Unlearning the impulses of austerity

If we’re going to not only survive but thrive, we will have to do it together.

This is our newsletter-first column, Microtones. It runs on the site on Fridays, but you can get it in your inbox on Thursdays by signing up for our email newsletter.

Austerity is violence. Those who have lost their jobs due to DOGE’s asinine actions know this. So do the researchers and academics who see not only a financial cliff at the end of their current grants, but a black hole threatening to suck up all their work. All that investment of people’s time and energy into training and learning—even before the research itself—wasted. That’s not even factoring the lost benefits of that research on society at large.

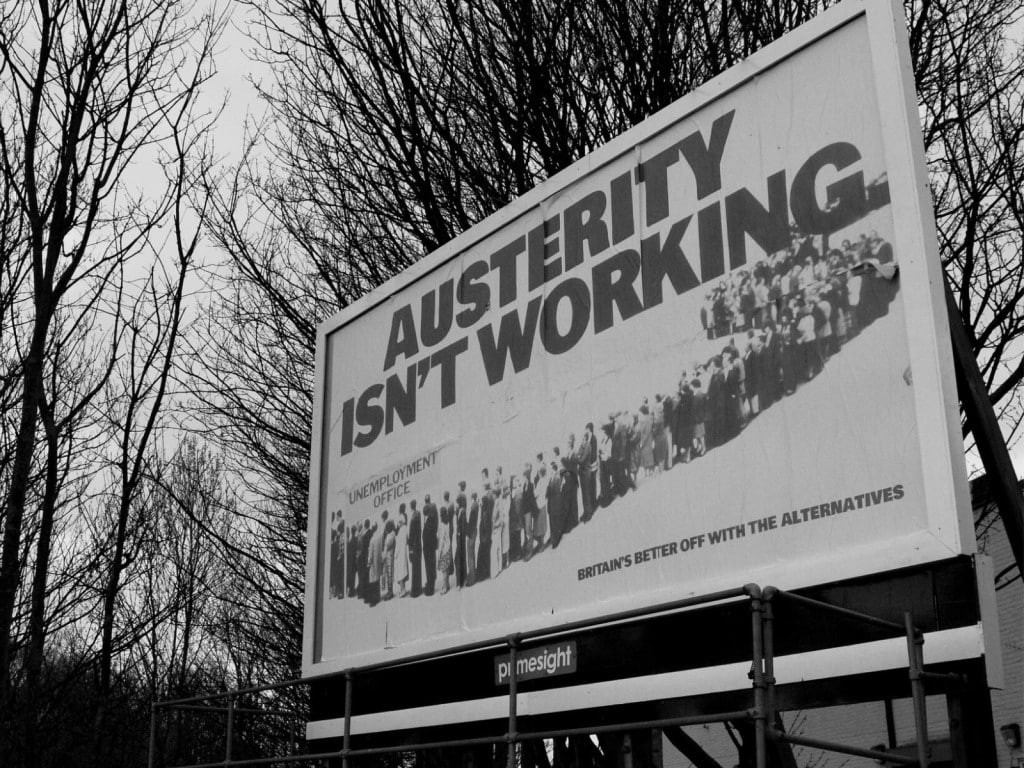

That violence goes beyond jobs and lost potential, as traumatic and shortsighted as that is. Dane County employees, particularly those in the Department of Public Health and Human Services, know the violence of budget cuts, but so do the people who rely on those services. And the ramifications will be larger than we could realize. The UK government implemented austerity measures in 2010 at the height of the financial crisis, which increased mortality rates by 3% according to researchers at the London School of Economics and Politics.

“Several factors contribute to the rising death rates. One significant cause we identified is the increase in ‘deaths of despair,’ which include drug-related deaths,” the researchers write. “We estimate that austerity measures led to around 1,000 additional deaths from drug poisoning between 2011 and 2019, accounting for about 3% of all drug-poisoning deaths in the United Kingdom during that period.”

As if death (particularly deaths of despair), job losses, lost potential, and stalled research weren’t enough of a toll, there’s another casualty of austerity we need to be wary of: community. We’re already seeing this play out in Madison in the fallout of the decision to close Dairy Drive. Several people I respect have drawn opposing lines, and they are lobbing volleys at each other across social media and press releases, instead of working together to find solutions to get unhoused people into homes.

It’s understandable, given the stakes. I don’t know what it is about the Mayor’s office or City staff and how they’re able to convince so many people that there is only one option; but if we’re going to make it through crises (and there will be multiple crises in the upcoming years), we have to remember that there are always multiple options available.

All of this could have been avoided if everyone hadn’t given in to an austerity mindset and instead found resourceful ways to fund Dairy Drive. The City could have approved Madison Street Medicine’s application for federal Community Development Block Grants, extended Madison Street Medicine’s contract (at no cost), and Madison Street Medicine could have sourced funds from Dane County, the state, Housing and Urban Development, or local donors. We wouldn’t be tearing each other down, and unhoused people wouldn’t be thrown out onto the street before winter.

The reality is that no one is coming to save us. In fact, it’s that mentality that led to Trump being reelected anyway—the patriarchal idea that a strong man can take over, punish all the “undesirables,” and fix everything. Part of its appeal is that it allows ordinary people to abdicate responsibility and hand over the keys to someone who promises that only they can save us. We got ourselves into this mess. Now we, as a community, will have to get ourselves out of it. First, we have to relearn how to be a community.

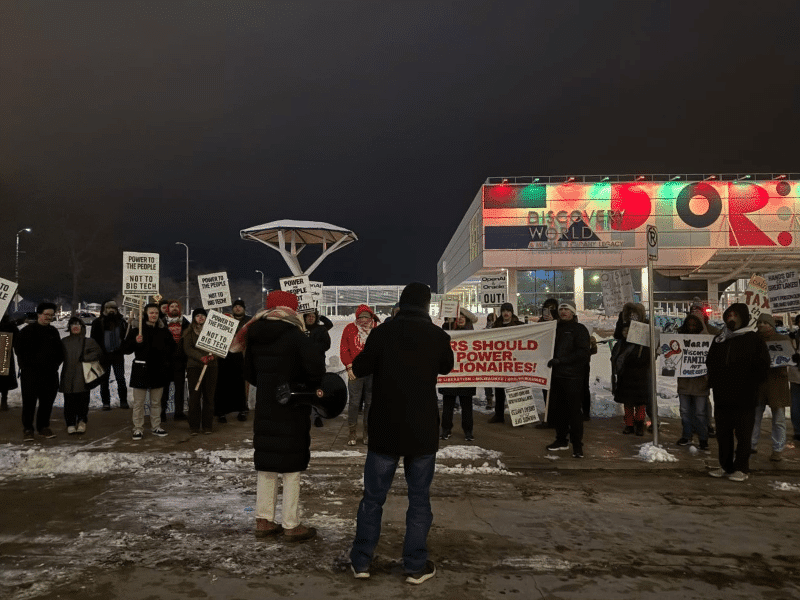

A few weeks ago, MadWorC, in partnership with other Madison cooperatives, including Tone Madison, organized a regional rendezvous. Activists and worker-owners in cooperatives across the Midwest came to Madison and spent two days discussing the new world we would like to see and how cooperative ownership can be part of that future. One workshop I attended examined the values of capitalism—individualism, hierarchy, profit—compared to the values of a cooperative society—solidarity, equity, and a system that prioritizes meeting people’s needs. It highlighted the gulf between where we are and where so many of us want to be. We want to build community, but the values and skills we’ve learned to succeed under capitalism are antithetical to community.

Austerity exacerbates that gulf. The impulse under austerity is to hoard resources and circle the wagon. It’s a myopic response that prioritizes only a narrowing number of people’s needs. Maybe that’s why fascism seems to follow the wake of economic collapse—as resources feel scarce, some people respond by setting hard lines for who belongs and who’s deserving. But that impulse—to hold tight, make drastic cuts, and look out for your own—only exacerbates the problem. Healthy economies depend on money flowing. If it stops—say, it disappears in the bottomless pockets of the wealthiest—then, like a series of dominoes, everyone starts to buy less and earn less. Everything shrinks and everyone is impacted, but none more so than the poor, who see their pittance of resources dry up. Austerity exacerbates class warfare and inequality.

The lie behind austerity is that it’s just dollars and cents. And too many of our politicians look at the numbers, shrug their shoulders, and feign helplessness. But austerity is bad for economies, as we are living in the reality that decades of austerity has wrought. We have to interrogate and unlearn the impulses of capitalism and austerity to reverse the downward spiral. We have to learn how to navigate the messiness of conflict, and allocate resources to the least among us, in order to truly live as a community. If we are successful, we could not only survive, but rebuild a world where we all can thrive.

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.