The shifting identities of “I-Be Area” offer a radical commentary on isolationism of the digital era

Ryan Trecartin’s queer, postmodern 2007 video-art feature screens as part of MMoCA’s Rooftop Cinema series on August 14 at dusk.

The promise of digital tools democratizing art has always been a false one, but during brief periods in the last 30 years we have seen genuinely radical work break through to wider audiences. Perhaps the most important such period in the history of digital video arrived with the advent of YouTube in 2006, when it first became the one-stop shop for freely available digital content (before Google acquired it), and Vevo and other services made it just another arm of the overculture.

During this period, we saw the rise of the viral video to document the cultural moment with aesthetics that were often unstudied or accidental. The ease of creation with decent consumer-grade digital cameras turned anyone into an artist of sorts. But, of course, capital-A Artists were exploring the trend themselves, including Ryan Trecartin, who perhaps emerged as the figurehead of the gray area between experimental art and viral entertainment.

As Trecartin says, “We always invent things inside the limits of our imagination. We’ll call it a ‘page’ instead of making a new word for it, because we’ve invented it based on things we know. So I feel like the internet already is us and was always us.” The internet was just the medium of the day, like acrylics in the 1930s, but even more accessible to artists, both as raw material and a public commons in one. It created new avenues for immediate creation and release, which helped Trecartin initiate a torrent of pure creativity that channeled the highs and lows of culture into one concentrated stream of mania.

As he and his crew bent and broke the possibilities of Final Cut Pro, Trecartin’s first feature-length project I-Be Area (2007) became a calling card and a quintessential piece of internet-age video art. The seminal absurdist film is screening as part of Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (MMoCA)’s Rooftop Cinema series on Thursday, August 14, at 8:30 p.m. (or shortly after dusk). In the event of rain, the screening will be moved inside to the first-floor lecture hall.

Beginning with a pair of children starring in infomercials for their own adoption, I-Be Area then jets into an unraveling narrative with the clone I-Be II (Trecartin), who refuses to meet his “primary.” I-Be II then decides to rapidly transition to “Oliver,” a femme identity sold to him by a woman he meets through video chat.

These are only two of eight characters who Trecartin plays over the course of the film, along with friends and fellow artists (most notably, his longtime creative partner Lizzie Fitch), who take just as much pleasure in the absurd possibilities of drag. The alternate reality’s confusing standards for both adoption and cloning recur throughout the film, which doesn’t have a traditional plot so much as a loosely connected series of scenes that regularly take hard-left turns in tone and concept.

Its seams are visible; nearly every set is a domestic space with visible beds and couches, sometimes presented as-is and sometimes painted or strewn with items that ask viewers to imagine something different. The spaces are largely transformed through the power of editing and chintzy digital effects that call to mind the desktop surrealism of Michael Snow’s *Corpus Callosum (2002). Trecartin’s work crafts a distinct feel through a rapid-edit technique: actors learn and shoot their lines one by one, often delivering them directly to the camera, making all conversational rhythm and spatial relation feel stuttered and alien.

The language spoken in I-Be Area is nonsensical, as 80% resembles human speech but zigs when the viewer expects a zag. “The world ended three weeks ago, starting now,” says one of Trecartin’s alter-egos, after referencing a “big piece of daydream gas.” Nothing in the film really resembles human behavior, and when it does, it’s as a cutaway gag to puncture the heights of everything else. Characters occasionally repeat lines with different intonation in the same shot, suggesting a flubbed or alternate take that was left in. But this is all part of Trecartin’s maniacal plan, part and parcel with his interest in the malleability of language and the ability to turn one thing into many. Mirroring the clone plot, Trecartin reuses language, space, and actors all to unfold the possibilities of each form.

When not referring to dizzying plot details that can only be half-understood, the film’s characters speak to a sense of isolation and uncertain identity in the digital age. “I just hate when I don’t know that I’m multitasking,” says one character. I-Be II says that a conspiratorial “they” have “decades they’re keeping from” him, after “I ain’t never seen my neighbors, ain’t no small world here.”

The film’s focus on generative new versions of the self, particularly when most are in disheveled drag, seems to lend itself to an explicitly queer and trans reading of the work. But these splintered selves also speak to the compression of history and memory that happens as a result of information glut. Approaching I-Be Area nearly two decades later, social media has driven us further towards constant documenting and a psychological existence closer to distinct other selves and realities. Many characters—painting themselves with face makeup that splits the difference between immaculate, glam contours, and blotchy clown makeup—affect their behavior even beyond the typical exaggerations of drag performance. Each gesture is so heavily in air quotes as to be unrecognizable.

But the exaggerations still possess truth, like primal screams into and out of the machine. What does camp style look like in an accelerated, hyper-ironic age? Probably something like this film, where the Baudrillardian layers of remove leave nothing but irony to build off of. Camp becomes reality, and the embodiment of queer hyper-gesture becomes not just an in-sign but a new semiotic system upon which to build experience.

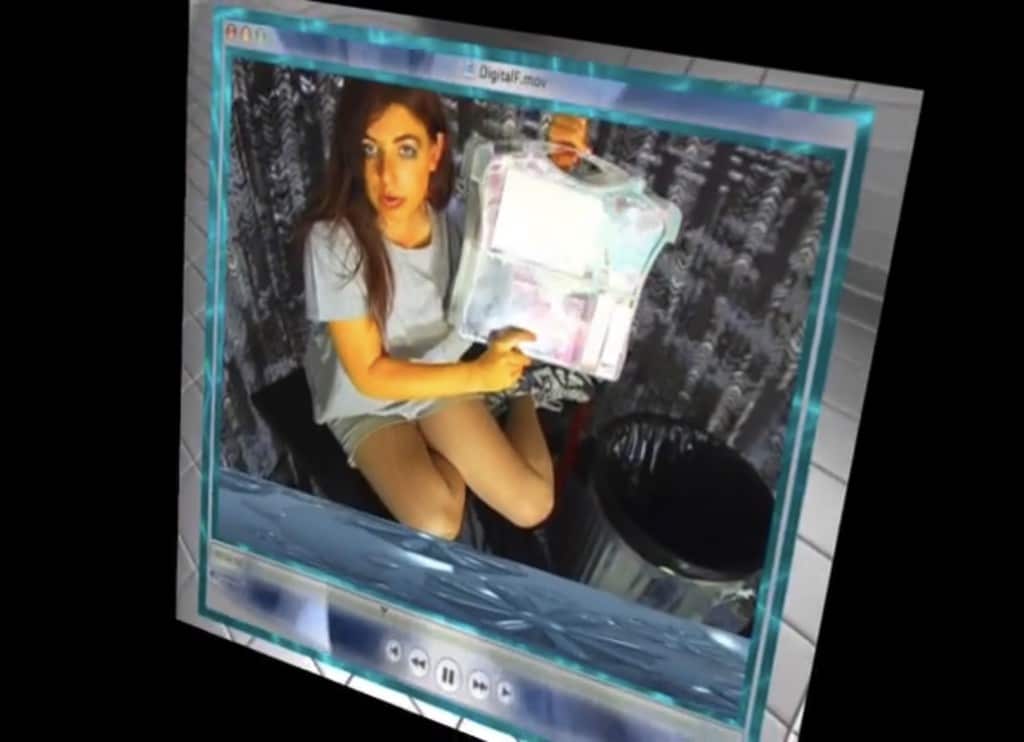

Trecartin’s work, while shown in galleries, has long been freely available on the internet as well. This casual accessibility, as is the case with so much internet-native video art, means that the work is usually encountered within the degraded spaces of browser windows (consciously anticipated by the occasional media player in I-Be Area serving as a frame-in-frame). It shares enough scrappy qualities with the viral videos of its day that the distance between I-Be Area and Liam Kyle Sullivan (or Kelly)’s “Shoes” (2006), for instance, is more a matter of context and perspective.

For all its creative and conceptual rigor, I-Be Area is also a document of art. Trecartin has famously lived with his collaborators in many of the environments they’ve shot in. I-Be Area has become one of his most accidentally poignant works, documenting the house Trecartin and co. built after their previous home (featured in his breakthrough A Family Finds Entertainment) was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

Per a recent interview with Dennis Cooper, Trecartin is now involved in his largest-scale project, making a sort of live-in theme park-cum-art installation in Ohio. He’s focused now, more than ever, on creating durable yet malleable forms that can change meaning in context. In this case, he means buildings and sets, but this has arguably always been the case with his videos. As time marches on and the signifiers of 2007 have become dated, a work like I-Be Area is still ripe for new and developing interpretations—particularly as a loose narrative about transness and the fight for the soul in an increasingly technocratic society. As buildings fall and the internet is consolidated to a small handful of corporate entities, videos like this will be what remain—artifacts of impossible places.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.