Quan Barry refuses to look away

In her new poetry collection, “Auction,” Barry sees beauty in life’s ugliness.

In her new poetry collection, “Auction,” Barry sees beauty in life’s ugliness.

In Auction, Madison-based poet Quan Barry explores the spaces where beauty and ugliness co-exist—all over the world and right here in Madison. This collection, published by the University of Pittsburgh Press in 2023, is the author’s first poetry book in eight years. It’s gritty, thought-provoking, and sometimes shocking.

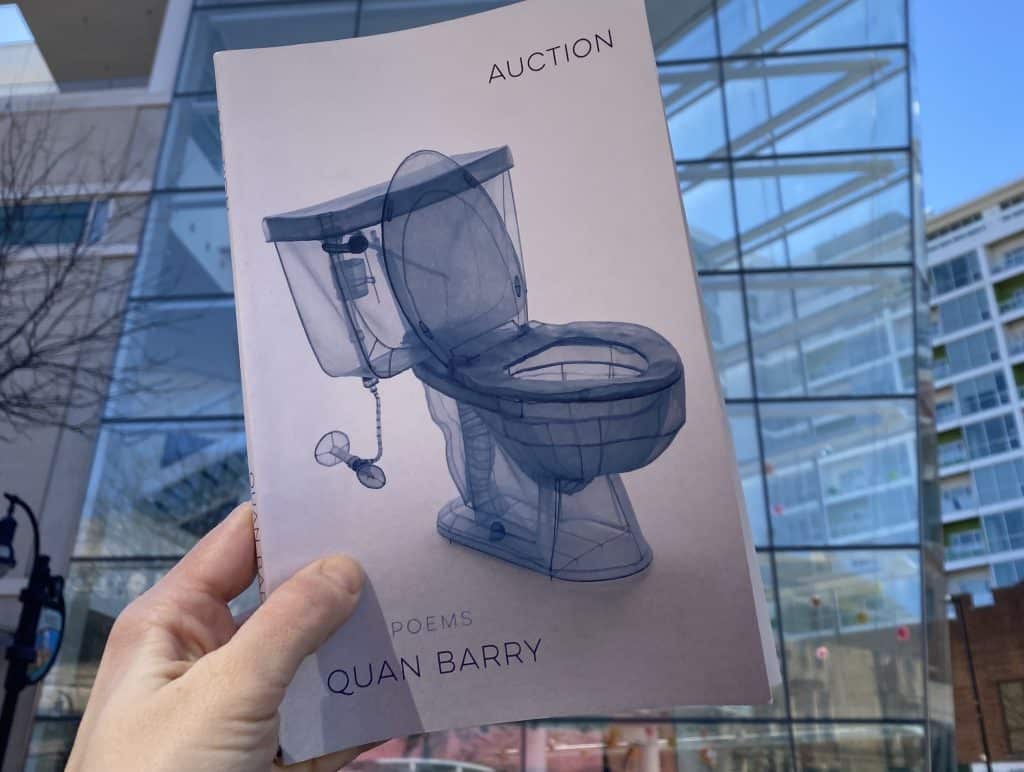

The book’s connections to Wisconsin begin on the cover, which shows a translucent toilet created by Korean artist Do Ho Suh. This sculpture appeared in a 2017 exhibition of Suh’s work at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, which inspired Barry’s poem “Apartment A, Unit 2.” In the exhibit, Suh recreates an entire apartment out of fabric, which gives everyday objects a ghostly look.

Barry says that the toilet image works on the cover because it communicates “looking into things—looking beyond their surfaces.” In “Apartment A, Unit 2,” she explores what it means to look deeply into a soul—even a soul of an appliance—and refuse to look away.

…what it looks like

when the refrigerator leaves its own body, the afterimage

as even an appliance is allowed to remember

that once it was infinite

and still is, home like a medusa, that ghostly lantern

pulsing in the dark, the things we see

in the first moments after we pull the cord

and throw the world into night…

In these lines, the speaker adjusts her eyes to look past the opaque edges of an object and into its inner workings. Barry takes this same approach throughout the book—even when those inner workings are horrifying to look at.

In “Rough Air,” Barry shares snippets, many of them ugly, from trips around the world—a rat in a hotel storage closet, an elegant birthday cake made of elephant dung, a gun raised above the speaker’s head along a beach road, ocean waves so strong they break swimmers’ necks. Barry says this poem was originally many different poems. “I realized that I had a lot of poems that were about travel, and I could put them together and give them a structure of having a speaker talk about the ethics of travel,” she says.

Travel has notably inspired her writing—she’s published novels inspired by trips to Vietnam (She Weeps Each Time You’re Born) and Mongolia (When I’m Gone, Look for Me in the East), and her forthcoming novel takes place in Antarctica. But lately, her relationship with travel has changed, a shift that becomes clear in “Rough Air.” The poem grapples with the trouble of “staying in motion” as a way to avoid looking through your own opaque edges to see the complicated ugliness underneath.

Sometime around forty I said: soon

I’m going to give all this up—

the need to be elsewhere

as if elsewhere is better.

…

I didn’t ever have to look within as I was preoccupied

with looking out.

Ultimately, traveling elsewhere isn’t a solution for avoiding a good, hard look in the mirror.

“I’m slowing down in certain ways,” Barry says about her relationship with travel. “And I don’t say this to try and curb anyone else’s fun or sense of possibility, but now we’re much more aware of the ethics of travel and what it means to go to certain places, thinking about carbon footprints, thinking of places that haven’t had as many western travelers—what that means to introduce western culture into some places.” From “Rough Air:”

…

Now they say don’t use guidebooks, bring your own

fork and knife, stay longer in one place, hire local people,

eat what they eat, do what they do, blend in, roll

your clothes, pack out what you brought in,

don’t go in the first place

…

Barry was on a trip to Australia when the pandemic lockdown began in March 2020 but hasn’t gone on any big international trips since then. Now, she sticks closer to home. And fittingly, the poem finds its way back to Madison by the end, referencing the protests in downtown Madison in May and June 2020 against the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis:

…

E.g standing on a street corner in Dakar, smelling the same tear gas

I smelled in Madison, the Wisconsin air scorched unbreathable

in the name of property.

…

Violence is one of many themes that weaves its way through Auction, but Barry says she didn’t set out to write a highly thematic collection. “There are themes in it, but none of them are intentional,” she says about Auction.

“A lot of what I do, as a writer and as an artist, is intuition,” Barry goes on to say. “I can’t necessarily articulate why I do certain things. I can’t cook, but I imagine it’s what cooks do. You taste it and say, ‘Yeah, that’s about right.’ I’m trying different kinds of things and just feeling what works.”

Readers can enjoy the poems in the collection in any order—there isn’t a specific journey that Barry had in mind. “Because I’m also a novelist, if I have any kind of narrative urges that I need to work out, I work that out in my fiction,” she says. When it comes to ordering the poems, Barry says she thinks “in terms or architecture. So, for me, it has to do with poem length. What are the longer poems? Where would I put them in a collection? What would I put in between them?”

The longer poems in the collection are compelling and challenging, and readers can gain more insight by researching some of the poet’s many references to people and places around the world. “In the Family” is a great example of a long poem that explores the coexistence of beauty and horror, a theme that weaves all the way through Auction.

“In the Family” focuses on the elaborate funeral of Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, which the speaker watches online. But alongside beautiful images like “the streets filled with saffron and plum / whole oceans of color,” the poet juxtaposes moments of intense disgust and horror, including a description of a father murdering his son after the child finds photos of his dad wearing a diaper and eating shit.

“It’s a poem that shows how capacious poetry can be—that you can have these radical extremes,” Barry explains.

This dichotomy between beauty and ugliness shines through most beautifully in these lines:

…

Coprophagia. Two blue butterflies so beautiful

their species is named for Adonis,

the insects photographed feeding on a lump of shit.

…

But with “In the Family,” Barry didn’t set out to explore this beauty or ugliness—she was trying to write a poem about shame. Her intuition led her to a different conclusion. “Ultimately it became a poem about community,” she says.

The poem was partially inspired by an experience she had with a Buddhist community on Zoom during the early days of the pandemic. “Basically, it was Zoom-bombed,” Barry says. “Somebody took over the screen and showed a video of a child—just, of terrible things happening to a child.” The disconnect between being in a peaceful Buddhist community space one minute and being transported to a space of violence the next was horrifying. But Barry recognized that even the perpetrators of the Zoom-bombing were, themselves, seeking community. “They’re people who are very disturbed, but even they had a community—supposedly you would get points for Zoom-bombing different kinds of groups,” she says. “I’m sure whoever did this got a lot of points for our group, because it was pretty horrible.”

Though Auction is receiving some buzz—the The New York Times named it one of the best poetry collections of 2023—Barry says she doesn’t put much stock in reviews of her work. “I don’t have any social media presence—I’m not on anything,” she says. “I purposefully cultivate a life in which I don’t know how things are received. I’m at the point where I don’t read my own reviews anymore. Or, if I read them, it’s months and months or years later, where the impact doesn’t feel as immediate.” Though Barry doesn’t internationally theme her poetry books, the toilet sculpture on the cover does suggest a metaphor for the collection as a whole. Yes, toilets represent shit, and most people don’t like looking at them–but this toilet is beautiful. In the same way, the poems inside will hold a reader’s gaze and refuse to let them turn away from moments of shame and violence. Ultimately, Auction will leave readers feeling intrigued and challenged, but willing to see the beauty in life’s ugliness.

We can publish more

“only on Tone Madison” stories —

but only with your support.