Secrets of Science Hall, part three

Sleeping sickness research at UW and its ties to colonialism.

Sleeping sickness research at UW and its ties to colonialism.

This is part three of a three-part series. If you haven’t already, we recommend you read part one and part two first.

By the early decades of the 20th century, scientists had developed the first cure for syphilis, as well as for neurosyphilis, an advanced form of the disease that affected the central nervous system. Salvarsan, developed by the German-Japanese team of Paul Ehrlich and Sahachiro Hata, was the first truly effective drug for treating syphilis. Meanwhile, a team led by Arthur S. Loevenhart at the University of Wisconsin reported that tryparsamide, originally developed at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, was an effective cure for psychiatric patients suffering from neurosyphilis. These two new drugs both contained arsenic, which was also thought to hold some promise as a sleeping sickness cure, as shown by the limited clinical success of another arsenic-based compound, atoxyl.

Bayer 205

A major turning point in sleeping sickness therapy occurred across 1916 and 1917, when scientists at the German Bayer company synthesized an atoxyl derivative called Bayer 205 that was tested with success on sleeping sickness in animals. With their hopes—and patriotism—riding high, the company dubbed the new drug ‘‘Germanin.” When the First World War ended, Bayer supplied the drug to the Hamburg Clinic for Tropical Diseases, where it was tested on several patients who had contracted sleeping sickness in Africa. In one case, after only two injections of Bayer 205, the patient showed recovery.

Staff of the Hamburg Institute for Ship Sicknesses and Diseases of Tropical Countries presented further evidence of the drug’s effectiveness at a professional meeting in Leipzig in 1922. Encouraged by this success, Bayer sent an expedition to Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe) to carry out clinical tests, led by German scientist Friedrich Kleine, who had accompanied Koch on his 1906-07 sleeping sickness expedition to German East Africa. Kleine’s expedition was conducted under the auspices of the British Colonial Office—Rhodesia being part of Britain’s African colonial empire at the time—and was financed by German commercial interests.

Kleine tested Bayer 205 on cattle, monkeys and humans. The first six human subjects included one European and five Africans. All became well, although the European subject reportedly later died from a relapse. By 1923 Kleine had treated almost 250 people and reported that Bayer 205 was “remarkably efficacious.” As reported in an April 18, 1928, article in The Times Of India, he claimed Bayer 205 worked well in cases where “germs had penetrated deep into the central nervous system” although this was later disputed by others. His results were so convincing to the Governor General of the Belgian Congo that he invited Kleine to continue his work in the southern Congo region.

In the 1920s, when Bayer 205 was being developed and tested, colonialism was still very much alive in Africa, but Germany had lost its colonies, which were transferred to Allied powers in the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the First World War. Some German political and industrial leaders wanted to get back into the action. A former District Governor of German East Africa, for example, was quoted in a January 30, 1924, New York Times article as saying that Bayer 205 would make large stretches of tropical Africa suitable for immigration, converting it into a “prosperous, fertile country, inhabited by industrial people.”

Here the story takes a strange turn. Bayer 205 ceased being simply a promising new drug to fight sleeping sickness and instead became a geopolitical weapon. The Bayer company, in alliance with German colonialist advocates, attempted to use Bayer 205 as a bargaining chip to help Germany regain its African colonial empire.

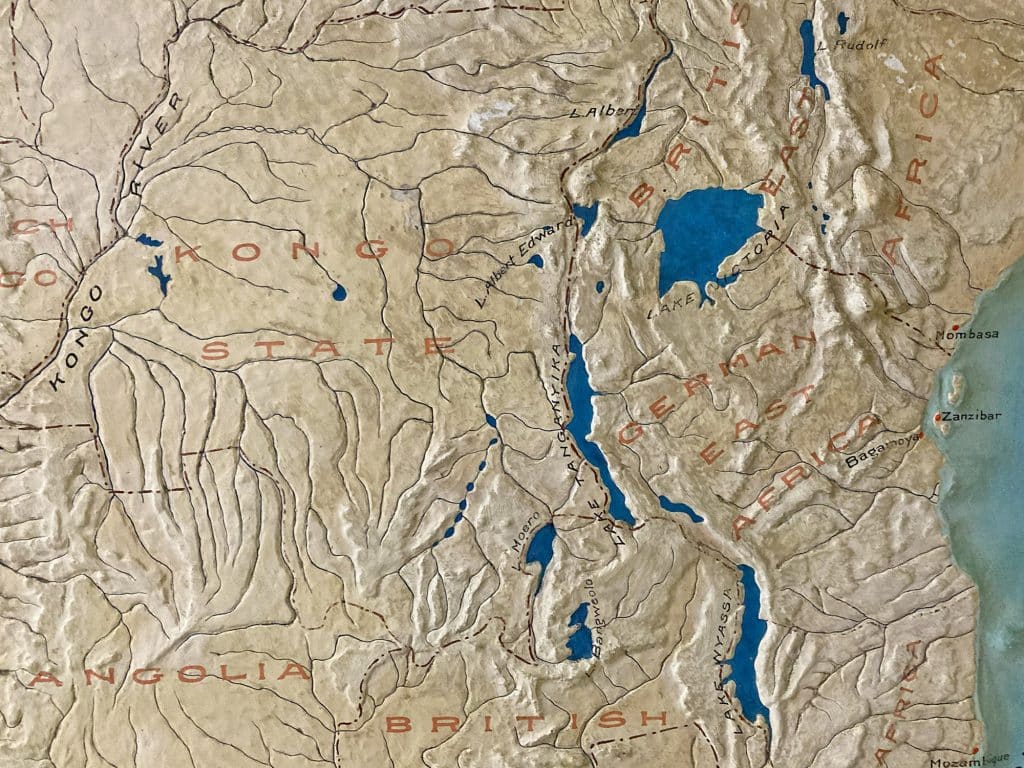

Germany’s African colonies

Germany had been a relative latecomer to European colonization of Africa; its colonial holdings were formalized at the infamous Berlin Conference of 1884–85. These territories included Togoland, Kamerun, and German Southwest Africa—corresponding roughly to the modern nations of Togo, Cameroon, and Namibia—and German East Africa, comprising much of the modern nations of Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi.

The other African colonial powers—Britain, France, Belgium and Portugal—were initially disdainful of Germany’s African possessions, considering them to be, as one commentator put it in a 1916 volume of The Geographical Review, the pieces left over after “all the more promising parts of Africa had already been appropriated.” As it turned out, however, Germany’s colonies were rich in gold and diamonds, and well-suited to industrial-scale agricultural production. When the First World War began in 1914, Germany’s tropical colonies were producing numerous commodities for export, including cotton, sisal, rubber, palm oil and cocoa. With a total area four and a half times the size of Germany itself, the colonies were “a great tropical plantation” ripe for exploitation. European settlement began quickly and by the time of the war several thousand European settlers lived in Germany’s African colonies.

Soon after the outbreak of the war, however, the Allied powers swallowed up most of Germany’s African colonies. Togoland was the first to go, wrested from German control by British and French troops within two weeks of the start of the war. German Southwest Africa was next, surrendered to the British in 1915. The British and French then drove the Germans out of Kamerun (today, Cameroon) in February 1916. Only in German East Africa did fighting linger.

After the war, with Germany’s surrender, the Treaty of Versailles transferred the colonies to the Allied powers. Togoland was transferred to France, Kamerun was divided between France and Britain, and German East Africa was divided between Belgium (modern Rwanda and Burundi) and Britain (modern Tanzania). Several of these former colonies, now under the authority of other European powers, faced periods of violent decolonization and civil war. Most became independent in the 1960s, although South Africa occupied German Southwest Africa until 1990, when the former colony finally gained its independence as Namibia.

Bayer’s bargaining chip

Bayer clearly understood the economic significance of its drug, keeping the formula secret and restricting its supply to a limited number of clinical researchers. British researchers at the Calcutta School of Medicine in India were able to obtain a sample of the drug only under the condition that no report could be published without Bayer’s consent and that no chemical analysis of the drug could be made. According to reports in the The Indian Medical Gazette in 1923, these directives came from “Messrs. Bayer” directly.

In 1924, Sir William J. Pope, professor of chemistry at Cambridge University, stated in an editorial in the British Medical Journal that these actions were intended to serve not only Bayer’s commercial interests, but also the political aspirations of Germany. Bayer allegedly went so far as to offer the formula for Bayer 205 to Britain in exchange for the return of Germany’s lost African territories, but the offer was declined. There is some disagreement about the details of this story, suggesting it may be apocryphal. Some writers allege that both Britain and France were approached, while others argue it was not Bayer that made the overture, but German authorities. In any case, it is not clear that Britain or France alone would have had the authority to revoke the African colonial mandates executed under the Versailles Treaty.

Equally challenging to verify are statements quoted in the newspapers of the day made by unidentified persons. On August 25, 1922, the London Times reported that, at a meeting of the Association of Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Germany, the opinion was expressed that the German Government must safeguard Bayer 205 for Germany alone, its value being so great that “any privilege of a share in it granted to other nations must be made conditional upon the restoration to Germany of her colonial empire.” However, the speaker is not named, making it difficult to assess how seriously this statement might have been taken, or whether the speaker wished to remain anonymous for some reason.

On the other hand, some former members of the German military and colonial establishment were quite willing to make their opinions known publicly. For example, Edouard Achelis, section chairman of the German Colonial Society, a pro-colonial organization, was quoted in the New York Times on January 30, 1924, as stating succinctly, “no colonies, no remedy.” To justify this apparently pitiless attitude Achelis cited British complicity in the death of hundreds of thousands of German civilians in the war through its naval blockade.

Objections to German demands were of course quick to appear. A typical sentiment was that medicine was supposed to be altruistic and great discoveries were to be given freely to the world. Another complaint was that these demands showed German ingratitude, since Britain and Belgium had granted Germany access to research subjects in Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo. The bruised ego of the British medical establishment was on full display. An editorial in the 1922 British Medical Journal stated, “it is a remarkable fact that England should be dependent on Germany for this advance in tropical medicine, for at present Germany has not a single colony, while England has the largest tropical empire in the world.”

Pope (of Cambridge) shared a similar sentiment, citing Germany’s comparative effectiveness in developing a way for scientific researchers to collaborate with industry. Using salvarsan to support his message, Pope urged Britain to ignore the German Bayer 205 ultimatum and develop its own chemotherapeutics for sleeping sickness. He predicted that a few competent chemists could reproduce Bayer 205, or an improved version, within a year. As if to prove his point, in 1924 French scientist Dr. Ernest Fourneau reverse-engineered Bayer 205, patent protection for the drug having been withdrawn from Germany after the war. The French compound, initially called Fourneau 309, was later renamed suramin. Eventually, the Bayer Company confirmed that suramin was identical to Bayer 205.

Bayer’s admission ended any leverage Germany may have possessed to use Bayer 205 for geopolitical ends. Whether real or exaggerated, the idea that Germany had withheld a cure for sleeping sickness in exchange for political concessions caught the attention of researchers around the world. The interest stirred up by the controversy initiated a sort of arms race amongst medical researchers, who imagined beating Germany at its own game by developing alternatives to Bayer 205 that were even more effective.

Warren Stratman-Thomas

At the University of Wisconsin, one of Loevenhart’s graduate students, Warren Kidwell Stratman-Thomas, elevated German duplicity to a new level when he asserted in his 1928 Ph.D dissertation that Bayer 205 was intentionally over-rated to increase Germany’s leverage power. He also avowed that, for treating sleeping sickness, Bayer 205 was no better than salvarsan. A 1928 paper in the Journal Of Pharmacology And Experimental Therapeutics, co-authored by Stratman-Thomas and Loevenhart, stated, “notwithstanding the extravagant claims for this compound, it is the general opinion that in the therapy of South African Sleeping Sickness it is no better than atoxyl.”

Stratman-Thomas was born in Dodgeville, in southwestern Wisconsin, in 1900. He earned four degrees from the University of Wisconsin: a B.A. in 1922, an M.A. in 1924, a Ph.D., in 1926 and an M.D. in 1928. In later life, he would become a renowned malaria research pharmacologist, but in the late 1920s he was entangled in the controversy over Bayer 205. There was of course an element of hyperbole in Stratman-Thomas’ statements. Bayer 205 was in fact the first truly effective treatment for sleeping sickness. Suramin, as Bayer 205 is commonly known today, is one of several drugs still used to treat sleeping sickness in its early stages.

We cannot know for certain the reason behind Stratman-Thomas’ exaggerated statements. Perhaps it was lingering resentment against Germany in the aftermath of the war. Perhaps he simply wanted to discredit Bayer 205 in order to justify his own work with newer compounds. Whatever the cause, for Stratman-Thomas, the race to develop anti-sleeping sickness drugs was not over.

One of the compounds that most interested him was tryparsamide, the drug Lorenz and Loevenhart tested on neurosyphilis patients (covered in part two). Researchers at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, where tryparsamide had first been synthesized in 1915, were testing it on sleeping sickness. After experiments were conducted on mice, rats, and rabbits, the drug was taken to the Belgian Congo in 1920 for tests on humans. This work was led by Louise Pearce, one of the developers of the drug. As the New York Times put it (May 29, 1923)—with a degree of honesty that was probably unintended—“Dr. Louise Pearce went to Africa and experimented with it on the natives.”

A prominent woman medical researcher in the first half of the twentieth century, Pearce earned a bachelor’s degree in physiology from Stanford in 1907 and an M.D. from Johns Hopkins in 1912. She began her career at the Rockefeller Institute in 1913—where tryparsamide was an early success story—and remained there for almost 40 years. Attracted by the idea of doing clinical work in Africa, she volunteered to lead the 1920 expedition, where she studied the effects of tryparsamide on more than seventy patients. She announced the success of the African tests at a conference at the Kennedy School of Missions (now the Hartford International University for Religion and Peace) in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1925. In light of the publicity over the new drug, some newspapers began to call tryparsamide the only known effective cure for sleeping sickness.

Reporters also noted that the discovery of tryparsamide was particularly well-timed given American plans for commercial exploitation of the continent, noting in particular Harvey Firestone’s idea to develop a rubber plantation in Liberia. Firestone, with the approval and support of the U.S. government, was looking for alternate sources of rubber to circumvent the restrictions on supply imposed by British rubber producers in southeast Asia. Since the U.S. did not have any African colonies, it looked instead to nations like Liberia that had not fallen under European control. The nation of Liberia had been founded in 1847 by former U.S. slaves who had been resettled in Africa with the assistance and support of the U.S. government. Surrounded by French and British colonies, Liberia remained among a small minority of independent African states through the colonial period.

In Loevenhart’s laboratory in Science Hall, where Stratman-Thomas worked, the race was on to develop an alternative, not just to Bayer 205, but also to tryparsamide. Despite the effectiveness of the latter drug, Stratman-Thomas and Loevenhart were quick to point out its limitations, including its relative lack of effectiveness for the more acute form of the disease. Like atoxyl, tryparsamide also tended to induce blindness, especially when high doses were administered. This was documented dramatically in a horrifying report from 1930, when a French lieutenant in Cameroon doubled the dose of tryparsamide to speed up recovery of eight hundred patients. Two days later, the patients were all blind.

Stratman-Thomas focused much of his energy testing an assortment of new drugs on rabbits, guinea pigs, mice and rats. Many of these compounds were supplied by other research facilities, but several of them—including etharsanol and proparsanol—were synthesized at the University of Wisconsin. Etharsanol was first prepared by C. S. Hamilton, a researcher in Loevenhart’s laboratory. The Science Hall attic lab also housed samples of live trypanosomes (the microscopic parasites that cause sleeping sickness) from the University of Chicago, the U.S. Bureau of Animal Husbandry, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Rockefeller Institute and the Lister Institute in London.

One wonders what safety protocols were in place at the time. In the 1940 biographical film about Paul Ehrlich, Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet, Robert Koch is shown handing out free samples of tuberculosis bacteria in glass test tubes at his lectures. This is almost certainly Hollywood nonsense, but on the other hand safety standards for hazardous materials were not as stringent as they are today. There are, for example, documented cases where poison gas samples were sent between research institutions via U.S. mail during the First World War, and in some instances the vials broke while in transit.

Stratman-Thomas reported that his animal experiments showed etharsanol to be an “exceedingly effective” drug in the treatment of sleeping sickness in rats and rabbits. Not only that, but in every kind of sleeping sickness infection tested, the chemotherapeutic indices for etharsanol were seen to be better than for tryparsamide. On this evidence, human trials were deemed to be justified and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation awarded Stratman-Thomas a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1928 to study sleeping sickness in the Belgian Congo. According to the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Stratman-Thomas would “determine by clinical trial the therapeutic value of six new arsenical compounds in the chemotherapy of animal and human trypanosomiases.” The initial one-year fellowship was later renewed for an additional year.

Testing in Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) was one of the most notorious and brutal regimes in all of colonial Africa. Under the rule of Belgian King Leopold II from 1885 to 1908, the human rights violations had been so horrific that even the other colonial powers found them extreme. In response to international pressure, the Belgian government annexed the territory in 1908. While conditions improved somewhat after Belgium took control, the main colonial interests were still commercial and little attention was paid to education, healthcare, or alleviation of poverty. The fact that prominent western scientists conducted sleeping sickness experiments in the Belgian Congo—including Kleine (Bayer 205), Pearce (tryparsamide) and now Stratman-Thomas (various arsenicals)—should not necessarily be interpreted as evidence of a deliberate public health effort. As always, commercial motives lay at the heart of colonial administrators’ actions.

Stratman-Thomas sailed on August 2, 1928, for the Belgian Congo with 18,000 doses of six new arsenical drugs furnished by Parke, David, and Company, of Detroit. These six drugs, all developed under the direction of Loevenhart, had been selected from among 139 compounds tested on animals. The drug samples would have included etharsanol, probably proparsanol, and several others. Newspaper articles referred to the drugs by number, rather than name: “Arsenical No 130” and “Drug 115.” The latter may have been the same Drug 115 Stratman-Thomas tested in his dissertation work.

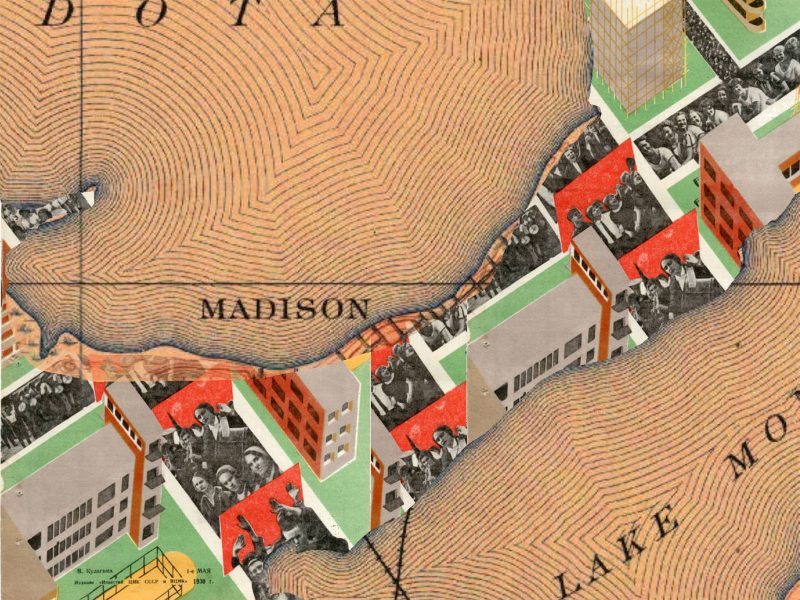

The expedition was expected to take two years. The plan was to test the drugs on “thousands of natives and animals” according to a July 23, 1928, article in the New York Herald Tribune. Stratman-Thomas would establish his headquarters in Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo and work in small villages in the area. Later he was to extend his study into additional areas. The operation was heralded by the New York Times on August 3, 1928, as “the greatest jungle clinic which has been developed in the 200 years that man has been fighting sleeping sickness.” Meanwhile, the Madison Capital Times on April 15, 1929, reflecting the attitudes of the period, printed a story about Stratman-Thomas being stabbed with a spear and living “among tribes that practice the most horrible forms of voodooism and cannibalism.”

How did the average citizen view the effort of western scientists to eradicate sleeping sickness? One innocent New York Times letter writer (July 29, 1928) suggested that these efforts pointed to a “new and most promising type of imperialism through which man will gain empire for all mankind through conquering disease. Nothing is to be traded except good-will and altruism.” Other newspapers made it clear that imperialism would continue to deal in more tangible commodities, citing the beneficial effects on agriculture, economic development and mining.

For their part, Stratman-Thomas and Loevenhart seemed to view their efforts as having both humanitarian and economic benefits. Loevenhart was quoted in The Irish Times on August 27, 1928, calling sleeping sickness a dreadful disease that can “kill off the natives in thousands” and cause them to lose their livelihoods if their domesticated animals are affected. But in a 1926 article in Industrial & Engineering Chemistry he also wrote, “if we can successfully cope with African sleeping sickness, it will considerably increase the surface of the earth available for mankind and would be equivalent to the discovery of a new continent.”

Best-laid schemes

Here Loevenhart’s role in the drama abruptly ended. According to his departmental secretary in a memo dated May 22, 1929, Loevenhart’s health declined significantly in 1928. He had suffered from an ulcer for years and the condition had significantly worsened. In the spring of 1928 Loevenhart was confined to bed for weeks at a time and unable to do much work. Over the summer he was a patient at Wisconsin General Hospital and then went to Europe for further medical aid. In the fall, after returning from Europe, he did no teaching at all and was rarely in his office. In December he had influenza and then was a patient at the Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago. In February 1929 he left for a trip to Florida, where his condition grew worse. He rushed to Baltimore and died there at Johns Hopkins Hospital on April 20 at age 51. He was remembered as an inspiring mentor and possessed a large circle of friends and colleagues. He is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in Madison, next to his wife and two of his daughters who died while still children.

Stratman-Thomas was in Africa when Loevenhart died. While his work there would continue until 1930, the clinical tests he conducted do not appear to have been published. When Stratman-Thomas next appears in the medical research literature he is affiliated with the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Institute studying malaria. His later affiliations include the Station for Malaria Research in Tallahassee, Florida, and the College of Medicine of the University of Tennessee, in Memphis. He is listed posthumously as a co-author on a 1964 paper on malaria in monkeys in the journal Angiology.

The two promising drugs developed at the University of Wisconsin, etharsanol and proparsanol, are mentioned only rarely in the medical research literature after Loevenhart’s death. Research in the Philippines on surra, a form of sleeping sickness in animals, found etharsanol to be essentially useless against the disease. A study on human sleeping sickness concluded that etharsanol and proparsanol were about as effective as tryparsamide but tended to produce visual disturbances. Another study found that etharsanol, like other arsenicals, were not always effective at preventing relapses. Etharsanol and proparsanol were also observed to confer no beneficial effects on neurosyphilis.

Only Loevenhart’s work with tryparsamide for neurosyphilis had enduring value. As noted earlier, the drug continued to be used as a treatment of choice into the 1940s when penicillin came widely available. Research on etharsanol and proparsanol essentially ended when Loevenhart died. No one, it seemed, was positioned to pick up the research and move it forward. This was especially true for Stratman-Thomas, who was employed at the Rockefeller Institute soon after his return from Africa. It seems unlikely that the Institute, having developed tryparsamide and filed its patent, would have been motivated to conduct research on competing drugs developed elsewhere. Stratman-Thomas instead began his work on malaria, possibly as part of a coordinated research program at Rockefeller.

Tryparsamide really did help end the scourge of African sleeping sickness. By 1945, the end of the Second World War, the disease was no longer considered a major public health issue in many parts of the continent, the last major outbreaks occurring in the 1920s. Tryparsamide, often in conjunction with suramin (a.k.a. Bayer 205), was widely used against sleeping sickness until the 1960s, when it was replaced by more effective drugs. But suramin is still on the World Health Organization (WHO) list of essential medicines for first stage sleeping sickness.

According to WHO statistics, sleeping sickness was well under control by the 1960s with less than 5000 cases annually across Africa. The disease rebounded between 1970 and the late 1990s as surveillance relaxed, but following aggressive public health efforts it is again under control, with cases reaching a historic low of less than 1000 annually. Nevertheless, the WHO considers sleeping sickness a neglected tropical disease, a group of conditions that thrive among impoverished communities and disproportionately affect women and children, and as such it is targeted for elimination as a public health problem by 2030. In terms of total incidence and impacts on health, the most important infectious diseases affecting Africa today are malaria—the incidence of which in Africa is orders of magnitude larger than any other region—as well as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis B.

Despite the colonial era’s emphasis on cash crops, Africa as a whole has not become a major exporter of agricultural commodities compared to other regions. Agriculture is an important part of the economy in Africa and provides a livelihood for perhaps three-quarters of the population, but most food is grown for local consumption in what is sometimes called “subsistence” agriculture. According to 2021 statistics from the FAO (the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization) the continent exports less than 4 percent of the world’s agricultural products measured in US dollars. In rubber exports, Africa lags behind other regions, especially southeast Asia, with 14 percent of the world total. Liberia, where Firestone’s rubber plantation got its start in the 1920s, exports less than 10 percent of the continent’s total.

Africa mineral production is a more significant source of exports. The United States Geological Survey’s Mineral Commodity Summaries show that Africa’s mines in 2022 produced about 60 percent of the world’s manganese (used in steel production), one-half of its chromium (used to make stainless steel) and one-sixth of its copper. Also important are precious metals and minerals, including over 80 percent of the world’s platinum, over 60 percent of its industrial diamonds, 50 percent of its gemstones and 14 percent of its gold.

One African country, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (the Belgian Congo in the colonial era), accounts for about 70 percent of world cobalt production. Cobalt is used in the production of rechargeable lithium batteries to feed the growing market for electric vehicles and portable electronic devices. As such, lithium and cobalt supply security has become a top priority for technology companies worldwide in recent years.

However, the cobalt mining industry in the Congo has come under severe criticism for its labor practices, which include the use of child labor and slave-like conditions. Harvard’s Siddharth Kara, author of the book Cobalt Red, described it as “a horror show” from a different century in a National Public Radio story from February 1, 2023. The mining operations also exert a ravaging effect on the environment including deforestation, air pollution and water contamination. In some ways it seems things have not changed all that much since the colonial era. One wonders how we will look back on our complicity in these practices a hundred years from now.

Africa’s colonial legacy continues to be a stumbling block to the establishment of strong national economies and regional trade networks in Africa. The continent is still reckoning with decisions made by colonial governments 100 years ago. However, colonial administrators in the early 20th century did get one thing right: they understood that infectious disease had a detrimental effect on economic development. As researcher Yahyaoui Ismahene shows in a 2022 article in the Journal Of The Knowledge Economy, higher disease incidence is almost always negatively correlated with economic activity, since poor health has a deleterious effect on labor productivity, family income, educational attainment, investor risk perceptions, and other factors. Improving healthcare is not only compassionate, but also good economic policy.

In the colonial era, unfortunately, the economic benefits of disease management were one-sided, serving only the interests of European capital and a small number of African elites. Commercial exploitation of the continent was highly dependent on local labor, already in short supply, which made elimination of disease a critical priority to colonial administrators and their industrial allies. The objective was to ensure a steady supply of productive manual labor—including forced labor—to sustain mining and agricultural operations. This helped justify the clumsy and careless medical practices adopted in Africa at the time.

Back in the attic of Science Hall, dust collects on the shelves that once held medical supplies and cages of rabbits and rats. No one comes to look at the dilapidated space or try to imagine what the room looked like one hundred years ago when Loevenhart and his students and colleagues were regular visitors. Everything of value, from the laboratory cabinet tops—possibly made of black soapstone—to the Kohler sinks, has been removed. The pigeons have the floor all to themselves. While the room looks dilapidated today, the activities that took place here in the 1920s under the guidance of Arthur Loevenhart had impacts that extended far beyond the boundaries of Science Hall, the university and the state. Science Hall’s association with the medical school imprinted the building with a complex and nuanced history that embodies the record of early 20th-century medical research and its far-reaching influences.

Readers who would like a copy of the article with all bibliographic references should contact the author at h.veregin@gmail.com.”

Who has power in Madison,

and what are they doing with it?

Help us create fiercely independent politics coverage that tracks power and policy.