, as the Seeking Integrity site states, Henzie-Skogen joined the center’s team in early 2023, then a little over a year had elapsed since the allegations against him became public. It would be next to impossible for him to complete even the shortest route to formal behavioral health training by the date of this writing, much less the date he joined Seeking Integrity. An accredited MSW program typically takes two years to complete, though some fast-track programs cut it down to about 16 months. California requires LCSW applicants to first gain “3,000 total supervised hours, over 104 weeks (minimum)” of experience and pass a clinical exam.

When Henzie-Skogen’s bio first appeared on the Seeking Integrity website, it described him as “A lifelong professional musician, educator, and clinician.” It didn’t specify the meaning of the term “clinician,” which can describe people in the music world (i.e., a person teaching a music clinic) and in the behavioral health world. Tone Madison reached out to Seeking Integrity in March with questions about the term, Henzie-Skogen’s role at the center, how much the center’s staff and clients knew about Henzie-Skogen’s background, and how the center is regulated and accredited. Stuart L. Leviton, Seeking Integrity’s Chief Operating Officer, replied but declined to comment: “As a company, we do not respond substantively to inquiries regarding personnel.” But shortly after, the page was edited to remove the term “clinician.”

Thyer points out that behavioral health licensing laws are broad. Even someone with a state license or professional certification has a lot of legal latitude to practice as they see fit—say, using tarot cards or numerology, Thyer says—as long as they don’t have sex with clients or commit financial improprieties. The social work profession “does not handle this very well,” Thyer says.

Sizing up a practitioner’s qualifications is even more murky when it comes to treatment for sex addiction. To begin with, the mental-health field has never reached a consensus on whether or not sex addiction is real. A disordered relationship to sex can factor into many recognized mental disorders. The debate is over whether concepts like sex addiction and porn addiction constitute mental illnesses in and of themselves. Sex addiction is not in the DSM-5, nor does the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which publishes the DSM, recognize it. The World Health Organization began recognizing sex addiction in 2018, formally terming it Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD). To make things more complicated, the APA published a 2021 book that details scholarship and treatment practices around these concepts.

One of the leading organizations that sets standards for sexual health practitioners rejects the concept of sex addiction. In a position statement first issued in 2016, American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists (AASECT), stated:

AASECT recognizes that people may experience significant physical, psychological, spiritual and sexual health consequences related to their sexual urges, thoughts or behaviors. AASECT recommends that its members utilize models that do not unduly pathologize consensual sexual behaviors. AASECT 1) does not find sufficient empirical evidence to support the classification of sex addiction or porn addiction as a mental health disorder, and 2) does not find the sexual addiction training and treatment methods and educational pedagogies to be adequately informed by accurate human sexuality knowledge. Therefore, it is the position of AASECT that linking problems related to sexual urges, thoughts or behaviors to a porn/sexual addiction process cannot be advanced by AASECT as a standard of practice for sexuality education delivery, counseling or therapy.

By extension, there’s also not much consensus on how to treat sex addiction and other disorders that relate to sex in some way. “Some things are pretty good, like erectile dysfunction… but if it comes to things like pedophilia, somebody who’s aroused by violence or non-consensual sex, getting people to not be aroused by those features of sex and instead be aroused by non-consensual adult sex, there’s very little in the way of what could be called research-supported treatment for that,” Thyer says.

Seeking Integrity’s website provides bios for 16 staff members. Ten of them, including Founding Director Robert Weiss, have some form of professional licensure as therapists, LCSWs, psychologists, and/or medical doctors. Another lists certifications from the International Institute for Trauma and Addiction Professionals (IITAP). (IITAP is something of a rival to AASECT, and has criticized AASECT’s 2016 position statement on sex addiction.) The other five mostly serve in executive or administrative roles. Among those not listing a formal clinical certification is Seeking Integrity’s Director of Online Education, Scott Brassart, who is registered as a sex offender in Illinois. The Chicago Tribune reported in 2010 that Brassart “pleaded guilty to child abduction for trying to lure an 11-year-old Southwest Side boy into his car in 2000, records show.” Brassart’s Seeking Integrity staff bio, much like Henzie-Skogen’s, similarly offers no specifics about his history, stating that “for the last 15 years he has worked almost entirely on healing sex addiction, porn addiction, and paired substance/sex addiction.” (Brassart did not respond to a request for comment for this story.)

Seeking Integrity’s website offers paid “Online Support Sessions” with four different staff members, including Henzie-Skogen and Brassart. “These sessions provide a compassionate, judgment-free environment to explore your unique situation and identify the best path forward whether through helping you find the right therapist, committing to a workgroup, or additional resources,” the website states, going on to note: “Our Virtual Support Sessions are not therapy, nor are they a substitute for therapy.” A session with Henzie-Skogen, focused on “Support for Sex, Love, and Porn Addicts,” costs $60 for 25 minutes or $100 for 50 minutes. A separate bio in this section of the Seeking Integrity website describes Henzie-Skogen as “Generous. Enthusiastic. Tranquil.” This bio also states that he has “supported countless individuals in their struggles” and “spent over 40 years as a professional musician and educator.” Henzie-Skogen is in his mid-40s, so this implies that he has been a professional musician and educator since he was a small child.

A quiet return to the music scene

Youngblood Brass Band announced its fall 2025 European tour this summer. Conspicuously absent in the band’s social-media posts and website were any mention of whether or not Henzie-Skogen would be taking part in the tour. Publicity materials for the tour include photos that show Henzie-Skogen. The band’s website lists him as a current member. At some point, the band’s Wikipedia page was edited to note that Henzie-Skogen has returned to the band.

Without Henzie-Skogen, Youngblood would truly be embarking upon a new chapter. Henzie-Skogen isn’t just the band’s drummer and occasionally rapping frontman. He’s been at the creative heart of Youngblood since its beginning, taking part in everything from composition and arrangements to mixing records to handling the band’s business affairs. Even if Henzie-Skogen weren’t along for the tour, he’d be the elephant in the room.

The last tour date listed is an “educational workshop” in Lille, France, on November 20 at the Conservatoire de Marquette-lez-Lille. It’s not clear whether or not this workshop will be open to minors, or whether Henzie-Skogen will have a role in it. The conservatory hosting the workshop offers musical education for children and adults, according to its website. An event listing on the conservatory website states that the event is free and open to “tout public,” or all audiences, basically. The conservatory did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

After the allegations against Henzie-Skogen became public in fall 2021, Youngblood trombone player Joseph Goltz responded to a Tone Madison inquiry by announcing the band would part ways with Henzie-Skogen.

“In light of the upsetting allegations raised against David Henzie-Skogen, all current Youngblood Brass Band members are in agreement that we will no longer be working under his leadership or with his label, Layered Music, going forward,” Goltz wrote in an email at the time. “We don’t know what this means for our future as a band and as individual musicians, and we are absolutely gutted. But our pain is nothing compared to that of the victims coming forward. We thank them for their courage and will hold Dave accountable.”

Goltz did not respond to a request for comment for this follow-up story.

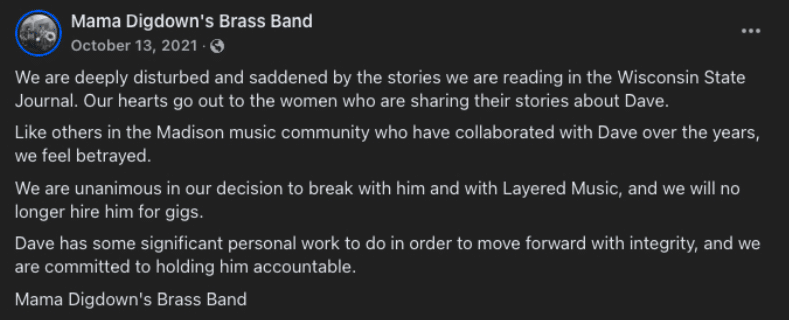

Mama Digdown’s Brass Band also publicly parted ways with Henzie-Skogen in October 2021. A week after the Wisconsin State Journal published the first news story about the allegations, the band issued a strongly worded statement through its social media accounts:

“We are deeply disturbed and saddened by the stories we are reading in the Wisconsin State Journal. Our hearts go out to the women who are sharing their stories about Dave. Like others in the Madison music community who have collaborated with Dave over the years, we feel betrayed. We are unanimous in our decision to break with him and with Layered Music, and we will no longer hire him for gigs. Dave has some significant personal work to do in order to move forward with integrity, and we are committed to holding him accountable.”

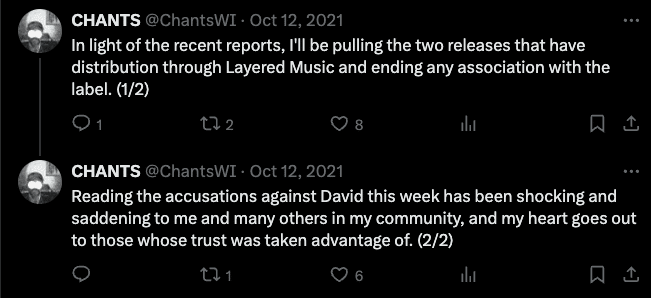

At that time, Mama Digdown’s member Jordan Cohen also issued a direct statement breaking with Henzie-Skogen. In addition to drumming in Mama Digdown’s, Cohen has a solo electronic project called Chants that had issued two past releases on Henzie-Skogen’s Layered Music label. (Full disclosure: Cohen is the host and creator of Digital Warmth, a podcast that was hosted here on Tone Madison from 2019 to 2020.) Reached for comment for this follow-up story, Cohen stuck by the position he took in 2021.

“I can only speak for myself, but I have not worked with David Henzie-Skogen and will not do so in the future, in any band or capacity,” Cohen says. “I think everyone should listen to and believe the victims.”

Chris Di Bernardo, a former Shadow student, played in Mama Digdown’s Brass Band for nearly 10 years, leaving in February 2024. (He has since relocated to Nashville, where he continues to work as a session drummer, play in the Madison-founded band Mickey Sunshine, and develop his solo jazz material.) Di Bernardo has found Henzie-Skogen’s re-emergence upsetting, because he considered Henzie-Skogen a mentor from the earliest stages of his music career, and doesn’t think Henzie-Skogen has done enough to take responsibility for his actions. Di Bernardo joined Shadow in 2009, as a sophomore in high school. After graduating, Di Bernado kept in touch with Henzie-Skogen. “He wrote me a letter of recommendation for colleges,” Di Bernardo recalls. “I started out subbing for him as a member of Mama Digdown’s Brass Band, which eventually grew into more of a full-time role with the band over the last almost 10 years.”

When he learned about the allegations in 2021, Di Bernardo shared in the Shadow community’s sense of shock and betrayed trust. “I actually found out directly through one of my friends who I marched with, who was directly impacted by Dave and his grooming behavior,” he says. Di Bernardo says he hasn’t heard from Henzie-Skogen since 2021.

Di Bernardo is clear that he didn’t experience that behavior himself and doesn’t presume to speak for the women who say Henzie-Skogen behaved inappropriately with them during their time as his students. He recalls having a positive experience in Shadow, which just throws the pain of his female classmates into sharper relief.

“Obviously, because I’m a male, I benefited from, like, positive grooming… that’s what he’s supposed to provide, not the grooming, but the positive mentorship and leadership,” Di Bernardo says.

Over the past four years, the women who say they experienced grooming or sexual misconduct from Henzie-Skogen have worried about the possibility of him re-integrating himself back into Madison’s music community. They’ve wrestled with the need to move on and their desire to do what they can to prevent further harm. They refuse to let their experiences with Henzie-Skogen define their lives, but they also refuse to let it happen to anyone else again.

Steph, for one, also refuses to let this ruin the good things she took away from her time in Shadow. Friendships with former classmates last, and so do (for some Shadow alums) the matching tattoos. And despite everything, the benefits of learning from undeniably talented teachers and musicians can last, too.

“Dave doesn’t get to own that experience for everyone, and he doesn’t own it for me,” Steph says.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.