“Dogfight” is an unsentimental masterpiece about two souls searching

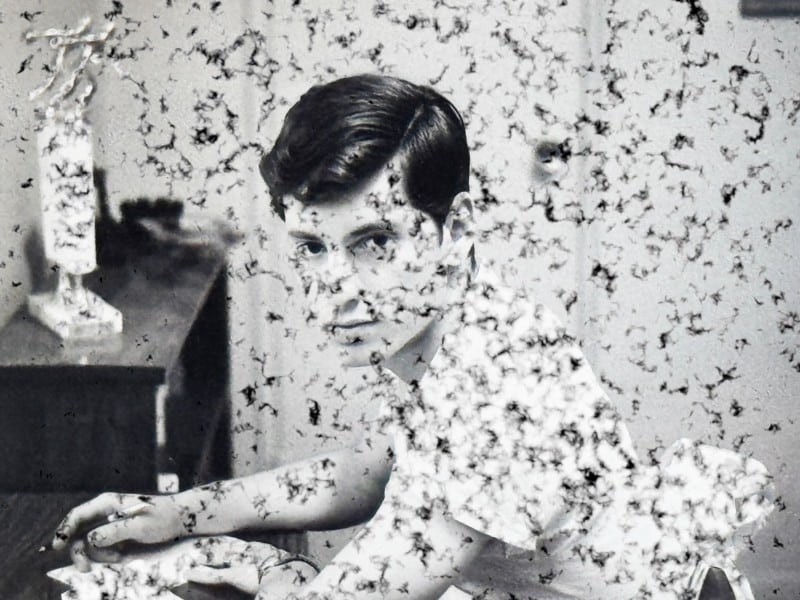

Nancy Savoca’s coming-of-age romance screens at UW Cinematheque on September 20.

Nancy Savoca’s coming-of-age romance screens at UW Cinematheque on September 20.

When done right, a one-night movie—that is, set over the course of one night, and approximating real time—creates an urgency that is hard to refute. Characters may cherish a last hurrah together, or find themselves in a first chance encounter that sways their attitudes and changes their lives forever. In the case of the latter, Nancy Savoca’s Dogfight (1991) is just about peerless, and a deeply-felt romance that outpaces even the colloquial warmth of Richard Linklater’s Gen-X touchstone, Before Sunrise (1995).

Newly released on Blu-ray at the end of April by Criterion Collection—and further bolstered by actress Kerry Condon calling it her “favorite movie” the same day—Dogfight is, to borrow a phrase from the barely-of-military-age boys in the film: out-fucking-standing. As part of a trio of Nancy Savoca films on Fridays this month before her in-person campus visit on September 27, UW Cinematheque is offering Madison audiences a chance for the communal experience with a free DCP screening on Friday, September 20, at 7 p.m., in 4070 Vilas Hall.

Setting the story in San Francisco during the day prior to the Kennedy assassination on November 21, 1963, Savoca and writer Bob Comfort weave an unsentimental period piece. Dogfight reveals pretenses of gender, poignantly examines surrendered innocence, and tenderly hones in on the ineffaceable connection between two people who’ve yet to turn 20. Namely, the foulmouthed, impulsive Lance Corporal Eddie Birdlace (River Phoenix) and the mild-mannered aspiring musician Rose Fenny (Lili Taylor).

The two meet when Birdlace and his band of brothers, nicknamed The Four Bees, play the mean-spirited party game that gives the film its title. The young Marines each throw $50 into the pot, and the one who brings the agreed-upon “ugliest” date to the bar (after much drinking) takes home a pile of cash. While perspicacious for her age, invested in the social power of American folk and protest songs, Rose is at first oblivious to this brand of personal cruelty. Birdlace dupes her into believing she’s attending a dress-up party. And so, when she learns the boys’ intentions, she chides them for carrying out a childish initiation ritual equally fueled by toxic masculinity and their feelings of impending doom (as the Marines will tomorrow ship out to Okinawa, and then to Vietnam).

Stricken by guilt, Birdlace chases after a tearful Rose, and the two end up hoofing it around the fluorescent-lit San Francisco streets, parks, restaurants, clubs, and Victorian houses (all presented with remarkable production detail). A mere hour after Birdlace humiliates Rose with a sophomoric game, the couple vigorously confront one another’s prejudices in earnest conversation. Phoenix and Taylor fully inhabit the vulnerabilities of these two individuals in the process of figuring out the world, pondering the physical and metaphysical dimensions of falling in line or striving to affect the status quo.

The act of conscious listening is so integral to their realizations and divergent worldviews harmonizing. Dogfight is remarkable because it takes the concept of two young people perceiving one another for the first time (see also: Before Sunrise), and elevates it not only through the use of its period-accurate music (Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, The Weavers, etc.), but through Rose’s personality poetically reflecting that musical ethos.

The songs aren’t just window dressing; they’re vital to Rose’s values. This is especially audible—and visible—during a scene in the Still Life café in North Beach. Rose timidly sits at the piano and simply plays Malvina Reynolds’ “What Have They Done To The Rain” to an audience of just Birdlace. As he takes in Rose’s soul-baring performance, DP Bobby Bukowski’s camera slowly zooms in towards his sloped gaze. In cross-cutting shots, Birdlace seems to contemplate his entire life, Rose’s, and their lives together all in the span of 90 seconds.

However, this stirring vision for the characters and the film may not have come to fruition, as Taylor and Savoca told filmmaker Mary Harron in a recent interview (included on the Criterion Blu-ray). After receiving audience reactions from the initial test screenings, the Warner Bros. studio wanted to shape the film into a more popular, palatable John Hughes-like comedy. Savoca and the late River Phoenix defiantly rejected the meddling. This whole marketing ordeal actually echoes the attempts to alter and dilute Martha Coolidge’s Valley Girl (1983) in the prior decade of American independent film.

Dogfight stands not as an anesthetized, remember-the-days yarn about the follies and shenanigans of youth. Rather, it looks matter-of-factly at the human capacity for cruelty, compassion, and most significantly, change. This is most true for the plainly immature Birdlace, but the rigid Rose finds a lot to re-evaluate, too. She learns to recognize the passionate contradictions in someone who may not align with her interests or concerns, but is similarly seeking validation and acceptance. Kerry Condon was right to emphasize how this film honestly conveys the effect of love on the soul. It’s more of a compliment to realize that Dogfight manages to convincingly do that, even excluding its heartbreaking epilogue, in one fateful night.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.