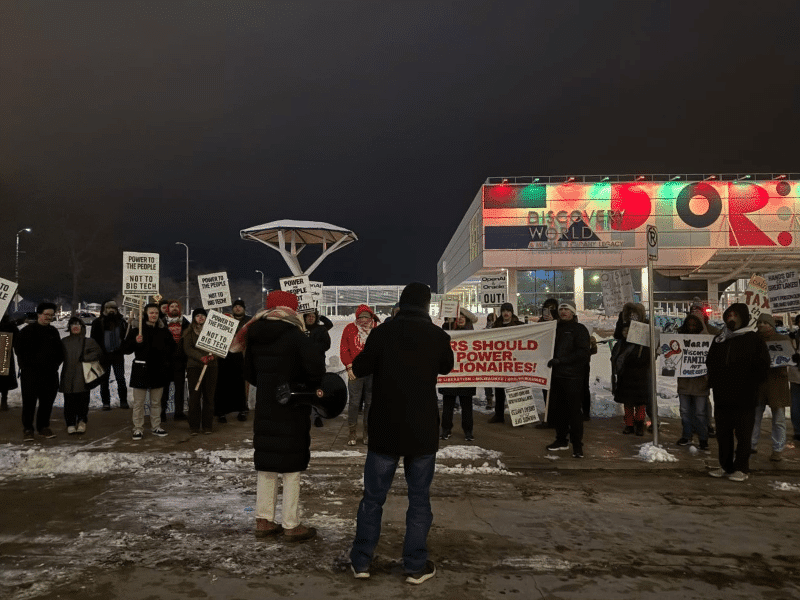

A leftist critique of top-heavy public institutions

More investment in the actual laborers will better serve everyone.

More investment in the actual laborers will better serve everyone.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

In a 2015 interview, Ira Glass, founder of the popular radio show and podcast This American Life, talked about why he asked his employers, WBEZ Chicago, to lower his income.

“[A]nd I just felt like, ‘I don’t know, it seems weird to be making this much money and asking people to donate money,’ It seemed unseemly,” Glass told Kansas City public radio station KCUR. “So I said, ‘I think that I should just make less.’ I just thought it … seemed fair. It seemed like I should make what you make if you’re like, a high school principal or something. Not even the principal, but the assistant principal.”

By contrast, UW-Madison Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin earns $900,000 per year. With merit raises and retention bonuses, Mnookin could earn over $1 million in 2025.

It’s easy to pick on Mnookin’s outlandish salary, but an uncomfortable truth with our public institutions is that many are top-heavy. The bulk of their funds go to the bloated salaries of administrators. And while some administration is necessary to run an organization, those institutions and the administrators themselves have to know somewhere deep down that most of those positions are bullshit jobs. And anyone who thinks administration is harder or more stressful than teaching a classroom all day or driving a bus is kidding themselves.

After he was appointed, one of former Metro Transit General Manager Justin Stuehrenberg’s first initiatives was to create four new “chief” positions, three of which were placed in the City’s highest salary designation. Instead of promoting from within, Stuehrenberg hired new people and, in addition to their high salaries, they received paid moving expenses in excess of what the City allows. All three of those chiefs are no longer with Metro Transit and, unsurprisingly, did not solve the department’s problems. Because the problems at Metro Transit do not stem from a lack of administration, but from a lack of drivers and mechanics—the people who actually do the essential work.

For people who are not fascists or at least support the existence of public institutions, it feels risky to say this critique out loud as right-wing extremists continue their ongoing onslaught on any and all public goods. The distinction is that the right doesn’t want public goods to exist or to be available to the public, and there’s nothing those institutions could say or do that would change their position. What I’m critiquing is not the existence of those institutions—I want good schools, public health, public transit, etc.—but those institutions failing to meet the values inherent to their mission and to public service in general. It’s much harder for an institution to provide quality public services when the bulk of their money is going to bloat at the top instead of the people doing the actual work.

The right also does not want public jobs to be good jobs; former Gov. Scott Walker demonstrated that by undermining the power of public unions (except, of course, for cops). Walker hoped governments would seize the opportunity to race to the bottom and pay their employees as little as possible. Of course, those changes affected the salaries of people at the bottom rungs of the ladder, but not those at the top who make budget and salary decisions. As a result, our public institutions’ income distributions are mirroring the income gap we see in our society at large.

We should be able to hold our institutions to a higher standard, because we are paying for them. I do not want the bulk of our tax dollars to go to administrators who earn five to 10 times more than the actual workers—teachers, maintenance, custodians, drivers—who make the institution function. I want institutions and institution leaders who value their workers enough to not just say it but to show it with an income distribution that matches the needs and values of the organization. And I want the public, including students, to be able to affordably access those services.

The neoliberal argument for those high wages has been that these public institutions have to “compete with the private market.” But there has always been a tradeoff with public vs. private jobs. Public jobs pay less but provide better benefits, more stability (although that is TBD, thanks to the Trump administration) and the opportunity to work to provide a public good. Private positions pay more, but you often have to deal with potential layoffs and more meager benefits.

“But then Mnookin and others would go elsewhere to earn more.” OK, let her. For a fraction of what she earns, I’m sure we can find someone else who would value UW-Madison’s educators and researchers, and who would not call the cops on peaceful student protesters, nor waste university funds on consultants and tech. A million dollars is enough to buy a house in Madison with cash and still live a perfectly comfortable life. Meanwhile, the teachers, staff, students, and taxpayers are struggling to make ends meet. Anyone who actually values the institution, the people who make it run, and the value it brings to the public would see how unseemly that is, and change it.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.